TEXT 撰文 x BY GONG ZHIYUN 龚之允

Fig. 1 The site of Yinchuan MoCA

Museums in China have problematic identities, and their museological practice can be experienced differently than those institutions in the West. The Yinchuan Museum of Contemporary Art (Yinchuan MoCA, Fig. 1), which opened in 2015, is an example of the controversial identity of museums in China. Its planning and necessity in contemporary Chinese society have been discussed since the initial proposal of its development.

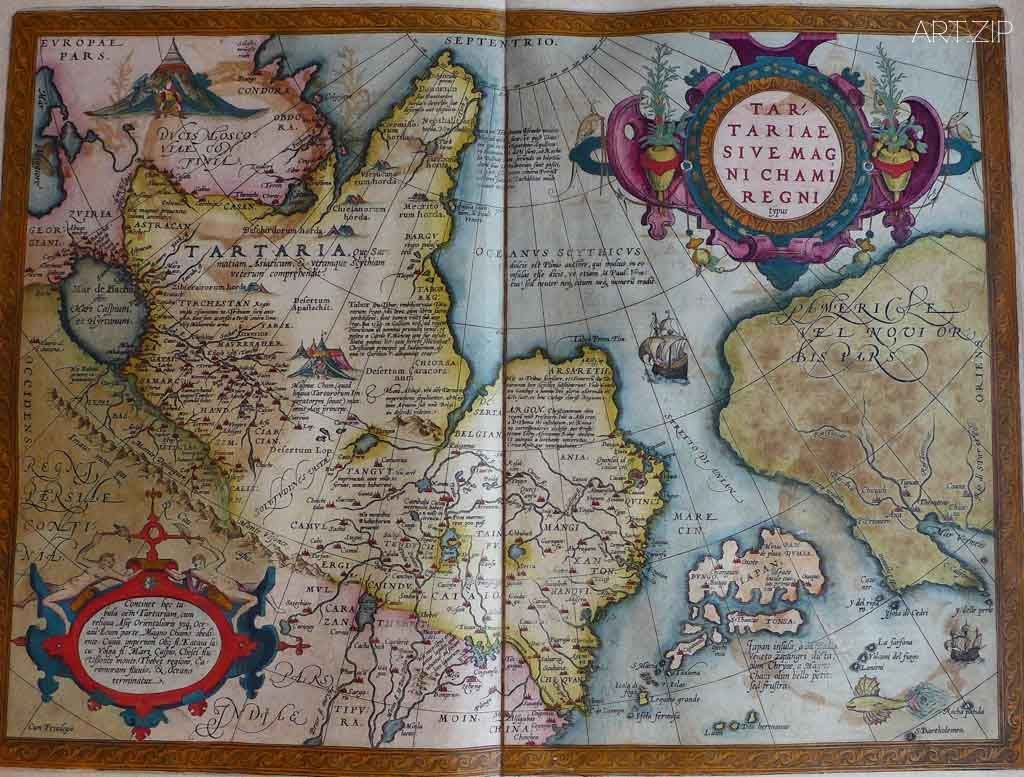

The whole project of founding the museum cost nearly 300 million USD.[1] Meanwhile, Yinchuan, the capital of Ningxia province, is an inland, less populated and relatively poor city. Why Yinchuan? The locality of the museum is questionable. Ironically, its permanent collections of Western-influenced Qing dynasty paintings and antique maps since the Renaissance, contradict the museum’s contemporary identity. Why is it important to have these two collections that are so remotely connected with contemporary art?

In 2014, before the museum’s opening exhibition, an international conference “The Dimension of Civilization” was held, discussing the identity of China since the Renaissance in the context of globalisation. To what extent would the conference help establish its academic authenticity to the public? Would such an authentication be necessary in the context of New Museology?

This article will address the above-listed issues and discuss: firstly, the operational cultural strategy by explaining the nature of its funding; secondly the curatorial selection of its two seemingly irrelevant permanent collections; thirdly its historical and contemporary position in museology and art history.

Private Museums in China: Game of profits?

