Alexandra Baraitser and YU Xiao

She Paints Still

3 Sep -4 Oct 2025

Tiderip x Mandy Zhang Art

London

She Paints Still is a dual-venue exhibition initiated by two Chinese female gallerists based in London. It focuses on the sustained painting practices of women artists navigating different life stages, cultural contexts, and artistic languages. Presented concurrently at Tiderip and Mandy Zhang Art, the exhibition features works by British artist Alexandra Baraitser and Chinese artist Yu Xiao, drawing from various series and time periods. It highlights both the conceptual and formal divergences between their practices while constructing a cross-temporal visual dialogue through spatial juxtaposition.

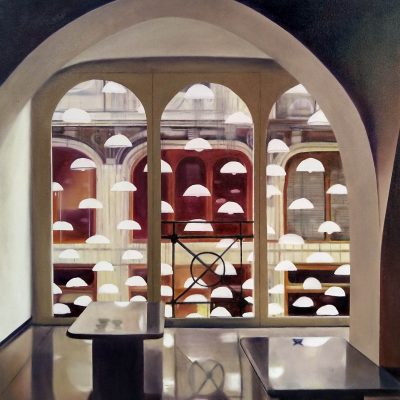

At Tiderip, Baraitser’s early paintings are on view—meticulous renderings inspired by iconic designers such as Mackintosh, Eames, and Poul Henningsen. These works focus on reimagining classic furniture and interiors, revealing her refined understanding of structure and order. Alongside them are Yu Xiao’s installation and her Da Vinci Mirror series, which meditates on perception, perspective, and the intersection of abstraction and reality. Referencing Leonardo da Vinci, the series pairs precise geometric structures with irregular fabric folds, metaphorically addressing the tension between expectations and concealed emotional depth. The formal and structural interplay between the two artists’ works opens a space of dual inquiry: into order, and its disruption.

The Mandy Zhang Art space centres on more recent works by both artists. Baraitser shifts her focus from individual design objects to broader “modernist spaces”—lobbies, courtyards, and building façades—employing an external gaze to translate interior space, creating a detached yet introspective mode of looking. In contrast, Yu Xiao’s Utopian Blink series explores the tension between idealism and reality through geometric compositions and vibrant color fields. Her works evoke moments of brief yet intense visual awakening, prompting a renewed perception of time and space.

Through this interwoven arrangement of spaces and series, She Paints Still invites audiences to consider how female artistic practice endures through persistence in the face of cultural and structural challenges, the multiplicity of cross-cultural identities, and the temporal flows embedded in artistic production. The exhibition challenges the idea of interruption, showing how female artists sustain painting as a vital and enduring form of expression amid shifting lives and cultural contexts.

《她,繪如既往(She Paints Still)》是由兩位活躍於倫敦的中國女性畫廊主發起的一場雙空間展覽,聚焦女性藝術家在不同生命階段、文化背景與創作語言中的持續繪畫實踐。展覽於 Tiderip 與 Mandy Zhang Art 兩個空間同期呈現英國藝術家 Alexandra Baraitser 與中國藝術家余曉來自不同系列與時期的作品,既凸顯其觀念與形式上的差異,也通過空間的交錯佈局構建出一場跨時空的視覺對話。

Tiderip 空間展出了 Baraitser 的早期繪畫系列——以 Mackintosh、Eames、Poul Henningsen 等國際設計師為靈感,聚焦經典傢具與室內空間的再現,展現她對設計結構的細膩重構與秩序化理解。該空間亦呈現余曉的裝置作品與「Da Vinci Mirror」系列,此系列以嚴謹的幾何結構與不規則布料褶皺並置,構成對感知、視角與現實之間張力的沈思性回應。標題向達·芬奇致敬,同時隱喻理性預期下的複雜現實與隱藏情感。兩組作品在結構與形式上的呼應,共同指向對「秩序」與「破壞」的雙重探討。

Mandy Zhang Art 空間則聚焦於兩位藝術家的近期創作。Baraitser 的新作由早期對單一設計對象的描繪轉向對「現代主義空間」的整體考察,作品涵蓋酒店大堂、庭院與建築立面等場域,並通過從外部觀看內部的方式,營造出一種抽離而內省的觀看關係。與此同時,余曉呈現的「Utopian Blink」系列,則以幾何構成與色彩交織,探討理想與現實之間的心理張力。作品如同一次短促卻深刻的觀看閃現,引導觀者重新感知時間與空間的流動性。

