Interview with Marko Daniel

專訪馬可•丹尼爾

EDITED BY 編輯 x MICHELLE YU 余小悅

TRANSLATED BY 翻譯 x BOWEN 李博文

Marko Daniel is Convenor of Public Programmes at Tate Modern and Tate Britain. In 2014, he was curator of the 8th Shenzhen Sculpture Biennale: We have never participated. He was co-curator of Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape (Tate Modern, 2011; Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona; and National Gallery of Art, Washington). He was curator of a solo show by Taiwanese artist Chen Chieh-Jen at Chinese Arts Centre, Manchester (2010) and Vice-Chair of the London Consortium, a unique collaboration between the Architectural Association, the Institute of Contemporary Arts, the Science Museum, Birkbeck College and Tate that offers interdisciplinary research programmes in the humanities. Marko Daniel is a member of the Academic Committee of OCAT Shenzhen. He completed his PhD on Art and propaganda: The battle for cultural property in the Spanish Civil War at the University of Essex in 1999.

馬可·丹尼爾是泰特現代美術館和泰特英國美術館的公共項目召集人。2014年,丹尼爾擔任第八屆深圳雕塑雙年展“我們從未參與(We have never participated)”的策展人;2011年,他是“胡安·米羅:逃亡之梯(Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape)”展覽的聯合策展人,該展覽在英國泰特現代美術館,巴塞羅納胡安·米羅基金會以及華盛頓國家美術畫廊進行巡展;2010年,丹尼爾為台灣藝術家陳界仁在曼城華人當代藝術中心的個展擔任策展人;他還是倫敦聯盟(London Consortium)--一個由建築聯盟學院、當代藝術研究學會、科學博物館、倫敦大學伯貝克學院以及泰特美術館聯合創辦的跨學科人文研究項目--的主席;丹尼爾同時也是深圳OCAT的學術委員會一員。他於1999年在埃塞克斯大學完成博士學位,課題是“藝術與宣傳:西班牙內戰中的文化財產之爭“。

ART.ZIP:How would you describe the current situation of artist, curator, and artist as curator in the UK now?

MD:It is a very interesting and complex question. I think the current notion of a curator has only come into existence in the last 20, 30 years. When I worked on my first exhibition project here in London in 1995, we were not called curators, but selectors; we used a completely different term. At that point, the curator was somebody who worked in a museum and looked after the works in its collection. So this “looking after” side was most important. This included research into the history of the object, but also physically looking after it, making sure it was in good condition, and knowing what its provenance was. At that point, somebody who worked on exhibitions was identified by reference to the fact that they chose works of art for a project and selection. Since then, the word ‘curator’ has become incredibly widespread.

About 10 years ago, Tate was very actively involved in a PhD programme here called the London Consortium, which was a collaboration between Tate and other institutions like ICA, Architectural Association, Birkbeck University of London, and subsequently the Science Museum. In that collaborative project, we realized that people were more and more interested in the notion of curating. People started curating things that were not art. First, in the museums, it was not just the people who were looking after the permanent collection, but also people who were making exhibitions. Then people who worked in the learning department were said to be curating events, they were curating the film programme, and it then extended from that.

Apple is perhaps the most famous brand because they started ‘curating’ Apps, so that when you go to the App Store it offers you a selection of Applications to use. In a way, computers began to curate an experience for you. It is a really interesting comparison actually with 20 years ago, say; if you wanted to see examples of video art, it was very, very hard to find anything. Finding them, getting physical access to that material required a lot of research and resources; you needed to travel to get it. Now if you want to see anything or hear any music, you can go online, it’s all there. So when you are growing up now, the problem is not how to get access to a blues song that was written in the 1930s, of which there are maybe one or two recordings. But actually now you don’t need to find the material, you need to find out what you want to listen to. So now what we are dealing with is the curation of knowledge.

Everything is actually much more easily accessible, and the most important thing now becomes how do you get access to it? What do you want? There is so much information that somebody needs to help you narrow down the selection. And that itself is the process of curation. As a context this is really useful because it allows you to think about the way in which we use the term ‘curator’ for people who have a specialist knowledge. For example, you might go to a particular blog, because the person who writes it selects really interesting songs. Now I could find the songs myself, but I wouldn’t know where to begin. So I go to that blog and I get a selection readymade for me.

We are looking at two different kinds of selection here, one is simply based on knowledge and research, and the other one is based on taste. The two kinds go together. What we are looking at when we are dealing with curation is different motivations for making a selection of works. So maybe this is the most significant difference between the ways in which professional museum curators work and artists who are also curators. What do they offer the audience that comes to their exhibitions? It is the way in which artists and, to a greater or lesser extent independent curators, bring their own sensibilities to the selecting of artwork.

But particularly when you come to institutions like Tate, one of the main goals that we have in curating is to help the work of the artist to become visible in the best possible fashion. So in an institution like Tate you are dealing with something that is quite different from the celebrity curator. Celebrity curators may sometimes confuse their role with being an artist themselves, as if their exhibitions were works of art by themselves. I think in institutions like ours, we tend to be very cautious about that, because we think the most important element to deal with is the work of the artist, and we need to show that to the audience as best possible.

ART.ZIP: The curator plays a very significant role in presenting artwork to the public, do you think in this case the curator has a certain kind of superpower in showing art to the world?

Many people believe that, and if I take this to the extreme you could say that whether something is art or not is decided by the curator. According to this very extreme version of this argument the institution of the museum has a great deal of power. In the caricature version, when we decide to put something on display as art, the artists should consider themselves lucky to be selected by Tate. I am caricaturing this position specifically because I don’t think it’s true.

