Interview with Richard Wilson

專訪藝術家理查德·威爾遜

TEXT BY 撰文 x Rajesh Punj 瑞傑希·龐治

TRANSLATED BY 翻譯 x Bowen Li 李博文

IMAGE COURTESY BY 圖片提供 x Richard Wilson 理查德·威爾遜

Artist Richard Wilson RA in front of Slipstream at Heathrow’s new Terminal 2 © LHR Airports Limited. Photographer Anthony Charlton.

Slipstream is one of Richard Wilson’s most innovative projects to date. Originally based on the induced motion of a car rolling over, translated into the aeronautical endeavour of a small propeller plane turning through the air at high altitude; Wilson’s elevated aluminium clad sculpture, twists through the central space of the redesigned new terminal building like an elongated spacecraft settling for earth. And as the motive for our meeting, this titanic sculpture serves to facilitate what is a remarkably candid conversation about his original appetite for the grandiose scale of American sculpture, and of its influence upon his more substantial interventionist works. His indicative need for a ‘wow’ factor when drawing an audience in, and of his wish to redress the notion that his works are in any way acts of ‘vandalism’. Throughout Wilson advocates for more rudimentary principles, referring to ‘honesty’ and ‘integrity’, ideals that he argues are slipping away from a lot of leading artist’s practices now, in favour of more commercial interests. All of which makes Wilson a sculptor in the purist sense.

《尾流(Slipstream)》是英國雕塑家理查德·威爾遜最為大膽的作品。這件巨型雕塑作品模擬了機動車在路面翻滾以及小型螺旋槳飛機在高空航行的動態。像是一架宇宙飛船準備降落地球一般,巨型鋁製雕塑《尾流》扭曲地漂浮於倫敦西斯羅機場新航站樓之中。從這件作品開始,我們與威爾遜討論了他對美國巨型雕塑的偏愛,以及這風格對他充滿介入感的大型雕塑作品的影響;他對公眾積極反饋的需要,以及他對作品的破壞性的辯護。威爾遜在這次談話之中大量提及了如誠實或尊嚴等基本創作原則。對他來說,許多成功的藝術家已經放棄了這些原則,並更多地尋求商業利益。這一切堅持為威爾遜保持了雕塑藝術家身份的純粹性。

————

ART.ZIP: Possibly we should begin by your explaining and exploring the significance of your new work, ‘Slipstream’, and of how important the scale of this work is?

ART.ZIP: 我們或許應當從您的新作品《尾流》開始。請您給我們講一下這件作品的寓意,以及創作規模的意義。

RW: It’s an interesting question relating to scale, because first of all the obvious question people will say is it’s ginormous, why? And you have got to understand I have spent a good part of my professional career as a sculptor; dabbling with architecture, playing with architecture, undoing it, and therefore I’ve had to take on that scale. Therefore if you have an idea about spinning a facade, you don’t do it as a six foot piece. A facade is looking at the extremities and thinking what will the budget allow for? So obviously architecture is a dedicator for scale, and the other thing is the canvas that I was given, which is the empty void of the covered court area. Which is supported in the middle by eleven columns, and in relation to the brief that I was given, was that the sculpture could only be supported off of the columns. So I have only used four of them, and I have probably used just over a third of the supports for the ceiling.

So in that respect it’s not a very big sculpture; but it is big when you see it. And it’s to do with human scale, non-human scale, and architectural scale. So I’ve worked with the scale of the room, and I’ve worked with the scale of the interior of the architecture. It’s not as big as the building; it’s only in one third of the building. You have got the car-park arrivals area from London, and then you have the covered court area, and you have the terminal. So I have got the middle piece; and I’ve taken four of the eleven columns of the middle piece, therefore it’s not a sprawling work that occupies three parts of the architecture, it only occupies one part of it. So in that respect I think it is right for where it is, and the size is right for where it is located.

And in terms of the visual people like to see exciting things, dramatic things, and things that are going to arouse them, and dazzle them in some way, and startle their imaginations, and I think I work on that level. It’s a little rude in the sculpture world, but I use it, and I suppose I use it because I am working a lot of the time in an environment where my audience isn’t well versed in an art grammar. Here we are at an airport where 20 million people a year come through this terminal, then they are not all going be au fait with the visual arts; they (the audience), have not had the training I have had, so I have to use something that gets that wow factor going.

