TEXT BY 撰文 x Peng Zuqiang 彭祖強

It’s interesting to think about how the subject of ‘studio’ has been addressed in contemporary art practices. Studio as a place of making art work, is therefore also the very subject of an artwork. However, presenting Self-reflexivity through a representation of the studio is frequent, without offering a mundane rendition of it can still be a challenging job, this article takes a look at some contemporary art works that go beyond painterly or photographic portraits of the artist’s space.

“工作室”是如何成為一個題材,在當代藝術中被不同藝術家運用的?工作室本身作為一個藝術創作的場所,同時又成為了藝術作品所指向的題材。在不少作品中,都出現了藝術家的自我分析性,但如何不落俗套,不停留在重現工作室內部原樣,卻也是一番挑戰。本文探索當代藝術作品中,那些不僅僅用攝影和繪畫方式來描繪工作室的作品。

Art studio is essentially a space for making works, and Canadian artist Ian Wallace, the father of the Vancouver School which forms a important chapter on the conceptual art and photography, presented the studio as it is – a place to work. In his 1983 performance At Work, the artist is seen sitting in the front display room of a gallery, reading and pondering in front of a long table. This seems to be a footnote of his conceptual art practice, as Wallace came from an art history back ground, this work is self ironically addressing the stereotype of ‘writer-turn-artist’. During the duration of his performance, the exhibition space is transformed into a studio, the exhibition space also potentially becomes the actual studio space where the artist can research and make work. The start and end point of an artwork becomes one. It also evokes the question, what is the studio space for performance artist. When the medium is the artist’s own body, does it mean the artist body is also the studio as well?

藝術家工作室說到底就是一個藝術家工作的地方,而就這直截了當的表現在了加拿大藝術家伊恩·華萊士(Ian Wallace)的作品 《在工作(At Work)》之中。華萊士是溫哥華攝影觀念主義學派的的重要代表人物,在他的行為藝術作品《在工作》中,藝術家本人端坐在一張書桌前,一只手撐著下巴,若有所思,而桌子則是置於畫廊面朝馬路的展示空間。作品本身似乎是藝術家對自身觀念藝術創作的最佳註腳,華萊士本人是學藝術史出身,而這件作品似乎是把自己這種‘藝評人變藝術家’的身份幽了一默。在表演的過程中,畫廊的展覽空間也變成了一個工作室,一個藝術家可以真正工作和研究的空間。於是一件作品的誕生和展出地在此形成了統一。但這個作品也同樣提出一個問題,如何定義行為藝術家的工作室,當藝術創作的媒介是身體本身,藝術家的身體也可以被看作是工作室嗎?

Nonetheless, the studio space is just as any other domestic spaces, where small incidences happen, such as mice problems, recorded in Bruce Nauman’s video installation Mapping the Studio. In the installation environment, there are seven projections on different walls, the artist used cheap video camera to record his own studio space for the duration of a whole night. He later repeats this action over a three month period. The footages reveal the other side of the studio when the artist is not present. And as the visitors are invited to sit on the rolling office chair in the centre of the space, almost acting as a security guard looking at the CCTV footage of his studio space, while we are expecting something to happen, most of the time it disappoints us with little actions. However, the minimum action does not mean there is nothing going on. The soundtrack of the ambience reminds us that a studio space is never empty, there is wind, mice, and many other sounds. The work reminds us the durational shots of many contemporary cinematic masters. It also requires patient and time. It fulfils the desire of voyeuristic curiosity of the viewer who want to look behind the scene, but the space under surveillance is actually a completely safe and secure domestic environment.

