TEXT BY 撰文 x QIWEN KE 柯淇雯

TRANSLATED BY 翻譯 X BOWEN LI 李博文

Compared with the well-known Dadaism, Futurism, Surrealism – the art movement Fluxus, as obscure as it was, probably owns its fame chiefly to Joseph Beuys.

In the previous decades, the definition of the Fluxus was already difficult enough a problem for the followers and the historians. And, time only proves that all efforts have been in vain. There are at least four reasons for this: firstly, Fluxus is not an organization. Besides the fact that those affiliated with the movement were scattered around the globe, they were also not interested in the idea of having a clearly structured organization. Secondly, there was no single manifesto – there was at least five. George Maciunas, recognized as the founder of the Fluxus movement, presented at least five manifestos from 1961 to 1966, but everybody else were not satisfied and had reservations. There was no unified style – this is rather easy to understand, as one of its slogans was “freedom、personality、experimentalism”. Lastly, Fluxus in this way inherited and refreshed the essence of pre-war Avant-garde – anti-art,anti-art sensibility,anti-establishment, anti-commercialism,anti-institutional. No wonder really, it is really hard to start a conversation about it today.

In this way, it also renders arguments about it rather meaningless. As Robert Watts has it:“The best thing about Fluxus is that nobody knows what it is.”Perhaps undefinability is one of its biggest feats.

The Strange Origin of the Fluxus

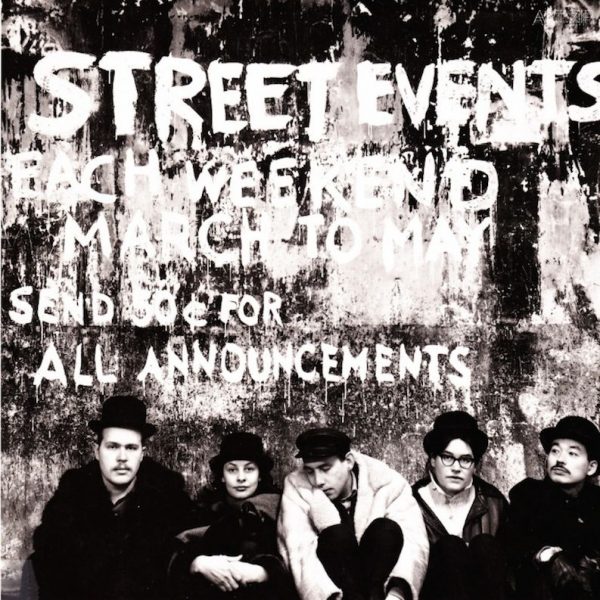

The term fluxus finds its root in Latin: flow, flux, flowing, fluid. Fluxus as it is known today was first used as the title of a cultural magazine, published by Maciunas and friends in New York in 1960. Due to differences in political views among the publishers they stopped the magazine. After this, Maciunas’ AG Gallery had only a very short life as well. Fleeing from his debts, Maciunas went back to the continent in 1961. Inspired by the new atmosphere of the art scene there Maciunas wanted to pick up again the magazine business. In the year of 1962, Maciunas produced a music festival under the same name as a fundraising and promotion event for the magazine that was to come.

Unconscious Absurd

A certain Fluxus spirit was present as early as in the 60s – artists and intellectuals scattered around the world were unconsciously or rather aimlessly creating works or experimenting by themselves, discontinuously. The most influential one among them was of course the great John Cage and his Experimental Composition course, who exerted immense influences on Dick Higgins, George Brecht, Al Hansen among many others. Only when the Fluxus music festival took place did the members realized that they were not alone and were in fact practicing in the spirit of Fluxus.Since then, they become known as the Fluxus-people, and started working actively in the art world.