RW: 創作規模是一個有趣的問題,因為這個作品對所有人來說都是巨大的。為甚麼?你要明白,我一直是這樣工作的:進入建築領域、使用建築元素、解構建築,因此自然地,創作規模是一個很重要的考慮因素。所以,如果你想要扭轉一個建築的立面,一個六英尺大小的作品並不足夠。任何一個西式建築立面都與極限有關,當然也與預算有關。所以理所應當地,建築總與“規模”息息相關,而我能夠使用的創作空間就是候機樓巨大的中庭。中庭里有十一根承重柱,我的作品只使用了其中的四根,只佔用了三分之一的天幕支撐。

所以,在這個意義上來說,這件作品並不是一個無比巨大的雕塑;但親身體驗這個雕塑時你還是會感覺到它的龐大。這與人體大小、非人體尺度以及建築規模有關。創作的規模根據空間的尺度以及建築內部大小進行調整,我只使用了整體建築的三分之一左右,而不是整個建築的全部空間。整體建築包括停車場、中庭以及候機樓。我只使用了整體建築的第二部份,借用了四根立柱,所以這不是一個盤踞著整個巨大建築的雕塑作品。我想,在這個意義上,這個雕塑適合這個空間,大小合宜。

視覺上,人們喜歡令人興奮的、戲劇性的、聳動性的、能夠讓人暈眩、激發人想像力的東西,我覺得我在基於這樣的標準進行創作。對於雕塑界來說,這樣的創作可能有些粗魯,但是我必須這樣做,因為我經常要在一個非專業藝術語境中進行創作。這个候機樓每年接納超過兩千萬來自世界各地的旅客,我們不能指望每一個旅客都熟悉當代視覺藝術。他們沒有接受過我曾接受過的訓練,而我要為了讓他們興奮而創作。

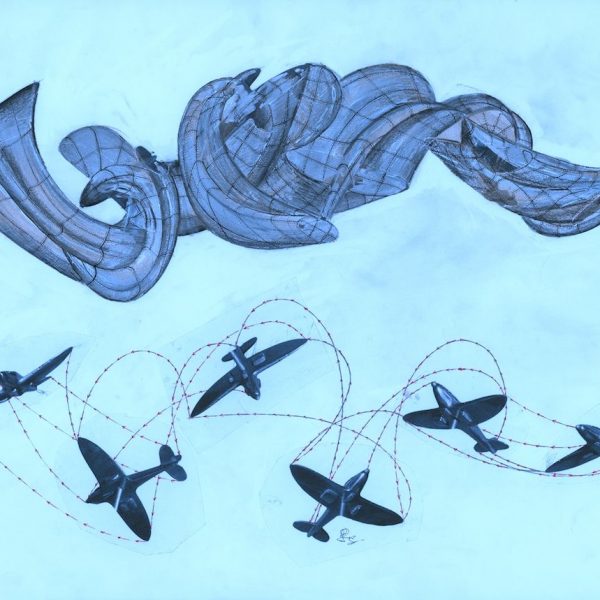

- Artist’s sketch of Slipstream © Richard Wilson RA

- Slipstream by Richard Wilson at Heathrow’s Terminal 2 | The Queen’s Terminal. Photograher David Levene. © LHR Airports Limited

- Slipstream by Richard Wilson at Heathrow’s Terminal 2 | The Queen’s Terminal. Photograher David Levene. © LHR Airports Limited

ART.ZIP: You appear to consider the external factors of a work, (the volume of space you begin with, and your wish for the work not to overwhelm that setting in any way), as much as the work itself; am I correct in thinking that?

ART.ZIP: 對你來說,創作外部因素--包括空間的大小,以及創作規模的合宜性等等--似乎與作品本身同樣重要。我這樣說對嗎?

RW: I think that’s true, and I think that one learns to be very sensitive, and that comes through various reasons. And it is something I have had to really think about, and work with over the years, because I spoke about the idea that you can make constructions and build, which is what this is. Or as a lot of my work in the pass has done, which is to unravel and undo, and look inside of architecture. When you do that, you tend you get critics talking about the artist as being a vandal, that I am attacking architecture, and disagreeing with the architect; and it’s not that at all. Because they are sensitively choreographed pieces; so when you do turn the facade of a building, or plant a sculpture in the floor of a gallery, or take a window and bring it into the space to adjust the architecture, it’s all incredibly thought out and sensitively worked. I wouldn’t say hundreds, but there are lots and lots of drawings, sketches and models made, to get it to sit properly and right in the space. It’s not an attack, it’s not an act of vandalism. I’m not the mad axe man coming in to attack architecture, as has been written about me. So I have had to think about it.