From the 1950s onwards philosophers writing about art developed the “institutional theory of art” in which they argued that whether something is a work of art or not, does not depend on anything that’s inherent in the work. It also doesn’t depend on the efforts that the artist puts into making the work, or special attributes that the artist gives the work that they made. Rather, whether something is art or not depends on a collective decision by the art world to consider it art. It is a very powerful argument as well as powerful critique, because according to it ultimately there’s nothing essential in the artwork that really makes it art. If the artist, commercial galleries, museums, art critics, collectors, and the public all agree that it is art, then it is art. One of the problems with this theory is how do you become part of the art world? How do you make the decision whether something is art? It could be seen as a very self-referential theory.

Another criticism that could be made on the basis of the constituency of the art world is that you are practically looking at the whole world, because you are talking about the artist, the art gallery, the dealer, the museum, the art journalist, the art critic, the curator and the public. The moment you include everybody you are back to square one. To some extent, it quite accurately reflects where we are now, which is that there are many works of art which some people consider to be works of art, but other people might just simply turn around and say ‘I don’t agree, for me it isn’t a work of art.’ At this point you could ask ‘Does it matter?’ You could change the question around a little bit and say ‘what happens when you consider it as a work of art?’ If you consider it as a work of art, that can change the way in which you look at the world, that can change the way in which you think, change the way in which you are able to see other things in the world. I think this is a very useful way of trying to cut through this dilemma.

But to come back to your question, whether the curator has a superpower. The curator can’t just put anything in the museum, and people will not just come automatically and accept it. It’s not as simple as that. I think we have to assume that it’s a very complex eco-system, where, if you are making a proposition, saying ‘I want this work to be considered art’ and nobody agrees with you, and the public doesn’t come, then you’ve got a problem. You haven’t got a superpower. You only have the ability to work within a certain horizon of expectations. And within that horizon of expectations, you can try and change what the people think, and change what people consider art or not. Some people are very good at doing this slightly more radically than others, some people are very good at persuading others and presenting a good argument for why something should be seen as art, and get other people to see it. But sometimes it is a much bigger task, it is much more difficult; and other times you have something that becomes incredibly popular as an art form and then a few years later nobody cares about it anymore. So is there a simple superpower, a superpower that has permanent effects? No.

The way in which the artist sees the world, and changes the way in which we see the world, is really powerful. Curators are playing a secondary or even third level role to this.. That’s one of the most important things in this.

ART.ZIP: What’s your curating principle as an institutional curator?

I think research is incredibly important. Until very recently, maybe it’s still the case in major museums, to work in an institution like this you needed a university qualification that was research-based. I think curatorial studies programmes have only come into play quite recently, and the most important skill you need to have as a person working in a museum like this is the ability to carry out research, as it always underpins the work that we are doing. Here we have two main strengths in relation to art, one is the building of the collection, and the other one is the making of exhibitions. Both equally depend on research. You can not make a decision about which artist is in need of an exhibition, unless you are able to judge what the alternatives are. Why we would choose Marlene Dumas, for example, as an artist? What are the factors that go into making that decision? And so you really need to understand the global picture of art making, and you need to understand what the role of painting is in contemporary art. Why would we do a big solo show of an artist who paints now when so many others do not? And why her if we are looking at painting? All those factors ultimately are based on research, on the understanding of the international situation of the art world. Why do this at Tate? Other large venues in London like Hayward Gallery or Royal Academy of Arts, they do different kinds of exhibitions, always with research-based approach, but they have their own criteria for making decisions. What makes Marlene Dumas a really significant artist for us to show in relation to other art that is being made now and other art that has been made? In theoretical terms, I would talk about the synchronic and the diachronic. The synchronic means everything that’s happening at the same moment in time, so we need to see where the artist fits into the picture, and the diachronic refers the developments across time – historically, what are the historical developments that suggest that to show Marlene Dumas at this point is right.

We could unpack this a lot more, in terms of the way in which museums work internationally and in London, by thinking about what chance we have got of actually making an exhibition that the public wants to see. Because if we do a really significant exhibition of the artist and nobody is interested in it, if we can’t make that connection between the art that we put on show and the section of the public that we hope will come to see it, then we have a problem. So for Dumas, we are really, really happy that there are incredibly positive responses to the show. And sometimes we do some other exhibitions which are perhaps more difficult, where we know in advance that we will get a much smaller number of people coming to see the exhibition, but it’s still worth it, because of where the artist’s work fits at this moment in time and across time.

ART.ZIP: Do you see any limitations for an institutional curator?

I think for everybody who works in an institution there are tremendous advantages and sometimes also disadvantages. As an individual, you need to make the decision whether that is where you want to be, and whether that is what you want to do. In terms of the advantages, there are quite simply the resources, there are certain things you can do when working in an institution that are very, very hard when working independently. When you are working independently, you have to spend a lot of time trying to find partners and resources, the money for the next project. And when you do that, each of the partners you work with will have their own ideas, so you’ll find an institution saying ‘that’s a very good project, but can you do it more like this?’ or somebody who sponsored the exhibition will want to add their suggestions, so by the end of it your project is subject to constraints, even when you’re working independently. I think people sometimes romanticize the work of the independent curator in the same way that people romanticize the work of the artist: the artist is somebody who is completely free from external influence and works in his or her studio. That is obviously not the case, and it is not the case for an independent curator either. And for institutional curators of course, the institutional constraints are, to some extent, a given, so there’s a certain continuity that makes it sometimes easier to develop new projects. We also cannot forget the visibility, the resources and the responsibilities that come with working in a big institution. For me that is something I think about every day, I think all my colleagues are the same, we know that we work for a museum that has a big international standing and so when you make a decision about what to do, which artist to work with, you are always aware that you have the responsibility, in our case, to the people. In the British case, it is a very clear relationship: Tate is a national museum, and that means we are ultimately responsible to the public, to everyone. That means you need to think very carefully about which way you operate and I think largely that is a good thing because when you are faced with constraints, you ought to feel the responsibility to the people and you need to be able to defend the project.