透過這次展覽在兩個空間與不同系列之間的交織安排,《她,繪如既往》 邀請觀眾思考:在面對文化與結構性的挑戰時,女性藝術家如何以堅持不懈的創作實踐,讓繪畫得以延續;又如何在多重的跨文化身份中找到自我定位,並回應藝術創作所內含的時間流動與轉變。展覽挑戰了「創作中斷」的常見想像,呈現出在生命經歷與文化語境不斷變化之下,繪畫如何成為女性藝術家持續表達自身、回應世界的一種有力方式。

Alexandra Baraitser: On Structure, Distance, and Modernist Space

專訪 Alexandra Baraitser|結構與距離:在空間中觀看現代主義

AZ:Your early works, such as Ladies Armchair and A Testament to Life, revisit classic design objects with a meticulous, almost reverent precision. What first drew you to mid-century interiors and Bauhaus design as subjects for painting?

AB:On my MA course at Chelsea, I had been painting large cactus paintings and one day I was looking at this painting and I thought it reminded me of a battered old sofa. So the following week I started making these paintings of chairs and loungers that I had found in pictures from furniture sales catalogues. After a few years I started to look more closely at classic designs that I admired and always wanted to own, such as the ones my parents collected by Mies Van Der Rohe (the Barcelona Chair), and I felt a personal connection to them. Once painted, these objects were transformed into icons which was exciting for me.

AZ: Many of your paintings capture interiors without people, such as hotel lobbies, chairs, or lamps. What role does this absence play in your work?

AB:Without the figure things appear empty and everything is still and tranquil. My work is suggestive of liminal experiences, emotions and memories – a corridor or room without people transports you to that sort of environment. It’s also to do with the places we inhabit that are built structures which are intensively designed, and which suggest a human presence, and that’s what captures my attention, the focus is intended to be on the formality of the everyday objects and buildings. Occasionally a figure is introduced but it is a more ambiguous and looser element.

AZ: In your process you often begin with magazine clippings and photographs, building up glossy, translucent surfaces in thin oil layers. Your work has roots in photorealism, though it has evolved over time. Could you walk us through how this translation from source material into painting unfolds in the studio?

AB:I spend a lot of time in the studio looking through pictures that I have archived. Some of the photos are my own and some are sourced from catalogues, books, newspaper clippings or design magazines. I rephotograph the originals on my phone camera and once they are downloaded I manipulate them, adding colour or removing objects and areas I don’t like. After editing, it is then worked on in the studio with the aim of bringing the image to the edge of abstraction. However, sometimes I will be inspired to paint from a photo, (that wasn’t taken by me), in a more hyper-real way that is a tribute to the photographer and their wonderful image and an attempt to reinvent something using my own language. They are my interpretation rather than a copy.

AZ: In She Paints Still we encounter paintings from different periods of your practice, yet they feel deeply connected. What shifts in focus or approach mark the evolution of your style, and how do you see the relationship between these bodies of work?

AB:When I was at The British School at Rome in 1997, I was inspired by Roman urns and sculptural objects that I found in the landscape of the city. The slower pace of life at The British School at Rome meant I could allow myself to indulge in new ideas and to spend more time absorbing frescos and 17th and 18th century paintings. On my return to London, the shift to ‘chairs’ from semi-abstract ‘Roman urns’ and ‘cactuses’ seemed to me to be an unusual leap, but the two styles are connected. Being back in the UK and enjoying London’s beautiful iconic designs, led to a shift in focus, and an interest in more modern, structured and designed forms such as bridges, buildings, and furniture. This was an important stage, one that led to my current style. Since then my work has continued to evolve and has over the years shifted from photorealism to a more abstract form of expression, with fluid brush strokes emphasising the contrast of light and shade.

AZ:In She Paints Still your work is shown in dialogue with Yu Xiao’s across two London galleries. How does this dual-venue presentation amplify the reading of your work?

AB:In She Paints Still, the viewer is reminded of upholstery, history of design, furniture construction. The show highlights an interest in structure and how we can relook at construction and built forms in new ways. In my work, I am trying to get away from built structure, freeing up the object. As contemporary still lives, these are objects or modernist environments that I understand as intensively ‘designed’, often in quite formal ways, which holds my interest. Yet through saturated colour, or flattening and by pulling them apart, my aim is to free these objects from what constrains them. The connection between our work has helped me to recognise this.

AZ: Your career began in the mid-1990s with early recognition through the Abbey Scholarship and the John Moores Prize. There was also a long pause in your practice when motherhood and life outside the studio took precedence. How do you look back on that period now, and how has it shaped the resilience and perspective you bring to painting today?

