Dr. Joel Anderson has taught at Central School of Speech and Drama in London since 2007. His doctoral studies were undertaken at the Université Paris VIII and Queen Mary, University of London. He has worked extensively with the Paris Theatre of the Oppressed, including projects in Brazil, Burundi, and Morocco, and a current project in Jordan. Recent research includes an examination of the relationships between theatre and the photographic image and work on the urban environment.

喬爾·安德森博士從2007年以來開始在倫 敦中央演講與戲劇學院任教,他曾在巴黎 第八大學、瑪麗皇後學院、倫敦大學等地 進行博士後研究。他曾經在法國、巴西、布 隆迪、約旦以及摩洛哥從事劇場相關的研 究項目。安德森博士目前關注的領域是考 量劇場與攝影圖像及城市環境之間的關 係和相互影響。

ART.ZIP: How did you begin the study of theatre photography? What topics are you specially interested in?

JA: I first got fascinated with theatre photography when I realised the wide range of different practices that can come under this heading. I have been interested in theatre and in photography for most of my life. I recall that it was during a visit to the National Media Museum (in those days called the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television), in Bradford, that I started to think about the ways in which some of the notions we associate with photography (posing, staging, etc.) come from theatre.

ART.ZIP:你最初是怎樣開始從事戲劇攝影工作的?有沒有特別 感興趣的題材?

JA:我對戲劇攝影產生興趣,是因為了解到這一領域內容豐富 多樣。我一直很喜歡戲劇和攝影。記得有一次去布拉德福德參觀 國家傳媒博物館(當時叫國家攝影電影電視博物館),我開始意 識到,攝影中的姿勢擺造、佈景等概念都是來源於戲劇。

ART.ZIP: Could you tell us more about theatre photography? Its history, development, status quo, and trend in the future?

JA: It is a very vague term, really, and there are lots of very different practices that might be called ‘theatre photography’. The earliest theatre photographs come very early in the history of photography, and were studio portraits of actors, which were – in a sense – merely examples of the genre of the civic portrait (with actors among those professionals being the subject of a photograph, showing them in their role complete with tools of the trade). But actor portraits progressively incorporated elements from plays: scenery, costumes, props. Actors were thus shown playing a role, although not always a role they themselves had ever played in the theatre. Photographs were not take on the theatre stage until the late 19th Century. In the early 20th Century, a convention, which still exists today, was to photograph actors holding still poses, individually or in groups – a kind of secondary staging of the play, for the benefit of the photographer. In her book, which remains one of the only volumes about theatre photography Chantal Meyer- Plantureux describes how this practice of the photo-call would sometimes produce two identical images, but taken by different photographers working for different agencies. The photo-call was, of course, a necessity for a photographer seeking to make a clear and coherent image – the photosensitive materials and lenses of the time were not able to ‘freeze’ action, especially in the darkness of a theatre. But the practice should also be understood ideologically, as corresponding to what kinds of image were required at a certain point and in a certain society.

ART.ZIP:能否多介紹一下戲劇攝影?比如它的歷史、發展、現狀 以及未來趨勢等等?

JA:戲劇攝影其實是個比較模糊的概念,它涵蓋的形式非常廣 泛。最早的戲劇攝影作品是在攝影發展初級階段就已出現,即演 員的工作室肖像照,屬於公民肖像的一種。圖片的主題為戲劇演 員,他們與其他工作人員一起出現在照片中,並配上相應的道具 來完整地顯示他們扮演的角色。演員肖像照漸漸融合了場景、戲 服、道具等戲劇元素,因此照片呈現的是演員所扮演的角色,有 時也會是他們從未演過的角色。直到19世紀末,戲劇的舞台照 才開始出現。20世紀初期,演員會以個人或合照的形式,在舞台 上保持靜止姿勢以便讓攝影師來拍攝,像是表演戲劇之餘的一個環節,這一做法沿襲至今。法國表演藝術系教授尚托·美耶·普 托羅斯(Chantal Meyer-Plantureux)女士在她的著作中介紹說, 這種為攝影師預留時間拍劇照的做法,有時會導致兩位來自不 同機構的攝影師,拍出完全相同的照片。但這一做法對於攝影師 來說是很有必要的,否則無法拍出清晰銳利的照片,因為當時的 鏡頭拍攝光敏材料或動態效果還不夠理想,加上劇院裡光線太 暗,難度就更大。不過還要考慮的思想觀念的因素,不同時期和 社會環境下所要求的照片也是大不相同的。

ART.ZIP: Are there any specific categories of theatre photography? What are the main functions?