RW:的確是這樣的。出於很多原因,一個藝術家要學會變得敏感。這是我要經常考慮以及面對的事情,因為在某些情況下你可以提出一個計劃並開始建造,一切非常順利。有時候,就像我過去常做的那樣,你想要消解、鬆弛並探究一個建築的內部。評論家們經常把這種作品視作是一種蓄意毀壞,把我視作是攻擊建築的人,對建築師的創造有異議的人。但事實完全不是這樣的。我過往的創作全部都經歷過仔細的架構和縝密的考慮。所以,無論是扭轉一個大樓的立面,還是在畫廊的地面上立起一個雕塑,或是在一個建築中放置一個窗戶以改變這個建築空間,這些都是經過深思熟慮的、都是細緻地構架出來的。每一件作品在實現之前都需要大量的繪圖、草稿、模型,以達到理想的結果。這些作品不是對建築的攻擊,我也不是在蓄意毀壞某幢建築。我不是人們口中的那個拿著斧子攻擊建築的瘋子。所以我需要考慮這些事情。

- Turning the Place Over, European Capital of Culture Project, Liverpool © Tony Wilson / Courtesy of Richard Wilson RA

- A Slice Of Reality, Greenwich Peninsula, London, 2000 © Richard Wilson RA

ART.ZIP: That comes across as a strange accusation, for someone so deliberate in everything that they do. Are you?

ART.ZIP: 對於如此謹慎的人有這樣的一個指控實在有點不能理解。

RW: I can understand it, because what it is, is that often people don’t know the hidden agenda, and I am referring again to these pieces I have just mentioned, (Over Easy 1998, The Arc, Stockton-Upon-Tees; Turning the Place Over 2008, Liverpool; Water Table 1994, Matt’s Gallery, London), when you know you have been given permission to undo a window, and you have a very good understanding of how that window operates, as in She Came in through the Bathroom Window 1989; I could just unbolt it, bring it back in, and put it back up afterwards. I knew with Turning the Place Over 2008, I could do a pastry cut in the building, mount that onto a spindle and spin it, because the building was going to be pulled down afterwards; so those were the hidden agendas, given that information. The same with the Serpentine Gallery, Jamming Gears exhibition, in 1996; they, (the gallery), were going to excavate their basement out. And they had been given lottery money to put an education room down there. Therefore I could dig the floor, because when I’d gone it was all coming up anyway. So there was an understanding that I would use the parameters of what was allowed and doable; and in that respect I probably challenge the architecture in that way. Where as in the museum environment, it is one where the architecture is sacrosanct, you can’t put a nail in the wall, you can’t undo that floorboard; you know it is difficult enough taking a light bulb out, there are so many health and safety restrictions. So I research all of those things, and just basically determine what the available parameters are, and then work out what I can do within the parameters as I understand them. It is not vandalism, it’s not that I go in and don’t ask, or seek permission, and just assume I can do these things.

RW:我能理解這些指控,因為人們通常不清楚藝術創作的背景。我在討論的還是那一系列作品(Over Easy 1998, The Arc, Stockton-Upon-Tees; Turning the Place Over 2008, Liverpool; Water Table 1994, Matt’s Gallery, London):舉例來說,在《她從浴室窗子爬進來(She Came in through the Bathroom Window, 1989)》之中,我清楚那個特定窗戶的功能,也已經獲得許可,所以我能夠把窗戶卸下來,放入室內空間的中心,再放回原位。在創作《翻轉空間(Turning the Place Over, 2008)》的時候,我可以切開一個大樓立面的一部分、為這一部份安上軸、任意旋轉這一切面,因為這整幢大樓在此後將被拆除。這些細節是我藝術創作的背景。1996年在倫敦蛇形畫廊(Serpentine Gallery)完成的《卡住的齒輪(Jamming Gears)》也是這樣。那時,畫廊已決定要挖空他們的地下室。他們獲得了英國國家樂透的資助,將在地下一層建立一個藝術教育廳。我之所以可以挖空畫廊的地板進行創作,因為這地板無論如何是要被拆掉的。所以我一直都是在與空間達成共識之後,在可行的範圍內進行創作的,在這個意義上,我可能在某程度上挑戰了一些建築空間。在一個美術館環境中,建築的地位是至高無上的,你甚至不能在牆上釘釘子,更不要提掀起地板了。光是取出一個燈泡就要經歷許多安全保障手續,已經是非常困難的事情了。所以在創作的時候我對所有這些情況進行研究,努力了解一系列的限制性因素,最終在這些限制之內進行創作。我的創作不是蓄意毀壞,我並沒有走入一個空間,甚麼也不問,不尋求許可,就假設我可以進行那些創作的。

————

ART.ZIP: How integral is drawing when planning a work?

ART.ZIP: 在計畫進行當中,繪圖是其中一個重要組成部份嗎?

RW: Drawings are vital for me, because number one I am working with teams, and I have got to be able to express my idea sensibly, and in a coherent way, so that there is no misunderstanding. Sometimes I am invited to make drawings and models to assist in the securing of funding, so you would be asked to make a maquette in order to convince someone who is not that well versed in the art grammar, that they can say oh I get it, I like it, let’s put money forward into that, so it will be a local authority perhaps.

So these things are done to the best of my ability, in order to convey the best possible way the concept as it is at that moment in time. The other thing the drawings are done for is, in the same way people go to the gym to work-out, I use drawing as a mental limbering up. I have got to get very familiar with my work, because once I am familiar with it, it is handed over. Made in Hull, (referring to the slipstream sculpture), and assembled here. It’s not done in the studio where you get time to look and duel upon it and change things, you have got to get it right, like the architect’s got to get it right. And you can’t be seen to be wasting money; you can’t say actually I don’t like the middle, can we get rid of that and do it again, because you look unprofessional, and you are throwing money away at that point.

RW:對我來說繪畫非常重要。因為,第一,我與一整個團隊一起工作,我需要清晰流暢地表達我自己,不能帶來任何誤解。有時候,為了獲得資金支持,我需要提供繪畫以及模型。所以我需要搭建一個小型模型來說服不熟悉藝術語言的人--比如某地政府部門--讓他們理解、欣賞,並願意出資實現某個作品。

我總是儘我所能完成這些事情,以最好的方式傳達某個概念。另一方面,就像人們會去健身房鍛鍊一樣,我把繪畫視作一種精神鍛鍊。我必須非常熟悉每一次創作,因為我不能完全掌控整個創作過程。舉例來說,《尾流》是在英格蘭東北部城市霍爾(Hull)製作,在倫敦完成組裝的。因為這不是在工作室裡完成的,所以我沒有時間仔細打量它或做甚麼改動,我需要一蹴而就,就像一個建築師一樣。我也不能浪費錢;我不能說這樣的話:“我其實並不喜歡中間這一部分,把這一部份扔了重做。”,那樣就太不專業了,錢也打了水漂。

ART.ZIP: There must be a point with certain projects then when you are having to be much less attached to a work, as with Slipstream. Where you are less able to come back to something, and have the opportunity to amend it whilst it is under construction. How do you operate under those circumstances?

ART.ZIP: 的確,在實施計劃的過程中,總有你不能親身監督的時候。在那些時候你不能回頭考慮各種細節,在製作過程中你也沒有改變作品的機會。你是怎麼處理這些情況的?

RW: With Slipstream, and any of the other major works where the sculpture is rooted in a building outside a big gallery idea, it requires of me to work like an architect; that is you work, and work, and work on the idea, to get it fine-tuned to what you consider is correct, and then you hand it over to the engineers, and onto the manufacturers; and at that point you don’t lose control on it, but you obviously can’t chop and change it after that. And when a project like this takes three years, you most intensive period is probably the first six months, at the very beginning. After that you are following it, signing bits off, saying I don’t like the way those bits work, or can we just clean that there, or I don’t like that bit there, but essentially you can’t challenge your own aesthetic. You can’t say I don’t like the way I have made that work, can I get rid of all of that.

RW:在創作《尾流》或其他於非畫廊空間完成的大型作品的時候,我需要像一名建築師一般工作。我不斷地修改我的理念,進行細微的調整,直到我覺得一切沒問題了,我再把計劃交給工程師們,然後再轉交給製造方。到了這個時候,我也並沒有完全失去對作品的控制,但是在這之後我就不能做甚麼大改動了。如《尾流》這樣的大型項目一般需要三年的時間,而對藝術家來說,最緊張的時間應當是最初的六個月。此後,藝術家則要跟進和監督計劃的執行,確保計劃的順利進行,給出意見,但總的來說,你不能挑戰自己的創作美學。你不能說:“我不喜歡我自己之前做的,能不能把這些都扔了。”

- Slipstream by Richard Wilson at Heathrow’s Terminal 2 | The Queen’s Terminal. Photograher David Levene. © LHR Airports Limited

- Slipstream by Richard Wilson at Heathrow’s Terminal 2 | The Queen’s Terminal. Photograher David Levene. © LHR Airports Limited

- Artist’s sketch of Slipstream © Richard Wilson RA

ART.ZIP: There is something almost contradictory about your lexicon for public sculpture; when you talk of inevitable ‘compromises’, and of your wish for ‘being sympathetic’ to a space; in relation to the artist as ‘actionist’. Are the two mutually exclusive?

