TEXT BY 撰文 x SHAHEEN MERALI 莎壬·莫拉裏

TRANSLATED BY 翻譯 x BOWEN LI 李博文

In many cases artists whose practice is predominantly performance based, are recognised by the autobiographical tone of their work. Using identity as a primary credential, this article will address the consequence and expectations in terms of how certain performance artists are often framed, marketed and dramatically characterised within the wider discourse; a path that

The term artworld itself is one coined by the presently disillusioned and yet influential art critic, Arthur Danto, “Danto’s definition has been glossed as follows: something is a work of art if and only if (i) it has a subject (ii) about which it projects some attitude or point of view (has a style) (iii) by means of rhetorical ellipsis (usually metaphorical) which ellipsis engages audience participation in filling in what is missing, and (iv) where the work in question and the interpretations thereof require an art historical context.” It has been argued as to how clause iv) makes the definition institutional.leads some to a form of self-curation and a way of making themselves visible in the artworld.

In mining this definition further towards the subject of artists as curators, one has to ask a more general question; which artists are termed Performance artists or should they known as ‘artists who perform’?

I would argue that one of the key ways a number of these artists are institutionalised is by an autobiographical appendix that remains indexically linked to the way their work is presented, received and historised. So all of the above clauses including the distinct one of an autobiographic reading are applicable to artists but specifically to performance artists.

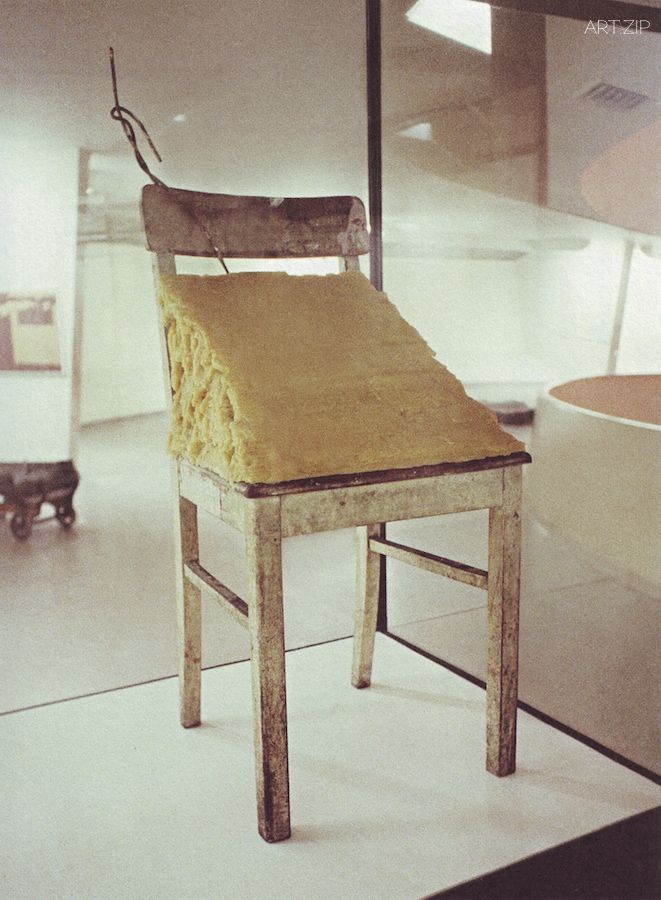

One of the prime examples of such an autobiographical tagging would include the passionate German artist Joseph Beuys, who in 1941, volunteered for the Luftwaffe. He began his military training as an aircraft radio operator in 1941 and the perennial bind of surviving a plane crash and on rescue being wrapped in fat and felt to keep him alive remained deeply ingrained.