China plays a significant role in building new museums, especially the private ones, in the twentieth century. According to Private Art Museum Report, Larry’s List[2] – first thorough survey of the subject matter – there were 317 private museums of contemporary art, among which 26 were in China, placing the nation the fourth fast growing entity in the world. Opening private museums is a relatively contemporary phenomenon, actually half were established after 2000.[3]

Museum maintenance has been problematic and a pressing issue, whether the funding schemes are public or private. Since 2007, Western museums suffered tremendously from funding cut, due to the still ongoing global economic recession, which was initiated in the United States.[4] Meanwhile, this global financial crisis did not affect China immediately, which gives the country at least three year buffer period, as the central government of China introduced a series of grand planned investment in infrastructure. This policy had a great impact on the growing real estate market- the financial baseline for contemporary Chinese art in the domestic market, but also indirectly by strong contrast against the stagnant Western economy; foreign capitalists flowed into China for the nation’s prosperous economic growth expectation. Many businesses, including a great deal of overseas hedge funds, invested into contemporary Chinese art,[5] and accordingly collections were built and subsequently required space to store and exhibit.

Yinchuan MoCA was initiated in 2012 by Minsheng Real Estate, as part of urban development plan called “The Golden Shore of the Yellow River – Chinese River Map” (黃河金岸•華夏河圖), which is now a new downtown in developing.[6]

This is not the first time this Minsheng supported contemporary art. Established in 1998, the company started working with one of the most influential art critics and contemporary historians Lu Peng (呂澎) as early as in 2004. They did an architecture project called “Hope Land” (賀蘭山房) and invited 12 well-known contemporary Chinese artists to design their own style building projects.[7] However, the invited artists were primarily painters, less experienced in architectural practice, six months after the initiation of the project, all individual plots confronted various issues. Consequently, the whole project was incomplete and was thought to be a trans-art-fields failure.[8] Due to the controversy of this project, the chairman of the board of Minsheng Real Estate stepped down, and the former member of the board, Ms Liu Wenjin (劉文錦), who interfered and helped the project with more pragmatic financial and juridical consultation, was elected to run the company.

In 2012, with Lu Peng as the deputy director, Minsheng started working with the provincial government to initiate building Yinchuan MoCA. Making a museum is not as the same as building housing plots because it requires not only a huge amount of money for maintenance but also those permanent collections are supposed to be acquired before the opening, let alone the strategic plan in outlining how to attract potential visitors and subsequently the membership schemes.

Since the press release with regard to building Yinchuan MoCA, the necessity and feasibility of having an art museum in Yinchuan has been widely discussed in the Chinese art circle. For example, art critic Fei Dawei (費大為) argued that building an art museum with such a massive funding in a relatively poor area in West China was astonishing and believed the initial funding, as tremendous as it may appear, was less significant than the long-term annual operating cost that would ensure the academic influence and social dynamism of the museum. He further asserted that without the influence in the field of research, the museum would be a waste.[9] According to him, if the annual operating fee could be guaranteed to be above 5000 China Yuan per square metre, with a professional curatorial team, it would be sufficient in making decent exhibitions.[10]

Some art critics felt it was a trick and a dubious game, in the name of art, the intention behind the scene was for the real estate company to obtain the license of developing the area with much lower price. Cheng Meixin (程美信) stated that there were only 2 million citizens in Yinchuan, and its annual GDP per citizen was far less than those of the cities such as Beijing and Shanghai (approximately 85% less), which means in order to operate this museum properly, selling tickets and accessories would not be its major source of income, and the maintenance demand from Minsheng would be too enormous to afford.[11] In a sense, Yinchuan MoCA was suspected to be a fraud or a temporary means for gaining the license fee reduction; and after the land was granted, the museum is likely to be abandoned or the company would stop providing sufficient funds for maintaining.

Lu Peng, as the museum project’s initiator and opening exhibition curator, when being asked if this was part of an enclosure movement for the new capitalist in China, he responded that it was too early to discuss such a matter orally, because the following curatorial practice in the museum for art ecology would serve a proper answer.[12]

As for addressing the issue with regard to the professionalism of curating exhibitions, Lu Peng admitted that in China there was no professional museological team to support contemporary art institutions in China. However, the board was well aware of this matter and started to establish an international board for a wider curatorial scope. It was reported that Wilfred Cass (The Cass Sculpture Foundation, UK), Akira Tatehata (the chancellor of Kyoto University), Yu Deyao (余德耀 the director of Yuz Museum, Shanghai) and Sui Jianguo (隋建國 Sculptor at the China Central Academy of Fine Arts) had joined the board. In addition, enormous funds for acquiring permanent collections were pledged, therefore the museum was not going to be a gallery space for rental, but a proper public space.[13]

In recently years, opening private museums, especially those dedicated to contemporary art, has not only become a social phenomenon in China, but also a symbolic gesture showing power for the new Chinese economic anchor – private capitalists – to show their wealth and taste. For example, The Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art officially opened on 5th November 2007; the Long Museum was funded and opened in 2012 by Liu Yiqian and his wife Wang Wei (劉益謙、王薇), and the couple also invited Lu Peng to be a member of its academic research board;[14] Yu Deyao, a member of the board of Yinchuan MoCA, opened his own Yuz Museum in Shanghai in 2014.