ART.ZIP: 在討論公共雕塑的時候,你使用了一系列相互矛盾的辭彙。你提到了不可避免的“妥協”;你希望作為一個“行動主義”藝術家去“感受”一個空間。

RW: It comes with age, you start to realise that sometimes you can be a bit belligerent, and you think the idea is right; and you have tried and tested it on your models and drawings, and then someone will come along and say it can’t be that high, it’s got to drop down a bit so you can see the exist sign, and you drop it, and you think actually I am glad that surfaced because it could have been a bold, brisk attempt at saying, here I am, flying up and away, when in fact there is a subtly aswell, when you reduce and do those things. Sometimes fortuitously it’s a blessing in disguise, and you rarely say I am glad that went that way, because I had got it wrong; you keep quiet about it, and you pretend it was always intended. But obviously artists have to work in that way all the time. I think everyone has to give and take in that situation. The building has to give a bit, but the sculpture has to give a bit back aswell.

RW:這與年紀的增長有關。有時候你可以很強勢,在進行過各種測試後,你相信自己的想法是對的。然而有人走來對你說某個結構不能那麼高,一定要低一點,否則人們將無法看見安全出口標誌,在接納了他的意見之後,你會感到慶幸,因為這作品不僅與藝術表達的自由性有關,在你對其進行改動的時候也需要進行某種細緻的考慮。有時候這讓人感到幸運,但你不會說“我很高興我進行了這樣的改動,因為我在一開始的時候弄錯了”;你不會去討論這件事,而會假裝你本來就是這樣考慮的。當然,藝術家經常要以這樣的方式去工作。我想,在那樣的狀況下,每個人都需要做出妥協,建築需要做出妥協,雕塑也同樣需要做出妥協。

————

ART.ZIP: You have referred to the significance of scale in your work; how important was American sculpture to you, as an influence?

ART.ZIP: 回到關於作品規模的問題:美國雕塑對你有著重要的影響嗎?

RW: I really used the library, and I became very involved in the American artists at art college. Very involved in Land Art, and I become very involved with scale. (Richard) Serra, Mark di Suvero, and some of the other big land artists, Walter de Maria, Michael Heizer among them. And I came to Gordon Matta Clark very late, after college. But that kind of bravado, the idea that scale and the very American idea that rather than use the path you know, get off the path and make your own trail. That idea that you have something to say, say it; and don’t follow the conservative trend, break away and be your own person; be your own ideas. And I always thought there was something wrong, that if anyone was making work like you that that was wrong; and for me it was about being unique.

RW:我對美國雕塑流派進行過大量的研究,在求學時期我也經常與許多美國藝術家交流。我與大地藝術運動的關係非常緊密,也自然地經常考慮藝術創作規模的問題。我接觸到了包括瓦爾特·德·瑪麗亞(Walter de Maria)、邁克爾·海澤(Michael Heizer)、理查德·塞拉(Richard Serra)以及馬克·迪·蘇維洛(Mark di Suvero)等重要的大地藝術雕塑家。在藝術學院畢業之後我才遇到戈登·馬塔·克拉克(Gordon Matta Clark)。他們的勇氣、氣魄、不走尋常路的美國精神、直接了當的自我表達、不守舊而強調突破的原則…我那時總覺得如果有甚麼人像你一樣創作的話,那一定是有甚麼地方不對勁。對我來說,藝術讓我成為一個獨特的人。

- Slipstream by Richard Wilson at Heathrow’s Terminal 2 | The Queen’s Terminal. Photograher David Levene. © LHR Airports Limited

- Slipstream by Richard Wilson at Heathrow’s Terminal 2 | The Queen’s Terminal. Photograher David Levene. © LHR Airports Limited

- Artist’s sketch of Slipstream © Richard Wilson RA

- Turning the Place Over, European Capital of Culture Project, Liverpool © Tony Wilson / Courtesy of Richard Wilson RA

- A Slice Of Reality, Greenwich Peninsula, London, 2000 © Richard Wilson RA