Conscious Absurd

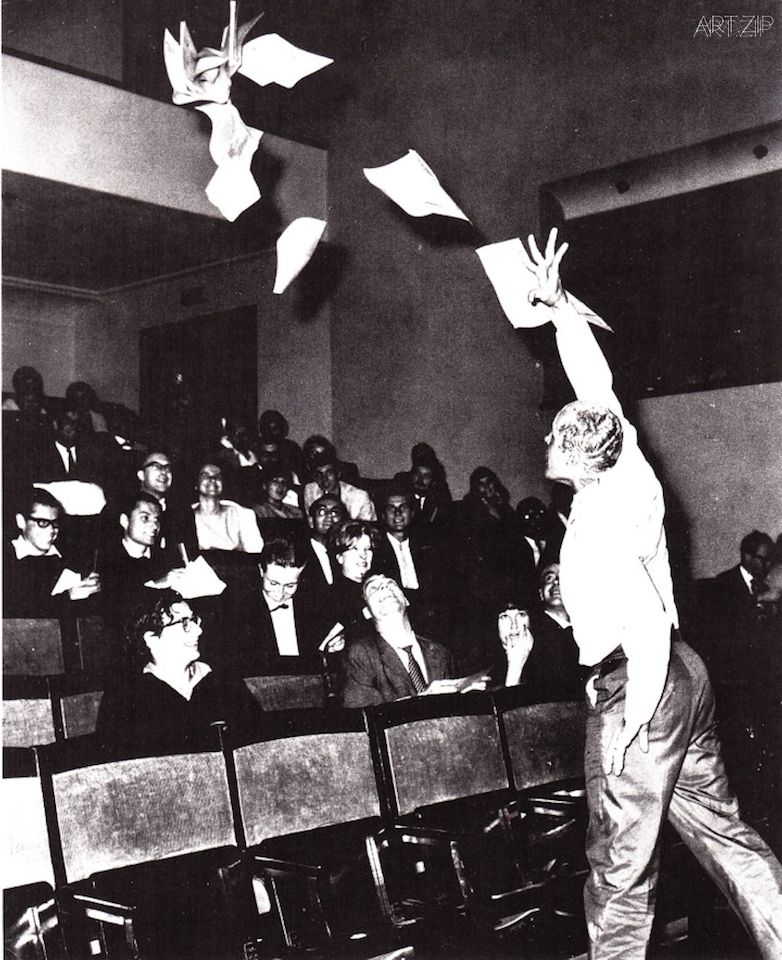

With the first music festival undergoing in 1962, the founder Maciunas, without knowing clearly what could define the Fluxus, claimed: “Let’s Fluxus!” Artists following this rather absurd figure started a series of eccentric, unconventional acts, known also as the Neo-Dada.

Monumental Event as the Biggest Scandal?

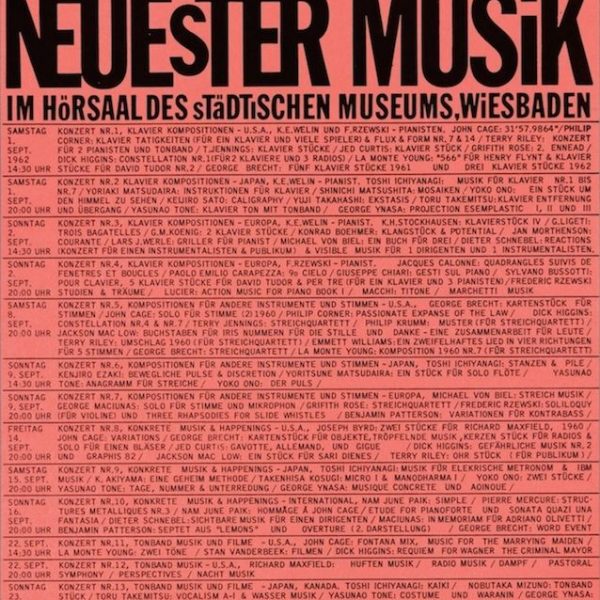

In 1962, the four-weeks long The Fluxus International Festival of Very New Music took place in the Wiesbaden Museum. This was the grand opening of the Fluxus, but it already irritated a number of artists and medias because it was prepared only in a short time and was not well-organized. But the biggest scandal was Philip Corner’s Piano Activities(1962). Corner was not there, to be sure; Maciunas and three other artists, furious about the financial shortage, abused the grand piano with equipments and tools found on-site. They did not stop the impossible improvisation until the piano was shattered to pieces. This event was considered by the German as a violence against the favourite instrument of Chopin, and immensely agitated the audience.