It was not a coincidence that more blockbuster private museums such as MoCA Yinchuan were built after 2007, because the Chinese government made new policy in encouraging private economics. On 8th March 2007, at the 2nd Plenary Session of the 10th National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, the Vice Chairman of the Standing Committee Wang Zhaoguo (王兆國) made interpretation and acknowledged the legitimisation of private properties. Thereafter, private capitalists can finally be under legal protection, and the communist government will encourage the development of private economics in Mainland China.[15]

It could be said that due to the rise of Chinese capitalists as a social class, the private museum growth in China can be seen as an extension of global capitalist cultural promotion. The origin of private collections in China and the West shared similarities, both started by the aristocracies, while museums as a public space did only come into being with the rise of the capitalists, as early examples can be found in Britain.[16] However in China, the communist regime made Chinese art museums governmentally operated, and only until the open policy was introduced and reinforced in 1993, had private funding started to invest and sponsor art and museums. An early example of art event sponsored and invested by private entrepreneurs in China was the Guangzhou Biennale 1992 that was curated by Lu Peng.[17] Private museums, such as MoCA Yinchuan, can be seen primarily as an intellectual investment – a dynamic communicative result of a series of negotiations among the government, curators and collectors.

Furthermore, the architecture of the site received various nominations for global awards. It can be said, this was the most obvious and immediate response and glory that the investor Minsheng anticipated. The design and construction of MoCA Yinchuan in 2015 was nominated for Woman Architect of the Year for Emerging Architecture[18]; in 2016 was enlisted in the finalist World Architecture Festival.[19]

So far as the building of the museum is concerned, it can be self-evidently regarded as a work of art, however establishing a space for a museum is just a part of museum making process, there are various concerns with regard to further development.

Lu Peng pointed out that due to the self-interests of the funding parties – i.e. the government wished to gain political achievement (without directly providing funds), and the private companies wanted to promote its corporate image – in actuality, very often, the maintenance fee for operating a museum would suffer a cut in funding.[20] According to him, a professional museum needs to be evaluated by four functions: exhibitions, collections, academic research and public education.[21] Because collections especially the permanent ones are the nexus of the four aspects, their value and nature are crucial to a museum, meanwhile in the case of MoCA Yinchuan, there appears a conflict.

Far fetched permanent collections:

MoCA Yinchuan defined itself as a museum of contemporary art, and it would make much more sense that its permanent collections are related to contemporary art, however as a result, ancient maps and early Chinese oil paintings were selected by the chief curator Lu Peng as appropriate choices. It only arouses questions with regard to MoCA Yinchuan’s cultural positioning.

Yinchuan is the capital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, and had cultural significance on Silk Road. Due to the geography of Hetao of the Yellow River (河套), relatively it has a much better environment than other cities in West China. The majority of its citizens are Muslims other than Han Chinese, and the city is a representation of cultural diversity.

