Text by: Struan Robison / 撰文:Struan Robinson

Translated by: Harry Liu / 翻譯:劉競晨

Noah Cowan, previously co-director of the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) put together the selection of films to be included in the program to reflect this. He writes: “We have aimed to achieve a balance between the canonical and the unjustly neglected, the historically vital and the thematically intriguing, and we have tried to cover as wide a spectrum of the key genres as possible”.

The selection spans the classic 1920’s martial-arts films (wuxia pian, or ‘chivalrous combat films’) to the 1980’s Hong Kong New Wave movement which reinvented them; the Golden Age of Shanghai Cinema to the post war films of the mid century; from household names of the Pre-Cultural Revolution to the Mainland cinema of the Sixth Generation. The centenary travels the breadth of China’s cinematic history and is planned to generate discussion just as much as it is to look back and remember, as Cowan outlines: “Just as we seek to trace a dialogue between cinema traditions, our series is designed to encourage discussion, not close it down”.

2014年6月到10月,英國電影協會BFI( British Film Institute)舉辦了以中國百年電影發展為主題的放映季,整個活動期間包括了各種論壇、講座以及電影放映活動,來回顧和探討這一百年間中國電影的發展歷程。 對於西方觀眾來說,中國這一百年間的電影發展是在國際電影藝術發展史上失落的一環,由於這一百年間戰爭和不停息的社會變革,中國電影的聲音被淹沒在政治的喧囂與社會的動盪不安之中,是次英國電影協會也正是希望借此次《中國百年電影》放映季來為西方觀眾梳理和展示中國與衆不同的電影發展歷程。

因為在這一百年間,中國的社會經歷了翻天覆地的變革,很多電影遺失了,也有很多被禁,而正是在這樣艱苦卓絕的環境中,中國電影產業仍然堅強地生存并不斷發展,也正因為如此,關注和梳理中國的電影發展更顯得尤為重要。前多倫多國際電影節聯合總監諾亞·考恩也是基於這樣的初衷精選了此次參演的電影,他表示:“我們希望這次的演出季能夠在複雜的情況中尋求一個平衡,既能展現不同類別的電影形式,又能兼顧到不偏頗的有所選擇;既能夠從歷史宏觀上把握關鍵的作品,又要讓整個活動的主題生動有趣,我們希望能夠盡力將儘可能多的重要電影作品展示給大家。”

The first Chinese film was a recording of the Peking opera, The Battle of Dingjunshan, in November 1905, Beijing. One fresh new art form (film) recording another’s existence (opera). China’s cinematic beginnings are in the merging of a relatively recent medium with one already long established. So, perhaps it’s apt, therefore, that one of the most critically-acclaimed Chinese motion pictures to find popularity in the West is Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine (1993) – a film which intersperses the telling of Peking opera with the rest of the film’s narrative. When ART.ZIP interviewed Noah Cowan, ahead of the launch of the BFI’s season, he spoke of how this merging of art forms is what separates Chinese cinema from its Western counterparts, explaining: “one of the reasons Chinese cinema is so exciting is that there’s porousness between media and art forms that becomes much fussier when you’re dealing with European cinema”.

The program looks at the period of Shanghai’s golden age of Cinema, one where this new exciting art form knew no bounds, and could present a glittering idealistic vision of what life ought to be like for China’s people. Shanghai presented an anything goes attitude and was “able to shatter age-old taboos and champion utopian ideals”. The early masterpieces The Highway (1934) and Street Angel (1937) were able to “question how the art of cinema itself might be reconceived along progressive lines by experimenting with innovative visual techniques and unusual narrative structures”.

