TEXT BY 撰文 x BECKY SHAW 貝奇·肖

TRANSLATED BY 翻譯 x SUDONG CAI 蔡蘇東

Every self-respecting young artist at some point or other takes the wheel and organises a project or group show that involves others. Curation is now a multi-functional word expressing the role of the person who looks after a collection of artworks, the person who decides which objects sit next to each other in an exhibition, the person who works closely with the artist to develop a new project, to the person who displays their colleagues’ or friends’ work in an empty warehouse. The Taxi Gallery is led by an artist, Kirsten Lavers, and it is interesting to ask whether an artist working as curator represents any significant development from established curatorial practices. By exploring the role of the curator, then focusing on the relationship between artist and curator, the following text will ask whether artist-curator models maintain conventional artist-curator relationships (whatever these are) or offer something different. To explore the subtleties, a small number of different curators/artists were asked to describe their aspects of their practice.

We often talk of curators (and writers, critics etc) as gatekeepers to visibility in the artworld. Opportunities to work with reputable organisations normally happen through a process of endorsement, when artists are validated by working with other recognised establishments. As the person who has some control over what represents art of the highest quality, the curator is an arbiter of taste, appearing to have the authority to represent a society’s values. As a result of this, artists, and theorists etc, are often critical of, and frustrated by, this power relationship. However, the curator’s role and control over artistic visibility is complex. The (good) curator is the intersection between artist and audience, a go-between looking to ensure the audience is given the best possible opportunity to engage with an artist’s work, and that the artist has the best possible chance of communicating to an audience. Artists seek to occupy this territory by running galleries etc, but there is also a gradual movement towards artists taking control and delighting in this relationship with an audience, through practices deemed ‘relational’ or ‘engaged’. So where does this leave the role of the curator? Not redundant of course, as when institutions become involved with these kind of practices they still need someone to mediate the relationship between the artist and the institution and to make sure the project is a success. However, the advent of these practices, plus 1970s onwards practices of institutional critique, and a general critique of cultural authority have all led to a decline in confidence or belief in the power of curators.

One contemporary debate about museum collections, reveals this uncertainty. Many museums have been getting rid of their collections, concerned that the objects will reveal their own vision and connoisseurship. They doubt their authority, concerned that their vision of the past/present might be wrong and that it ought not shape the future so heavily. Rather than being the gatekeepers of culture they have become nervous of imposing any views whatsoever. This ‘hands off’ approach has worrying implications for the future, leading to empty or safe museum collections(1). Perhaps the current artist-led projects or other curatorial practices which seek to ‘give space’ to artists also fall into the same trap, forgetting that the battle between two conflicting visions might actually generate something exciting.

Artists operating as curator generally adopt the same practices as used by their salaried colleagues, but their reasons for taking this action may be different. Artists function as curators in an attempt to gain visibility for practices they respect, including their own. It is an attempt to own the process of distribution rather than be subject to it. Martha Rosler indicates the conventional differences in the roles of artist and curator or distributor:

‘Artists may channel mysterious energies, but others get to make the choices. Choice trumps creation, and choice is linked to all rewards, including an enlarged audience for the chosen artists’ work’(2)

Artists who set up galleries also do it because they believe they may be able to do it better than curators. This belief may be because they feel they understand the needs of artists better (although many curators have also been artists) or because they think they are free from institutional conventions or pressures. Some believe they can do it in a way which does not involve the repetition of what is perceived to be conventional hierarchies. If novel structures are found this is exciting, but many repeat the same structures but claim to be different simply on the grounds of being artist-led, as Liam Gillick suggests,

‘the idea that a show organised by an artist is essentially more worthy than a show put together by a gallery works against a pointed and radical reassessment of how art could now be in the sense that it reinforces the idea that artists are fundamentally interesting and operating under a different (read higher) moral code than anyone else, especially art dealers’(3)

While the product of an artist curating may not look different, there can be different social outcomes. One reason for artists setting up galleries or curatorial projects is the desire to energise their locality by providing a focus for artistic activity and dialogue. Artist Ricardo Basbaum believes that ‘etc-artists’(4) , or artists that curate, write etc, do create something qualitatively different, activating a series of networks, which enable the circulation of practice through non-institutionalised structures. It is the actual affect on relationships which is different, above and beyond what is achieved in the art work itself,

‘When artists curate, they cannot avoid mixing their artistic investigations with the proposed curatorial project: for me, this is the strength and singularity they bring to curating. The event can have a chance to become clearly embedded in a network of proximate knots, enhancing the circulation of “sensorial” and ”affective” energy – a flow which the field of art has managed to comprehend in terms of its economy and circulation.’(5)

Liam Gillick also testifies to artist-led activity as a force for generating communication between artists, to a greater extent than in institutional practices:

‘not to say that artists are resistant to being represented by that system, more that they have developed their own proven means by which a dynamic discourse can take place’(6)

Most importantly, some artists curate because, like some curators, they are deeply interested in and committed to the practices of others, or the discursive process involved in forming a new work, for example, Robin Klassnik and Matt’s Gallery.

The only time artist as curator (or indeed curator as curator) changes the conventional structure of ‘worker’ and ‘owner of the means of production’ is when they find a different structure of operation and the definitions become irrelevant:

‘a curator has become just another individual in the complex web of cultural production that defines how we contextualise current activities and therefore the whole process is open to flux and change’(7)

As Nicolas Bourriaud describes in ‘Postproduction’, there are a range of practitioners who are working as ‘producers’. This word describes most effectively a process which involves creating a ‘production’ from beginning to end. The distribution is incorporated, like any commodity, in its conception. Bourriaud discusses this as the territory of artists, seldom mentioning curators, and yet these practices are the terrain of both, and perhaps the arena where both can work together without distinction. However, many of the projects Bourriaud describes still take place in large institutions. The curator is never mentioned but I suspect they are still involved. Some might argue that such a fluid world of ‘producers’ would lead to a loss of unique skills and important distinctions. However, perhaps in reality the skills are not unique, but simply a socially created distinction serving the needs of institutions.