AB:I do look back and think how lucky I was to have those breaks so early in my career. I was also really young and had a lot of energy then. There were gaps in my career when nothing was really happening, and I didn’t have a studio, (such as during Covid and when my children were really small), and that sort of break was hard for me but I didn’t give up hope. I never believed I wouldn’t get there, I just kept going – it’s what I do. So, even though I slowed down and didn’t paint as much as I used to, I still had ideas and as soon as I had time to send out images to galleries I did. However this time with more determination, because life is short and I was aware of my age when I reemerged and I felt that my work was stronger than ever!

A Testament To Life No. 1 by Alexandra Baraitser

AZ:你的早期作品,例如《Ladies Armchair》和《A Testament to Life》,以極為精細、近乎敬畏的筆觸重訪經典設計。最初是什麼吸引你將上世紀中期的室內和包豪斯設計作為你的繪畫題材?

AB:我在倫敦切爾西藝術學院攻讀碩士時曾創作了很多以大型仙人掌為題材的作品。有一天,在我端詳其中一幅的時候,它讓我突然回想起了一張破舊的老沙發。於是,我開始以傢具展銷冊中的圖像作為靈感,創作了一系列椅子與躺椅的畫作。幾年後,我開始更關注一些我欣賞並一直想擁有的經典設計,其中包括了我父母收藏了的密斯·凡·德·羅的傢具(如巴塞羅那椅),使我感受到一種私人的聯結。通過繪畫,這些物件轉化為另一種符號形象,這個過程對我來說非常有意思。

AZ:你的許多作品描繪了人物缺席的室內場景,例如酒店大堂、椅子或燈具。這種「不在場」在你的作品中起到什麼作用?

AB:人物缺席時,空間顯得空曠,一切都靜止而寧靜。我的作品常暗示著一種臨界的體驗、情感與記憶——一條沒有人的走廊或房間,會將觀者帶入這種氛圍。它也與我們所居住的建築空間有關,這些空間經過精心設計,暗示了人的存在,這正是它們吸引的地方。我希望觀者的焦點更集中在日常物件和建築的形式感上。偶爾,我會加入人物,但通常是以更為模糊而非具象的形式。

AZ:在創作過程中,你經常從雜誌剪貼和照片入手,再通過薄薄的油彩層疊出光滑、半透明的表面。你的作品最初受到照相寫實主義的影響,但隨著時間逐漸演變。你能分享一下這種從素材到繪畫的轉化過程嗎?

AB:我在工作室里經常花很多時間翻看自己收集的圖片資料。有些是我自己拍的照片,有些圖片則來自目錄、書籍、報紙或者設計雜誌。我會用手機重新拍這些圖,再下載到電腦里進行處理,比如調整顏色或者刪掉我不喜歡的部分。完成編輯後,我會把它們作為基礎帶進工作室里畫,目標是把這些圖像推近抽象的邊緣。不過,有時候我也會被別人的照片直接打動去畫,用一種更加超真實的方式來畫,是向攝影師和他們創造的精彩畫面致敬,同時用我自己的繪畫語言去重新詮釋。這些畫是我的個人解讀,而不是復刻。

AZ:在《她,繪如既往》中,我們看到了你不同時期的作品,但它們之間依然保持著緊密的聯繫。你如何看待自己繪畫風格的變化?這些作品之間的關係又是怎樣的?

AB:1997年我在羅馬英國學院時,被當地看到的羅馬陶罐和雕塑深深吸引。羅馬的節奏更慢,讓我有機會沈浸在壁畫以及17、18世紀的繪畫中。回到倫敦後,我從半抽象的「羅馬陶罐」和「仙人掌」轉向「椅子」,乍一看跨度很大,但其實兩者是有聯繫的。在英國,我被現代主義設計、橋梁、建築、傢具這些精緻的結構所吸引,這個階段對我形成現在的風格非常關鍵。之後這些年,我的作品從照相寫實主義逐漸發展為更抽象的表達,筆觸更自由流動,更突出光影的對比。

AZ:在《她,繪如既往》中,你的作品與余曉的作品在兩家倫敦畫廊中同時展出。這樣的雙會場呈現如何影響觀眾對你作品的理解?