This is not quite what your question started out as, but I often think that when you are working in an institutional context, whether it’s a freelance or as an employee of the institution, one of your main roles in working with contemporary art is to be an intermediary between the artist and the institution, with a view to making the project better. It is not to reduce the project or cut it down in response to institutional demand, but it’s to defend the concept, the idea and the realization of the project from the artist to the institution. And you have to mediate with the artist, so that by working with you they share the responsibility to the public. This is a very interesting aspect – how do you make sure the vision of the artist and the potential of the artwork is realized to the fullest in a particular context, where there are, as there always are, an apparatus, boundaries, and limits.

ART.ZIP: How do you perceive the evolution of curatorial roles at Tate?

I think you will be really interested to see what we do when we open the new building. Before I talked about the synchronic and the diachronic; in this context we are thinking about what is going on in the art world right now. We are thinking how we can connect what it is going on in the contemporary art world right now with the history of art, particularly with the history of art that Tate represents, throughout the collection. So what we are seeing now is really a normalization of globalization. Globalization a few years ago, a decade ago, was exciting and new and something we were struggling to get to terms with.

We are now in a situation that when we are talking about any kind of idea, it is almost impossible to think about it as something where we don’t automatically take an international and planetary dimension into consideration. So normalization is very important. When Tate Modern opened as a museum of international modern and contemporary art, we realized our collection was very much focused on European and North American art. So before 2000 – this is a little bit of exaggeration, although it is still surprisingly accurate description of what we had before 2000 – international art, meant European and North American. It was after 2000 that we realized we had many gaps in our knowledge that we needed to address and fill and we’ve worked hard on that. So when the new building opens, we really want to try and show you how a normalization of globalization can happen. We do not make a “special” case for it, we don’t say, “look, there’s a Brazilian artist, oh, that’s so exciting”. No, there is a Brazilian artist because a Brazilian artist was making the most significant work in that context. And we display Japanese artists, Chinese artists over there, because they were the ones who made the most significant work in that area. Not because there is an exotic excitement about that, but because that is actually the fact. You could also talk about it as the fact of globalization rather than the desire of globalization. I think 15 years ago we were talking about something that was much more an exotic desire and now we are talking of something that is more of a fact.

ART.ZIP: What do you think of the relationship between artist and curator?

I’ve worked with historic exhibitions, like the Miró exhibition, where the artist is no longer alive, so you yourself, through research, need to make sure that you represent the work of the artist fairly, accurately and correctly. And then within that you can give rein to your curatorial curiosity and creativity, and try to show the work in a way that helps the understanding and experience of the work, but it needs to be tight, very solidly about facts.

When you are working with contemporary artists, the situation is very different, because the artist is there, and you work in partnership with them. As a curator working in partnership with an artist, you really need to think about what the project is, what you are really trying to achieve, and how you can best achieve that. So for me, depending on the context in which you work, you will need to find different ways of helping the project become realized. On a conceptual level, my role is to make sure the exhibition project is as clearly communicated to the artist as possible and that there is a dialogue between me and the artist about their work and, particularly in a new commission, how that work is developed. The artist obviously has to have the final say, that is very important. So your role is very much about engaging in conversation and negotiating with the artist, while at the same time it is about negotiating with all the external factors, whether you are making the work for a biennale, or for a small exhibition, or as a work that appears in public, somewhere in a park, in a square, in a shopping centre or the top floor of a car park, it could be anywhere. You need to think about the relationships. So it is very much about becoming aware of multiple relationships that you channel between the artist and all the other stakeholders in this relationship.

There is another really interesting aspect to the relationship when you are working with a contemporary artist, but you are working with pre-existing work. I think there are different approaches where sometimes the curator can be in danger of having an idea or a concept for an exhibition and they look to artists for ways of exemplifying their concepts. So for me there is a question of priorities there. If you have such a strong idea that you practically think your idea is a work of art and you use artworks almost as your raw material, I don’t like that. I think that is not respectful to the artwork or the artist.

I am keen on developing a way of working with the artist, where the artist feels the particularity and significance of their artwork is respected. Say I select three artists as the most significant ones in relation to a curatorial concept but the more I study their work, the more I realize that my concept doesn’t quite fit, then my concept is wrong, and I need to adjust it. You could almost think of it as a kind of dialectical process. I have an initial idea, I go to artists, test my initial idea and I realize my idea needs to change. I bring more artists in, and then my concept needs to constantly tweak a little more. So if I think about the way in which an exhibition comes together in the process of discussing and working with artists, I realize that by the time the exhibition opens, it is the exhibition and concept that has emerged out of the process of working together. If I started from the same initial idea the following day and talked to different artists, the exhibition and concept would end up being different, because they are mutually co-developed. I think that is a really interesting process.

ART.ZIP: In terms of audience development what do you do as a curator to help audiences to understand the work?