He wrote, “Yet, it was they (the Tartars) who discovered me in the snow after the crash, when the German search parties had given up. I was still unconscious then and only came round completely after twelve days or so, and by then I was back in a German field hospital. So the memories I have of that time are images that penetrated my consciousness. The last thing I remember was that it was too late to jump, too late for the parachutes to open. That must have been a couple of seconds before hitting the ground. Luckily I was not strapped in – I always preferred free movement to safety belts… My friend was strapped in and he was atomized on impact – there was almost nothing to be found of him afterwards. But I must have shot through the windscreen as it flew back at the same speed as the plane hit the ground and that saved me, though I had bad skull and jaw injuries. Then the tail flipped over and I was completely buried in the snow. That’s how the Tartars found me days later. I remember voices saying ‘Voda’ (Water), then the felt of their tents, and the dense pungent smell of cheese, fat and milk. They covered my body in fat to help it regenerate warmth, and wrapped it in felt as an insulator to keep warmth in.”

It is not inconsistent with Beuys’ work that his biography would have been subject to his own reinterpretation; this particular story has served as a powerful myth of origins for Beuys’ artistic identity, as well as providing the interpretive key to his use of unconventional materials, amongst which felt and fat were central to an array of acrimonious public acts.

The above encounters led Beuys to resolve his dilemma by modes of autonomous representation, in a repatriation of knowledge and organisation. Beuys subsequently founded the German Student Party, the Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research and in 1976 ran for the German Bundestag (parliament). In mapping a legacy where avant garde materials and methods are used in art, the autobiographical and self governance become a necessary portal to a successful confrontation to and with the conservative ideological artworld.

The autobiographical presence for artists who are committed to performance or an avant garde trajectory is, I would like to suggest, a necessary strategy as an act of renewal of democracy.

A second form of artistic-led mobility towards presence is evident in the generation that followed Beuys; decades which saw the formation of groups rather than associations, collectives and cooperatives rather than an International coalition around ideas.

One of the most important was the Black Mountain College, from which a narrative or causal relation to each other as interdisciplinary artists, provided a collective marking. Dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham and composer and musician John Cage emerged alongside Robert Rauschenberg and Buckminster Fuller. A student of John Cage, Allan Kaprow, later termed and held the first happening. It is impossible to condense the work at Black Mountain College, or Cage and Cunningham’s extensive and influential careers, experimental by nature and committed to a multifaceted approach. The college attracted a faculty that included many of America’s leading visual artists, composers, poets, and designers, whose interest was in an allowance for complexity including that “committed to democratic governance and to the idea that the arts are central to the experience of learning.”

In an artworld where there is no logical certainty, judgments, whether aesthetic or concerning how to evolve in a market or institutional practice are not clearly provable.

Having said that, in my position as a curator and in my conversations with artists, it is possible to evaluate the potential that they have been able to source, including the historical legacies of autobiographical tagging and in the formation of groups. The latter have certainly provided cohesive steps towards a form of recognition that accommodates their practice to be embedded into funding and exhibiting structures. Frameworks, as well as collective networking, allow for the distribution of ideas and address the goal for visibility and continuity.

Since the times of Beuys and the Black Mountain College, we find ourselves living and working in increasingly expensive cities with rental arrangements gradually becoming unmanageable; combined with art and luxury cohabitation, the control of art has to a large extent reversed within its stakeholders, resulting in art practitioners. Its producers are in competition with the art industry whose disproportional use of its prowess has disturbed the course of trust, good will, generosity and a great deal of other traditional factors, including philanthropy and patronage, access to media, and the entry to both private and state collections.

In so many cases it is the gallerist or its assistants who mediate many of the relationships and it is in this broken interpersonal relationship that ideas have gradually been replaced by an economy of signs. We continue to look for security in our relationships, although it is increasingly obvious that our models for that area of life are also not matching up with reality very well.

From a curatorial perspective what has been interesting to note down are the following modes of presenting ideas and operating in this contemporary setting that allow for the artist to recover their pace of development but, even more importantly, preserve a sense of independence both as producers and amongst those actively involved in its curatorship.

I state the following trends by implying that these fragile relationships have meant that artists who are involved in marginalised practices, including performance work, digital and ephemeral artists or even those involved in art as protest, have had to accept change in the last two decades and to incorporate self organisation as a working reality. Often they find themselves outside institutional curators’ and collectors’ radars.