這次演出季播出的作品囊括了從上個世紀20年代經典武俠電影到80年代徹底改變了香港電影的“新浪潮”運動;從上海電影的黃金年代到20世紀中葉的戰後電影;從文革前那些家喻戶曉的名字到今天的第六代電影人。當我們回顧這一百年中國電影發展的歷程,那些過往的片段和逝去的記憶正如預想當中那樣引發了關於中國、關於電影的各種各樣的探討,正如考恩所說“我們希望追尋電影發展中的軌跡,希望通過我們的活動來激發和鼓勵對電影的討論”。

1905年,中國誕生了第一部電影作品《定軍山》,雖然它其實就是翻拍了同名的一部京劇的演出,但這是第一次運用了新的“膠片”形式紀錄了傳統京劇的表演。中國電影的發端就是建立在新藝術媒介與一個已經擁有悠久歷史的藝術形式相結合基礎之上的,這種結合某種意義上來說是非常有效的,這也是為什麼陳凱歌的《霸王別姬(1993)》受到了很多西方觀眾的喜愛──用電影的形式講述了一個圍繞京劇展開的故事。在此次英國電影協會中國百年電影展播季之前,在與考恩先生的採訪中,他也談到不同藝術形式之間的融合方式也是東西方電影發展的一個很顯著的差異,他說:“中國的電影產業令人興奮的一個原因就是在藝術表達的媒介和藝術形式還都並不完善,具有大量的探索空間和可能性,但同比歐洲來說,在完善的體系之下就很難進行大量的有突破的嘗試了。”

As art imitates life, it is no surprise that given the onset of the 1937 Sino-Japanese and the Second World War, several key films of this period should take the war as their subject, most notably among them, Fei Mu’s 1948 masterpiece Spring in a Small Town. A film which would break away from its predecessors’ appeasement of the Communist Party’s demand for the inclusion of leftist subject matter and instead focus more on the inter-personal conflicts of its narrative’s characters. A new print made by the China Film Archive in the 1980’s, would see resurgence in its popularity and lead to it being named as the greatest Chinese film ever made by the Hong Kong Film Awards.

When marking China’s cinematic centenary, the absence of film is just as significant as its presence. Cowan talks of how the Cultural Revolution launched in 1966 “paralysed cultural and intellectual life” in China and would lead to a multitude of films that could never and would never be made. Film and its content became censored with motion pictures such as Breaking with Old Ideas (1975) requiring storyline approval from government officials and characters being rewritten if thought inappropriate. The idea of film as entertainment was superseded by the idea of film as a vehicle for propaganda. Feature film production ground to a halt with virtually no films made between 1967 – 1972, that was until “the mainland emerged from the shadow of this cataclysmic event” with so called ‘scar films’ of the pre-Cultural generation film makers: the Fourth Generation.

Under the title ‘New Waves’, the BFI looked at the Fourth Generation’s attempts to make sense of the ordeal their country had faced in the preceding years. The ‘scar films’ (simple, affecting dramas which focus on individual tragedies) were analysed alongside a Q+A by one of their most well recognized pioneers Xie Fei. Screenings of his films accompanied the discussion such as Black Snow (1990), the story of a petty criminal (Jiang Wen) who returns to Beijing at the onset of the Mainland’s entry into the global capitalist market and falls for a cabaret singer. It paved the way for Sixth Generation luminaries Lou Ye and Jia Zhangke in its portrayal of new China at its most contradictory. There were screenings of one of Wu Tianming’s most well regarded films, The Old Well (China, 1986), a piece of work that would help reshape Chinese cinema.

此次選取的作品中的一部份着眼於中國上海電影的黃金年代,那時候電影這種藝術形式是全新的、天馬行空的,通過當時的電影作品為中國人呈現了和描繪了熠熠生輝的、充滿理想的、美好的生活願景。當時的上海是一片充滿朝氣的土地,在這裡“一切皆有可能”,用考恩的話來說就是“要打破陳規舊俗,要實現烏托邦的理想。”1937年的經典電影作品《馬路天使》就是一個例子,這部早期的電影作品就提出了如何運用創新性的視覺技術和不尋常的敘事結構來重新構架和重塑電影藝術本身的問題。

藝術來自於生活,電影也不例外,在1937年中日之間爆發戰爭,到後來的第二次世界大戰,都映射到電影作品當中,這段時期中的很多重要作品都與戰爭主題息息相關,其中1948年費穆的《小城之春》便是值得注意的一部。這部電影與以往的左派電影不同,它着重於探討和展現角色人物之前的矛盾衝突。1980年,中國電影檔案館為這部電影製作了新的拷貝,此片的重新發現立刻獲得了觀眾的追捧,並被香港電影獎評為最傑出的中國電影。

