Text by: Honour Bayes 撰文:Honour Bayes

Translated by:Li Bowen 翻譯:李博文

“I think in British theatre there’s been an ongoing problem of what to call things that aren’t plays because it doesn’t seem to be enough to just call it theatre. So there’s been a steady trickle of names; alternative theatre, physical theatre, experimental theatre but none have actually been right. But the visual theatre tag points to that very explicit challenge to literary theatre, to the idea that meaning in drama or in theatre is primarily carried by words, and that came in the 1970s and 1980s.”

──Tim Etchells, Co-Artistic Director of Forced Entertainment.

“我認為,在英國戲劇行業內,有個存在了很長時間的問題:我們不知道要如何去討論那些不是話劇(Play)的作品,因為稱那些作品為劇場作品(Theatre)是遠遠不夠的。因此我們使用了一系列名稱:“另類劇場(Alternative Theatre)”、“肢體劇場(Physical Theatre)”、“實驗劇場(Experimental Theatre)”等,其實沒有一個是對的。但產生於1970或80年代的“視覺劇場(Visual Theatre)”一詞直接指向了對“文本劇場(Literary Theatre)”的挑戰,挑戰了認為戲劇或劇場意義主要存在於語言中的概念。”

──蒂姆·艾秋斯(Tim Etchells),富斯德娛樂公司(Forced Entertainment)藝術總監

The British theatrical tradition is a famously literary one. From Shakespeare through to John Osborne and then the writers of the In-Yer-Face generation playwrights have ruled the roost. But for the last 40 years a revolution has been bubbling up against the tyranny of text.

From the 1970s companies have begun to experiment with a more physical form of theatre. They wanted to get away from the restraints of realistic and naturalistic drama and create an energetic visual style that combined strong design with choreography and physical imagery.

From the 1970s companies have begun to experiment with a more physical form of theatre. They wanted to get away from the restraints of realistic and naturalistic drama and create an energetic visual style that combined strong design with choreography and physical imagery.

Some companies and artists took inspiration from the world of fine art. Geraldine Pilgrim and Janet Goddard from company Hesitate and Demonstrate believed in the principle of creating work that could not be sold in galleries, that was live, of the moment and ephemeral. They explored the aesthetic of a highly visual style of performance where the central protagonists were always female.

受到菲利普·格里(Philippe Gaulier)及雅克·勒科克(Jacques Lecoq)等大師影響,包括同夥劇團(Complicite)的各團體發展了他們的風格,重新演繹了經典戲劇文本,並與編劇合作創作了新的作品。

在1980以及90年代,福斯德等劇團嘗試創造一種劇場形式,以反映20世紀末各藝術風格的碰撞以及圖像的轟炸。《法律中的困惑(Some Confusions in the Law)》及《關於愛情(About Love)》等作品也表達了對於後撒切爾時代暗淡圖景的意見。另一方面,康沃爾的虹彩劇團(Kneehigh)也在這個時期開始發展其獨特的、富有趣味的無政府主義式小醜表演,並以《瑟堡的雨傘(The Umbrellas of Cherbourg)》及《相見恨晚(Brief Encounter)》等劇目而廣受觀眾歡迎。

在1990年代,包括火山劇團(Volcano)及瘋狂大會劇團(Frantic Assembly)在內的眾多新興實驗團體融合了肢體劇場、編舞以及文本,發展出了一種獨特的風格。包括DV8在內的團體也致力於發展舞蹈與劇場藝術的跨界融合。DV8的創作也與傳奇編舞家皮娜·鮑什(Pina Bausch)的作品相似。

Meanwhile influenced by the work of Philippe Gaulier and Jacques Lecoq, companies such as Theatre de Complicite applied their style to the reworking of classic texts and created new work in collaboration with writers.

In the 1980s and 1990s companies like Forced Entertainment sought to create a theatre reflecting the collision of styles and bombardment of imagery that pervaded the late 20th century. ‘Some Confusions in the Law’ and ‘About Love’ gave expression to a bleak post-Thatcher landscape. On the other end of the spectrum Cornish theatre company Kneehigh began to develop and hone their playful style of anarchic clowning that would go on to enchanting audiences in shows like The Umbrellas of Cherbourg and Brief Encounter.

In the 1990s young experimental companies such as Volcano and Frantic Assembly developed a unique style, fusing physical theatre, choreography and text. The cross-over between dance and theatre was also explored by dance companies such as DV8 whose work bears resemblance to that of choreographer Pina Bausch.

英國劇場藝術傳統的文本特性舉世聞名。自莎士比亞至約翰·奧斯本(John Osborne),再到“直面戲劇”一代的眾編劇——劇本創作者有著最高的權力。但在過去的四十年內,英國見證了一個企圖推翻文本暴政的革命。

從1970年代開始,英國戲劇團體開始實驗一種更加偏重肢體表現的戲劇形式。他們希望逃脫現實主義或自然主義戲劇的控制,融合舞臺設計,編舞以及肢體圖像等元素創造一種充滿力量的視覺風格。

一些戲劇團體及藝術家開始從純藝術中尋求靈感。躊躇與展現劇團(Hesitate and Demonstrate)的杰拉爾丁·皮爾格蘭(Geraldine Pilgrim)與珍妮特·戈達德(Janet Goddard)堅持創造這樣一種藝術作品:這作品不能通過畫廊等商業機構售賣,強調現場性、當下的時刻以及非物質性。兩位藝術家探索了高度視覺化表演風格和美學;她們創作的作品中的主角總是女性。

Companies also began to combine other visual media into their theatrical practice. Today Forkbeard Fantasy explores the comic dynamic between film and live performance, allowing actors to merge, apparently seamlessly, from real life into film, while Complicite’s work has become much more multi-media based as artists try to represent our increasingly digital world.