The first of the two changes is in the rise and use of lectures and essays by artists; a foreshortening that stems from the nineties production of ethical frontiers between art theory and practice. I refer here to artists who see themselves in a performing context, a mode not necessary considered as such by organisations who initiated performance or live art from the 70s, 80s and even the 90s.

Prime practioners of the essay performers include, Hito Steyerl, Harun Farocki, Liam Gillick and Rabih Mroue- all present cautionary tales approximating a social consciousness from a global perspective, dovetailed to the culture of anxiety.

A relevant factor to consider in terms of the market and the institutional support that initiates curated exhibitions, is that these artists’ practice emerged in correlation and association with the pioneering e flux, email subscription service. E flux’s ever increasing meta database and progressive experimental ideas, a thrust from e flux’s editorial board as a professional promotional agency for global institutions, has effectively provided a series of opportunities and settings for a group of artists; linking data and potentials which have for these critical writers, speakers, performers and video based artists been important. Initially a number of analogous artists were presented through e flux’s journals and conferences and progressively created access for curating institutional exhibitions, followed by their work in compatible collections, resulting in successful ventures into the commercial market.

Such a contemporary model based on a campus of assembled intellectuals working with a directed agenda, was the domain of endowment institutions including the Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts or the Getty Foundation but has rapidly been devolved to art publications including the proposed art education facility to be established by frieze magazine.

As a conclusion to this first wave of associative practices, perspectives and art services inclusive of the market and curating have been highly effective in productively linking data to an emerging philosophical rim. To this extent, it has shaped a network for a large group of artists who are regularly programmed by related museums and institutions and teach on predominantly curatorial courses throughout the world; a framing of discourse that finds itself made relevant and has even emerged in the market.

A second and lesser emerging platform is once more related to discourses with an emphasis on geographies rather than to political address, as such designated as expanding narratives. The content is articulated and reflective of fictional and non-fictional places, achieved through performative lectures, installations and collectable publications, embraced in the work of Simon Fujiwara and Slavs & Tartars.

These artists rely on commissions by sympathetic foundations, biennales, art fairs and concurrently work with commercial galleries. Their work is collected in the form of objects, videos but, more importantly, the process allows them to realise their ideas on multiple, including self curatorial, platforms from which the relics as publications, objects, video or documentary material are released as commercial stock.

In the former times presenting research as a strategy for artistic practice, had remained the sole domain of research funding from higher education institutions, as it is often a precarious and beguiling balance based on strategic re-formulation; Slavs’ and Tartars’ regional linguistic web-like encasing or Simon Fujiwara’s intriguing journeys involving gumshoe archeology, travel and sexuality are dependent on revealing specific correlations; their instigations have won over funders willing to stay the course, a condition that allows a great deal of curatorial independence.

The fascinating absorption in the artists’ process alongside the empowering of difficult projects has played an interesting role for the funders who often contribute as co-producers; a role that came to the fore in the undertaking of the ambitious Cremaster Cycles spurred by the performance work of Matthew Barney, a testament to artists’ films as major film works. The Cremaster Cycle was produced as films by his New York gallerist, Barbara Gladstone and is viewed as a tour de force for the curatorial ambition of an artist and an achievement in terms of tackling a difficult and industrialised genre.

It is fast becoming obvious that artists who preside as an authority over unrestrained assembling are operating in this definitive mode. Ryan Trecartin’s, co-curation of the New Museum Triennale, Surround Audience (2015) provides a generational setting that “grapples with this sense of multiple realities, or at least the idea that the digital has diced and sliced the ways in which we experience the world.” The presence of Trecartin’s work at the Venice Biennale and major commissions at KunstWerk, Berlin and Zabludowicz Collection, London amongst others, has permitted inserting his sense of a community of interlocutors including the New York based Dis Collective as the forthcoming curators of the Berlin Biennale (2016).

Finally, I would suggest that the recent presence of the artists’ collective has enforced a sense of production by self- determination, a battle against hegemonic invisibility and powerlessness.