Due to my own background, because I come through the public programmes team of Tate, working with the public is really important. I think the way in which the public has a role to play in the experience of art is absolutely essential and that happens on many different levels. To some extent you could talk about the expectations of interactive or participatory art practice where the audience are actively involved in the making of art, the realization of the art, but I think we don’t have to go to that extreme, because it is equally significant in all projects. In terms of the way in which the exhibition as an organism communicates with the audience it is about the way you design spaces, it is about the way that language provides information, through labels and texts, and other ways of making the experience of the works of art and the exhibition itself part of the curatorial work. So on one hand you have the experience of the individual work of art, which is normally determined by the artist. It sets certain parameters; for example the artist will have an idea of how that should be done, it could be in the most general terms that ‘I made a painting and we hang it on the wall, you look at it’. But even with this very basic example, there are many different ways in which that experience could be structured. And then on a bigger scale there is the question of the experience of the exhibition as a whole, with all the other dimensions to it.

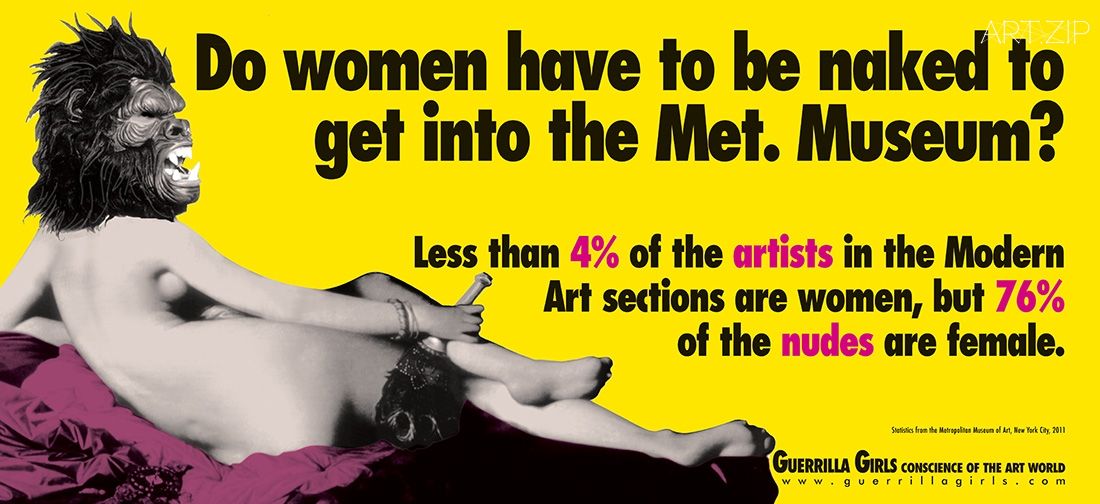

8. What steps is Tate Modern making to address the gender imbalance of their collection?

I should start with an anecdote: the first month I worked at Tate was in 2006, and I worked with the American activist group the Guerilla Girls. They did a workshop here with us and they wanted to talk to young artists who were interested in making works like them. It was a great project, and we had their work on display in the galleries, and they wrote and said, “we want to run this as a master class.” I thought, the language was very gendered, very male and was surprised as they are so much more radical than that. Calling it a master class seemed very old-fashioned. They said, “you have to call it a master class, all the posters have to say master class.” And I thought, they are weird. Then the day before the master class, they came into the gallery, wearing black clothing with their gorilla masks on, and they had these big felt pens for graffiti and went through the entire building and crossed out the word master and wrote mistress on every poster for the workshop. So they set us up. Of course what they were really interested in at that point was exactly that they were concerned about the way in which art collections are overwhelmingly male. The fact is, over the last few years, we have tried to address this, we are trying to address this in a way without making a song and dance about it. We want to promote women artists, we want to make exhibitions with really good artists and we hope that we can achieve a much better balance. And while, for example, last year, we had Malevich, Matisse, Polke, all men, this year it is all women, we’ve got Dumas, we’ve got Agnes Martin and Barbara Hepworth coming up, you don’t have to have balance at every point, but it needs to work out over time.

ART.ZIP:對你來說,英國的藝術家、策展人以及藝術家策展人這三種身份的現狀如何?

MD:這是一個非常有趣而複雜的問題。我清楚策展人是在過去二三十年內出現的年輕專業。我在1995年於倫敦進行了我的第一个展覽項目,那是二十年前的事情了,那時我不被稱作是策展人,而是“選擇者”-所以在過去我們使用了完全不同的辭彙。在那個時候,策展人在博物館內工作,負責照看藏品。所以,“照看”工作就是最重要的工作,我們需要對於藝術品或文物的歷史進行研究,但同時需要照看它們,確保它們保存良好,了解它們的出處,並好好地照看這些物件。在那個時候,在一個展覽之中工作意味著:你手頭上有很多的藝術品,而你要選出你希望放到一起去展示的那些,而這就是當時工作的標準。自那時開始, “策展人”一詞便被大量地傳播開來。

大約十年前,泰特美術館開始積極地參與名為倫敦聯盟(London Consortium)的博士學位研究項目,這個項目的合作者包括了泰特美術館、當代藝術研究學會(ICA)、建築聯盟學院(Architectural Association)、倫敦大學伯貝克學院(Birkbeck University of London)以及隨後加入的科學博物館(Science Museum)。在這個合作項目中,我們意識到人們對於策展實踐越發感興趣。人們開始為不屬於藝術範疇的事物策劃展覽。首先,在美術館中,不僅那些照看永久藏品的人們在進行策展,為了展覽計劃而工作的人們也開始進行策展工作。隨後,在教育部門工作的人們也開始策劃活動,包括電影放映等等。策展實踐因此得到發揚。