Looking back over the 20th century these developments are not completely new – in the 1960s Peter Brook had become interested in a more physical and visual theatre. He had been inspired by Japanese Noh theatre and influenced by the work of Adrienne Mnouchkine’s Theatre du Soleil in Paris. In London improvisational fringe theatre company People Show were experimenting with visually structured shows, establishing a risker and more dangerous relationship with the audience based on impulse and direct imagery.

While even earlier international innovators in this area included Bauhaus, Dadaist and surrealist performers, choreographer Rudolf Laban and directors Meyerhold and Jerzy Grotowski and Richard Schechozer.

While even earlier international innovators in this area included Bauhaus, Dadaist and surrealist performers, choreographer Rudolf Laban and directors Meyerhold and Jerzy Grotowski and Richard Schechozer.

各個劇團也開始了在劇場實踐中使用其他視覺媒介。弗可比爾德幻想劇團(Forkbeard Fantasy)探索了電影藝術與現場表演之間的趣味能量,並為演員在現實與電影之間的流暢穿越提供了可能。另一方面,出於真實反映我們日漸虛擬的世界的願望,同夥劇團的創作則越來越多地依賴多媒體進行表演。

回顧20世紀,以上提及的實踐發展並不是前所未聞的——早在1960年代彼得·布魯克(Peter Brook)就對一種更加重視肢體表演以及視覺性的劇場藝術充滿興趣。他深受日本能劇以及阿德里安娜·莫努希金(Adrienne Mnouchkine)於巴黎創立的劇院馬戲團(Theatre du Soleil)影響。在倫敦,即興小劇場劇團人民公演劇團(People Show)積極地進行有著強烈視覺結構的表演,通過沖動行為和直接的圖像建立了一種更加危險的劇場體驗關系。

國際範圍內,視覺劇場藝術實踐的先驅包括包豪斯、達達主義者、超現實主義表演者,編舞家魯道夫·拉班(Rudolf Laban)、導演梅耶荷德(Mayerhold)、耶日·格洛托夫斯基(Jerzy Grotowski)以及理查德·謝喜納(Richard Schechozer)等。

A cohesive relationship between traditional and visual theatre seemed at one point to be impossible, with this work originally perceived with great suspicion. “The battle in the 1980s and 1990s came in the constant form of conversations that began ‘is this really theatre?’ and ‘is this really acting?’,” Etchells explains. In order to make space for the visual, the idea that text had to be destroyed in its entirety was prevalent.

Interestingly there is still a space for this sort of narrative free work, with companies such as Punchdrunk creating immersive performances that utterly eschew any idea of story.

However for other companies the relationship is much more holistic; text may still be the starting point for many British theatre makers but there is now an implicit understanding that making theatre involves many other aesthetical considerations too. The playing floor is wide open now to include imagery, movement, sound, music, mime, dance and art, as well as words.

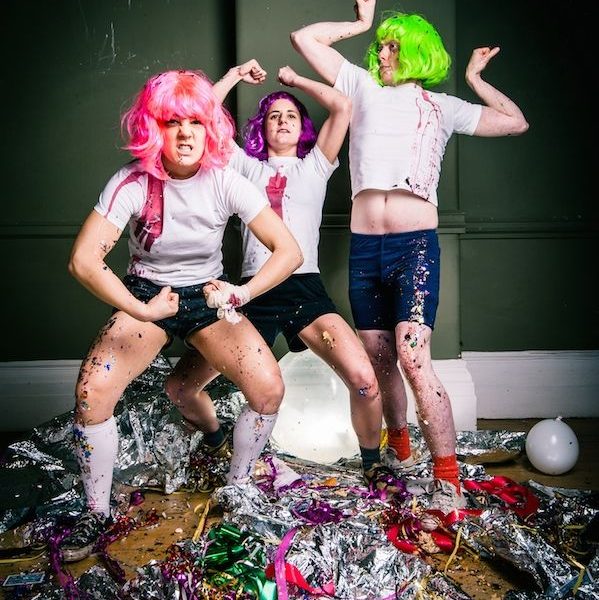

One of the most exciting new companies working in London at the moment, Made In China, is run by playwright Tim Cowbury and performance artist Jessica Latowicki, who create work that fuses together myriad theatrical techniques to try to find meaning in a multi-faceted world. Meanwhile companies such as 1927 are delighting audiences with their  unique brand of gothic animation, while the London Mime Festival continues to push the boundaries of what visually based theatre can be.

unique brand of gothic animation, while the London Mime Festival continues to push the boundaries of what visually based theatre can be.