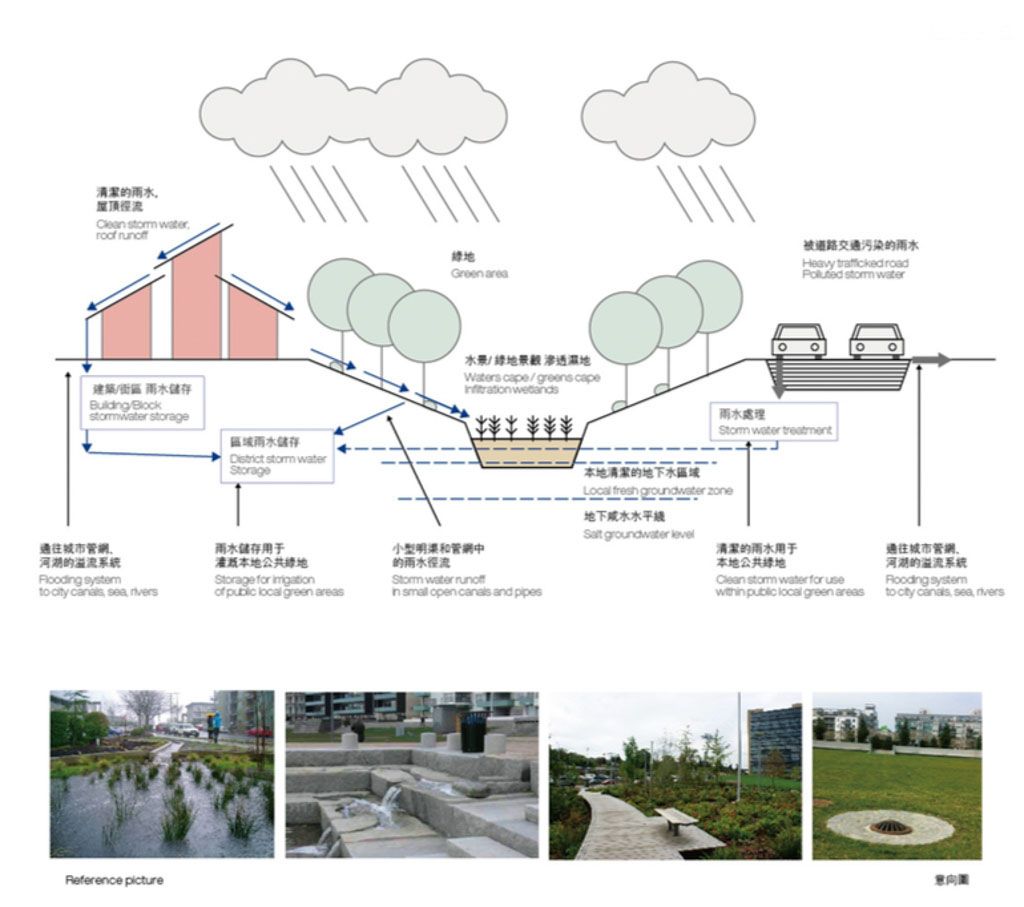

Fig. 2 The ecology of The Golden Shore of the Yellow River – Chinese River Map

The museum was designed to accommodate this local feature, for example it was surrounded by organic rice fields (Fig. 2), and its main colour is white with a green logo, both of which have Islamic religious implications; meanwhile the two permanent collections appear to be less relevant to neither the history nor the culture of the city.

Two academic monographs accompanied the two permanent collections respectively, while for early Chinese oil paintings there was a separate and dedicated catalogue. The two monographs served as cues for reinforcing the academic significance of the collections in art history.

The ancient maps collection mainly explore the cultural communication between late Ming dynasty China and Post-Renaissance Europe in the 17th century. Maps could be regarded as objects of visual culture that reflect the change of the relationships between Chinese and Western societies. The Jesuit missionaries made a tremendous contribution in such a cultural exchange, however their influence was less obviously extended in Ningxia.

The curator and author of the ancient maps collection is Prof. Guo Liang (郭亮 Fig. 3), the deputy head of Shanghai University, a visiting scholar at Princeton. He is the leading expert in Renaissance history of science and maps, and he was invited by Yinchuan MoCA to select maps in Europe and make the collection. His curatorial intention is well expressed in the introduction of the exhibition:

The Jesuit missionaries came to China in the late 16th century, and they made a great impact on modern Chinese history. The cultural exchange of cartography between China and the West influenced the art of map making in China. Cartography is not only about science but also involves artistic creativity. This exhibition aimed at presenting ancient maps produced in Europe from the 16th to the 19th century, through which hopefully an understanding can be established: maps are objects of art, a unique expression associated with but not limited by drawing and print making…Through the pathways of Chinese and Western exchange found in the old maps of the collection of MOCA Yinchuan, this exhibition will outline a shifting geographic context of internationalisation. Meanwhile, research into the art of ancient mapmaking will illuminate the exchanges, learning, imitation and improvements on Eastern and Western mapmaking, as well as the underlying social and cultural changes.[22]

The collection of ancient maps as well as the exhibition challenged the traditional view of art history. Guo Liang, by presenting his research, showed the boundary of art history could extend to a broader and interdisciplinary cultural stance. In viewing the Jesuits activities in China, it becomes clear that art is part of cultural and social exchange; and the map exhibition not only has a wider public educational purpose, but also can provide new perspectives in academia. It is unthinkable that without maps and great exploration, humanist ideas could spread widely all across the world.