Apple可能是最著名的品牌,因為它們開始了對手機應用程序的策劃,在Apple的手機應用程序商店上你可以找到一系列經過挑選的應用程序供你使用。計算機開始為你策劃經驗。這事實上是一個非常有趣的比較:打比方說,在20年前,如果你想要看甚麼影像藝術作品的話,無論是在電視上或是在影院中那都是非常非常困難的事情。你需要找到這些作品,而找到這些作品,將它們拿在手中之前你已經需要完成一系列的調查、研究,也需要很大量的資源,你可能需要長途跋涉地去尋找這些作品。在今天,如果你想要聽音樂的話,所有的一切都在網上。所以,在現在,在一個人的成長中,問題不再是如何能夠聽到一首20世紀30年代寫就的藍調歌曲,儘管這首歌可能只有一個或兩個實體拷貝。問題變成了:你需要弄明白,這到底是不是你想要聽的。所以我們現在需要應對的是知識的策展。

簡言之,所有事物都越發唾手可得,而重要的問題則變成了獲得這些事物的方式以及你到底想要些甚麼。在信息爆炸的時代,你需要別人的協助來完成自己的選擇。而這本身就是一個策展的過程。我覺得這裡對語境的描述是很有幫助的,因為關於這個時代背景的描述能夠幫助我們思考我們使用“策展人”這個詞的方式-用以形容有着某種知識特長的人。再打一個比方:我可能會常去看某個博客,因為博主總能向我推薦一些特別有趣的歌曲。儘管我也能找到這些歌曲,但我並不知道應當從何聽起。所以我前去關注這個博客,去接受這個由別人完成的選擇。

然而,我們在討論的事實上是兩種選擇:一種是簡單的、基於知識以及研究完成的選擇,而另一種是基於品味完成的選擇。這兩種選擇密不可分。當我們在進行策展實踐的時候,我們在討論的是不同的藝術作品選擇原則。對我來說,這可能是美術館策展人、獨立策展人以及藝術家策展人之間最大的區別:他們為前來觀展的觀眾提供了些甚麼?藝術家作為策展人在選擇參展作品的時候會帶入他們的藝術感性,而一個獨立策展人或多或少也會這樣做。

但當我們要面對的是泰特這樣的一個機構的時候,策展實踐的一個主要的任務是幫助藝術家以最好的方式將他們的作品呈現給觀眾。在泰特之類的機構中,我們的立場和明星策展人不一樣,明星策展人通常被混為藝術家來對待。他們可能會認為,他們的策展實踐能為作品增添一些別的甚麼,並非來源於作品本身的東西。我認為,在我所供職的泰特美術館之中,我們傾向於謹慎地處理這種態度,因為我們認為最重要的元素是藝術家的作品,而我們需要以最好的方式來呈現這些作品。

ART.ZIP:策展人在對公眾呈現作品的過程中扮演了一個很重要的角色。你覺得在這樣的環境中,在向世界呈現藝術作品的過程中,策展人是否有着一種巨大的權力?

ART.ZIP:策展人在對公眾呈現作品的過程中扮演了一個很重要的角色。你覺得在這樣的環境中,在向世界呈現藝術作品的過程中,策展人是否有着一種巨大的權力?

MD:如果我把這個論點推向極致,我們可以說,很多人相信,一個物件算不算是藝術品是完全由策展人來決定的。這是這個論斷的極端說法,這個說法也包括這個看法:美術館機構在決定把甚麼物件當作藝術來展示的時候有着極大的權力;如果泰特選擇展出哪個藝術家的作品,那個藝術家應當感到“非常幸運”。我在誇張地形容這個狀況,因為我並不認為這是事實。

我想,自20世紀50年代以來,討論藝術的哲學家們發展了被稱作“制度藝術理論”的嚴肅理論。這理論聲稱,一個事物究竟是不是藝術不是由其本質決定的,不是由藝術家的創作決定的,不是由藝術家賦予事物的特殊屬性而決定的,而是由藝術世界的集體考慮所決定的。這是一個非常有力的論點,也是一個有力的分析,因為,到最後,藝術作品中並沒有甚麼特殊的本質性區別因素。如果藝術家、商業畫廊、美術館、藝術評論、收藏家以及公眾都認為這是藝術,這就是藝術。然而這個理論的其中一個問題是,你如何能夠成為藝術界的一分子?你如何能夠為一個事物是否是藝術作出決定?所以這理論看起來只是一個自我循環的圈。

我們也可以從另一種角度批評這種理論:如果你要考慮的是所有可以就這個問題提出意見的人的話,你要考慮的就是全世界。因為你要考慮藝術家、畫廊、藝術品商人、美術館、藝術媒體、藝術評論、策展人以及公眾的所有意見。在你要考慮所有人的意見的時候,你就幾乎回到了原點,沒有任何進展。

在某種程度上,這比較準確地反映了我們現在的狀況,即,現在有很多的藝術作品得到了一部分人的認可,但另一部分人可能轉身離開,口中聲稱:“我不同意,對我來說,那不是藝術作品”。在這個時候,你可以提出這個問題:“這是不是藝術作品,是一個重要的問題嗎?”你也可以對問題稍作改變,提出:“如果你把它當作藝術作品,那會怎麼樣?”如果你簡單地說,好吧,藝術家把這件東西帶到這個世界上,而我們在一個畫廊中觀察這個事物,但你仍不能確定這是不是藝術作品。然而,當你把這事物當作藝術作品來對待,這時你的世界觀就發生了改變,你的思想發生了改變,你觀察世界上其他事物的方式也得到了改變。我認為這是超越這個困境的有效方法。