JA: I have mentioned early theatre photography, which is portraiture. There is also the ‘staged’ or photo-call photo, which immobilises, sets up, or even invents a scene from the play. This style allows a great deal of freedom for whoever is making the image (the director or the photographer), and the idea of giving a ‘faithful’ rendition of the play seems less important than creating a ‘dramatic’ image. As with the actor portraits, theatre photography often can be understood as a sub-genre of photo- graphic practices. There are thus examples of theatre photography that embrace the documentarist/reportage modality and indeed its aesthetic. In this mode, theatre photography is often taken ‘live’ (although rarely during an actual public performance), and the photographer behaves like a street photographer, capturing whatever happens, as it happens, seeking to find in the chaotic flow of the performance a ‘decisive moment’ (the term is of course from Cartier-Bresson). There is no dominant style of theatre photography at the moment, as far as I know.

As for the function of theatre photography, it really depends which theatre photography we’re talking about, and the role and function does change a great deal over time. Contemporary theatre photography is concerned either with prophesying a play (so marketing, publicity), or with remembering it (so theatre archives, or documentation, which is often created to support a request for funding from public or private sources; there is also a use within education and research for photo archives). Press photography obviously has a place, too, and theatre reviews are often accompanied by images (usually taken by one of a fairly small circle of professional theatre photographers).

It is worth mentioning performance photography, which is obviously closely linked to theatre photography, although one can identify some differences. There has always been a link between photography and performance art, be it in the 1950s, the 1970s, the 1990s, or in the last decade. And there has always been, alongside this affinity a suggestion of incompatibility: if performance is concerned with unrepeatable events, and with events that are seen by those present, there is clearly a possible contradiction with photography, as a technology of reproduction and mass distribution. Walter Benjamin never (to my knowledge at least) writes about theatre photography, but he seems to place theatre and photography in opposition: theatre is concerned with the hic et nunc, and photography is where cult value gives way to exhibition value.

Around the same time that Jacques Derrida was writing about Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, a number of perfor mance scholars became very interested in the question of whether, how, and why performance can be documented. At that point, one question was about how a piece of documentation (so, a photograph) might stand in for the perormance itself (this is the idea of fetish- ism), and this was a political question about performance’s place in or outside the sphere of the media. The document ing of performance also has legal implications, as seen in the case of four artists whose work had been photographed by Dona Ann McAdams in the USA in the early 1990s – the photographs became potential evidence in a hostile political environment.

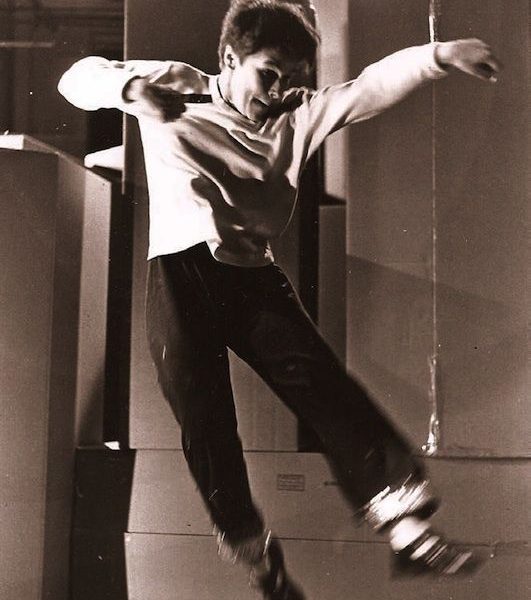

Much performance art photography corresponds to the aesthetic of reportage, and images are often black and white, blurry, grainy, or otherwise attesting to their being representations of something that took place. There is, however, another side to performance photography, which we might call photography as performance (the other work being photography of performance). This kind of photography creates photographic artworks, rather than documenting a live performance (although the distinction is actually far from simple). Examples of this might include the work of Cindy Sherman. The striking performance photography of Manuel Vason, who is particularly associated with artists operating in what is called ‘live art’ does not seek to document a live performance, but rather Manuel works with the performer to create an image, it is a collective process(‘collaboration’ is the word the photographer uses). The modality is actually comparable to that used in the 19th Century actor portraits I have described: photographer and sitter work together to create an image…

I think this opposition between capturing images and composing images is key to understanding theatre photography; it is an opposition that predates photography, but is still important today.