The highlight of this collection is Tartariae Sive Magni Chami Regni typus (Fig. 4). This colour print etching was made by the first world atlas maker Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) and is one of the only forty surviving copies. The map illustrates the European knowledge about China at that time, particularly at the detailed depiction on the “kingdoms of Tartar and Japan”.

At the opening of the exhibition, Guo Liang stressed the political importance of maps to the audience by relating the collection to the diplomatic gift from the Chancellor of Germany, Angela Merkel to the Chairman of China, Xi Jinping – a German made Chinese map dated 1735.[23] It reinforced the curatorial intention with regard to museology that the “permanency” of Yinchuan MoCA relied on the beyond-art interdisciplinary representation of its collection in history and culture.

Fig. 5 Giuseppe Castiglione, The Portrait of Emperor Qianlong, c.1756-1757, oil on paper, 62 x 49.5 cm, Yinchuan MoCA

The early Chinese oil paintings collection appeared to be less of a “digression” of art, and could be considered as the primary collection, as has indicated by its proportion in the publishing scheme. The highlight of this collection, The Portrait of Emperor Qianlong (Fig. 5) could further exemplify how history of art can be challenged by promoting the established concept of alternative approach.

Many art historians in the field of East Transition of Western Painting (西畫東漸) have identified The Portrait of Emperor Qianlong had a great historical, political and cultural significance in early communication between China and the West on a higher level.[24] By having this object, Yinchuan MoCA is able to convey its academic authenticity, with regard to the originality of the Chinese related global art history. The painting is regarded as a collaborative work between the Emperor Qianlong (the patron) and the Milanese Jesuit artist Giuseppe Castiglione.[25] According to recent studies, it unfolds a much more accurate circumstance than previous assumption with regard to Qianlong’s attitude towards Western art. By overturning the established historiography, this portrait served as an evidence that sheds new light on the field. Therefore, by collecting and exhibiting such an object of art (and artefact), the museum, arguably, to some extent could have the power to reinterpret history, therefore possess art historical authenticity and significance. In competing with similar institutions dedicated to contemporary art, Yinchuan MoCA, controversially, could prevent itself from the “scandalous” marketing scheme of contemporary art. Because with such an object as well as this collection, the museum is able to align itself with prestigious governmental museums such as the Palace Museum, Beijing. It could be suspected, historical authenticity and value were the chief curator Lu Peng’s strategy in addressing his rivals’ conspiracy theories (for example Fei Dawei).

As for the collector, Liu Wenjing, the owner of the museum, The Portrait of Emperor Qianlong could serve as a medium for her to gain the privilege that cannot be quantified by price. This kind of portrait is categorised as “imperial visage” (御容), exclusively for the Chinese emperors. By having this piece, the collector is able to align herself in history with the highest ruler in China, and such a pleasure can be said as the representative of the non-materialistic profits that a private museum function for its owner — achieving a sense of eternity.

Moreover, this painting exemplifies a unique feature of the order of things in China, as Michel Foucault once pointed out:

…a ‘certain Chinese encyclopaedia’ in which it is written that ‘animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification…In the wonderment of this taxonomy, the thing we apprehend in one great leap, the thing that, by means of the fable, is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own, the stark impossibility of thinking that…the Chinese encyclopaedia localises their powers of contagion; it distinguishes carefully between the very real animals … and those that reside solely in the realm of imagination.[26]

The Chinese order distinguishes from the Western model by having a particular ideological hierarchy of art. The highest class is categorised as belonging to the Emperor, and such a notion can be found in Chinese art historiography; for instance the Xuanhe catalogue of paintings (《宣和畫譜》) , Sanxitangfatie (《三希堂法帖》) and Shiqubaoji (《石渠寶笈》) collected masterpieces of ancient Chinese fine art, and they were compiled due to the private interests of the emperors. The Portrait of Emperor Qianlong was a newly discovered piece of oversea provenance, and the recent studies of the imperial archive at the Palace Museum, as well as the letters by the French Jesuit painter Jean-Denis Attiret, now in the Jesuit headquarter Rome, could represent the circumstance in which the painting was made. As it turned out, Qianlong required artists to be faithful in portraying his imperial visage; artists were permitted to stay as close as half a meter away from the Emperor in painting his portraits; the Emperor even specifically asked them not to neglect the imperfection of his left eyebrow; all are well represented in The Portrait of Emperor Qianlong and challenged the traditional impression that Qianlong was ostentatious therefore his portraits were beatified by the employed artists.[27] This new discovery was sponsored by Yinchuan MoCA, and demonstrated its academic depth in competing with the Palace Museum.