The impact of the event was, however, surprisingly phenomenal. This music festival kicked off the whole traditional event, and brought New Music to its height. Through activities as such Fluxus promptly spread in the whole of Europe.

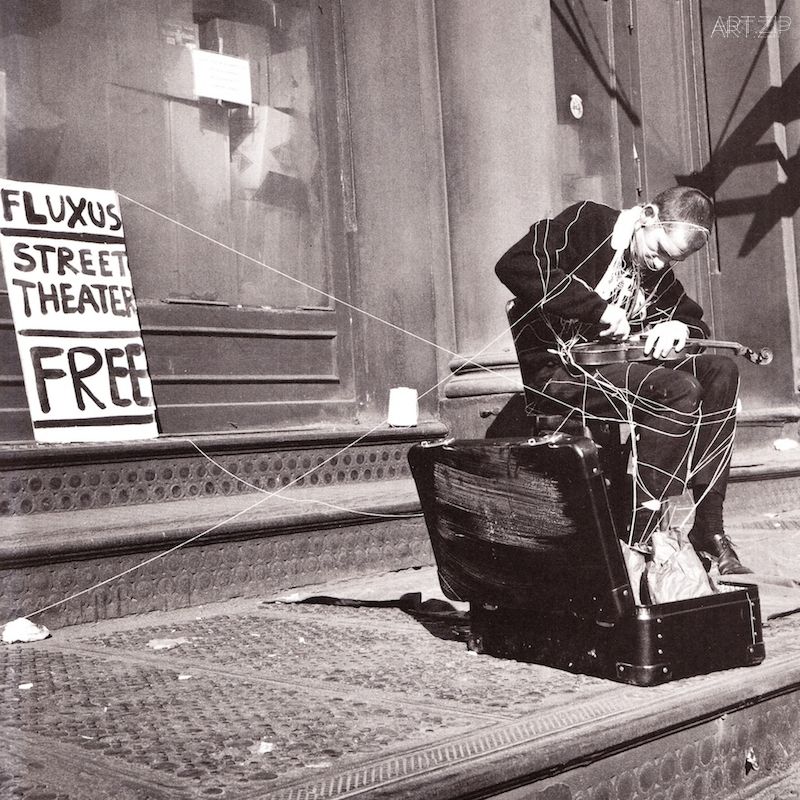

Omnipresent Fluxus

Fluxus is not: a movement, a moment in history, an organization. Fluxus is: an idea, a kind of work, a tendency, a way of life, a changing set of people who do Fluxworks.–Dick Higgins

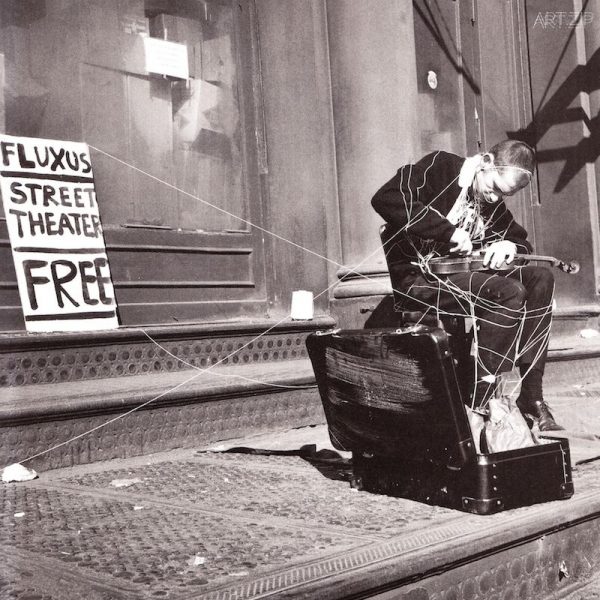

Robert Watts said that there were Fluxus wherever he went, whatever he saw. Fluxus was like a web, connecting all – painters, sculptors, musicians, authors, architects – a great number of them fell in voluntarily, but a greater number of them oscillated in and out.

“Anything can be art and anyone can do it”—George Maciunas

Fluxus blurred the boundary between life and art, and that between the artist and the spectator. Regarding artistic creation, Fluxus encouraged simplicity, humor, anti-mannerism, focused on the work itself, and did not care for techniques and unlimited associations. This fundamentally freed art from its pedestal and encouraged participation of all.

Smart Fluxus

George Maciunas was considered the founder of the Fluxus. He also opened the Fluxus shop through which art became subject to massive productions, and was no longer a toy of the upper class.

John Cage was an influential experimental musician, and was considered the father of the Fluxus. Experimental music broke all set limits, with the 4’33”(1952) as its example par excellence. The performance of 4’33” did not involve a single note, and the audience has to feel four and half minutes of silence in which his/her own sound and the environment are brought to the foreground. Cage’s philosophy had it that the nature of music is not performance but the act of listening.

George Brecht was an American conceptual artist, composer and chemist. He invented the Event Score and started spreading art in the form of mail art.

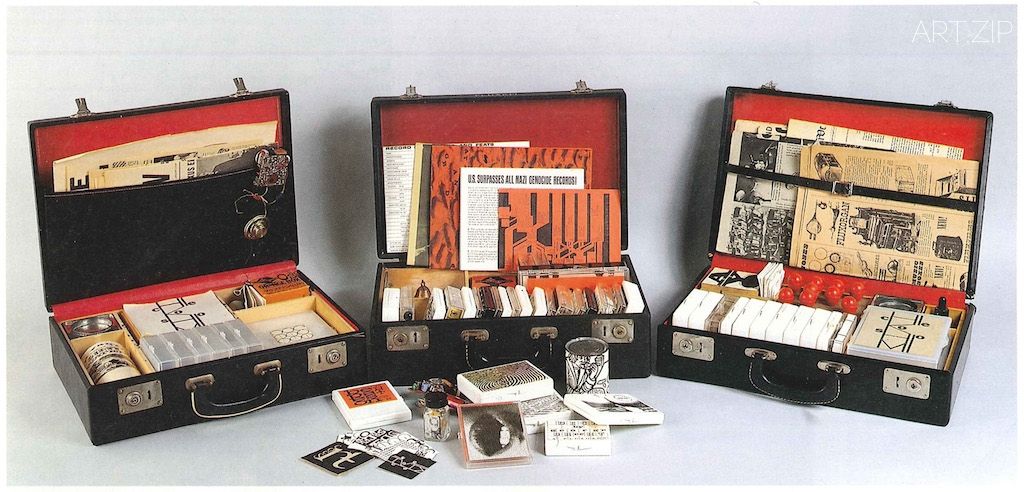

Marcel Duchamp was also considered a Fluxus-people. As an avant-garde artist, his Boîte-en-valise (1935-41) gave birth to another art form of Fluxus: Fluxbox. Fluxbox and Event Score were the two most popular form of Fluxus art.

Dick Higgins came up with the term Intermediate Art. In the spirit of the Fluxus, Higgins promoted the idea of an art form that breaks the boundary between music, performance, visual art, and literature.

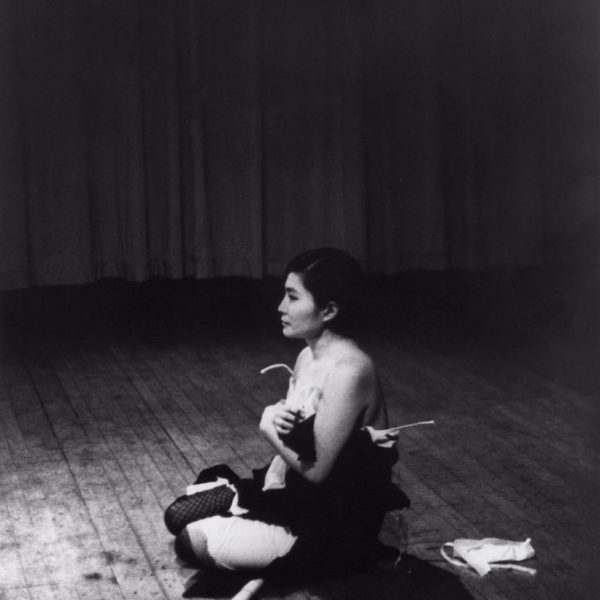

Other representatives include Ay-O, Allan Kaprow, Al Hansen, Alison Knowles, Joseph Beuys, La Monte Young, Nam June Paik, Yoko Ono among many others.

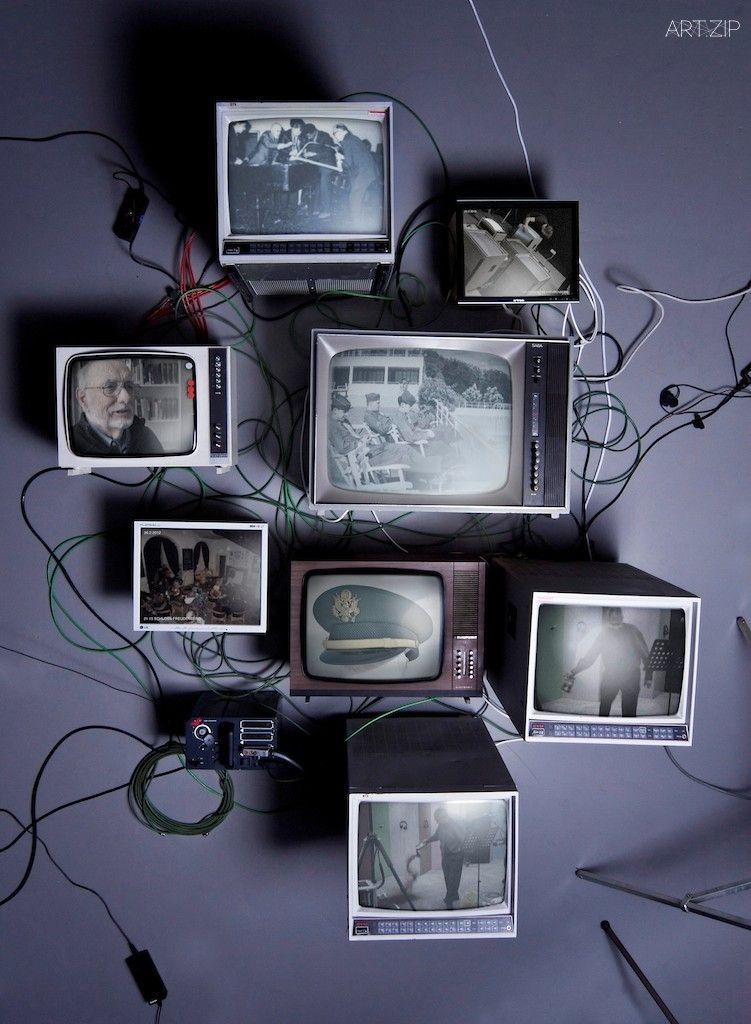

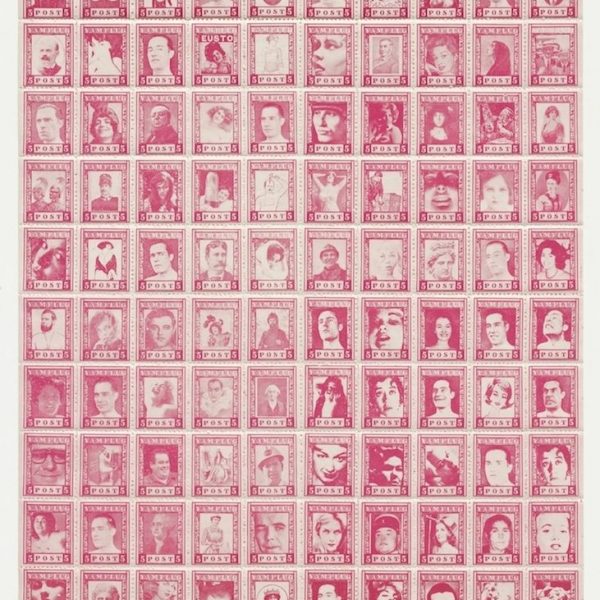

- Watts, Robert

- Originalprogramm

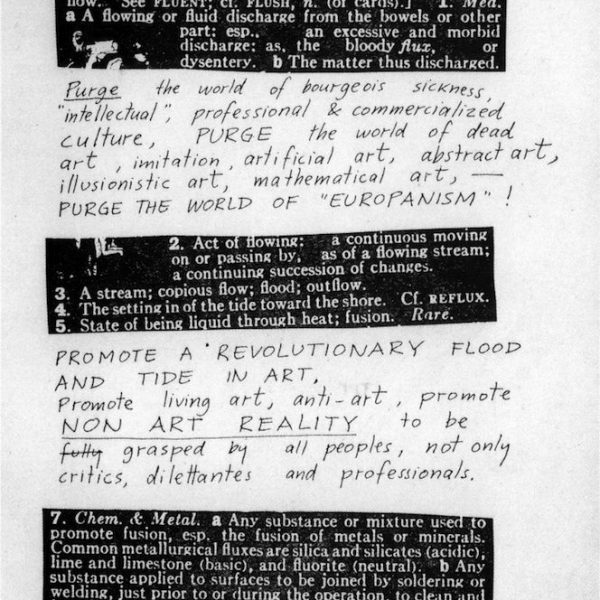

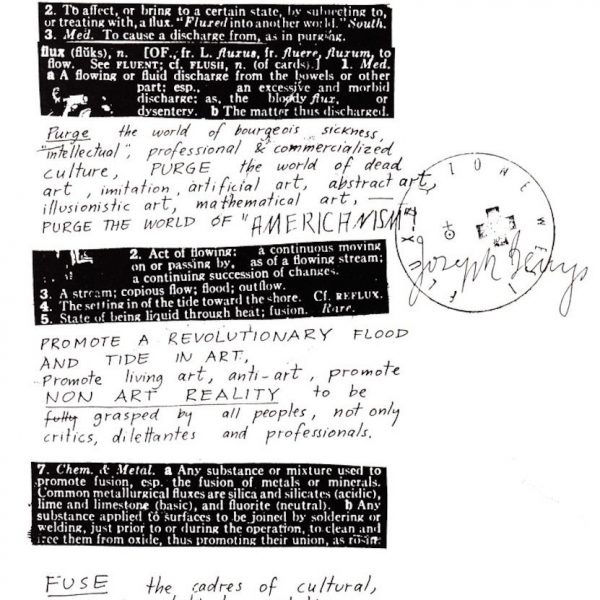

- Fluxus Manifesto

- Fluxus

A Cat and Mouse Game?

Thanks to its denial of traditional institutions, this avant-garde, revolutionary movement of art started in the 1960s has always been on the border between the mainstream and its outside. Firstly, in its attitude, it despised the high art – Maciunas argued for the non-commercialization of art in his manifestos. Secondly, Fluxus art was chiefly in the form of performance, sketching or readymade, and was therefore in fact not of inherent commercial value then. The early Fluxus artworks were mostly anonymous or very much private; only a handful of collectors devoted their time and money to support this unlikely art movement.

Beuys was not very much directly involved in the formation of the Fluxus. Shared with the major Fluxus movement the slogan “Everyone is an artist”, Fluxus was fighting against art, against institutions, while Beuys infiltrated deep into the system. Without Beuys, Fluxus perhaps would not be as influential a strange movement of art.

As the Fluxus was becoming evermore powerful, an irreconcilable break happened from the inside. The Fluxus had secured its position in history, but, ironically, for the safe placement of the art and its exhibitions, they had to come back to institutions and to observe the rules. After five decades, though the movement has yet completely fulfil its original goal, its spirit still drives and inspires the younger generations.

上世紀的藝術圈內,若“達達主義(Dadaism)”、“未來主義(Futurism)”、“超現實主義(Surrealism)”是耳熟能詳的名詞,那略顯生澀的“激浪派”似乎是因為沾了約瑟夫·博伊斯(Joseph Beuys)的光,才逐漸被藝術機構及公眾所聽聞及認同。

在過去幾十年裡,“定義‘激浪派’”一直是激浪者們熱議的頭號難題,然而時間證明了一切都只是徒勞而已。論理據,大致可以從四個層面分析:首先它不存在組織一說,且不提激浪者們分布松散的外因,他們對歸屬組織或流派的行為是排斥的;其次,激浪派沒有統一宣言。盡管激浪創始人喬治·麥素納斯(George Maciunas)在1961-1966年期間先後草擬了五份宣言但激浪者們均持保留態度;也沒有統一風格——這並不難理解,統一也就違背了其口號“自由、個性、實驗主義”;最後,激浪派繼承和刷新了戰前先鋒藝術的精髓——反藝術、反規律、反理性、反常規,所以要自立門戶、成为一个独立的艺术流派是相當困難的。

這樣看來,爭論的确是无意义的。正應了羅伯特·沃茨(Robert Watts)的話:“沒有人知道激浪派到底是什麽,也許它本就該這樣子。” 換個角度想,“無法定義”也正是激浪派的一大特色!

“激浪派”的荒誕由來

“fluxus”一詞源於拉丁語,意思是流動的、無常的、搖擺的。“fluxus”最早用於一本文化類雜誌名稱《激浪派》,這是1960年麥素納斯和好友在紐約創辦的。後因政治分歧停止出版,隨後成立的AG畫廊也因經濟不景氣而終止運營。1961年為了躲避債務麥素納斯逃回歐洲,全新的藝術氛圍讓他重燃了出版刊物的夢想,基於提升雜誌知名度和募集資金的需要,1962年同名音樂節應運而生。

無意識荒誕

其實激浪精神早在20世紀60年代就出現了,只是當時散落世界各地的成員們無意識或無目的地進行著單獨、不連續的創作實驗。其中影響最為深遠的當屬被一部分成员视作精神教父的約翰·凱奇(John Cage)的“實驗音樂(Experimental Composition)”課程,這為當時紐約先鋒派藝術家如迪克·希金斯(Dick Higgins)、喬治·布萊希特(George Brecht)、艾爾·漢森(Al Hansen)等人帶來了曙光。直到激浪音樂節的正式聚首,成員們才紛紛意識到過去幾年的藝術活動屬於激浪的範疇,也是從那時起他們開始被稱作“激浪者(Fluxus-people)”,並以激浪為標誌繼續活躍在藝術舞臺。

有意識荒誕

1962年首屆音樂節已經在如火如荼地進行中,在創始人麥素納斯尚不明確激浪派的概念時,他毅然高調宣布:“讓激浪派成立吧!”在這個荒誕創始人的號召下藝術家們開始了一系列離經叛道的行為,也可以理解為“新達達Neo-Dada”。

里程碑事件是最大的醜聞?

1962年在德國威斯巴登博物館(Wiesbaden Museum)舉行了為期四周的“激浪·國際最新音樂節(The Fluxus International Festival of Very New Music)”。這是激浪派的開端,盡管籌備倉促引起了部分藝術家與媒體的不滿,但菲利普·科納(Philip Corner)作品“鋼琴行動(Piano Activities,1962)”確是城中最大的醜聞。當時表演者科納並未到場,事件起因是運輸經費的短缺,以麥素納斯為首的四位著名藝術家利用在場工具對那架三角鋼琴大肆發泄,各種即興的節奏合成樂曲,直到整架鋼琴被摧毀殆盡。這次“偶發事件”在德國人眼裏是褻瀆了肖邦摯愛的樂器,同時也引起了在場觀眾的陣陣騷動。

但這些出格之舉的影響力卻是出乎意料的。這次音樂會吹響了反傳統的號角,將“新音樂New Music”推至風口浪尖。憑借著此等破壞行徑,激浪派迅速向全歐洲乃至全球蔓延開來。

無孔不入的激浪精神

“激浪不是:一運動、一歷史性時刻、一組織;激浪是:一觀念、一作品、一趨勢、一生活、一變化的激浪者。“——迪克·希金斯

羅伯特·沃茨也曾說過他所見、所聞之處都是激浪。激浪就像是一張網,網羅了全世界,也網羅了各路人馬,有畫家、雕塑家、音樂家、作家、建築師等。在隨後的日子裡不斷有人自投羅網,也有人偏愛在網邊遊徊。

當然蠱惑人心的“愚民政策”絕對功不可沒——“人人都是藝術家”;拒絕“高雅藝術”走進“平凡藝術”;“生活即是藝術”等標語勾勒出一幅藍圖,它模糊了生活和藝術,藝術家和觀眾的界限。對於藝術創作,激浪派主張簡易、有趣、不矯飾、注重作品本身、不需要技巧及無止境的聯系,這又從根本上降低了藝術的門檻,倡導全民參與。

手段高明的激浪者

喬治·麥素納斯(George Maciunas),激浪派創始人,創辦激浪商店使藝術品量產化,使得藝術不再只是上流社會的玩物。

約翰·凱奇(John Cage),美國著名實驗音樂作品家,被視作激浪精神之父。“實驗音樂”打破了一切既定的音樂法則,其代表作《4′33″(1952)》沒有任何音符,演奏會受現場環境與觀眾行為影響,觀眾從四分半的寂靜中去感受一切。他的哲學觀點是音樂的本質不是演奏而是聆聽。

喬治·布萊希特(George Brecht),美國觀念藝術家、作曲家、化學家。他發明了一種藝術形式“事件樂譜Event Score”並以郵寄藝術(mail art)的方式廣泛傳播。

馬塞爾·杜尚(Marcel Duchamp),“實驗藝術”先驅,他的作品《手提箱裡的盒子(Boîte-en-valise, 1935-41)》催生了另一種激浪藝術形式“激浪盒子Fluxbox”。“激浪盒子“和“事件樂譜”是激浪者最常采用的攜帶或郵寄作品形式。

迪克·希金斯(Dick Higgins),杜撰了新詞“中介藝術(intermediate art)”。激浪派倡導打破音樂、表演、視覺藝術、文學等各領域的界限,形成跨媒體的綜合性藝術。

另外積極發揚激浪精神的代表人物還有Ay-O、艾倫·卡普羅(Allan Kaprow)、艾爾·漢森(Al Hansen)、艾莉森·諾爾斯(Alison Knowles)、約瑟夫·博伊斯(Joseph Beuys)、拉蒙特·揚(La Monte Young)、白南準(NamJune Paik)、小野洋子(Yoko Ono)等。

一場貓和老鼠的遊戲?

這場盛行於1960年代的先鋒藝術革命一直迂迴在主流藝術以外。主要原因是它摒棄了最直接的門檻——傳統藝術機構。首先,在態度上,它拒絕高墻內的藝術,麥素納斯在他的宣言中也主張藝術的非商業化;其次激浪藝術主要由行為表演、草圖或者現成品構成,在當時並不具備商業和收藏價值。所以早期的激浪藝術作品是以匿名和私人的方式存在,只有少數私人藏家願意花時間和金錢去支持激浪藝術。

文章開頭提及了激浪派重要代表約瑟夫·博伊斯,他是分離在激浪派之外的一位特殊人物。同樣打著“人人都是藝術家”的旗號,激浪派在進行反藝術、反機制的獨立活動,而他卻是深入藝術機制內部的。盡管與激浪派理念相違背,但是不可否認因為博伊斯的影響力世界漸漸認識激浪派,並開始認真審視這門“不入流”的藝術。

文章開頭提及了激浪派重要代表約瑟夫·博伊斯,他是分離在激浪派之外的一位特殊人物。同樣打著“人人都是藝術家”的旗號,激浪派在進行反藝術、反機制的獨立活動,而他卻是深入藝術機制內部的。盡管與激浪派理念相違背,但是不可否認因為博伊斯的影響力世界漸漸認識激浪派,並開始認真審視這門“不入流”的藝術。

隨著激浪派影響力的加深,內部開始察覺到一個不可調和的矛盾。激浪藝術已經成為上世紀60年代不可或缺的代表,諷刺的是,若出於對作品妥善保存和系統展示的考量,他們似乎不得不回歸到藝術機構中,繼續遵循牆內的遊戲規則。如今激浪派已走過半個世紀,雖然沒有完全達成最初的理想,但它的精神持續激勵著後代朝這個目標前行⋯⋯

Quotation:

“Purge the world of bourgeoisie sickness, “intellectual,” professional and commercialized culture, purge the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic art, mathematical art, – PURGE THE WORLD OF “EUROPANISM!” PROMOTE A REVOLUTIONARY FLOOD AND TIDE IN ART, promote living art, anti-art, promote NON ART REALITY to be fully grasped by all peoples, not only critics, dilettantes and professionals.”

– George Maciunas, from the Fluxus Manifesto