無論如何,工作室空間其實也跟其他的室內空間一樣,充滿意外和驚喜,例如那些四處逃竄的老鼠。這個例子就被記錄在了布魯斯·勞曼(Bruce Nauman)的影像裝置《工作室測繪(Mapping the Studio)》之中。在這個裝置環境中,七個投影分別投射在四方的空間中。藝術家用簡陋的攝像機,整夜拍攝自己工作室中的數個角落。這樣的記錄持續了三個月,而所集成的影像則給觀眾呈現了當藝術家不在場時,藝術工作室的另一番景象。觀者們被邀請坐在空間中心放置的旋轉辦公椅上,扮演著類似監控室保安的角色。而當觀眾期待影像中能發生些什麽時,這些記錄卻在一次次讓我們失望。這並不代表空間中沒有事情發生,伴隨的背景聲音:風聲,噪聲,老鼠聲提醒著觀眾,工作室空間從來都不是空的。影像的風格令人聯想到當代影壇諸多大師的固定長鏡頭,它考驗著觀眾的耐心,並提供一種對於時間的新體驗。作品一方面或許滿足了觀眾對藝術家私人空間的好奇心,然而荒繆的是,這樣一個閉路鏡頭下的空間只不過是一個安全而平凡的室內空間而已。

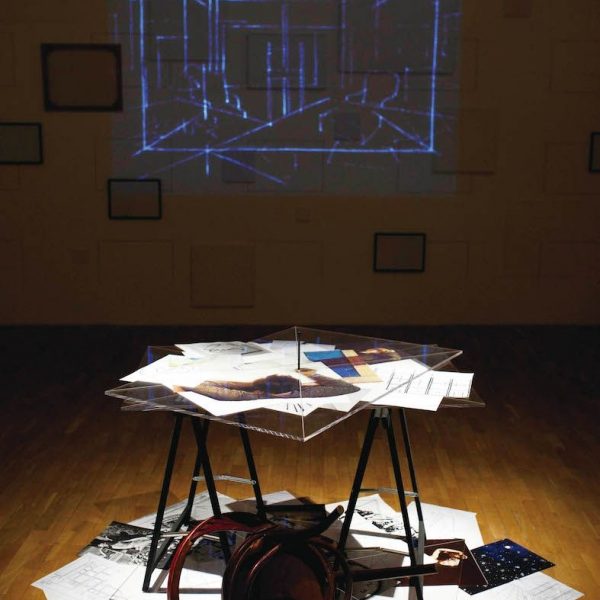

The environment of the studio certainly reflects the style and work of an artist. And many artists has thus used studio as a medium to tell different stories. In the current exhibition of Giulio Paolini’s at the Whitechapel gallery, several conceptual works in the exhibition presented different personality of an artist… The installation titled Big Bang is a sculptural rendition of a corner of the artist’s studio itself. In the installation, we see a chair, surrounded by paper balls of possibly discarded sketching of his works. In front of chair erects a plexiglass box which contains a miniature of the artist’s studio – again an empty chair with an empty easel. What we are seeing here is an artist frustrated with ideas. Another work in the same exhibition, (The Author Who Thought He Existed (Curtain: Darkness Falls Over the Auditorium) is a room scale environment which consists of a knock-over chair, a table on top of which sketching, photos and images are pinned together through a pencil. On the opposite wall space, a projection of his drawing works are projected onto some empty canvas and frames. In this case, the absent artist is portrayed as someone who can’t seem to continue working and thus abandoned the studio space. The studio here is almost similar to a theatre set, the audience is supposed to imagine what happened in the studio and also what happened to the artist. It is self-reflexive with a humorous twist.

工作室的環境或許是對藝術家風格的最佳反應。很多藝術家也將工作室當作一個題材來進行敘事。在倫敦白教堂畫廊正在展出的吉里歐·帕奧里尼(Giulio Paolini)個展中,藝術家的幾件觀念藝術作品便試圖講述藝術家的不同形象。名為《大爆炸(Big Bang)》的作品,是藝術家工作室一角的雕塑化呈現,在作品中,我們看到一個藝術家的座椅被周圍不少廢棄紙團所包圍,這些紙團或許就是被藝術家所放棄的草稿。椅子前擺著一個透明的塑膠玻璃箱子,裡面像是一個藝術家工作室的另一個角落:一個空椅子面對著一個空畫架。我們看到的或許是一個筋疲力盡,費盡心思的藝術家形象。展覽中的另一件作品《覺得自己是存在著的作者The Author Who Thought He Existed (Curtain: Darkness Falls Over the Auditorium)》是一個空間裝置,展區中放著一張被推翻的椅子,桌上堆積著許多草稿和習作,都被一支鉛筆定在了桌面上。對面的墻上掛滿了大小不一的空畫布和畫框,而藝術家的鉛筆畫則被投影於其上。在這個裝置中,我們看到的或許是一個已經無法工作,一氣之下推翻椅子,離開工作室的藝術家。在帕奧里尼的作品中,工作室就像一個話劇舞臺,裝置的布置讓觀者自己聯想藝術家的身份,猜測藝術家之前的行為。幽默之余,卻也充滿了自我反思性。