Many collectives have successfully ventured into the curatorial realm and their presence has been incrementally persuasive in the arts. Some of the choices they have made have synchronicities to others around them including the art market. I personally believe that the role of the collective is not solely based on networking but the gentle observation which guides the intuitive nature of how they have understood and read artists’ careers in their national state and, later on, their standing in the international artworld.

These collectives include Raqs Media Collective, Camp and the fearless collective (India); MadeIn Company (China); Theertha (Sri Lanka); Rungrupa (Indonesia); Chelpa Ferra (Brazil); Artists Anonymous, Slavs and Tartar (Germany); gelatin (Austria); The Otolith Group, Archive of Modern Conflict, United Visual Artists (UK);

DumbType (Japan); Chto Delat, AES+F (Russia); Dis, K- Hole, Exteriority, Bernadette Corporation, Claire Fontaine, Bruce High Quality Foundation, Etoy Corporation, YAMS, and slightly earlier collectives Goat Island, Ant Farm, guerrilla girls (USA); GCC Gulf Coperation Council (Gulf and beyond) and the Arab Image Foundation (Lebanon).

Often multidisciplinary, they quickly become known for thoughtful, provocative reassessment of the absolute history of authorship that inadvertently questions who presents representation. A large amount of their activities include rewriting from a participative turn that shapes histories rather than history towards an allowance for complexity.

In many cases, artists’ careers do progress in leaps and bounds, whether in terms of sales, media attention, the scale of work or even critical acclaim. All of these do attract the apprehensive eye from other artists, but also from places where the artists’ career is under scrutiny by roving curators. The artists’ remains a subject of research, specifically what and how artists’ work is programmed and placed or of their proximity to specific goals, commercial or other.

An artist who approaches the idea of success as sales of work or even by accumulative adulation can as easily be reined in by ‘circuit breakers’ that maintain the steady course of development. The recent case of performance and visual artist, Terence Koh, whose career was short but meteoric is a key example – from major exhibitions on both sides of the Atlantic, to commercial galleries as well as his involvement with pop celebrities, all of this did not protect his practice.

Surprisingly, Koh is not the first or last to emotionally and physically surrender to the pressures of performing as a lifestyle, many others have to live up to the storyline as institutionalised tags or instant commercial success can become toxic.

A balanced, persistent and measured approach, one you are compelled towards is needed. One wherein many conversations can be had and each conversation does not need be a test but rather a coming together of ideas and experiences. There is no set career path in the arts. It might even be seen by some as incoherent, a process that unfolds on its own timeline, dependent as well as moving at an independent pace that needs maintaining but not necessarily without critically speculating its myths and ones own mythologizing. What better field to test oneself than to curate and work experimentally to make sense of the whole?

In other words, be one of the people who has something—not just aesthetically, art historically, or career-wise—at stake, but one who once in a while tests historical and curatorial contingency.

在很多情況下,主要進行表演行為實踐的藝術家們往往因他們作品中的自傳式敘事而為人所了解。本文以身份問題為主要線索,討論這個問題帶來的結果以及面對的期許,即行為藝術家在更廣大的話語之中經常需要面對的限制性框架、市場行為以及戲劇化評價等;這是如此的一條道路,行為藝術家中的一些人從此開始了某種形式的自我策展實踐,以在藝術世界中展現自身。

藝術世界(artworld)這個詞彙是由俱有影響力卻不再對藝術世界抱有幻想的重要藝術評論阿瑟·丹托 (Arthur Danto)創造出來的。“丹托的定義是這樣的:某物只有在滿足以下條件之後才是藝術作品:(i) 該事物有主題 (ii) 該事物有關於該主題有一定的態度或視角(有一種風格) (iii) 該態度或視角(或稱風格)使用著一種修辭缺失(一般是比喻性的),這缺失通過觀眾的參與填補空缺,(iv) 而這作品以及相關的解讀需求著一種藝術史的語境。”人們關於第四點如何能夠體系化整個定義存在爭議。

在探究這個定義對於作為策展人的藝術家的具體意義時,我們必須詢問一個更加一般性的問題:什麼藝術家被稱作“行為藝術家”,是否就是那些“進行表演行為的藝術家”?

我的論點是,這些藝術家中的許多人以這樣一種顯著的方式被體製化:自傳式附錄對於他們作品的呈現、接受以及歷史化來說,仍然是指向性的。因此,以上的數個條件,包括一個自傳式的解讀均可在藝術家身份認定上使用,尤其是行為藝術家。

“自傳式”標簽最顯著的例子包括充滿激情的德國藝術家約瑟夫·博伊斯(Joseph Beuys)。在1941年,博伊斯誌願參加了德國空軍(Luftwaffe)。同年,他作為一名空軍無線電操作員接受了軍事訓練,後在一次飛機失事事件中存活下來,被墜毀地居民以油脂和毛氈包裹所拯救。這些生活經歷一直出現在他的藝術實踐之中。

他寫道:“然而,在飛機失事後於雪地中發現了我的是他們(當地韃靼人),而德國搜救部隊那時已經放棄我了。在他們發現了我的時候我在昏迷之中,過了整整十二天才於一所德國戰地醫院中蘇醒。所以我所擁有的關於那段時間的回憶穿透了我的意識。我清醒時記得的最後一件事是,現在跳機已經太遲了,降落傘已經不能完全打開了。那一定是墜機幾秒鐘之前發生的念頭。幸運的是,我沒有綁安全帶——我一直不喜歡綁安全帶,更喜歡自由活動……我的朋友綁了安全帶,而他則因為衝擊力被打得粉碎——事後幾乎找不到他的屍首。但我肯定是在飛機墜地之後撞出了擋風玻璃,而這讓我得以活下來,儘管我的頭顱以及下巴受傷了。飛機機尾整個翻起,而我則被埋於雪地之中。這是韃靼人在幾天後發現我的時候我的模樣。我記得有聲音在說:“水(Voda)”,還有毛氈或是帳篷,以及刺鼻的芝士、油脂以及牛奶的味道。他們用油脂包裹我的身體以讓我重新獲得體溫,並用毛氈進行保溫。”

在博伊斯的例子中,他的生平成為了他自我重新解讀的主題並不是一件不合邏輯的事;這段經歷成為了博伊斯藝術家身份的神話般的起源,也為他慣常使用的奇特創作材質——他在許多激烈的公共行為藝術實踐中經常使用毛氈和油脂——提供了解讀的關鍵。

上述的經歷指引博伊斯通過自主再現、知識以及組織的回歸解決了他的心理困境。在這之後,博伊斯建立了德國學生黨(German Student Party),自由國際創造力大學(Free International University for Creativity)以及跨學科研究機構(Interdisciplinary Research)並於1976年參加了德國國會(German Bundestag)競選。在進行先鋒藝術實踐質料以及方法使用的宏觀景觀繪製的時候,自傳式內容以及自我掌控成為了對保守意識形態世界有效對峙的必經之路。

我想要指出,對於進行表演行為藝術實踐或嘗試繼承先鋒藝術創作軌跡的藝術家來說,自傳式存在是刷新民主意識形態的必要策略。

追隨博伊斯腳步的一代藝術家顯著地使用了另一種由藝術家主導的對於存在或在場意識進行的運動。接下來的幾十年內,建立的更多是藝術團體,而不是協會;更多的是群體以及合作運動,而不是國際範圍內關於特定理念形成的聯盟。

在這些團裏,其中一個最重要的是黑山學院(Black Mountain College)。在這裡,各個跨學科的藝術家之間的敘事或因果聯繫為我們提供了一種集體標誌。舞蹈家/編舞家莫思·坎寧安(Merce Cunningham)、編曲家/音樂家約翰·凱奇(John Cage)、藝術家羅伯特·勞申伯格(Robert Rauschenberg)以及巴克明斯特·福樂(Buckminster Fuller)是學院中的佼佼者。凱奇的學生艾倫·開普羅(Allan Kaprow)定義了偶發藝術(happening)並以此開始藝術實踐。壓縮黑山學院的藝術實踐至某個簡單的敘述是不可能的,同樣不可能的是壓縮凱奇或坎寧安的長期、有著重要影響的藝術生涯至一兩句話。他們的作品充滿實驗性,在許多不同的層面上進行創作。黑山學院吸引了一大批日後在美國產生了重要影響的視覺藝術家、作曲家、詩人、設計師,他們的志趣眾多而龐雜,包括“致力於民主管理,並相信藝術對於學習的經驗來說是無比重要的。”