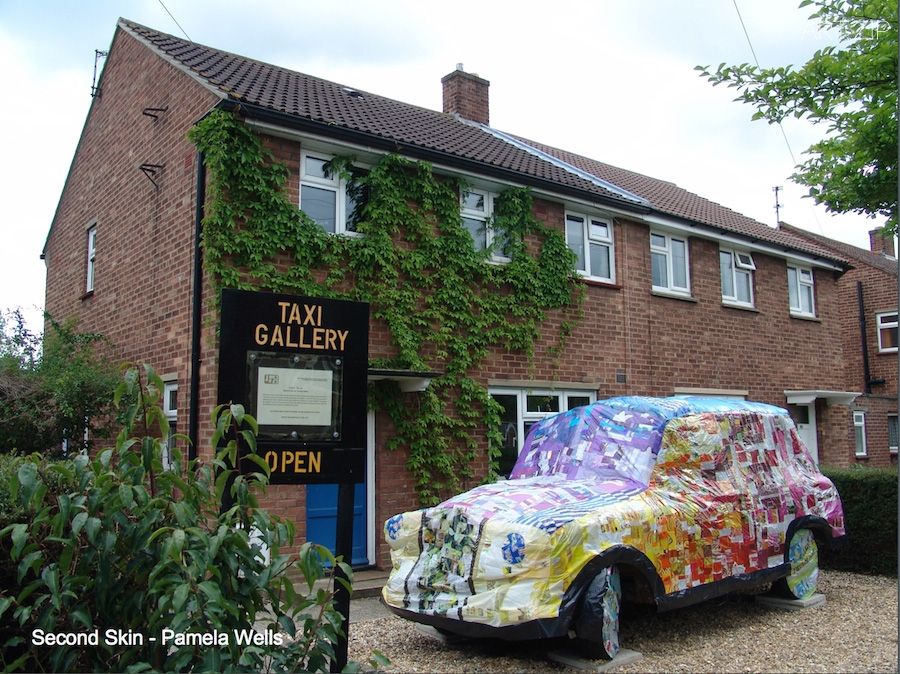

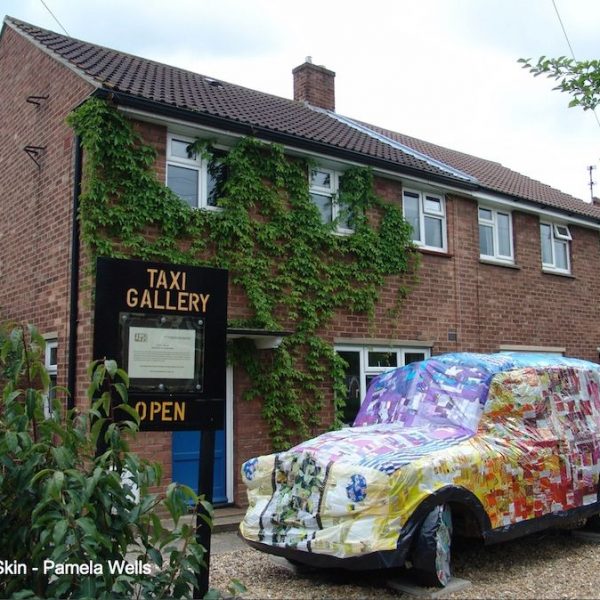

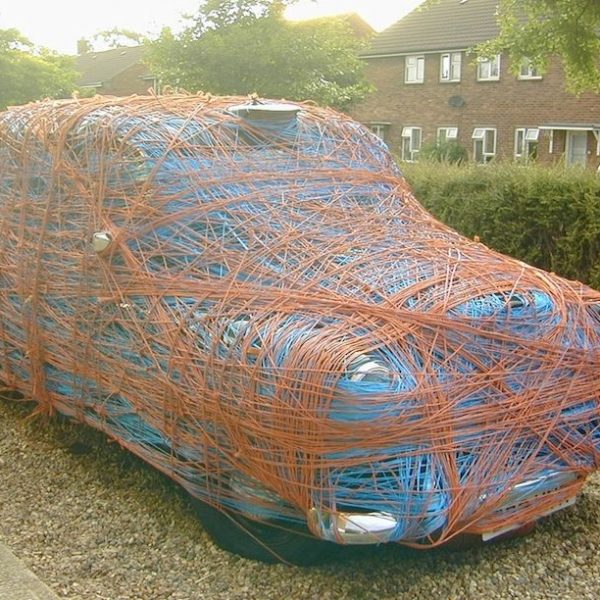

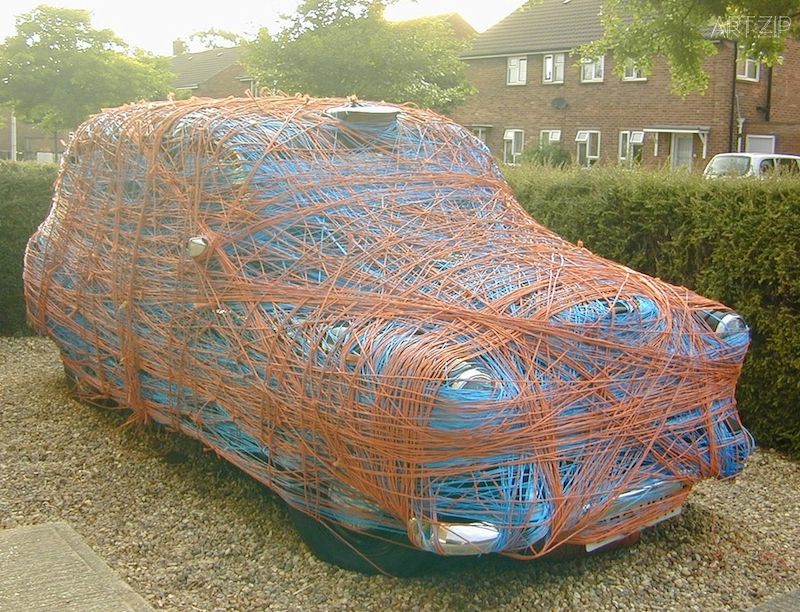

- Transmutation by David Kefford

- Second Skin by Pamela Wells

Throughout the range of practices encompassed in curating there is always a relationship between an artist and a curator, and this relationship is rarely discussed and is not intended to be visible in the resulting work. In a formal gallery context the relationship is contracted, to clarify conditions of pay and tasks, whereas in the situation of an artist curating a show with artist friends there is no desire for contracts. However, neither the paper, or social, contract accounts fully for the unique environment, atmosphere and expectations created by an individual curator, and then the form of the relationship that is developed with the artist. It seems that this relationship, which normally has a power structure purely because one person is in charge of the distribution of the work (or the purse strings) is never black or white, and has enormous potential to be explored.