In Paul McCarthy’s film Painter, studio is used as a space of critique. In the film, the artist was dressed as someone between a clown and a painter, or both. Exaggerating all possible clichés of the ‘male genius painter’ through his performance, as he uses his huge paint bushes to surface the walls and canvas in his studio. McCarthy here is mocking the late career of abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning, who was said to be a selling out during his last years. When the artist in the film started to shout at his curator, who has a similar clown face: ‘You haven’t been to my studio for almost a year… you owe me a lot of money.” He also reminds us the studio is also a contact zone, between the artists and those who see the works before they are shown to the public.

在保羅·麥卡特尼(Paul McCarthy)的影像作品 《畫家(Painter)》中,工作室成為了一個用以批判的工具。在短片中,藝術家裝扮成近似一幅小醜的模樣,大肆用力地演出“男性畫家”們可能有的各種“典型形象”。麥卡特尼舉著一個大得離譜的筆刷在墻和畫布上肆意舞弄,藝術家在這裡正是在嘲諷抽象繪畫大師威廉·德·庫寧(Willem de Kooning)在藝術生涯晚年近似流水線生產效率的藝術創作。當影片中的藝術家對著他同樣穿著小醜裝扮的策展人咆哮道“你有一年沒來我的工作室了…你欠了我不少錢!”的時候,在滑稽之余,麥卡特尼的短片也提醒著觀眾,藝術工作室也是一個充滿互動的空間,藝術家和一些最先看到未完成作品的來訪者在此交流。

Liam Gillick’s Everything Good Goes, is a 15 minutes long video, depicting an artist, listening to a lecture performance while constructing a 3D factory plan on his computer. The video was shot in a studio space, as the camera patiently surveys the studio space from the key board to the computer screen, from the hand of the mouse to the computer table that holds everything together. At the same time, the lecture recorded in a telephone voicemail directs both the cameraman and the viewers in terms of how the model-building process should be created. In this rather contained space, everything looks grey and sharp. This work is not only a tribute to Godard, but also a faithful reflection of the artist practice, as someone who works closely with architecture and design, as well as theory. We can’t see the artist, but we are seeing, listening and thinking with the artist, constructing another space in his studio.

利亞姆·吉利克(Liam Gillick)的《一切好的東西都要消失(Everything Good Goes)》是一個15分鐘長的視頻短片。片中的藝術家正在通過電腦制作一個工廠的三維模型,同時,他也在聽電話中播放的一段講座錄音。視頻拍攝於一個工作室環境,鏡頭具有耐心地慢慢掃過整個工作室空間,從鍵盤到電腦屏幕,從握著鼠標的手,到整個電腦桌。與此同時,耳邊的那段電話錄音,正指導著攝像師和觀者,如何記錄和觀察整個模型制作的過程。在影像中這個狹窄而有限制的空間內,工作室中所有的事物都帶著一種冷靜和敏銳的質感。這件作品不僅僅是對戈達爾(Jean-Luc Godard)的致敬,同時也反映了吉利克的混合藝術、設計和理論的創作模式。我們看不到藝術家本人,卻在跟著藝術家一同觀察、傾聽和思考,共同在工作室中創造另一個空間。

Tips:

Giulio Paolini: To Be or Not to Be

Whitechapel Gallery 9 July – 14 September 2014

![1. WG. Installation view. Giulio Paolini. Essere o non essere [To Be or Not to Be], 1994-95](https://www.artzip.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/1.-WG.-Installation-view.-Giulio-Paolini.-Essere-o-non-essere-To-Be-or-Not-to-Be-1994-95.jpg)