Another area that interests me is theatre photography with a precise function within the working process. This is quite rare, but there are, or have been in the past, a few companies that employ a photographer to photograph rehearsals and shows as part of the iterative processes of creation. I have previously written about the work of Sophie Moscoso (‘Theatrical photography, photographic theatre and the still’, in About Performance 2008), who was director Ariane Mnouchkine’s assistant at the Le Théâtre du Soleil, and whose photographs were used to check details, to keep a record of that company’s (long) rehearsal process, and to remind the director and sometimes the actor of previous choices of costume or of gesture). Bertolt Brecht made a great deal of use of photography in his work: he created detailed documents (called ‘modelbooks’) with text and photographs that would allow a show to be restaged with all of the nuance of physical configurations of actors and gesture required in his theatre style.

ART.ZIP:戲劇攝影都包括哪些類別呢?其各自的主要作用又是什麼?

JA:像我之前提到的,早期的戲劇攝影是以人物肖像的形式存 在。之後出現了舞台劇照,將劇中某個場景固定住進行拍攝,有 時甚至可以設計或重新製造出一個新的場景。這類戲劇攝影留 給攝影師或導演很大程度的藝術自由,目的是創作出效果誇張 的圖片,而不是對劇目如實地呈現。正如演員肖像一樣,戲劇攝 影也經常被看作是攝影學的分支,因而在戲劇攝影中,會融入記 錄片或報告文學的模式和審美標準。在這種情況下,戲劇攝影的 拍攝是在劇目上演的過程中完成的。當然,一般不會是對公眾演 出的時候。此時的攝影師就如同一位路人,捕捉舞台上的瞬間。 同時,要在雜亂無序的表演中尋找“決定性瞬間”,這一概念是攝 影家亨利·卡蒂爾·佈列松(Henri-Cartier Bresson)提出的。但目前 據我所知,戲劇攝影中還沒有一種處於主導地位的流派。

談到戲劇攝影的作用,我認為不同時期的戲劇攝影,其角色和作 用也有差異。當代攝影的主要功能是對戲劇劇目進行推廣或者 記錄,例如戲劇資料庫、文獻等,用來籌集公眾或私人資助,或 者作為教育與調研圖片資料。此外,還可以用作新聞圖片或劇評 配圖,不過此類攝影都是由一小部分專業戲劇攝影師來完成的。

值得一提的是表演攝影。它與戲劇攝影息息相關,但也有所不 同。無論是二十世紀50年代、70年代、90年代還是過去十年,攝 影與表演藝術總有著某種聯繫,同時兩者之間也存在不一致的 方面。對於表演來說,已經發生的場景無法重複,並且只有在場 的人才可以看得到。相比之下,顯然攝影具有截然相反的特徵。 攝影是利用技術進行內容再現和公眾傳播。據我所知,瓦爾特· 本雅明(Walter Benjamin)從未寫過關於戲劇攝影學的著作,但 他認為戲劇與攝影是相對立的:戲劇強調對此時此刻的展現,而 攝影則相反,突出的是展示價值。

同一時期,雅克·德里達(Jacques Derrida)創作了《檔案熱:弗洛伊 德學派印象》(Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression),眾多表演 學學者對記錄表演藝術的方式、目的以及必要性產生極大興趣。 當時人們關注的一個問題是,以一張圖片這樣的記錄形式,怎可 能代表整場表演呢?這種思想不但帶有拜物教的性質,而且從政 治的角度來看,是質疑表演這門藝術在媒體中和媒體之外的角 色。對表演的記錄也涉及到法律問題,比如美國攝影家當娜·安·麥 阿當斯(Dona Ann McAdams)在20世紀90年代初,拍攝了四位藝 術家的演出,但那些照片卻險些成為了惡劣政治環境的證據。

很多表演藝術攝影的審美標準與報告文學相符,此類圖片通常 具有黑白、失焦、粒狀等特徵,或者作為對過去事件的證實。與表 演攝影學相對的是攝影表演藝術。區別簡言之就在於,它是創造 以攝影為形式的藝術品,而非對表演進行記錄。例如美國攝影家 辛蒂·雪曼(Cindy Sherman)的作品就屬於這一類別。還有意大 利藝術家曼努埃爾·法申(Manuel Vason)創作的強烈震撼的表 演攝影作品,他專門與那些現場表演又不想被記錄下來的藝術 家合作,共同創作一幅圖像,這是一個合作的過程。這與我之前 提到19世紀的演員肖像作品在形式上確有可比之處,即攝影師 和模特共同合作來創作一張圖片。