回到你的問題:策展人是否有着巨大的權力?我們可以輕易地說明這並不是事實。策展人不能在美術館空間內扔進隨便甚麼東西,人們也不會自動地前來觀賞。這沒有這麼簡單。我們需要承認,這是一個非常複雜的生態系統,這裡有着一種生態學,如果你提出,“我想要把這事物視作藝術”而沒有人同意、公眾也不前來的話,那你就有問題了。你並沒有巨大的權力。你只有在一個既定的認可範圍內進行實踐的能力。在這個認可範圍內,你可以嘗試改變人們的想法,並改變人們關於眾事物是否是藝術的想法。我一定不會否認,有些人能夠更好地完成這个工作。有些人非常擅長說服他人,並很好地提出為“為甚麼這個事物可以是藝術”的論點,而人們隨之開始關注該事物的發展。然而,有的時候,這是更大的一個問題,非常困難,有時候會突然出現大量的特定新藝術形式,而過了幾年之後沒有人再去關心這種藝術形式了。所以,關於策展人是否有着巨大的、永久的權力,我的回答是否定的。

在藝術家的世界觀中,策展人有着次要或者更低的重要性。而藝術家改變了我們觀看世界的方式,這是非常重要的。這是藝術世界中最重要的事。

ART.ZIP:作為一名機構策展人,你的策展原則是甚麼?

MD:我認為研究工作是非常工作的。最近幾年有了一些改變,但是在過去-在一些重要的美術館內仍然是這樣的-你需要有一個以研究為基礎的高等學位才能在一個像泰特的機構之中工作。我知道關於策展實踐的大學專業是在最近幾年才興盛起來的,而對於美術館工作來說最重要的技能就是研究技能,這總是我們工作的中心。這技能對於泰特之類的美術館來說無比重要。我們有兩個主要的工作:建立館內藝術作品收藏,以及進行展覽。這兩點是同樣重要的,如果你不能夠了解所有藝術家的重要性,你就無法決定到底要為哪位藝術家舉辦展覽。舉例來說,為甚麼我們要為瑪琳·杜馬斯(Marlene Dumas)舉辦展覽?甚麼樣的因素影響了這樣的決定?所以,你必須要了解世界範圍內藝術創作的狀況,你需要了解繪畫在當代藝術中的角色。為甚麼我們要在現在,當大部分藝術家都不再進行繪畫創作的時候,為一位繪畫藝術家舉辦大型個人展覽?如果我們想要聚焦於繪畫的話,為甚麼選擇她?所有這些因素都是與研究工作有關的,都是與關於全球藝術世界的理解有關的。為甚麼要在泰特美術館進行這樣的展覽?倫敦市內的其他大型機構包括還沃德畫廊(Hayward Gallery)以及皇家藝術學會(Royal Academy of Arts),他們舉辦不同類型的展覽,有着不同的判斷標準,然而他們也是大量地依賴研究工作的。與其他現在在進行創作的藝術家相比,甚麼讓瑪琳·杜馬斯脫穎而出?這總是與某些理論相關的,我現在希望談談共時性(synchronic)以及歷時性(diachronic)兩點。共時性的討論要關照在一個時間點內發生的所有事情。所以我們要去察看這位藝術家在當下這個時刻中的位置。而歷時性的討論則意味著在時間長河中的發展-過往的歷史中,有甚麼能夠告訴我們,瑪琳·杜馬是目前正確的選擇。不僅僅是正確的選擇,我們需要基於許多實際的因素進行決策-美術館的國際運作狀況、美術館在倫敦市內進行的工作狀況、以及我們完成這樣的一次大型展覽的契機等等。

因為,如果我們去做一個沒有甚麼人感興趣的藝術家的大型展覽,如果我們不能在藝術與特定觀眾之間建立聯繫,那就是一個大問題。所以,杜馬斯的展覽能夠獲得廣泛好評,我們真的感到非常非常高興。在另一些時候,我們進行著一部分很困難的策展實踐,因為我們在最初就知道,展覽只能吸引少量的公眾。但是那仍然是值得的,因為該藝術家的作品在當下以及在歷史中都是有着重要位置的。

ART.ZIP:你覺得機構策展人身份帶來了甚麼局限性嗎?

MD:我認為,對於所有在美術館機構之中工作的人來說,這份工作同時意味著很大的便利以及許多制約。對於個人來說,你需要弄明白這個機構是否是你想要為之付出的地方,這裡的工作對你來說是否理想。在機構工作的優點是,這裡提供了很多資源,在這裡有着很多作為獨立策展人很難能夠獲得的資源。作為一名獨立策展人,你需要花費大量的時間尋找合作夥伴、資源、為了下一個項目去尋找資金支持。然而,當你在這麼做的時候,你的每一個合作夥伴都有他們自己的想法。所以一個機構可能會說:“這是一個非常好的項目,但是你能不能這樣做呢?”他們又說:“噢,不行,這次展覽的贊助方希望這樣做。”在最後,就算你是獨立於機構外,你的項目還是受到了多方面的制約。我覺得,人們有時過於浪漫地想像一個獨立策展人的工作,就像他們會過於浪漫地想像一個藝術家的工作一樣:藝術家是完全不受外部制約的人,而他或她工作室的創作是完全不受外部世界影響的。

無論是藝術家或是獨立策展人,他們的現實肯定不是這樣的。對於機構策展人來說,制度性的制約幾乎是一種先決條件,所以反而有着一種穩定性,讓工作的開展變得更容易些。我們也不能忘記在一個大型機構中工作帶來的曝光度、資源以及責任。對我來說,這是我每天都在惦記的事情,而我想我的同事一定也都是這樣想的:我們在為一個有着非常重要的國際地位的機構工作,因此當你在作出一個選擇的時候-比如選擇合作藝術家的時候-你總要清楚你對於公眾有着重要的責任。

