23 June – 4 September 2016

Sainsbury Wing, National Gallery

。

“Works of art are models you are to imitate, and at the same time rivals you are to combat.” Sir Joshua Reynolds

This summer, the National Gallery explores great paintings from a unique perspective: from the point of view of the artists who owned them.

Spanning over five hundred years of art history, Painters’ Paintings presents more than eighty works, which were once in the possession of great painters: pictures that artists were given or chose to acquire, works they lived with and were inspired by. This is an exceptional opportunity to glimpse inside the private world of these painters and to understand the motivations of artists as collectors of paintings.

The inspiration for this exhibition is a painter’s painting: Corot’s Italian Woman, left to the nation by Lucian Freud following his death in 2011. Freud had bought the ‘Italian Woman’ 10 years earlier, no doubt drawn to its solid brushwork and intense physical presence. A major work in its own right, the painting demands to be considered in the light of Freud’s achievements, as a painter who tackled the representation of the human figure with vigour comparable to Corot’s.

In his will, Freud stated that he wanted to leave the painting to the nation as a thank you for welcoming his family so warmly when they arrived in the UK as refugees fleeing the Nazis. He also stipulated that the painting’s new home should be the National Gallery, where it could be enjoyed by future generations.

Anne Robbins, Curator of ‘Painters’ Paintings’ says:

“Since its acquisition the painting’s notable provenance has attracted considerable attention – in fact the picture is often appraised in the light of Freud’s own achievements, almost eclipsing the intrinsic merits of Corot’s canvas. It made us start considering questions such as which paintings do artists choose to hang on their own walls? How do the works of art they have in their homes and studios influence their personal creative journeys? What can we learn about painters from their collection of paintings? ‘Painters’ Paintings: From Freud to Van Dyck’ is the result.”

The National Gallery holds a number of important paintings which, like the Corot, once belonged to celebrated painters: Van Dyck’s Titian; Reynolds’s Rembrandt, and Matisse’s Degas among many others. ‘Painters’ Paintings’ is organised as a series of case studies each devoted to a particular painter-collector: Freud, Matisse, Degas, Leighton, Watts, Lawrence, Reynolds, and Van Dyck.

‘Painters’ Paintings’ explores the motivations of these artists – as patrons, rivals, speculators – to collect paintings. The exhibition looks at the significance of these works of art for the painters who owned them – as tokens of friendship, status symbols, models to emulate, cherished possessions, financial investments or sources of inspiration.

Works from these artists’ collections are juxtaposed with a number of their own paintings, highlighting the connections between their own creative production and the art they lived with. These pairings and confrontations shed new light on both the paintings and the creative process of the painters who owned them, creating a dynamic and original dialogue between possession and painterly creation.

Half the works in the exhibition are loans from public and private collections, from New York and Philadelphia to Copenhagen and Paris. A number of them have not been seen in public for several decades.

Dr Gabriele Finaldi, Director of the National Gallery says:

“Artists by definition live with their own pictures, but what motivates them to possess works by other painters, be they contemporaries – friends or rivals – or older masters? The exhibition looks for the answers in the collecting of Freud, Matisse, Degas, Leighton, Watts, Lawrence, Reynolds, and Van Dyck.”

Lucian Freud (1922–2011)

Lucian Freud’s work remains at the forefront of British figurative art. Fascinated by the tactile quality of paint, Freud had a lifelong fascination with the great painters of the past, and often visited museums and galleries, “I go and see pictures rather like going to the doctor. To get some help”, he said. At home, Freud surrounded himself with works of art he could admire in the flesh: paintings by 19th century French and British masters – Constable, Corot, Degas – each exuding their own unique energy. This room includes examples of these, such as Corot’s ‘Italian Woman’ (about 1870, The National Gallery, London), displayed here just as Freud showed it in his drawing room: between a small Degas bronze (‘Portrait of a Woman’, after 1918, Leeds Museums and Galleries (Leeds Art Gallery)), and a sketch sent to him by his friend Frank Auerbach as a birthday card (2002, Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge).

Freud’s attachment for the paintings he owned – here, a rarely seen Cézanne brothel scene (‘Afternoon in Naples’, 1876–77, Private Collection) and delightful Constable portrait (‘Laura Moubray’, 1808, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh) – is explored in his section, which also looks at the influence of these works on his own investigations into the human figure. The exhibition features Freud’s own striking ‘Self Portrait: Reflection’ (2002, Private Collection) and a nude portrait, ‘After Breakfast’ (2001, Private Collection).

Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

Matisse started acquiring pictures long before he had encountered success and could afford to do so; his collection also grew through gifts and exchanges with fellow artists. He famously swapped pictures with Picasso: he sent the Spanish artist a drawing in 1941 as a thank you for Picasso looking after his bank vault in occupied Paris.

Picasso responded with the majestic, spectacularly sombre ‘Portrait of Dora Maar’ (1942, Courtesy The Elkon Gallery, New York), sent to Matisse as a get-well present, after decades of a complicated friendship tinged with rivalry. A fine Signac (‘The Green House’, Venice, 1905, Private Collection) illustrates Matisse’s practice to swap works of art with painter friends, while an iconic work by Cézanne, ‘Three Bathers’ (1879–82, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris) shows how the pictures Matisse owned served his own art directly.

Having bought it in 1899 – then a great financial sacrifice – Matisse kept it for 37 years, during which, he said, he “came to know it fairly well, though [he] hoped, not entirely”. This painting and his Gauguin ‘Young Man with a Flower behind his Ear’ (1891, Property from a distinguished Private Collection – courtesy of Christie’s) informed Matisse’s own bold, simplified style, as his work was evolving towards a greater degree of abstraction, evident in his spectacular sculpture ‘Back III’ (1916–17, Centre Pompidou, Mnam/Cci, Paris), borrowing from his Cézanne. We know tantalisingly little about the circumstances surrounding Matisse’s purchase of Degas’s Combing the Hair (about 1896, The National Gallery, London) yet the painting can be viewed from the vantage point of Matisse’s own work, rich in such scenes – as reflected in his ‘The Inattentive Reader’ (1919, Tate).

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

A supreme master of technique and unrivalled experimentalist, Degas was an astute observer of modern life, yet his art remained embedded in tradition. He was also one of the greatest collectors of his time. “Degas carries on…buying, buying: in the evening he asks himself how he will pay for what he bought that day, and the next morning he starts again…” a friend wrote in 1896. Degas often traded his own paintings or pastels against the pieces he coveted most (Manet, ‘Woman with a Cat’, 1880–2, Tate). He acquired a wide range of works, from Old Masters paintings to pictures by artists considered, at that time, avant-garde, such as Cézanne’s’ Bather with Outstretched Arm’ (1883–85, Collection Jasper Johns).

Degas collected the work of Manet, doggedly tracking down the dispersed sections of The Execution of Maximilian (about 1867–8, The National Gallery, London) after the death of his friend. He purchased great numbers of works of art by his heroes Ingres (Oedipus and the Sphinx, about 1826, and Angelica saved by Ruggiero, 1819–39, both National Gallery, London) and Delacroix (‘Hercules rescuing Hesione’, 1852, Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen and ‘Study of the Sky at Sunset’, 1849–50, The British Museum, London), focussing his attention on paintings which held a particular emotional significance for him and collecting those works as an act of homage. He also supported struggling artists – Gauguin, Sisley – by buying their works (Sisley, ‘The Flood. Banks of the Seine’, Bougival, 1873, Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen), providing them with much-needed financial support.

Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830–1896) and George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

One of the most renowned painters and sculptors of the Victorian era, and the leading figure of its art establishment, Leighton was aware of the power of art to convey social prestige and guarantee professional progress. He displayed in his sumptuous Holland Park studio-house the magnificent ensemble of pictures and objects he had purchased. Among them were Italian Renaissance paintings which showed his refined taste (Possibly by Jacopo Tintoretto, Jupiter and Semele, about 1545, The National Gallery, London) but also mid-19th century. French landscapes alluding to his continental training.

Corot’s Four Times of Day (about 1858, The National Gallery, London) formed the centrepiece of his drawing room, an enlightened choice showing Leighton’s advanced appreciation of French landscape painters. There, the Corot panels served as a source of inspiration as much as interior decoration, resonating with Leighton’s own landscapes, arguably the most individual part of his artistic production (‘Aynhoe Park’, 1860s, and ‘Trees at Cliveden’, 1880s, both Private Collection).

The painter George Frederic Watts, Leighton’s friend, neighbour, and regular visitor to his house, would have been impressed by the vast array of pictures in Leighton’s collection. The two artists shared a love for Italy and a desire to belong to the great artistic tradition reaching back to the Renaissance; in his ‘Self Portrait in a Red Robe’ (about 1853, Watts Gallery) he depicted himself in the robes of a Venetian senator. Determined to make art accessible to all, Watts gave the few paintings he owned to public galleries – not least the imposing Knight of S. Stefano(probably Girolamo Macchietti, after 1563, The National Gallery, London).

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

Lawrence was the leading British portraitist of the early 19th century. He was largely self-taught and hugely influenced by Sir Joshua Reynolds, following in his footsteps to become President of the Royal Academy. Like Degas, Lawrence was a voracious, obsessional collector, using the proceeds of the sale of his society portraits to amass an incomparable collection of Old Master drawings – an inventory upon his death listed some 4,300 drawings, including Carracci’s immenseA Woman borne off by a Sea God (?) (about 1599, The National Gallery, London) and a number of paintings including Raphael’s Allegry (about 1504, The National Gallery, London) and Reni’s Coronation of the Virgin, (about 1607, The National Gallery, London).

This section of the exhibition places Lawrence’s collecting within his social world. The paintings he acquired established his reputation as a great connoisseur; his advice was much sought by influential friends such as John Julius Angerstein and Sir George Beaumont, whose collections came to form the nucleus of the National Gallery holdings. Beyond his acquisitive zeal, the prodigiously gifted Lawrence also sought to gain information about his favoured artists’ methods. An exceptional loan from a private collection, his portrait of the Baring Brothers (Lawrence, ‘Sir Francis Baring, 1st Baronet, John Baring and Charles Wall’, 1806–07) demonstrates his absorption of the tradition of Renaissance male portrait, here injected with Lawrence’s trademark dash and virtuosity.

Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

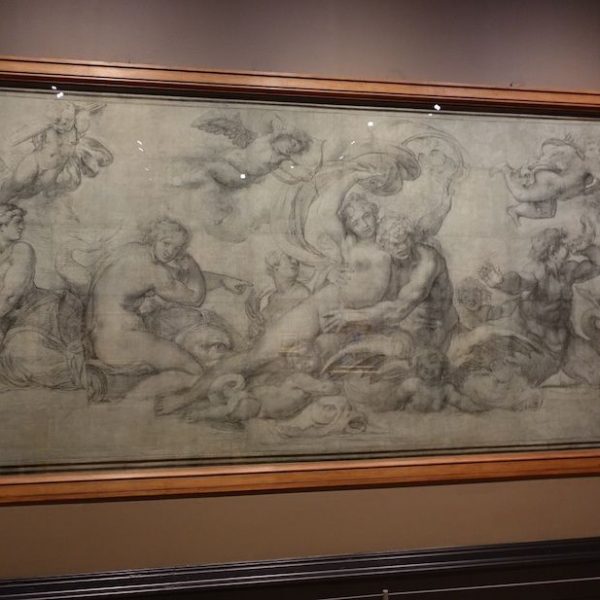

As the inaugural President of the Royal Academy, Reynolds was one of the most significant figures of the British art world in the 18th century; for him, collecting was a life-long passion, which he likened to “a great game”. Reynolds had a vast collection of drawings, paintings and prints that informed both his teachings and supported his ideas about what constituted great art – style of Van Dyck (The Horses of Achilles, 1635–45, The National Gallery, London), Giovanni Bellini (The Agony in the Garden, about 1465, The National Gallery, London), after Michelangelo (Leda and the Swan, after 1530, The National Gallery, London), Poussin (The Adoration of the Shepherds, about 1633–4, The National Gallery, London) and Rembrandt (The Lamentation over the Dead Christ, about 1634–35, The British Museum, London).

Gainsborough’s ‘Girl with Pigs’ (1781–2, Castle Howard Collection), bought by Reynolds in 1782, also illustrates Reynold’s interest for the work of his contemporaries, demonstrating the breadth of his taste, but also its changeability – soon after, Reynolds tried to exchange his Gainsborough for a Titian.

Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Van Dyck was England’s leading court painter in the first half of the 17th century. Before enjoying success, he worked in the studio of Rubens, himself a great collector; following his master’s example, Van Dyck would soon acquire his own impressive array of Italian pictures. While he owned paintings by Raphael and Tintoretto, Van Dyck was almost single-minded in his passion for the work of Titian. Inventories made on the artist’s death list 19 works by Titian, most of which were portraits, including the Vendramin Family (1540–5, The National Gallery, London) and Portrait of Gerolamo (?) Barbarigo (about 1510, The National Gallery, London).

This room focuses on Van Dyck as collector, through his intense interest for the work of Titian, to whom he may owe his ingenious compositional devices (Lord John Stuart and His Brother, Lord Bernard Stuart, about 1638, The National Gallery, London) and technical freedom (‘Thomas Killigrew and William, Lord Crofts (?)’, 1638, The Royal Collection/HM Queen Elizabeth II). The resonance between Titian’s and Van Dyck’s depictions of figures is just one of the stories to be explored within this final section of the exhibition.