In order to understand whether Kirsten Laver’s role as artist-curator of Taxi Gallery is different to role of a curator, three questions were put to Kirsten and also to Ceri Hand, Senior Curator at FACT, Liverpool. The same questions were also put to Kelly Large, an artist who uses curatorial processes to form her work, for example in the project QSL, where artists and writers are commissioned to interpret an audio playlist (built by Large herself) resulting in a radio broadcast work.

‘Is the relationship between you and the artists you work with ‘equal’?’

Kirsten sees the process of working with an artist as an ‘exchange’, a moment when either artist and curator initiate a working relationship, leading to joint working,

‘Each relationship is a conversation, a series of stages/steps in which at different times, either the artist or myself as project initiator takes the lead to propose, suggest, draft, time-table, imagine, experiment and make …. remaining open to response or suggestions from the other – working towards a sense of shared agreement on how to proceed.’

Kirsten does seem to consider equality as desirable, but it is interesting that equality is not something that is in place from the outset, but is something that is strived for and built, strangely parallel to the construction of the work.

‘Each project is very different – but generally, equality – based on agreement upon, and respect for, demarcated areas of control – is what ‘we’ (artist and curator) attempt to arrive at as the project develops towards exhibition.’

When asked about equality Kirsten seems to see it as something worth pursuing, although based on separate areas of expertise. Ceri Hand sees the term as a misnomer,

‘Equality somehow infers that there would be a level that you would reach, a sameness…I don’t think this is necessary or even desirable – I don’t want to be an artist & I presume the artist is happy doing what they are doing, however there are levels of shared experience & understanding from both parties, presumably with a similar desire in mind – that of finding the best way of communicating the artists work to a wider audience (however big or small that may be)…. For me the role of the artist is totally dependent on who that artist is and how they like to work..’

The relationship between artist and curator (or organisation) at a large organisation will be subject to contract, and therefore perhaps it might be expected to be more rigid. However, Ceri Hand, also describes a fluid relationship,

‘In my experience a good working relationship with an artist means that you both respect each others strengths & ideas, recognising that together you can make something new & hopefully exciting, that perhaps either one of you wouldn’t come to by yourselves or with anybody else…the ‘power’ balance shifts all the time throughout the creative process…if you have set off on the right foot then this is an interesting process…

In contrast, when asked if the relationship between artists and herself is ‘equal’, Kelly Large says,

‘No? Usually I ask participants to operate within or contribute to a framework I have set up. Although I create the situation, the manner in which the participant engages help shape the project development and outcomes. So I would say that the ability to affect the circumstances that have been set up shifts between me and the contributors at different stages in a project’

All three- the ‘curator’, the ‘artist-curator’ and the ‘artist who uses curation’- have a different opinion of equality. However all describe a relationship that is never concrete but always shifts, each person in the equation responding to the other. However, in all three relationships the curator remains the broker of visibility. In the Taxi Gallery, decisions regarding timing, situation in the gallery programme, archiving and documenting and ‘the paratext of the exhibition (its framing through publicity, associated event opening, talk, performance etc)’, are Kirsten’s responsibility, although the artist is given space to suggest alternatives etc. The installation is the task left to the artist with Kirsten’s support where necessary. Similarly, Kelly Large indicates,

‘ultimately I decide how the participants contributions are ‘played out’ in the world – I use the contributions to mediate an idea (rather than find an idea/theme to mediate a group of works) so the project as a whole is privileged over the individual works. So the final ‘orchestration’ is my ‘voice’ and this personal contextualisation of the works means I have the ‘final say’..’

The Successful Relationship

When asked what qualities lead to successful or unsuccessful curatorial relationships Kirsten points out that prior knowledge and trust are significant factors. However, Kirsten also indicates that working with friends makes the dynamic ‘harder to negotiate and unravel equitably’. It seems too much intimacy can lead to a struggle for power rather than more equalness. Kirsten notes that one experiment in working with an artist who she shared no common values with was difficult, but not necessarily unsuccessful artistically. Ceri Hand also indicates that difficult relationships can be fruitful,

‘Sometimes it’s exciting & challenging to work with people that you have very different ideas/morals/belief systems/politics/sense of timing/sense of humour etc. from & it can add something to your practice, develop you in some way & sometimes you should just trust your gut & steer clear!’

Trust, honesty and being prepared to pursue the dialogue are important to Ceri,

‘…or at least establish a set of guidelines (that can often be kind of unspoken) with which to embark on that relationship…’

Unwritten or unspoken guidelines can often be a recipe for disaster, but it seems that in these contexts, it works if both parties are prepared to ‘go the distance’ in negotiation.

Definition of Roles

When asked how roles and responsibilities are defined, Kirsten indicates that they are deliberately left undefined,

‘Roles of artist and curator are deliberately not clearly defined beyond the brief sketching out of what I can offer as project initiator in the “info for artists” section of the website……. Whilst retaining core features my role shifts in response to the particular needs and personality of the artist involved in each exhibiting project.’