在英國,這是一個非常明晰的關係:泰特是一個國家美術館,而這意味著在最後我們是對全世界公眾負責的。這意味著,你需要非常仔細地考慮自己的行為,而對我來說這是一件好事,因為在面對制約時你應當了解自己的責任,你真正地感受到了你對於公眾的責任,而你也需要捍衛自己在進行的項目。

這已經偏離了你的問題,但我經常想,當你在一個制度語境內為當代藝術工作時-無論是獨立於機構之外還是受雇於某機構-你的一個主要角色是成為藝術家與機構之間的聯繫,讓工作項目變得更好。在面對制度要求時,你不能削弱或全盤否定一個項目,而需要捍衛來自藝術家的理念、概念以及項目的實施過程,你也需要為藝術家進行協調。他們在與你工作時也與你分擔了面對公眾的責任。在制度、邊界以及限制內你如何能夠保證全面地實施藝術家的理念以及藝術作品的潛力-這是一件非常有趣的事。

ART.ZIP:你是如何看待在泰特之中策展角色的演變的?

MD:我想你會對我們的新場館充滿興趣的。因為,這是我們構思了許久的計畫。在剛才,我討論了共時性和歷時性,而我們也要討論,現在的藝術世界之中究竟發生了甚麼?我們要考慮如何把當代藝術世界之中發生的事件與藝術史聯繫起來,尤其是與泰特美術館的館藏所代表的藝術史聯繫起來。我們現在正在目睹的,的確是全球化的常態化。在幾年前或幾十年前,全球化是讓人興奮的、新鮮的,那時的我們也在艱難地與之相抗衡。在現在,無論我們在討論甚麼理念,我們不可能不把這個理念放入全球化的語境之中去考慮。因此,這種常態化是非常重要的。歷史上,泰特的建立是一種非常重要的事件,而在今天,在建立泰特新館之時,我們意識到泰特的館藏不足以支撐這個新館,因為我們的館藏非常集中地代表了歐洲以及北美藝術。因此,稍帶誇張地說,在2000年之前,國際藝術意味著歐洲以及北美藝術。在2000年後,我們意識到,我們的知識體系有着許多需要彌補的不足,我們也需要為之付出許多努力。因此,在泰特美術館新館開幕之時,我們希望向你們呈現,全球化的常態化是如何發生的。我們想要包羅萬象,我們不會將視線聚焦於任何一個地區。我們不會說:“看,這是一個巴西藝術家,噢,這是多麼有趣啊。”我們會關注一位巴西藝術家是因為巴西藝術家在某個時期帶來了最具影響力的作品。我們也可能會關注日本藝術家,中國藝術家,因為他們在某個領域有着很高的成就。我們不會因異域風情而歡欣鼓舞,我們只因為事實上他們的作品很重要而關注他們。我想,在15年前,我們大量地在討論有關異域風情的慾望;現在,我們在更多地考慮事實。

ART.ZIP:你是怎麼看待藝術家與策展人的關係的?

MD:我參與過歷史性的展覽-比如米羅(Miró)的展覽-在策劃這些展覽之時,藝術家已經不在人世了,所以你需要通過研究確保你能夠公正地、精確地以及正確地代表這個藝術家的創作生涯。在這個框架中,你可以自由地發揮你在策展實踐中的好奇心以及創造力,並嘗試以一種幫助理解的方式呈現這些作品,但這種呈現方式也必須是嚴謹地、實在地與事實相聯繫的。

與當代藝術家工作則又是另外一回事。因為藝術家得以與你密切地溝通,他們的觀點就非常明顯了。作為一名策展人與藝術家協作時,你必須清楚自己想要完成一個甚麼樣的目標,以及清楚甚麼是最好的工作模式。對於我來說,基於不同的語境,你需要嘗試發現不同的、有效的工作方式。

在理念層面,我的角色是要確保展覽理念盡可能地與藝術家溝通清楚,我在與藝術家進行對話,來討論他們的作品,特別是他們在新的委託項目中的藝術創作是如何發展的,等等。藝術家有着最終決定權是一件很重要的事。所以,無論工作語境是雙年展、小型展覽、公園內的公共空間、廣場、商場或是一個停車場的頂樓-無論你在甚麼環境中工作,你的工作職責都是與藝術家進行溝通,協商,同時也要與所有外部因素相協商。你需要考慮這些關係。你的工作重心是對所有由你帶領至藝術家的關係保持意識,並關照這關係中的所有其他關連者。

這個關係中的另外一件有趣的事是,當你在與一個當代藝術家合作的時候,你同樣在面對既有的藝術作品。我知道在很多情況下策展人都可能進入到一個危險的境地:策展人有一個展覽理念,而他嘗試從藝術家的作品中尋找闡釋這個理念的方法。對於我來說,這是一個有關優先值的問題。如果你覺得自己有一個特別棒的點子,這個點子本身幾乎就是个藝術品,而你因此把別人的藝術作品當作創作材料來使用-我不喜歡這種工作模式。我覺得這是一種不敬的做法。

我在進行策展工作時,我希望發展一種與藝術家合作的方式,以讓藝術家感到他們作品的重要獨特性得到尊重。因為這真的很重要。作為一名策展人,如果我因為某個主題嘗試展出某件作品,而藝術家同意的原因是想要在某個雙年展中出現,而並不是作品本來就俱有這個含義。那是錯誤的,這不應該發生,我也認為很多藝術家不會認可這種事情。舉例說明,我覺得合適的策展方式是:我有一個概念,認為這三個藝術家是最合適的,然而隨著我的研究工作的進行,我意識到我的概念與他們的作品不符,我就應當承認我是錯的,我應當修正我的概念。我覺得這是正確的溝通和有意義的對話,你甚至可能說這裡有着某種辯證的過程。即:我有一個初步的想法,我去徵詢藝術家的意見,測試我的初步想法,並意識到我的初步想法需要修正。當我引入更多藝術家時,我的想法就更應再作適當調整。如果我認為展覽是以與藝術家對話或共同協作的過程為基礎的,那麼展覽的最終呈現則會體現這種共同合作的過程。但如果我一開始就確定一種觀點,然後帶著這種觀點和不同的藝術家對話,那麼展覽的呈現和概念也會發生變化,因為他們都是共同發展的。我認為這是非常有意思的過程。

ART.ZIP:在進行公眾拓展工作的時候,作為一名策展人,你是如何幫助觀眾理解藝術作品的?