我認為,這種捕捉圖像與創作圖像之間的對立關係,是理解戲劇 攝影的關鍵。這種對立關係在攝影學出現之前已經存在,至今仍 意義重大。

另外,戲劇攝影還具有某些特定的用途,我對此也很感興趣。一 直以來都有少數幾家公司會僱用攝影師拍攝彩排過程,用於展 示不斷創新的過程。此前我曾在《2008表演藝術文摘》上發表過 一篇關於蘇菲·莫克蘇(Sophie Moscoso)的文章:《淺談戲劇攝 影、攝影劇場與靜物》。 莫克蘇是法國舞台劇導演亞莉安·莫虛 金(Ariane Mnouchkine)在Th_.A_Ni_Nbtre du Soleil的助理, 她拍攝的作品就是用作檢查細節、記錄彩排過程、提醒導演和演員之前的道具或表演動作等。德國戲劇家貝爾托·布萊希特(Ber- tolt Brecht)在他的作品中融入了大量的攝影元素,他詳細記錄 了被稱之為“模版書”的材料,包括文字、圖片等內容。有了這些 檔案,他能夠重新改編一齣戲劇,同時將演員動作編排和手勢等 細微之處改成自己的舞台風格。

ART.ZIP: How do you define a good theatre photographic work? Any particular elements should be included, like costumes, stage design, characters and etc.? Any difficulties in doing theatre photography? Could you pick one or two works as examples? Or would you name any significant/influential theatre photographers?

JA: It’s not up to me! I think the interesting distinction might once again summon this idea of fidelity: surely a photograph might offer a good likeness, might look like a production, but such a photograph might not in itself be particularly interesting. Indeed, it is possible there might be a negative correlation between how representative a photograph is of a particular theatre work and its aesthetic value.

It is impossible to include everything in a photograph, in any case, and photographs of the whole stage are usually quite dull and flat; where- as the eye can move between elements while also seeing the whole, a photograph is fixed. The same problem applies in terms of light: the eye can adjust very quickly to lighting levels, and the eye and brain work together to deal with mixed lighting. Photographs can only be taken at one exposure and with one aperture setting (well, there are obviously composite forms of photography that combine multiple exposures.), so one element will always be privileged. This touches on some huge difficulties with doing theatre photography, technical and artistic. Even if recent technology is used, theatres remain difficult places to work, with poor lighting, issues of physical access, sightlines, etc. But theatre is – as Patrice Pavis has put it ‘photogenic’, so it’s some- times worthwhile. Theatres are also restricted spaces, and it is usually forbidden to take photographs in a theatre (indeed, it is increasingly forbidden to take photographs anywhere.).

There are many theatre photographers I could name, and there is a very varied collection of images taken over the last century-and-a-half. Nadar’s portraits of Charles Deburau as Pierrot remain astonishing – Walter Benjamin (to quote from him again) suggests that early photo- graphs, specifically daguerrotypes, had an ‘aura’ because of their long exposures – he describes them growing, and these portraits I think at- test to that. Etienne Bertrand Weill produced extraordinary images of theatre, and particularly of mime. I have recently been looking at the theatre work of Angus McBean. McBean’s pictorialist approach to photographing theatre is the opposite of the reportage style that replaced it, and it never gained the photographer much acclaim. It is however, an engaging attempt to create images that are as dramatic as the productions themselves, and I think is worthy of new attention. I have also been looking at examples from the large volume of mid- century theatre photography from eastern Europe, particularly Hungary and Czechoslovakia, which seems to draw on theatre as the basis for impressive formal experiments. I am currently researching Chinese theatre and performance photography, and am currently particularly interested in the work of Rong Rong. I have also been looking at the work of Martine Franck, who sadly died last year. Franck is probably best known for her street and travel photography (she was a member along with her husband, of the Magnum Photos). But she was also a photographer at the Le Théâtre du Soleil from its foundation until her death, and took images of the company’s productions. Some of these show the sumptuous sets and costumes of the Soleil in the style of classical paintings, others are intimate portraits of actors in rehearsal, or preparing to go onstage. In terms of performance photography, there is a great deal of extraordinary work by Dona Ann McAdams. In terms of Britain, the work of Hugo Glendinning ranges from stage photographs to much more experimental work with Forced Entertainment. Ivan Kyncl, who died in the mid-2000s, produced some compel- ling images from the British stage.