當在籌劃此次中國電影展播季的時候,我們發現在這一百年間,那些沒能呈現在大眾視野內的電影作品其數量並不比公演的電影來的少。考恩也在採訪中談到了1966年開始的“文革”是如何打亂了中國的文化和精神生活,而且這個特殊的歷史時期導致了中國電影發展特有的困境,電影和故事內容將受到審查,比如1975年的《決裂》,就被要求按照官方的要求進行敘事,不合適的人物形象也被要求重新塑造,電影不再是單純的娛樂項目,而是變成了官方政治宣傳的工具。1967至1972年,專題片電影的製作幾乎停止了,直到後來中國逐漸走出了“十年浩劫”的陰影,才出現了“傷痕電影”,這些誕生於文革前的電影人被稱作中國第四代電影人。

The season looked at key Hong Kong New Wave director Ann Hui’s film Boat People (1982), the last of her “Vietnam trilogy” recounting the plight of Vietnamese refugees after the communist takeover following the Fall of Saigon, and Edward Yang and Hou Hsiao-hsien’s work The Terroriser (1986) and A City of Sadness (1989). Together the pair put Taiwanese cinema on the international map with work that explored the island’s rapidly changing present as well as its turbulent, often bloody past with Yang’s The Terroriser a complex multi-narrative urban thriller that reflected the pressures and uncertainties of city life.

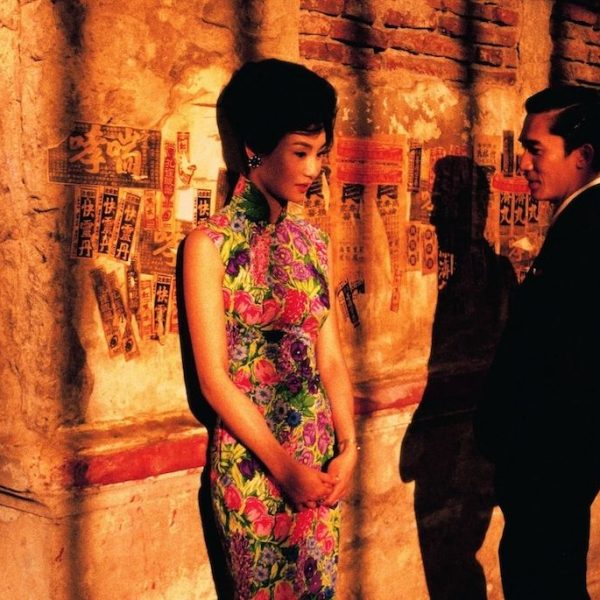

The ‘New Directions’ section of the BFI’s program looks at Chinese cinema’s most recent work: exciting and daring films made from 1993 to 2006 by acclaimed filmmakers such as Sixth Generation auteurs Jia Zhangke and Wang Xiaoshuai, Hong Kong Second Wave directors Wong Kar-wai and Stanley Kwan, and Taiwan’s Second New Wave filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang. Films by the Mainland’s directors Jia Zhangke and Wang Xiaoshuai reflect on marginalised individuals in contemporary urban and provincial life, and the negative impact of China’s social-economic changes. The Second Wave that appeared in the late 1980s in Hong Kong – led by Wong Kar-wai and Stanley Kwan – created lush, highly stylised films that introduced a powerful new aesthetic to international cinema. Wong’s offbeat, post-modern Chungking Express (1994) depicts urban loneliness and unrequited love.