MD:對我來說,這是一個很重要的任務。這可能也與我的背景有關-我供職於泰特美術館的公共項目部門。對我來說,與公眾溝通是非常重要的工作。我覺得公眾在藝術體驗的多個層面中扮演的角色非常重要。在某種層面,你可以嘗試進行互動或參與性藝術實踐的“極端化”,以鼓勵公眾積極地參與進藝術創作以及藝術實現之中來。但我覺得我們不需要那麼極端,因為公眾的角色在所有項目中都是同樣重要的。策展人的部份工作包括為展覽-作為一個有機體的展覽-與公眾的流暢溝通去設計空間、提供信息、標簽、文字以及進行其他能夠創造展覽體驗的工作。一方面你需要創造關於單一作品的經驗,這一般是由藝術家決定的。藝術家會有一些想法,比如:“我創作了一幅畫,我們把它掛在牆上,你來看。”就算是這麼直接的一個過程,也可以以許多的不同方式來進行經驗構建。在更廣大的層面來說,我也要考慮一個展覽中的眾多方面共同帶來的經驗。

ART.ZIP:泰特美術館在通過甚麼方式改變其館藏的性別不平等問題?

MD:或許可以從一件軼事說起:2006年我在泰特工作的第一個月,我和美國的行動主義團體游擊隊女孩(Guerrilla Girls)一起合作。我們一起在泰特進行一個工作坊,她們教授其他年輕藝術家怎麼創作像她們一樣的作品。這個項目非常有趣,而我們也在畫廊展示了她們的作品,她們特別要求說:“我們要辦一個大師班(master class)。”當時我心想,這用詞也太奇怪了,“master”這個詞非常男性化,像她們那麼激進前衛的人怎麼會這麼強調呢?因為叫作大師班實在是很落伍的叫法。她們堅持道:“一定要叫大師班,所有的海報都必須這麼印。”這實在太詭異了。然後在工作坊開始的前一天,她們穿著一身黑衣,戴著大猩猩面具,手拿塗鴉筆來到畫廊,把整座大樓的海報上的“master”全部打叉,寫成“mistress”。這一切都是她們預先設計好的“局”,她們當時反抗的正是藝術品都成了男性藝術家的專利,這是十分有趣的一個案例。事實上,在過去幾年裡,我們不斷地想要證明我們並沒有“重男輕女”,但我們不會採用大張旗鼓的方式來強調。我們想要推廣女性藝術家,我們努力和優秀藝術家一起合作辦展,我們希望能取得更好的平衡。舉個例子,去年,我們的展覽有馬列維奇(Melevich),馬蒂斯(Matisse),波克(Polke),全部都是男性藝術家。今年都是女性藝術家,有杜馬斯(Dumas),艾尼斯·馬丁(Anges Martin),芭芭拉·海衛夫(Barbara Hepworth)。我們需要長時間地去調整達到平衡,但不需要所有的事情都那麼強調。

Quotations:

When I am in China, I am always struck by the different ways in which people respond to art. One very positive thing is the belief which comes across from many people that contemporary art is meaningful, and it can actually make a difference. I would consider that to be a really important motivation. It would be far too easy to say that being an artist means that you are a painter and you produce very large paintings or very large sculptures and you become rich. It would be such a simplistic understanding of what the art world is, also of the way in which art impacts on people and seeing that people believe in the power of art is inspiring.

For me from the very beginning, art has always worked as two-way communication, or communication with many people, it is not just about a simple relationship between the owner of work of art and the use that they make of it, art has a much wider impact than that. In Europe, where art was used from the middle ages in churches, or from the nineteenth century onwards in public galleries and public places, there is a sense that art is meant to be seen by the people, you can see it for free, without having to own it, and that is really important, I think that’s really significant.

A museum in particular is both a place of production of knowledge and the production of art, but also a place of dissemination and of making public the most contemporary knowledge, the newest kind of knowledge as well as more historical development. So we are always looking back at history and finding new paths through history.

“在中國,我總是被人們對藝術的不同反饋而打動,其中一個非常積極的方面是許多人相信當代藝術是有意義的,是能改變世界的。我認為那是當代藝術非常重要的動力來源。有時候人們太容易斷定藝術家創作大型繪畫或雕塑是為了並能夠變得富有,這是對藝術圈、藝術影響力的一種粗淺認知。”

“對我來說,藝術從一開始就是一個雙向溝通,又或是多人溝通。藝術不是關於藝術品擁有者及其使用的簡單關係,藝術有比這更大的影響力。在歐洲,中世紀時藝術在教堂裡出現,19世紀開始就在公共畫廊和公共空間出現,因此我們可以看出藝術的本意就是讓人觀看的,你不必擁有它,你可以免費欣賞它。這才是重要的。”

“博物館是一個知識生產和藝術生產的地方,也是向公眾傳播最當代的知識的地方,無論是最新的知識還是歷史發展知識。我們總是在回顧歷史,並通過這樣的歷史回顧來尋找新的方向。”