ART.ZIP:在你看來,什麼是好的戲劇攝影作品?應包含哪些特 定元素(如服裝、舞台設計、角色之類)?戲劇攝影的過程中會遇 到什麼困難?你能舉一兩個作品作為例子?或你能列舉出一些 重要的/有影響力的戲劇攝影師?

JA:什麼是好的戲劇攝影作品,我說了不算。但我認為,其獨特 之處或許再一次讓我想起“逼真度”這個概念:一張照片可以很 逼真,可以看似是一個作品,但是,照片本身可能不是特別有趣。 確實,一張照片對真實場景的體現程度和它本身的藝術價值有 可能是成反比的。

在任何情況下,一張照片都不可能包羅萬象,舞台的全景照通常 是單調乏味的。眼睛可以在看見全景的同時遊走於每個要素之 間,但照片卻是固定的。在光線方面,同樣的問題也存在。眼睛可 以快速適應光線強度,眼睛和大腦協同處理混合光影。但是,攝 影師只可以用一個曝光度和一個光圈設定來拍一張照片(當然, 目前存在一些多重曝光的合成方式),所以總會傾向於某個要 素。這牽扯到了戲劇攝影過程中一些巨大的難關,不論是在技術 上還是美學上。即便是用了最新的技術,舞台仍不是一個容易拍 照的地方,無論是昏暗的光線、攝影師准入許可、還是視線等原 因。但正如帕翠斯·帕維斯(Patrice Pavis)所說,舞台是“鏡頭的 寵兒”,所以有時還是值得一拍的。劇院是受限區域,所以通常情 況下不允許在劇院內拍攝。(確實,現在上哪拍照遇到的限制都 越來越大。)

有許多戲劇攝影師我可以列舉出來。過去一個半世紀,他們鏡頭 下的影像也是精彩紛呈。納達(Nadar)的肖像作品,“扮演皮埃 羅的查爾斯·德比羅(Charles Deburau as Pierrot)”,依然非常驚 艷。華爾特·本雅明(Walter Benjamin)說(再次引用他的話):早 期的照片,尤其是達蓋爾銀版照(daguerrotypes),都因為曝光 時間過長而存在光暈現象。他形容那是正在不斷的完善中,這 些肖像畫證明了這點。 埃蒂安·貝特朗·維爾(Etienne Bertrand Weill)拍下了非凡的舞台照片,特別是啞劇。我最近也觀賞了安 格斯·麥比恩(Angus McBean)的作品。麥比恩繪畫風格般的攝 影手法與後來取代它的那種報告文學的手法截然不同,這並沒 有給這位攝影師帶來太多的讚譽。但是,這是一種勇敢的嘗試: 試著去創造出與戲劇作品一樣有戲劇效果的畫面,我認為這值 得我們重新審視。我也觀賞了東歐大量的上世紀中葉的戲劇攝 影作品,特別是匈牙利和捷克斯洛伐克的作品,似乎認為舞台是 正式試驗的基礎。我目前在研究中國的戲劇攝影作品,我特別 對榮榮的作品感興趣。我也一直在觀賞瑪提恩·法蘭克(Martine Franck)的作品,他去年不幸過世了。法蘭克最出名的可能是她 街景和旅行的攝影作品(她和她丈夫都是瑪格南圖片社的成員)。但她同時也是太陽劇院(Le Théâtre du Soleil)的攝影師, 從該公司誕生起,直至她生命結束。她為該公司的許多作品拍過 照。有些照片用古典畫的手法體現了奢華的場景和服裝,其他則 是演員排練時或準備上台時的肖像畫。在活動攝影方面,當娜· 安·麥阿當斯(Dona Ann McAdams)有許多非同凡響的作品。而 在英國,雨果·格蘭迪寧(Hugo Glendinning)也有許多作品,從 舞台照片,到與Forced Entertainment合作的更具實驗性質的 照片。伊文·肯克爾(Ivan Kyncl,卒於2005年左右),也創作過許 多關於英國舞台的迷人照片。

ART.ZIP: What do you think of the differences or similarities be- tween theatre photography and other photography?