AB:在《她,繪如既往》中,觀眾會注意到我作品中反復出現的元素,比如軟墊、傢具結構,以及設計歷史。展覽重點突出了我們對「結構」的共同興趣,以及我們該如何重新理解建立和構造。在我的繪畫里,我嘗試擺脫這些已經被建立的結構,把它們解放出來。它們作為當代的「靜物」,是我理解中經過高度設計過的物件或現代環境,常以非常形式的方式存在,是我一直以來的興趣。但我會用飽和的色彩、平面化的處理和拆解的方式,意圖釋放它們的限制。和余曉的作品同場出現,也讓我重新意識到自己在這方面的探索。

AZ:你的藝術生涯始於上世紀90年代中期,很早就獲得了Abbey獎學金和John Moores繪畫獎的認可。但中間也有很長一段停頓,因為成為兩個孩子的母親而離開工作室,照顧家庭變成了人生的優先。你現在回頭看那段經歷,它如何塑造了你今天的韌性和視角?

AB:回頭看,我覺得很幸運在職業初期就有那樣的機會。當時我年輕,精力也很充沛。但確實有一些階段,我的創作幾乎停滯,比如孩子小時候,或者新冠疫情期間沒有工作室,那段時間對我來說挺艱難的。不過我從來沒有放棄過希望,也從沒想過自己會徹底停止。我始終覺得自己會堅持下去——因為這就是我該做的事。雖然那時的產出比以前少,但我腦子里始終有新的想法。一旦條件允許,我就會把新作品拍攝下來發給畫廊。而這次的展覽我更有決心了,因為我清楚時間有限,也更明白自己的作品比以往更成熟、更有力量。

A Testament To Life No. 2 by Alexandra Baraitser

Yu Xiao: Silence in Fracture — Shame, the Body, and Painting

專訪余曉|裂變中的靜默:羞恥、身體與繪畫

AZ:How would you describe the core focus of your work and your approach to painting?

YX:I have been always asking myself the question of how to redirect the complex dynamics of the female experience, such as shame, stigma, or pain of something, without exposing the exact figurative wound-related narrative, or evident against masculine image.

I explore the translation of the cost of silence into material echo, focusing on the female body and experiences of often overlooked marginalised vulnerabilities in patriarchal societies.. such as stigma of involuntary early menopause, or gender discrimination -related psychological trauma, unutterable physical suffering. I treat painting as a living body, not just painting about something, instead, experiencing something. So that cuttings as brushstroke, you don’t see the moves of the cut, but you can feel it.

My approach begins with rupture: cutting, folding, and reconfiguring canvases to reveal what painting usually conceals. Raw edges and stretcher bars become archives of mourning, turning shame into generative material. I combine psychoanalytic and postmodern ideas with traditional Chinese aesthetics—Song Dynasty principles of qi and xu—while using material gestures like masking tape balls or red dots to transform private trauma into tangible, visual forms. Painting becomes a site where bodily experience and materiality meet, mourn, and reconfigure freedom.

AZ:Could you tell us about the works you are presenting in She Paints Still?

YX:In She Paints Still, I present two series that rethink the Figural of Mark-Making, Cutting, and Trans-encounter, in the Moment of shifting out of female experience. I want viewers to gain the sense of tearing off the beautiful skin, evoke empathy and joyfulness of rejuvenation, making as thinking, and create affective assemblages.

Utopia Blink investigates the idea of a “non-place,” Perhaps, a realm of potential beyond tangible reality. The act of blinking becomes both lens and spark—a way of seeing that jolts attention and opens new avenues of creation. Assemblage allows me to explore how fleeting insight and materiality can converge in unexpected ways.

Da Vinci’s Mirror is a quiet meditation on perception and perspective, shaped in part by Helene Cixous’s concept of écriture féminine. The images remain fluid, refusing to fix, and trace the unspoken currents of female experience.

Across both series, canvases breathe as living entities. Surgical cuts expose raw linen; frames and stretchers carry unseen spaces; masking tape balls tuck secrets. The work embodies a trans-cultural dialogue where Song Dynasty xu meets Lyotard’s “unpresentable,” elevating materials usually hidden into active, expressive participants in the painting.

The work is like a game sometimes, beyond time and space. For example this site specific installation Monad Loop gaming, it is the way to tribute the French art movement Support/Surface in the 60s, in contemporary fashion. Seeming deconstruction is reassembling, and the game of a living asymmetry.

AZ:What distinguishes your work from other contemporary artists?

YX:Three defining features shape my practice:

Materialisation of affect: I translate psychological mourning into visual symbols—balls as ovarian metaphors, cuts as wounds—creating an autonomous, self-sustaining form of painting. I embed Song aesthetics in the canvas, generating a dialogue with Lyotard’s idea of “the unpresentable in presentation itself.”