Likewise, Ceri Hand says that ‘all relationships are about defining them when you are embarking on them or in them to an extent’. Kelly Large indicates that some of her curatorial relationships, such as the use of an existing material are very clear but then both her and Kirsten note how sometimes the very basis of roles can shift:

‘certain approaches to curatorial activity and artistic production are very similar –both practices can involve research, posing questions, reusing existing forms etc. Many of the people I work with operate as both artists and curators on a daily basis anyway. When these kinds of dialogue are created the roles of curator and artist can be very hard to distinguish and the separating of the roles becomes defunct. I am interested in this shifting of position and the issues of status, ownership, authorship, transmission and reception it produces which is probably why I work in the way I do.’--Kelly Large

‘I blur these roles within all aspects of my practice so within the context of the gallery the exact nature/remit of our roles is negotiated and arrived at, for each relationship, through the conversation and exchange process described above.’ --Kirsten Lavers

Ceri Hand does not describe the same shifting boundaries between roles of artist and curator, however, beyond this the description of the fluid process of negotiation is remarkably similar.

Who’s Driving?

It seems that whatever the kind of practice- ‘curator’, ‘artist-curator’ or ‘artist using curatorial activities’- the relationship is never concrete but is constantly re-interpreted and shifting. It seems though, that in all examples, the curator, by definition, holds the strings of distribution so this power basis is rarely dismantled.

‘issues of connoisseurship and validation are still problematic when a organisation/individual selects artists to work with, regardless of whether they are an artist-curator/artist-led-organisation. The relationship between those who control the mediation/ distribution/ visibility mechanisms and those who don’t naturally creates positions of more power or less power’--Kelly Large

However, perhaps this power relationship isn’t a bad thing. ‘Equality’ probably is, as Ceri Hand indicated, irrelevant, or impossible bearing in mind the significance of distribution and visibility structures. All three examples here indicate that harmony is also not vital and in fact a certain amount of control and knowledge is important, otherwise ‘no one is driving’’ and the project may lack direction or structure. A difficult relationship doesn’t necessarily lead to a bad project, but a preparedness to dialogue is seen to maximise the opportunity to communicate, for both artist and curator. Perhaps, indeed, seeing the relationship as a colliding of views (although not ‘colliding of drivers’!), rather than any dissolution can lead to exciting results. None of these ‘curators’ thought they were simply working to give space or opportunity for artists- all described a far more robust and active relationship where their own input mattered to the outcome. Perhaps having people who are prepared to justify their own beliefs and use their power to communicate work they believe to be significant is also important.

It seems that the processes and artist relationships of an ‘artist working as curator’ (like Kirsten) do not represent any significant departure from the activities of a salaried curator like Ceri Hand. Kelly Large’s activities differ more, being less about a negotiation. Issues of ‘gatekeeping’ or ‘quality arbitration’ remain in place for all three ‘curators’ although to different degrees. Where activities differ is perhaps their impact on artist’s and community networks, as Basbaum indicated at the outset. However, perhaps measuring Kirsten’s or indeed Ceri’s or Kelly’s activities in relation to a norm is irrelevant anyway, when what is of interest is the dynamic relationship that can develop, leading to a new work shaped by the curator as well as the artist. Perhaps we are moving closer, finally, to the recognition that art is never produced by one person(8). In a discussion at Static, Liverpool, Pete Clark(9) pointed out that ‘the tail wags the dog too much’- i.e. that we give curators, writers etc too much authority and responsibility for creating the artist’s work in the social realm. It was commented that artists can do without curators and writers etc, but not vice versa. Of course power structures are problematic but it is ridiculous to even speak of art today without recognising that visibility structures produce the work we examine . Art as we know it is produced by a complex web of actors and the further we go towards recognising and utilising this the better.

For the Taxi Gallery, the quality of the relationship with artists seems to occupy as much, if not more significance than the work itself. This might be because there is a greater emphasis on the cab’s relationship with the community, or because the relationship is only ever between two people- as there is no institution to mediate the relationship, as at FACT. However, further than that, it seems that the very relationship and its nuances are a process of construction akin to the artwork. It would be interesting to view each Taxi Gallery show as an articulation of a different relationship, the cab literally providing a structure that the artist can choose to inhabit, dominate or do battle with. It seems that, within the context of Bourriaud’s ‘production’-based practices there is a real opportunity for the curator-artist relationship and its’ power relationship to become recognised and critically articulated as part of the work’s context.

每位年輕藝術家到了某個時候,總會躍躍欲試組織一個藝術項目或一次群展。“策展”如今一詞多義,既可指照看藝術品、確定展品擺放的行為,又可指和藝術家親密合作開發新項目,或是在空曠倉庫展廳里展出同事或者朋友的作品。計程車畫廊(The Taxi Gallery)是由藝術家科爾斯頓·萊弗斯(Kirsten Lavers)創立的。藝術家同時充當策展人的角色,是否是既定策展慣例的一種進步?這個問題很有趣。下文將通過討論策展人的角色範圍,聚焦藝術家和策展人之間的關係,探討“藝術家策展人”模式是否維持了傳統的“藝術家策展人”關係(不管是什麼樣的關係),還是帶來新風貌。為了探索其中的微妙之處,我們訪問了不同的策展人/藝術家,讓他們來說說各自工作的方方面面。

我們經常說策展人(寫手、批評家等等)是決定誰能進入藝術世界之門的守門人。藝術家通常由於被賞識因而獲得和知名組織合作的機會,而通過和這些業已成名的機構合作,藝術家們的價值也得以證明。作為擁有何為最佳藝術最終判定權的人,策展人是品味的仲裁者,其似乎擁有代表社會價值觀的權威。因此,藝術家和理論家等等,通常對這種權力關係抱著批判的態度,同時也不免沮喪。然而,策展人對於藝術家能否進入藝術視野的影響和控制確實複雜。好的策展人是藝術家和受眾之間的交叉中樞,他是一位中間人,保證受眾能夠盡可能地獲得品味藝術家作品的機會,同時也保證藝術家能夠盡可能地與受眾交流。現在藝術家們嘗試著佔領這個重要的領地,他們運營自己的畫廊,等等,但是同時,現今也有一股藝術家當家做主,直接和受眾愉快交流的潮流,他們所憑借的,便是所謂的“關係式的”或“參與式的”做法。如此,策展人還有何用呢?當然,還是大有用武之地的,當有機構參與其中時,還是需要有人起到調和藝術家和機構之間關係的作用,保證項目成功舉辦。但是,這些做法,加上二十世紀七十年代以來學院批判的作風,同時還有對於文化權威的總體批判,都使得人們對於策展人權力的信心和信念有所下降。

而如今,一場關於博物館藏品的爭論也揭示了這種不確定性。許多博物館正在清理館藏品,擔心這些藏品所代表的是博物館的眼光和收藏品味。博物館質疑以往的權威,擔心他們對過去/將來的見解是錯誤的,同時認為他們不應該對未來橫加如此大的影響。因而,策展人不再是文化的守門人,他們無論給策展品施加什麼見解都如履薄冰。這種“不干涉”的做法對於未來而言是令人擔憂的,到頭來很可能導致博物館要麼空空如也,要麼其藏品都是保險平庸之流(1)。也許當今許多旨在“給予藝術家更多空間”的藝術家領銜項目或者其他策展做法到頭來也會落入此窠臼,忘記了正是衝突的見解之間的角力才可能產生令人興奮的東西。

身兼策展人的藝術家採取的做法往往和領著工資的專職策展人並無二致,但他們的初衷卻是不同的。藝術家策展人試圖要做的是讓他們所尊重認同的藝術實踐(也包括他們自己的)得到曝光的機會。這是一種掌控藝術傳播流程的嘗試,而不是反受其制約。馬薩·羅斯勒(Martha Rosler)道出了傳統藝術家和策展人或藝術分銷人之間的不同:

“藝術家能夠聚集神秘的能量創作,但其他人只能做選擇。選擇勝於創造,選擇帶來許多益處,包括給選定的藝術家作品帶來更多的受眾”(2)

自己開畫廊的藝術家這麼做是因為他們相信自己能比策展人干得更好。這或許是因為他們覺得自己能更好地理解藝術家的需求(儘管許多策展人本身也曾是藝術家),或者他們認為自己不受體制化的規範或壓力所限。有些藝術家認為他們能夠突破那些一再重複出現的傳統等級觀的束縛。如果可以找到新的結構,那是令人興奮的,但問題是,許多人重複著老一套,卻單單因為這是“藝術家領銜的”便宣稱自己是與眾不同的。正如利亞姆·吉利克(Liam Gillick)指出

“由藝術家組織的活動比由畫廊組織的活動更有價值,這種看法與當前對藝術領域進行的尖銳激進的重新審視背道而馳,因為這種觀點固化了一種思維,即藝術家們本質上都是有趣的,他們比其他人(尤其是藝術商人)有著不同(更高的)道德水平”(3)

也許由藝術家策展的出品看上去並無不同,但是卻有著不同的社會後果。藝術家之所以設立畫廊或者策展項目原因之一,是因為他們希望通過提供一個藝術活動和對話的聚焦點,使得他們所處的地區更加富有藝術活力。藝術家里卡多·巴斯鮑姆(Ricardo Basbaum)認為“類藝術家”(4)或者從事策展、寫作等等的藝術家確實創造出一些不同的東西,激活了一系列的網絡,使得這種做法得以在非體制化的圈子里流傳。正是這種對於關係的的感情差異使得藝術實踐已經遠遠超出藝術作品本身所帶來的影響。

“藝術家策展時,他們沒有辦法避免在策展項目中摻雜進自己的藝術追求:對我而言,這就是藝術家策展的優勢和獨特性。一個項目很有可能成為關係網裡另一個項目的紐結,促進‘感覺’和’感情‘能量的傳播,

——這股能量可被理解為藝術界裡的的流動力量,不管是經濟上的還是流通意義上的。”(5)

利亞姆·吉利克也指出,藝術家主導的活動可以促進藝術家之間的交流,而且比體制化的做法更有效:

“不要說藝術家很反對自己被某個體系所代表,那是老調子了,現在他們已經有了自己的一套方法論,使得對話能夠持續不斷地發生”(6)

最重要的是,有些藝術家之所以從事策展是因為,像其他策展人一樣,他們對於他人的藝術實踐或者創作新作品的思維發散過程非常感興趣,就如羅賓·克拉斯尼克(Robin Klassnik)和他的馬特畫廊(Matt’s Gallery)一樣。

使得作為策展人的藝術家(或者實際上就是作為策展人的策展人)改變“工作者”和“創作方式的擁有人”傳統結構的唯一情況是,他們發現了不同的運作方式,同時舊的定義不再符合時代:

“策展人變成了文化生產複雜大網上的普通一員,這張大網定義了我們應該如何把當下的活動放到語境之中,因此整個過程都是流動變化的”(7)

尼古拉斯·伯瑞奧德(Nicolas Bourriaud)在《後期製作》中描述到,有一些從業者的身份是“製作人”。這個詞最有效地描述了涉及創作由始至終的方方面面,像所有的商品一樣,創作從一開始就包含了傳播的概念。伯瑞奧德的討論涉及藝術家的領地問題,但卻極少提及策展人——但這些實踐實際上是二者的交集,或是二者可以無分界域地進行共同合作。然而,許多伯瑞奧德描述的項目依舊只能在大型機構中才能發生。策展人從未被提及,但是我認為他們還是參與其中的。有的人可能會爭論道,這樣一個由“製作人”主導的易變的世界會使得藝術中技術獨特性和差異性流失。然而,可能在現實中技術不是獨特的,但是一個簡單的社會差異性便足以符合機構的需要。

貫穿策展活動始終的總是著藝術家和策展人的關係,這種關係甚少被討論,在作品中不(也不應該)可見。在正式的畫廊語境中,這種關係是通過合同固定下來的,其中講清了支付條件和任務,但在藝術家策展朋友作品的情況中,卻甚少有簽署合同的意向。然而,不管是紙面或者非正式合同都無法對個人策展人所制定的獨特環境,氛圍和期許,以及和藝術家形成的關係負責。這樣的關係里通常都有著權力結構,因為總有一個人負責著一個作品的流通(或藝術家的錢包),所以這樣的關係從來都不是黑白分明的,而是有著可以探索的空間。

為了理解科爾斯頓·萊弗斯在計程車畫廊中的藝術家策展人是否異於策展人的角色,我們給科爾斯頓和利物浦藝術與創意科技藝術基金會(FACT-Foundation for Art and Creative Technology)的資深策展人凱里·漢德(Ceri Hand)提了三個問題。我們也向凱利·拉奇(Kelly Large)提問了同樣的問題,她是一位利用策展過程來形成自己作品的藝術家,比如在QSL項目中,藝術家和作家被委託解讀一份音頻播放列表(由凱利·拉奇自己完成),從而完成一個無線電廣播作品。

“你和與你合作的藝術家關係‘平等’嗎?”