Furthermore, before entering into a museum, an object of art held its exchange value, namely it could be estimated by a price; and in the case of The Portrait of Emperor Qianlong due to its imperial provenance, once in the possession of Yinchuan MoCA, the exchange value ceased for being a permanence collection of a public space, nevertheless it still holds a symbolic and political value that is deeply associated with the previous life of a museum object. Susan Pearce proposed that the role of collections is active and changeable depending on different social situations:

Collecting and collections are part of our dynamic relationship with the material world. Object grouping, like all other social constructs, is born from the essential mysterious workings of the communal and individual imagination, sanctified by social custom but capable of growth and change. But for an object group to count as a ‘collection’, whichever of a range of words may appear suitable for this activity and its outcome through time, it must have been created as a special accumulation, intended at some point in time to fulfil a particular social and psychic role, and considered by the collector’s society to be appropriate for this role, a view which, however, the collections themselves will actively influence.[28]

The Portrait of Emperor Qianlong has the function of leading the early Chinese oil painting collection in demonstrating MoCA Yinchuan’s impact in reconstructing the communicating history of art between China and the West from its incipient period (early globalisation of art). The collection may appear have less direct connection with the field of contemporary Chinese art, nevertheless in the age of Post-Colonialism, contemporary Chinese art, generated in the process of globalism, can be re-contextualised once again, because of the reinterpretation of the early globalisation of art. Therefore, its curator Lu Peng’s academic intention became legible: giving the museum a sense of authenticity from the angle art history.

A well-informed context is of vital importance for Lu Peng, because he believed that in order to evaluate art and maintain the ecology of art, one must be given a context, which served as a map for navigating the cultural significance of an object or a collection. He would even go so far as to declare: “all cultures are strategic…art historians must embrace the commercialisation of art, and operate and write art history [操作藝術史] by actual curatorial and marketing practices”.[29] The permanent collections in Yinchuan MoCA reflected his art history operational idea; by reinserting, repositioning and reinterpreting the early global history of art, the ideology of the museum can be operated at the level of a grand cultural sphere.

In 2014, one year before the official opening of the museum, Yinchuan MoCA held an international conference “The Dimension of Civilization”, that specifically addressed various issues with regard to the relationship between Globalisation and China. It was an interdisciplinary conference. Researchers from different fields, such as Chinoiserie, 18th-century history of science, Chinese export art, exchanged their new findings, and waved a tapestry of a globalisation of art from the 17th century onward. This conference set the tone of the museum’s curatorial strategy: exhibiting art with a macro scope of culture.

The contemporaneity of Yinchuan MoCA:

Despite the controversial position of Yinchuan MoCA in the urban real estate planning, a new type of museology can be experimented in so far as the gentrification of the area is concerned. Critics like Fei Dawei made a valid point in asserting that with the humanistic environment in Yinchuan, a grand museum seemed to be a waste of resources. In fact, “The Golden Shore of the Yellow River – Chinese River Map” is located at the outskirt of the central Yinchuan, which means the museum could hardly rely on the local viewership. Viewership is crucial in museology and its practice, it is well nigh unthinkable that without the support of the local communities, the museum as a publicly and culturally interactive space could function properly.

There are a few factors, in the case of Yinchuan MoCA, may show new operating strategies that are distinctive from the conventional concept of a public museum.

First and foremost, in Sept 2013, the Chinese Chairman Xi Jinping proposed the national top strategy “One Belt One Road” (一帶一路), which aimed at building new economic environment alongside the Silk Road. Although in modern time, the silk road in the south via ocean played a more important role than the traditional north one via land, “One Belt One Road” was initiated with the Chinese infrastructure industry in Middle Asia. Yinchuan, as a city connecting Han Chinese and Muslim cultures, tended to be a significant centre for economic and cultural exchange in “One Belt One Road”. With the support of governmental policy, the economy in Yinchuan has grown rapidly. For example in 2014, its export good trade reached 4.5 billion USD, and the annual growth is 86.7%.[30] The sponsor of Yinchuan MoCA, Minsheng Real Estate as the “landlord” of the new Yinchuan, in this case was able to gain more profits from “One Belt One Road”, as the new Yinchuan, that Minsheng contributed in developing, is transcending its cultural and economic status. Instead of considering how to accommodate and serve the existing local community, Yinchuan MoCA employed a turnabout strategy: establishing its local community in the process of making the museum.