在一個沒有嚴格邏輯確認性或評判標準的藝術世界中,美學問題或市場以及機制問題的解決方案都不是那麼地明晰。

但是,作為一名策展人,在與藝術家們交流的時候,我可以評估他們能夠索取的各種可能性——包括自傳式標簽以及群體建立等的歷史性遺產。藝術家群體建立能夠為贏得公眾以及藝術機構的認可進行有效的準備,並為他們的藝術實踐獲得創作資金以及獲得展覽機會做出鋪墊。藝術史框架以及集體社交行為能夠為理念推廣、明確目標等為了曝光率以及持續性而進行的行為提供便利。

自博伊斯、黑山學院開始,我們逐漸生活工作於物價日益高昂的城市之中,租賃安排逐漸變得不可持續;藝術與奢侈品的共生狀態也扭轉了權威者對於藝術的控制,從而改變了藝術實踐者的狀況。藝術生產者需要與藝術工業競爭,而後者不成比例的力量擾亂了包括信任、善意、慷慨、慈善、資助行為、媒體接觸以及進入私人或國家收藏的機會在內的許多傳統因素。

在許多案例中,畫廊主或他們的助理們介入了許多的關係。正是因為這種破碎的人際關係,藝術理念逐漸被符號的經濟所代替。我們一直在我們的關係之中尋找安全感,儘管越來越明顯的事實是我們為了這個獨特的生活領域建立的模式也已與現實脫節。

從一個策展實踐的角度來說,我希望提出以下幾個讓人興奮的理念展示及於當代環境中運作的模式,這些模式能夠讓藝術家重新以一定的速度進行發展。更重要的是,這些模式能夠為藝術製作者以及活躍於策展實踐之中的人們保留某種獨立性。

我提出以下的這些潮流,以暗示這些脆弱的關係意味著:在進行邊緣藝術實踐——行為藝術、數碼藝術、非物質藝術甚至是作為政治實踐的藝術實踐——的藝術家必須承認在過去二十年內發生的轉變,並必須在自己的工作中加入自我組織這個行為。在很多情況下,他們都遊離於機構策展人以及收藏家的雷達之外。

在兩大重要改變之中,第一個重大改變是藝術家講座以及論文的出現;這是90年代藝術理論與藝術實踐之間出現的倫理邊界的縮影。在這裡,我主要想要關注的是那些自視運作於行為藝術語境內的藝術家。在上世紀70年代、80年代甚至是90年代開始進行行為藝術以及現場藝術的藝術機構並不能如我們意識到的一般關注這種模式。

大量進行寫作的藝術家之中,主要包括:西托·斯特爾(Hito Steyerl)、哈倫·法洛基(Harun Farcoki)、利亞姆·吉利克(Liam Gillick)以及拉比·姆魯埃(Rabih Mroue)——這些藝術家都以一種全球的視野進行寫作,與焦慮文化的現實相吻合,呈現了一種模擬社會意識的告誡式敘事。

一個有關市場以及體系對於展覽策劃給予的支持的因素是,藝術家實踐的崛起往往是與e-flux的郵件訂閱服務密不可分的。E-flux日益龐大的大型數據庫以及激進的、實驗性的理念-這些是e-flux編輯團隊作為全球藝術機構的專業推廣中介的重要行為-已經有效地為大批藝術家提供了一系列的機會和有利環境;e-flux成功地將對於批評人、演講者、表演者以及進行影像創作的藝術家來說重要的數據和潛能聯繫了起來。在最初,e-flux的期刊以及會議會呈現一群相近的藝術家,進而這些藝術家被推廣至各藝術機構由策展人策劃的展覽之中,這些藝術家的作品繼而被相應的收藏所購買,最終為商業藝術市場帶來回報。

這一種基於一群知識份子共同協作完成的當代模式在最初只是由包括賽恩斯博利視覺藝術中心(Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts)以及蓋迪基金會(Getty Foundation)在內的數個機構進行支持,但迅速地,包括frieze雜誌在內的藝術刊物也參與到了這個潮流之中-frieze希望在近年建立一個獨立的藝術教育體系。

在此總結這種協作實踐模式:在市場以及策展活動之內的視角以及藝術服務能夠非常有效地將數據、信息等與正在崛起的相關哲學提供橋梁。在這個意義上,這種模式構造了一種網絡,在這種網絡之中一大批藝術家得以規律性地在世界範圍內的眾多相關美術館以及機構之中進行展覽活動,並在藝術教育機構之中教授策展課程;這種話語框架被認可是與現實相關的,甚至在市場中造成了影響。

第二種有著相對小影響力的平臺更多地與地域話語相聯繫,而不是與政治話語相聯繫,這種模式被稱作是擴展中的敘事。這種模式的內容對虛構的或非虛構的場所做出反映,進行行為式授課、裝置藝術並製作收藏級別出版物,代表者包括Simon Fujiwara以及Slavs & Tartars。

這些藝術家依賴基金會、雙年展、藝博會的委託製作項目,並同時與商業畫廊合作。他們的作品包括物件、影像等,但更重要的是,獨特的創作過程允許他們在不同的層面上進行藝術實踐-自我策展、出版物、物件、影像或紀實錄像等都被當作商業產品被售賣。

在過去,提交研究成果作為藝術實踐的策略一事往往只是與高等教育機構的研究經費相聯繫,因為這行為往往是基於策略重組而做出的不可靠的、迷惑性的平衡;斯拉夫和韃靼(Slavs & Tartars)的地域語言學網狀包裹研究或藤原西蒙(Simon Fujiwara)引人深思的旅程-包括調查考古、旅行、以及性別研究等-則依賴對於特定相關性的發覺;他們的努力贏得了資助者持續的投入,而這繼而為他們帶來了重要的策展獨立性。

對於藝術家創作過程的癡迷以及對於困難計畫的支持對於資助者來說有著非常有趣的角色-資助者因而作為合作製作者對藝術實踐以及計畫作出貢獻;馬休·巴尼(Matthew Barney)的行為作品向宏大的《懸絲(Cremaster Cycles)》系列的轉變就是這種角色的代表性體現,藝術家電影也因此得以成為大型電影作品。《懸絲》系列是作為電影長片由巴尼的紐約畫廊主芭芭拉·格拉德斯通(Barbara Gladstone)製作的,這系列影像作品被視作是藝術家實現策展野心的典範,也被視作是處理一個困難的、工業化了的藝術類型的重要成就。

很快變得明朗的是,作為淩駕於不受限制的集結之上的權威的藝術家往往傾向於使用這種模式。瑞安·特雷卡丁(Ryan Trecartin)為紐約新當代藝術博物館三年展(New Museum Triennale)與他人共同策劃的《包圍觀眾(Surround Audience,2015)》提供了一種裏程碑式的環境安排,這安排“反映了有關多現實的感覺,或,最起碼,回應了這樣的一種想法:數碼科技已經完全把我們體驗世界的方法切割得支離破碎。” 特雷卡丁的作品展於威尼斯雙年展,他也接受了來自德國柏林KunstWerk、倫敦Zabludowicz收藏等機構的委託創作項目。這些成就允許他將自己的群體參與意識置入紐約藝術家群體Dis Collective之中,並共同擔任2016年柏林雙年展的策展人。

最後,我想要指出,藝術家群體在近幾年的活動通過允許藝術家進行自我抉擇,並對固有階級性的“不可見”以及“無力感”宣戰,加強了一種特定的生產方式。

許多藝術家團體成功地進入了策展領域,而他們作為策展人的存在於藝術領域越發重要。他們與身邊的環境進行著相似的選擇-這環境包括藝術市場。我個人相信,團體的角色的重要性不僅僅在於有利於進行社交;藝術家團體是基於他們對於國家內以致於國際層面藝術家生涯的細微解讀而建立的。

這些團體包括:Raqs Media Collective、Campe and the fearless collective(印度);沒頂公司(中國);Theertha(斯裏蘭卡);Rungrupa(印度尼西亞);Chelpa Ferra(巴西);Artists Anonymous、Slavs & Tartar(德國);geletin(奧地利);The Otolith Group、Archive of Modern Conflict、United Visual Artists(英國);

Dumb Type(日本);Chto Delat、AES+F(俄羅斯);Dis、K-Hole、Exteriority、Bernadette Corporation、Clair Fontaine、Bruce High Quality Foundation、Etoy Corporation、YAMS、以及年代更為久遠的Goat Island、Ant Farm、guerrilla girls(美國);GCC Gulf Coperation Council(海灣地區),以及Arab Image Foundation(黎巴嫩)。

這些藝術家往往是跨學科進行實踐的,他們很快因思想性、關於權威絕對歷史的聳動性重新評估而為人所熟知。他們的活動包括大量以“參與轉向”為出發點完成的對歷史的重新書寫。

在很多情況下,藝術家的生涯時而前進,時而停頓-無論是銷售、媒體關注、作品的規模或甚至是批判性評價。所有的這些都吸引著其他藝術家的目光,但同時也要接受策展人的審視。藝術家仍然被視作是許多研究的主體,尤其是他們展出的作品以及這些作品被展出的方式、地點,或是他們與某些特定目標-商業的或是其他類型的目標-的距離等。

嘗試追求商業成功或甚至嘗試通過諂媚式行為的累積獲得成功的藝術家能夠很輕易地被控制著藝術工業發展軌跡的人物收編麾下。在最近,進行行為藝術以及視覺藝術創作的藝術家許漢威(Terence Koh)短暫而耀眼的職業生涯便是一個很好的例子-他在大西洋兩岸都舉辦了重要的美術館展覽,在商業畫廊獲得了成功,與流行明星有著緊密的聯繫,然而這一切都不能為他保全持續的藝術實踐。

讓人驚訝的是,許漢威不是第一個,也肯定不是最後一個因為感情上以及生理上無法承受壓力而放棄了行為藝術的人。許多其他的藝術家也需要承受體制化了的名聲的壓力,而突如其來的商業成功也可以為事業帶來損害。

藝術家需要一個平衡的、持久的、經過規劃的創作方法,藝術家必須督促自己去尋找這樣的一種方法。這種方法帶來許多交流的機會,這些交流不必是對於藝術家自身的測試,而應當是分享眾多理念與經驗的平臺。在藝術領域中,沒有既定的職業規劃。有些人甚至可能會認為這種狀況是非邏輯的。這個過程在自身的生命之中展開,依賴於其他事物,同時也保持著一種獨立的步伐,也需要藝術家批判性地考慮這領域之中的諸多神話,以及自身關於自己所講述的神話。有甚麼比這個領域-在這領域中,人們得以實驗性地進行創作以及策展實踐-更好的理解世界的領域嗎?

換句話說,在這個領域中,你將擁有某些獨特的事物-不僅僅是美學上的事物,可以是藝術史中的知識,或是擁有一個事業-但也將挑戰歷史性的以及策展性的不確定性。

Other Views

“It was commented that artists can do without curators and writers etc, but not vice versa. Of course power structures are problematic but it is ridiculous to even speak of art today without recognising that visibility structures produce the work we examine . Art as we know it is produced by a complex web of actors and the further we go towards recognising and utilising this the better.”—Dr Becky Shaw, artist, research tutor at Sheffield Hallam University.

“以前的觀點是,藝術家沒有策展人和寫手也可以,但反之就不行。權力結構當然是有問題的,但是如果到現在還不能意識到可見性結構確實構建了我們正在討論的作品,甚至是藝術,那才是荒唐的。我們所知道的藝術是一張複雜大網上各個演員各司其職的產品,我們對此認識越深入,利用得越好,對藝術便越好。”--貝奇·肖博士,藝術家,謝菲爾德哈勒姆大學研究生導師。