科爾斯頓把和藝術家合作的過程看作是一種“交流”,當藝術家和策展人開始了合作的關係,接下來便是通力協作,

“每一段關係都是一個對話,一系列的階段或步驟,在其中,藝術家或作為項目發起人的我會率先提議,建議,起草,設定時間表,想象,試驗以及採納他人的反饋或者建議——力求獲得如何進行項目的統一意見”

科爾斯頓似乎認為平等是理想的狀態,但有趣的是,平等不是一開始就存在的,而是必須爭取和建立的,其和作品的創作之間是奇妙的並行不悖的關係。

“每個項目都是非常不同的——但總的來說,基於共識和尊重各自的職權範圍之上,‘我們’(藝術家和策展人)力圖做到從計劃到展出都能實現平等。”

當問及平等問題時,科爾斯頓似乎把其看成是一種值得追求的東西,儘管其基於不同的專業範圍有著不同的意義。凱里·漢德卻認為“平等”是個誤稱。

“平等似乎暗示著你需要達到某種程度的相同性……我不認為這是必要的,甚至是理想的——我不想成為藝術家,我認為藝術家樂於從事自己的創作,藝術家與策展人之間是有著某種程度的共同經驗和共識,比如說有著類似的理想——找到最佳方式來把藝術家作品傳達給更多受眾(不管本來有多少)……對我來說,藝術家的角色完全取決於這個藝術家是誰以及他們工作的方式。”

大型組織里藝術家和策展人(或組織)之間的關係取決於合同,因此這種關係可能會更加嚴格。但是,凱里·漢德也描述了一種靈活的關係,

“依我的經驗,和藝術家之間有著好的工作關係意味著你們互相尊重各自的長處和想法,意識到合作可以帶來新的,甚至是令人興奮的東西,而這些東西是你自己一個人或者和其他人合作無法實現的……‘權力’的平衡在創新過程中一直變化不定……如果你一開始就走對了方向,那麼這就將是一段有趣的過程……”

相比之下,當問及凱利·拉奇與藝術家的關係是否“平等”時,她說,

“可能不是吧?我一般會讓參與者在我設定的框架里操作,或者幫助我構建框架。儘管是我做的場景設定,但是參與人的協助也起到了推動項目發展以及影響最終結果的作用。因此我會說,在已經設定的場景中我和參與者之間對項目的不同階段所帶來的影響是一直變動的”

“策展人”、“藝術家策展人”和“使用策展方式創作的藝術家”這三位對平等都有著不同的看法。但是在他們的描述中,總是有一種不確定,時刻變化的關係,仿佛方程式中的每個人都會依據他人的變化而變化。但是,在所有這三種關係中,策展人都是藝術可見性的安排者。在計程車畫廊中,關於時間安排、畫廊項目情況、存檔記錄和展出“準文本(推廣計劃,和展出有關的開幕式、講話、表演等等)”的決策都是由科爾斯頓負責的,儘管藝術家也有建議的權力。至於布展安裝則是藝術家的工作,如有必要,科爾斯頓也會提供幫助。類似的,凱利·拉奇也指出,

“最終我決定參與者的貢獻是如何展現出來的——我把他們的貢獻用來調和一種觀念(而不是找一個觀念/主題來調和一系列作品),因而項目總體上是凌駕於個人作品之上的。因而最終的這段‘管弦樂曲’發出的是我的‘聲音’,這種個人對於作品的語境化意味著我有著‘最終決定權’……”

成功的關係

當問及什麼樣的特點會帶來成功或者不成功的策展關係時,科爾斯頓指出先在的知識積澱和信任是關鍵因素。但科爾斯頓也提出,和朋友合作使得這種關係動態“更加難以平等地協商和直言利害”。似乎關係越親近,越會導致權力的爭奪而不是帶來平等。科爾斯頓提到了有一次她和一位與她並無相同價值觀的藝術家合作的艱難經歷,雖然這樣的合作未必會帶來藝術上的失敗。凱里·漢德認為艱難的關係也可以結出豐碩的成果,

“有時候與和你有著不同想法、道德觀、信仰系統、政治見解、時間觀念、幽默感等等的人合作是令人興奮和極具挑戰的。這能給你帶來新的東西,讓你自己有所進步,有時就該相信自己,大膽往前沖!”

對於凱里來說,信任、誠實以及做好對話的準備是很重要的因素。

“……至少設立一套關於行為關係的原則(也可以不言明)……”

非書面或者不言明的原則很可能招致災難,但是在這樣的情況下,如果雙方都準備在協商中“跑完全程”,那麼這些原則就是有作用的。

角色定義

當問及角色和職責是如何定義的,科爾斯頓說,這兩者故意不進行定義,

“網站上的‘藝術家須知信息’已經包括了我作為項目發起人能夠提供的東西的簡述,除此之外,我們故意不明確界定藝術家和策展人的角色……保證核心任務的同時,在每個展覽項目中依據特定的需求和不同的藝術家個性,我的角色是會變化的。”

與此類似,凱里·漢德認為“當你開始工作或者某種程度上投身其中時,所有的關係實際上都是在界定角色”。凱利·拉奇說,一些她的策展關係是很清晰的,比如使用現有材料的情況等等,但是她和科爾斯頓都指出,有時,角色變換是不可避免的:

“策展活動和藝術創作的某些方法是很相似的——兩者都包含研究、提出問題、使用現有的形式等等。和我合作過的許多人每天都身兼藝術家和策展人兩職。當這樣的對話形成了,策展人和藝術家的身份是很難辨別的,想要把兩種身份區分開來也是行不通的。這種身份的變化,以及由此帶來的地位、所有權、作者身份、傳播和接受問題讓我覺得非常有趣,這也許就是驅使我如此工作的緣由吧。”--凱利·拉奇

“在我工作的各個方面我對這些角色的定義是模糊的,因此在畫廊的語境里,在任何一段關係中,我們角色的本質和職權都是可以協商和決定的,而我們採用的對話和交流方式已在前文有所提及。”--科爾斯頓·萊弗斯

凱里·漢德並不像之前二位認為的,藝術家和策展人的角色有著變化的邊界,但是,除此之外,其對極具變化的協商過程的描述卻與前二者十分相似。

由誰掌舵?