A feminist approach to shame: Rather than depicting biographical trauma, I transform it into material encounters. Stretchers, voids, and masking tape balls become extensions of the body, abstracting experience into a shared, tangible form.

Challenging painterly hierarchies: Cutting and folding activate hidden narratives in canvases and stretchers. These gestures are reparative rather than destructive, echoing Taoist ideas of transformation: from rupture comes wholeness. Mourning becomes a revolutionary act, and the materials themselves carry meaning—stretchers as skin, voids as chorus, and balls as ovaries.

AZ:What challenges do you face as a full-time artist, and what keeps your practice alive?

YX:Challenges always lie ahead, not behind. I focus on moving forward, learning from each experience while remaining aware that obstacles are never absent. This process continuously refreshes my perception, enhancing artistic sensitivity and keeping the work vibrant.

Motivation comes from both play and process. For example, the Dot Conspiracy—tiny red dots on gallery price tags—feels like a network of mischievous agents. They animate the paintings, interacting with masking tape balls and sparking delight. Creating always produces unexpected energy, and my studio amplifies this: a space full of emotional resonance, inviting complete immersion and curiosity.

AZ:What are your future ambitions, and what new directions do you hope to explore?

YX:I let my practice guide the goals that emerge, asking how artistic and literary discoveries can integrate into my painting model and how narratives can evolve without essentialism.

I hope to create immersive installations, such as a Transcultural Womb, where paintings leave the wall entirely, and galleries become spaces of ritualised silence, as in “Shame is Quiet Nature.” These projects allow me to expand a feminist approach to reversing shame, blending elegance with resistance. My ongoing work continues to explore how silence, materiality, and form can intersect to produce a transformative experience.

AZ:How do you envision the evolution of your work in the coming years?

YX:I see my work increasingly blurring boundaries—East and West, body and material, trauma and beauty. I aim to deepen the dialogue between philosophical ideas and embodied experience, exploring how painting can act as a living presence.

Future projects will likely expand into immersive, spatial formats where viewers inhabit the work rather than simply observe it. I remain committed to pushing painting’s limits, turning private experience into collective encounter, and using rupture, materiality, and feminist thought to create spaces for reflection, empathy, and renewal.

Da Vinci’s Mirror No. 160.01/10 (2024) by YU Xiao

AZ:你如何描述自己創作的核心關注點與繪畫方法?

YX:我一直在思考這樣一個問題:如何在不直接暴露具象傷口、不以明顯的對抗姿態對抗男性圖像的情況下,重新引導女性經驗中複雜的動態,例如羞恥、烙印或疼痛。

我嘗試把沈默的代價轉化為物質的回響,聚焦於父權社會中,女性身體以及那些常被忽視的邊緣化脆弱經驗,例如: 非自願的早發性更年期污名化,性別歧視相關心理創傷,無法言說的身體痛楚。在我看來,繪畫並非「關於某物」,而是作為一個「活的身體」,是親身經歷本身。於是,切割成為一種筆觸:你或許看不到刀痕的動作,卻能感受到它的存在。

我的方法始於「破裂」:切割、折疊與重構畫布,揭示繪畫通常所隱匿的部分。裸露的邊緣與畫框成為哀悼的檔案,將羞恥轉化為生成性的材料。我將精神分析與後現代思想與中國傳統美學——宋代的「氣」與「虛」——並置,同時通過諸如膠帶紙團或紅點這樣的物質動作,將私密的創傷轉譯為具象的視覺形式。繪畫因此成為身體經驗與物質性交匯的場域,在此哀悼、重構,並重新想象自由。

AZ:你能否介紹一下此次在《她,繪如既往》中展出的作品?

YX:在《她,繪如既往》中,我呈現了兩個系列,重新思考「圖像性」與「痕跡」的關係——切割、交錯、相遇——在從女性經驗中轉出的瞬間,營造出感性聚合。我希望觀者能感受到撕開美麗表皮的那一刻,喚起共情,以及煥新的喜悅。創作即是經歷,正是在「做」的過程中生成情感的聯結。

《Utopia Blink》探討了「非場所」的概念,那或許是一種超越現實的潛能之境。「眨眼」在此既是透鏡,也是火花——一種喚醒注意力並開啓創作新路徑的觀看方式。通過拼貼與重組,我探索瞬間洞見與物質性如何在意想不到的方式中交匯。

《Da Vinci’s Mirror》則是一種靜謐的冥想,關於感知與視角,部分受到埃萊娜·西蘇的「女性書寫」概念的啓發。圖像保持流動,拒絕凝固,試圖描摹女性經驗中未被言說的暗流。

在這兩個系列中,畫布猶如呼吸的生命體。精准的切口裸露出粗糲的麻布,畫框與畫架承載著未被看見的空間,膠帶紙團包裹著隱秘。作品構成一種跨文化的對話,在其中,宋代「虛」的美學與利奧塔所說的「不可呈現之物」相遇。那些通常被隱藏的材料被提升為繪畫的主動參與者與表達者。

這些作品有時也像是一種遊戲,超越時空。比如場域特定裝置《Monad Loop gaming》,就是以當代方式向 20 世紀 60 年代法國「支持/表面」藝術運動致敬。看似解構,其實是另一種重組;一種關於「活的不對稱」的遊戲。

AZ:你的作品相比其他當代藝術家,有哪些獨特之處?

YX:我的創作主要有三大特點:

情感物質化: 我將哀悼的心理機制轉化為視覺符號——膠帶球象徵卵巢,切口象徵傷口——創造出自足的繪畫形式。我將宋代美學嵌入畫布肌理中,形成利奧塔所說的「呈現中的不可呈現」的對話。

女性主義視角下的羞恥重塑: 我通過具象繪畫將創傷抽象為物質性體驗,而非直接呈現個人經歷。畫架、空白與膠帶球成為身體的延伸。作品超越個人傳記性痛苦,將親密的創傷轉化為可共享的物質形態。

顛覆繪畫等級結構: 切割與折疊激活畫布背面和畫架的敘事潛能。這些動作非破壞性,而是修復性,呼應道家「由裂變而圓滿」的理念。哀悼成為革命性的行為:畫架是皮膚,空白是合唱,膠帶球是卵巢。

AZ:作為全職藝術家,你面臨的最大挑戰是什麼?是什麼讓你保持創作動力?

YX:挑戰總在未來,而非過去。我會忘記已克服的困難,專注於前行,並始終意識到挑戰永遠存在。這一過程不斷刷新我的感知,提升藝術敏感性,讓創作始終保持活力。

激勵我創作的事物有很多。比如《紅點陰謀》:畫廊標籤上的小紅點像叛逆的特工,它們讓作品生動起來,與膠帶球互動,徬彿低語著「這顆膠帶球竟然這麼貴?!」創作總會產生意想不到的火花,激發好奇心與創作能量。我的工作室也充滿魔力般的氛圍,散髮豐富的情緒能量,一旦進入,便令人全身心投入,無法自拔。

AZ:作為藝術家,你未來有什麼目標?目前對哪些主題或材料感興趣?

YX:我的目標隨創作過程自然展開,探索藝術與文學發現如何融入呈現性組合,以及繪畫模型如何演變,敘事如何在不陷入本質主義的情況下前行。

我希望創作沈浸式裝置,例如 《Transcultural Womb》,讓作品完全脫離牆面;另一個項目設想將畫廊變為儀式化的沉默空間,名為 《Shame is Quiet Nature》。這些項目旨在拓展通過具象繪畫逆轉羞恥的女性主義實踐。我的持續工作仍專注於以優雅的力量與溫柔的抵抗傳達沈默,使材料與形式相遇,創造變革性的體驗。

AZ:你如何看待未來幾年自己作品的發展方向?

YX:我希望作品進一步模糊界限——東西方、身體與材料、創傷與美感。我計劃深化哲學理念與身體經驗之間的對話,探索繪畫作為有生命存在的可能性。

未來,我的創作可能會擴展至沉浸式空間,讓觀者置身其中而非僅僅觀看。我將持續推動繪畫邊界,將私人經驗轉化為集體體驗,並通過裂變、材料性與女性主義思想,創造反思、共情與更新的空間。

Da Vinci’s Mirror No.105.08/22 (2025) by YU Xiao

在《她,繪如既往》中,Alexandra Baraitser 與余曉的作品不僅展現了形式語言與文化語境上的差異,也在結構、觀看與材料性等層面形成複雜的呼應。Baraitser 以秩序、結構與觀看的距離感,建構出一種現代主義繪畫語言;而余曉則透過身體經驗、羞恥與切割,將私人記憶轉化為共感的場域。

儘管生命階段不同、媒介處理各異,她們的作品都拒絕被「中斷」定義,而是以各自方式回應時代、回應自身,並不斷重新發明繪畫作為語言與存在的可能性。

Photography by ZimplePlus Studio

Text by Marjorier Ding