在“新浪潮”這個部份,英國電影協會展現了中國大陸第四代電影人是如何努力來呈現特殊歷史時期中中國經歷的嚴酷環境,對於“傷痕電影”的闡釋也是借用了知名導演謝飛的一段問答。謝飛的電影放映同時也有相應的討論會,例如1990年的《本命年》,故事講述了姜文飾演的犯人刑滿釋放,他回到了從小生活的胡同,經歷了人間冷暖,後來愛上了一個歌廳歌手的故事,謝飛的作品為後來的第六代導演的傑出代表娄烨和贾樟柯開闢了道路──描繪和刻畫中國最充滿矛盾的那一面。放映中還包括了中國導演吳天明的最為重要的一部作品,完成于1986年的《老井》,這部作品也是對重塑中國電影形象極具建設作用的一部。

這次的演出季也特別關注了幾位重要的“新浪潮”香港導演和他們的作品,許鞍華導演1982年的《奔投怒海》是其“越南三部曲”的最後一部,講述了越南難民在西貢陷落後所處的困境。來自台灣的楊德昌1986年的《恐怖分子》和侯孝賢1989年的《悲情城市》,他們兩人的作品將台灣電影展現在國際屏幕之上,他們聚焦于台灣社會的劇烈變遷和動盪,楊德昌的《恐怖分子》更是展現了血腥的過往,紛繁複雜的城市生活,反映了當下社會人們承受的各種壓力和不確定的生活狀態。

So, what of Chinese cinema in the next one hundred years? Cowan muses that “In the near future, there’s going to be changes to funding structures and the government’s approach to filmmaking in the mainland as well as further changes in Hong Kong that are going to encourage more independent production”. So, will this mean a Chinese film industry that will retain its own sense of national identity or is there still a risk that Chinese filmmaking may become more Americanised or European? Cowan believes that “Chinese cinema has done a very good job at resisting outside influence, except when it wants it. Hong Kong could have just made Hollywood remakes and it would have been fine in terms of its local box office for 50 years [but] it chose to go down a different pathway”. In fact, in some instances it’s been the reverse: Chinese films have been remade by Hollywood, such as Andrew Lau and Alan Mak’s Infernal Affairs (2002), a thrilling story of an undercover cop and criminal infiltrating one another’s gangs, which would later be rebranded to an American audience as Martin Scorsese’s critically acclaimed The Departed (2006). So, if the present is anything to go by – and Cowan remarks that “the Chinese film-industry is on fire right now” – then the next one hundred years look fruitful for Chinese cinema.

在“新方向”單元,英國電影協會將目光投向了當下的中國電影作品,特別是1993年到2006年那些充滿大膽嘗試和令人興奮的電影作品,特別是中國第六代導演中的賈樟柯和王小帥;香港第二次浪潮導演王家衛和關錦鵬;台灣第二次新浪潮導演蔡明亮等都令人矚目。第二次浪潮出現在上世紀80年代末的香港,以王家衛和關錦鵬為代表的香港電影人開創了一個繁榮的,極具風格的電影流派,並將這種極富衝擊力的新電影美學展現在國際範疇之上。王家衛的電影很另類,充滿了後現代的文化特色,如1994年的《重慶森林》就是描繪了一個孤獨的城市故事和那不求回報的愛情故事。

那麼,未來中國電影的方向是在何方?考恩考慮了一下回答道:“在不遠的將來,中國電影的資金結構將會發生改變,大陸政府對待電影的態度和管理方式也會發生變化,香港將會更多地鼓勵獨立電影的生產。”這麼說來,中國電影將會繼續保持他獨特的中國特色,還是說中國電影產業也會有步上歐美電影產業雷同化的後塵?考恩相信:“中國電影產業在保持其獨立性方面做得非常好,香港在50年內其實都可以僅靠模仿好萊塢的電影就可以獲得不錯的本地票房,但他們選擇了走一條不一樣的道路。”事實上,很多情況下,這種狀況已經出現了反轉,一些中國電影已經被好萊塢翻拍并展現在大屏幕之上,比如劉偉強和麥兆輝2002年的《無間道》講述了一名臥底警察和警察團隊中內鬼之間發生的驚心動魄的故事,後來被翻拍為美國觀眾熟悉的,由馬丁·斯科塞斯主演的美國版《無間道(The Departed)》。對於如何評價當下的中國電影,考恩說到:“中國的電影產業,毫無疑問,當下正是在如火如荼一般的發展!”