似乎不管是何種實踐——“策展人”的、“藝術家策展人”的抑或是“利用策展方式創作的藝術家”的——其中的關係總是不固定的,總是可以被重新解讀和變化的。但是,在所有這些例子里,策展人按理說總是掌控著分配大權,因此這個權力基礎是幾乎無法動搖的。

“當組織或者個人選擇藝術家進行合作,鑒賞能力和藝術價值確定的問題依舊是複雜的,不管他們是‘藝術家策展人’還是‘藝術家主導的組織’。那些掌控調節、分配、可見性機制的人和那些沒有掌控特權的人之間的關係自然就形成了權力高低的地位”--凱利·拉奇

然而,這種權力關係並非壞事。如凱里·漢德所說,“平等”是不合時宜的,不可能的概念——想想分配和可見性結構的重要性便不言自明了。這三個例子都說明了和諧並不是最重要的,實際上一定層度的掌控和專業見解是關鍵的,否則便“無人掌舵”,這樣一來項目便沒有方向和結構。對藝術家和策展人而言,艱難的關係並不一定會導致不好的項目,但是樂意對話確是最大化溝通效果的契機。也許,把這種關係看成是觀點的碰撞(而不是‘掌舵人的碰撞’!),而不是觀點的溶解,確實更可能帶來令人興奮的結果。這裡沒有一位“策展人”認為他們會簡單地把空間或者機會給予藝術家——在他們的描述中,這都是一段更具活力的關係,在其中他們自己的因素都對結果起著重大的作用。或許他們是要有人證明自己的信念,利用他們的力量去傳達他們認為重要的東西——這種想法也是很重要的一點。

像科爾斯頓這樣“從事策展人工作的藝術家”和領薪的策展人如凱里·漢德相比,她們的做法以及和別的藝術家之間的關係似乎並無特別的不同。利用策展方式創作的藝術家凱利·拉奇在相比之下就顯得更與眾不同,因為她甚少涉及協商的問題。“守門人”或“質量仲裁者”的身份在三位“策展人”身上都有不同程度的體現。他們活動的不同更多體現在對於藝術家和社區網絡的作用上,正如巴斯鮑姆一開始提及的。但是,或許把科爾斯頓或者凱利、凱里的活動與一種規範作衡量對是文不對題,我們更感興趣的是其中不斷發展的動態關係,及其如何形成由策展人和藝術家共同促成的新作品。或許我們正愈發意識到,藝術從來就不是單個人創作出來的(8)。在利物浦靜態畫廊(Static Gallery)的一次討論中,皮特·克拉克(Pete Clark)(9)指出“尾巴搖狗搖得太厲害了”——意思是,我們給予策展人、寫手等等太多權力和職責讓他們在社會領域創造藝術家的作品。以前的觀點是,藝術家沒有策展人和寫手也可以,但反之就不行。權力結構當然是有問題的,但是如果到現在還不能意識到可見性結構確實構建了我們正在討論的作品,甚至是藝術,那才是荒唐的。我們所知道的藝術是一張複雜大網上各個演員各司其職的產品,我們對此認識越深入,利用得越好,對藝術便越好。

對於計程車畫廊而言,和藝術家的關係似乎與作品本身的地位相比,如果不是更重要,起碼也是一樣重要。這也許是因為計程車和社區的關係更受重視,又或是因為這種關係只涉及兩人——沒有機制可以調和這種關係,正如利物浦的藝術與創意科技藝術基金會(FACT)一樣。但是,比這更深遠的是,這種關係及其微妙之處正是藝術作品構建過程中與生俱來的。如果把每個計程車畫廊的展出都看作是一段不同關係的表達,那會是很有趣的體驗,計程車切切實實地提供了一個藝術家可以選擇居住、支配或者對抗的結構。似乎,在伯瑞奧德的基於“生產”藝術實踐的語境里,確確實實存在著使得“策展人-藝術家”關係及其權力關係得以承認並且在作品中得以清晰傳達的可能性。

- Transmutation by David Kefford

- Second Skin by Pamela Wells

- Jenkins T (2004) ‘Use it or lose it’ The Spectator, 7 February. p.35.

- Rosler M (2003) Someone Says…

The Next Documenta Should Be Curated By an Artist. Copyrights Jens Hoffmann and Electronic

Flux Corporation. http://www.e-flux.com/projects/next_doc/cover.html. - Gillick, L (1993) Curating for Pleasure and Profit. Art Monthly. June. P.15-18.

- Basbaum, R “I love ‘Etc Artists’’ The Next Documenta Should Be Curated By an Artist.

Copyrights Jens Hoffmann and Electronic Flux Corporation.

http://www.e-flux.com/projects/next_doc/cover.html - Basbaum. R“I love ‘Etc Artists’’ The Next Documenta Should Be Curated By an Artist.

Copyrights Jens Hoffmann and Electronic Flux Corporation.

http://www.e-flux.com/projects/next_doc/cover.html. - Gillick, L (1993) Curating for Pleasure and Profit. Art Monthly. June. P.15-18.

- Gillick, L (1993) Curating for Pleasure and Profit. Art Monthly. June. P.15-18.

- See Wolff, J (1981) The Social Production of Art. Macmillan, London.