傳統劇場藝術與視覺劇場的融洽關系似乎是不可能的,因為在最初產生的時候,視覺劇場就飽受質疑。艾秋斯(Etchells)指出:“1980以及90年代劇場藝術之間的鬥爭往往開始於這樣的問題:‘這真的是劇場藝術嗎?’及‘這真的是表演嗎?’”為了留出空間給視覺性以發展自身,“文本必須死”曾被視作是視覺劇場的第一要務。

有趣的是,現在仍有戲劇團體致力於創作完全不含敘事性的作品。暈眩劇團(Punchdrunk)的浸入式戲劇表演完全避免了有關敘事的任何概念。然而,對於其他戲劇團體來說,眾元素之間的關系是密不可分的:對於部分英國戲劇從業者來說,文本可能仍然是每一次創作的起始點,但人們已經認識到,其他美學考慮對於戲劇創作來說同樣重要。當下的劇場包羅萬象——圖像、肢體運動、聲音藝術、音樂、默劇、舞蹈、藝術以及文字等都在戲劇舞臺上有著一席之地。

在倫敦,近年來最有趣的戲劇團體包括由編劇蒂姆·寇布瑞(Tim Cowbury)以及表演藝術家傑西卡·拉托維奇(Jessica Latowikci)共同建立的中國製造劇團(Made in China)。他們的作品融合了多種戲劇手法,嘗試在一個多元世界尋找意義。1927等團體通過獨特的哥特式動畫受到了觀眾的歡迎,而倫敦默劇節則持續地擴展著視覺劇場的意義。

For Etchells the main outcome of the visual theatre revolution was the freedom to avoid categorisation in a British theatre ecology slavishly beholden to labels. He is now interested in working within a space that subverts language from within its own constructs. “In order to challenge language and ways of thinking about language [Forced Entertainment] began to move into working with language itself,” he explains. “Our challenge to the primacy of language means we are now trying to challenge language on it’s own terms.”

He thinks that these developments arose through the battles of the late 20th century. “In Britain I still feel the power of the playwright is utmost, but the general sense of what theatre might be has expanded considerably. That’s to do with these ideas bleeding into the mainstream, and with ourselves and other artist getting recognition for what we do. Things have come along in a good way. Back then ground was gained and doors were opened and to a certain extent they’ve been held open.”

As we go into 2015 the terrain of British theatre is a much more vivid landscape than it used to be. It is now expected that a show will have a certain visual element to it – whether that be through the design, multi-media or movement work. This expectation has moved into much of the new writing being produced now, with play texts reflecting these new aspects, either in heavily descriptive design stage directions or, alternatively, through a complete absence of them, leaving the floor wide open for the most visual imaginations to fly.

Looking back over this rich history of visual theatre Etchells believes that “the questions that drive all these shows are similar. They’re about ‘what is meaning?’, ‘what is narrative?’, ‘what is language?’, ‘how can we explain and describe the space we’re living in, the culture that we’re living in with all the means at our disposal?’, with whatever we can grab hold of,” he stops and grins. “People don’t live in a particular genre anymore.” The world, both texturally and visually is quite literally our oyster – how exciting to imagine what in the next 40 years that oyster will look like.

對於艾秋斯來說,視覺劇場革命的主要成果是不被他人分類及定義的自由——英國劇場生態總體傾向於為作品及團體貼上各種標簽。艾秋斯希望在一個以其內部構成顛覆語言系統的空間內進行創作。“為了挑戰語言以及關於語言的思考方式,我們開始在語言之中進行創作,”他解釋道。“我們對於語言首要性的挑戰意味著我們現在要以語言本身來挑戰語言。”

他認為這些發展是通過20世紀晚期的鬥爭發展開來的。“在英國,我仍然能夠感覺到編劇至高無上的權力,然而有關劇場的一般理念已經得到了很大的發展。這是因為挑戰性的理念成功進入了主流戲劇世界,我們以及其他類似的藝術家得到了認可。狀況已經越來越好。我們爭取到了領地,打開了牢籠。”

我們已經進入了新的時期,英國劇場藝術的圖景已比過去更加多姿多彩。觀眾對於一場劇場演出的期待已經包括了對於視覺元素的期待——這視覺元素可以是設計、多媒體或是肢體運動。這種期待進而被轉入了當下的新寫作之中,戲劇文本之中已經對這些改變做出了反應。文本中或包括了大量的關於舞臺設計的指導,或完全沒有這些——通過把權力完全轉交給其他藝術家,讓視覺想像力自由地飛翔。

回顧這段豐富的歷史,艾秋斯相信“推動這些表演的問題是類似的:‘什麽是意義?’‘什麽是敘事?’‘什麽是語言?’‘我們如何能夠通過各種方式解釋並描述我們生活於其中的空間,我們生活於其中的文化?’”“以任何我們能夠使用的方式。”他停下來,笑了笑。“人們不再生活在一個特定的藝術門類之中。”如英國諺語常說的一般,文字的或視覺的世界都是我們的牡蠣——想像這個牡蠣在接下來的40年內的變化,真是一件讓人興奮的事情。