JA: Theatre photography is probably best understood as a minor, marginal form of photography. There are very few professional theatre photographers, and there are relatively few outlets for theatre photo- graphs to be disseminated. I change perspectives a lot as to whether theatre photography is actually all that different from other forms of photography. Certainly, there are specific questions, risks, and rewards, but I currently don’t make a clear distinction. The difference is on the viewer side – how a photograph is viewed shapes what it means.

I do think theatre photography remains interesting, however. And it has a bearing on wider questions about photography, and indeed be- yond. For example, theatre photography is relevant in examining a phenomenon like the photographs documenting torture and abuse at Abu Ghraib by US military police. As Victor Burgin has pointed out, these images made a mockery of the postmodernist resistance to ide- as of photographic truth. But these snapshots were also highly theatrical – tableaux vivant, staged for the camera.

ART.ZIP:你認為戲劇攝影和其他攝影有什麼異同?

JA:主流觀點可能認為戲劇攝影是一種相對小眾的,次要的攝 影形式。而專業戲劇攝影師的人數非常少,供戲劇攝影作品傳播 的渠道也不多。至於戲劇攝影是否真的與其他攝影完全不同,我 也經常改變看法。這行業的確存在一些疑問、風險和回報,但目 前,我認為它與其它攝影沒什麼明顯區別。區別在於觀眾怎麼去 看。一張照片的意義取決於觀眾怎麼去看。

但我認為戲劇攝影還是相當有趣的。它不僅與圍繞攝影更廣泛的 討論息息相關,甚至超越這個範疇。比如,戲劇攝影在審視照片記 錄“美軍虐囚”這一現象發揮著一定作用。正如維克多·博格恩(Vic- tor Burgin)指出那樣,這些照片嘲笑了後現代主義者對照片真相 的抵觸。但這些快照也非常具有舞台效果:十分逼真和入鏡。

ART.ZIP: What books would you recommend if we want to know more about theatre photography?

JA: There are very few books about theatre photography. Books on theatre, although they draw on theatre photographs (although, at least in Britain, they do this quite minimally – the CNRS ─ Centre national de la recherché scientifique in France does a more sustained promotion of theatre photography), rarely engage with the subject, and there is little or no mention of theatre photography in most works on photography. Again, theatre photography is quite a minority and marginal affair.

Chantal Meyer-Plantureux’s 1992 book La Photographie de Théâtre ou la memoire de l’ephemere (in French) remains the most substantial. There are a number of articles on everything from the actor portrait to performance documentation. Rebecca Schneider’s latest book contains a section on the relationship be- tween theatre and photography. There are some good books of theatre photographs: I would recommend works by Martine Franck, Nicolas Treatt. Some works have considered the theatricality of photography, for example Max Kozloff’s The Theatre of the Face. I would also (with some reservations!) recommend my own book, Theatre & Photography, which will be published next year.

ART.ZIP:如果我們想了解關於戲劇攝影的更多信息,你會推薦 什麼書?

JA:關於戲劇攝影的書非常少。關於舞台戲劇的書,雖然也有 提到戲劇攝影,但鮮有深入探討這個話題(至少在英國這方面 的工作非常有限,但法國的國家科學研究中心(CNRS─Centre national de la recherché scientifique)卻為推動戲劇攝影而作 出了更為持久的努力),而在大多數攝影書籍裡面,提到戲劇攝 影的也非常少,甚至沒有。所以,我說戲劇攝影是小眾的、次要的 攝影形式。

尚托·美耶·普托羅斯那部1992 年的著作《戲劇攝影與短暫 的記憶(La Photographie de Théâtre ou la memoire de l ’ e p h e m e r e ) 》( 法 語 版 本 ) 仍 是最有分量的一本書。裡面有 多篇文章詳細地闡述了戲劇攝 影,從演員特寫到演出經過。 瑞貝卡·舒內德(Rebecca Sch- neider)最新的書也有專門闡 述舞台和攝影關係的一小段篇 章。另外還有一些不錯的書籍, 我會推薦馬迪恩·法蘭克(Mar- tine Franck)和尼古拉斯·特瑞 特(Nicolas Treatt)的書。有些 書已思考過了攝影的戲劇化效 果,比如馬可西·科茲洛夫(Max K o z l o f f )的 書《 戲 劇 之 臉( T h e Theatre of the Face)》。我同時 也推薦我自己的書《舞台與攝影 (Theatre & Photography)》, 這本書將在明年出版。