- Pete Clark in (eds Shaw B and Sullivan P) (2003) EXIT REVIEW. Static, Liverpool.

Reference

- Bourriaud N (2001) Postproduction. Lukas & Sternberg.

- Gillick L (1993) Curating for Pleasure and Profit. Art Monthly. June. P.15-18.

- Hoffman J (2003)The Next Documenta Should be Curated by an Artist (including

- Basbaum, R and Rosler M (2003)

- http://www.e-flux.com/projects/next_doc/cover.html.

- Jenkins T (2004) ‘Use it or Lose it’ The Spectator, February 7. p.35.

- Static (eds Shaw B and Sullivan P) EXIT REVIEW. Static, Liverpool.

- Wolff J (1981) The Social Production of Art. Macmillan, London.

Becky Shaw 貝奇·肖

Becky Shaw has been making publicly commissioned artworks in the social realm since 1993. These works critically examine the relationship between the individual and the social, focusing on contexts of care, industry and education. The works sit within a tradition of process-based, or live art and involve scrupulous attention to context. Works have been commissioned by, or produced at organisations including Grizedale Arts, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art, In Certain Places, Air/Cocheme Fellowship, Hayward Gallery, ICIA, Sculpture Space Utica USA and Amstelveen Art Incentive Prize NL. In 1998, Shaw completed a practice-based doctorate, and between 2000-2006 she was co-director of Static Gallery, Liverpool. Shaw writes as part of her practice and as a means of exploring the wider visual art infrastructure. Dr. Becky Shaw is currently the postgraduate research tutor for the Art and Design Research Centre at Sheffield Hallam University.

貝奇·肖自1993年以來一直接受公開委託從事社會領域的藝術創作。她的作品批判地審視了個體與社會的關係,關注社會保障、產業和教育問題。其創作遵循基於過程或現場藝術的傳統,對語境有著細緻的洞察。她受眾多組織委託創作,同時也在許多組織中從事創作。這些組織包括:格裏茲戴爾藝術機構(Grizedale Arts)、塞恩斯伯裡視覺藝術中心 (Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts)、定點藝術(In Certain Places)、Air/Cocheme Fellowship、海沃德畫廊(Hayward Gallery)、ICIA藝術機構、美國尤蒂卡雕塑空間(Sculpture Space Utica USA)以及荷蘭阿姆斯特爾芬藝術激勵獎(Amstelveen Art Incentive Prize NL)。1998年,肖獲得了以實踐為主的博士學位,2000年至2006年,她是利物浦靜態畫廊(Static Gallery)的總監之一。作為藝術實踐的一部分,她也從事寫作,並將寫作視為一種探索更寬泛意義上的視覺藝術的方式。貝奇·肖博士目前是謝菲爾德哈勒姆大學(Sheffield Hallam University)藝術設計研究中心 (the Art and Design Research Centre)的研究生導師。

Kirsten Lavers 科爾斯頓·萊弗斯

A former nurse Kirsten Lavers studied at Dartington College of Arts graduating in 1991 and subsequently taught there on both the Visual Performance and Performance Writing degree courses. Kirsten’s work rarely appears in galleries and is always made in response to a specific site or public space often including photography, video, sound, performance as well as objects that she has made or gathered. Kirsten’s approach is collaborative, closely involving the people whose space she is responding to as well as other artists. In 2001 Kirsten installed a black London taxi cab in her front garden and for the next 8 years hosted a range of eye-catching exhibitions made especially for Taxi Gallery by over 30 national and international artists. Kirsten was neighbourhood artist for the Orchard Park housing development (north of Cambridge) working with the early residents on a number of projects including hand made road signs, an urban beach, and the commissioning of 8 artists to create a temporary art trail through the development . Kirsten has recently been involved with public art projects for Hundred Houses Society and the NW Cambridge Development. She is currently focusing on a series of live drawing projects entitled ‘Admitting the Possibilities of Error’.

科爾斯頓·萊弗斯當過護士,後就讀于達靈頓藝術學院(Dartington College of Arts)並於1991年畢業,畢業後她繼續在該學院任教,講授視覺表演(Visual Performance)和表演寫作(Performance Writing)學位課程。科爾斯頓很少在畫廊中展出作品,而是根據特定的展出場地或公共空間創作,其作品包括攝影、視頻、音頻、表演以及自己製作或收集的物品。科爾斯頓的創作強調合作,需要與展出空間的提供者以及其他藝術家緊密協作。2001年,她把一輛黑色的倫敦計程車置放於她的前院,在接下來的八年裡,她專門為計程車畫廊舉辦了一系列吸引眼球的展覽,參與者為來自本國及海外的30多名藝術家。科爾斯頓是位於劍橋北部的果園房產(Orchard Park housing development)的社區藝術家,與早期入駐的居民合作開展了一系列項目,包括自製的路標、城市沙灘,以及委託八位藝術家設計一貫穿園區的臨時藝術小徑。科爾斯頓目前正在參與“百家協會”(Hundred Houses Society)和劍橋西北部開發工程(NW Cambridge Development)的公共藝術項目。她當前正在進行的工作是名為《允許犯錯的可能》的一系列現場繪畫項目。

Find Out More: www.kirstenlavers.net

Other Views

“It was commented that artists can do without curators and writers etc, but not vice versa. Of course power structures are problematic but it is ridiculous to even speak of art today without recognising that visibility structures produce the work we examine . Art as we know it is produced by a complex web of actors and the further we go towards recognising and utilising this the better.”—Dr Becky Shaw, artist, research tutor at Sheffield Hallam University.

“以前的觀點是,藝術家沒有策展人和寫手也可以,但反之就不行。權力結構當然是有問題的,但是如果到現在還不能意識到可見性結構確實構建了我們正在討論的作品,甚至是藝術,那才是荒唐的。我們所知道的藝術是一張複雜大網上各個演員各司其職的產品,我們對此認識越深入,利用得越好,對藝術便越好。”--貝奇·肖博士,藝術家,謝菲爾德哈勒姆大學研究生導師。