Secondly, contemporary art curator Xie Suzhen (謝素貞) is employed as the art director (藝術總監) of the museum and her schemes filled the gap between the two ancient art collections and the contemporaneity of the museum positioning. In summer 2016, Yinchuan MoCA staged its recent purchased contemporary Chinese art collection as an exhibition called “Flourishing Leaves” (“其葉蓁蓁”), and the leading works of art (Fig. 6) were made by a few well-known living artists, such as He Duoling (何多苓), Mao Xuhui (毛旭輝), Ye Yongqing (葉永青 ) and Yue Minjun (岳敏君). The four artists were frequently discussed in various publications on contemporary Chinese art. Both Lu Peng and Fei Dawei acknowledged the contribution of the four in their publications. By collecting and exhibiting their work, Yinchuan MoCA can be regarded as a proper museum of contemporary art in China. It once again elucidated the curatorial scheme of the museum: authenticate its contemporaneity based on historiography. Similar strategies can be seen in some private museums directed by Lu Peng previously, such as MoCA Chengdu and Group Museums of contemporary Chinese art, Qingchengshan (青城山中國當代美術館群).

Thirdly, in autumn 2016, the museum invited Indian curator Bose Krishnamachari to curate Yinchuan Biennale, and Yinchuan MoCA’s international influence in return is expected to be increased. The participating artists included Anish Kapoor, Yoko Ono, Liam Gillick, Mary Ellen Carroll, Cao Fei, Song Dong and so forth. Such a list can even make Beijing and Shanghai jealous. Some artists were invited to reside in the artists’ villa, an extended area nearby the museum. With the artists’ influence, Yinchuan MoCA wished to establish an ecologic art platform in a long run. Biennales in the West are regarded as art fairs, while in China they distinct only a little from exhibitions. Such a model is a norm in practice in China, for example, Guangzhou Triennial (previously a biennale) is hosted by Guangdong Museum of Art and Shanghai Biennale is hosted by Power Station of Art, however, the two hosts are owned by the communist government, while Yinchuan MoCA is privately owned. In hosting a biennale, Yinchuan MoCA not only promoted itself on an international scale, but also demonstrated its ambition in aligning itself with the governmental museums.

Lu Peng’s emphasis on unique context in historicising art history can be modified and applied in the museology in China. Although the Chinese government now acknowledges the right of private ownership, the communist ideology still exists in the nation’s museology: governmental museums have more prestigious recourses (policy and funds) in collecting and exhibiting art. As this article has mentioned before, establishing private museums in China is still a new phenomenon. There are various problems in fundraising, tax reduction and political censorship, how to make private museums of art function properly is still in experimenting.[31] The Yinchuan biennale was also involved in a political scandal: due to the censorship, Xie Suzhen had to cross off the name of Ai Weiwei on the invitation list,[32] and after this incident, Anish Kapoor was said to consider withdrawing the biennale for supporting Ai Weiwei.[33] As a result, Anish Kapoor remained in the Biennale, and controversially, Yinchuan MoCA gained wider attention both domestically and internationally, due to the fame of Ai Weiwei. In this case, Yinchuan MoCA is in the front line of making its own contemporaneity by engaging with contemporary art incidents.

Conclusion:

To conclude, Yinchuan MoCA is a unique and fine example in illustrating the current situation of private museums in China. Its initiation is deeply involved with the flourishing real estate industry as well as the rise of the new capitalists in China. The seemingly digressed permanent collections of ancient art demonstrated its academic ambition in art historiography and in competing with those governmentally owned national museums. The museological strategy is to define itself as a cultural intersect that could push temporal and geographic limits of its site.

The opening exhibitions and conference made the scheme of the museum clear: re-contextualise art in globalism. And the subsequent exhibitions of contemporary art, including the Yinchuan Biennale can be seen as the extension of making global art phenomenon. Because of the unique social milieu in China, private museums operate in a relatively “alien way” than those in the developed countries, nevertheless its idiosyncratic practice showed new approaches in museology.

Despite that so far blockbuster private museums of art such as Yinchuan MoCA, The Long Museum and Yuz Museum are operated well, it must be acknowledged that museums in China have more problems and are less professional than those in the developed countries, with regard to censorship, tax reduction policy, collecting and so forth.

Ref: