Part I

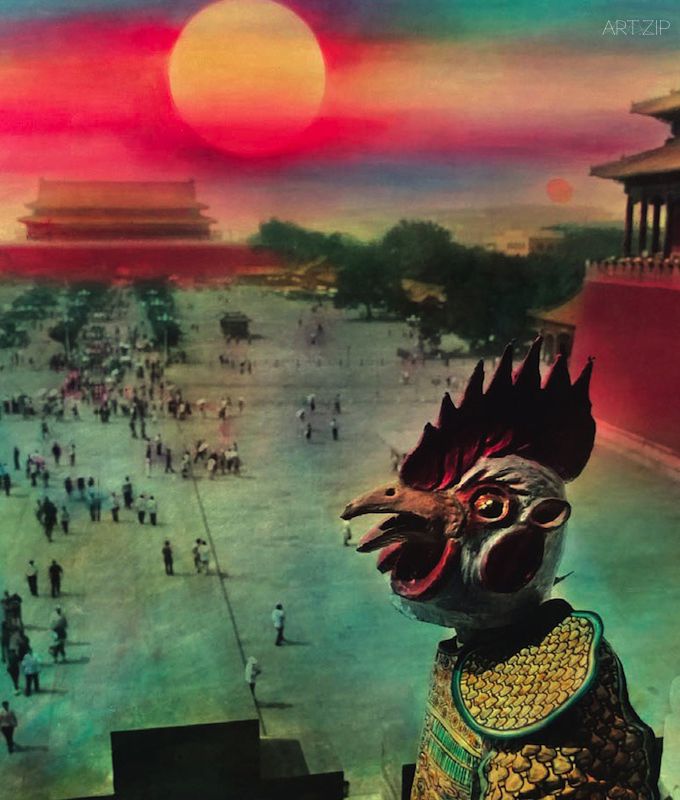

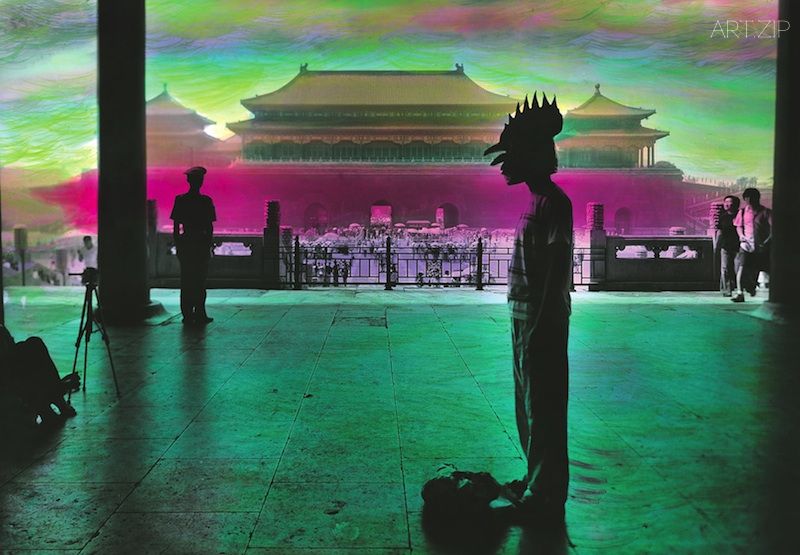

One “cock head man” who is wearing armor- somewhat like the Pleiades, one of the Twentyeight Mansions, only is short of royal crown which star monarch should have, while is added a blast of rustic taste from “grass stage troupe” – he arms akimbo, stands unexpectedly in the interchange between battlements and white marble railing on Meridian Gate. There are Tiananmen Gate Tower, a Square between Tiananmen and the Meridian Gate, and visitors sparsely on the Square, as well as a big round sun somewhat bleak in mist. All of them constitute “his” (or “its”) grand and rather fantasy background.

This piece of photo appears in some absurd, was taken by photographer Chen Nong in 2004~2005, and was included in his Forbidden City series. This work uses an overlooking perspective, there are two visual focuses on the quadrate picture: battlements, railings, which together with the standing akimbo “cock head man” into one large slice form a relatively independent foreground, focus on the “cock head” of the character – this is also the visual center of the view picture photo – but the perspective focus of the scene is the Tiananmen gate center at a distance, therefore, the Tiananmen appears to be nothing but a streak of virtual pale shadow in a thick mist, but all scenes (square, low houses, trees and the crowd on the square, side wings outstretched from the Meridian Gate, and the contiguous foreground in the form of a slice) on the ground are gathered to it. It can be seen a tense psychological relationship between the two focuses: on one hand, the “cock head man” is in the attractive force system with Tiananmen Square as the center, but “he” (or “it”) can not resist this; the other hand, “he” (or “it”) shows clearly an almost desperate protest will without yielding in the wide mouth, fiery anger crown, or scared or angry eye pupil, and trying to support posture.

There are thick mist, bleak sun, unexpected and absurd image, protest gesture of despair and passion in the attractive force system with Tiananmen Square as the center …… such a piece of work was created in “Political Pop” which is becoming a common vocabulary for sensitive period, also consists of a series of visual elements with sensitive social metaphor, is classified probably very easy in that category which belongs to the beginning of the political and symbolic social criticism art. However Chen Nong’s Forbidden City 06 is obviously not questioning for the social value system of ideologicalization – these are just used as an existing historical background – in fact that the work focuses on really the unexpected and absurd “cock head man”: who is “he” does “he” (or “it”) (or think) do in our society?

(一)

一個身穿甲胄的“雞頭人”——有些像二十八宿中的昴日雞,卻少了星君應 有的冠冕,多了一股“草台戲班”的土腥味兒——雙手叉腰,突兀地站在午 門上城垛與漢白玉欄桿的交匯處。天安門城樓,天安門與午門之間的廣 場,廣場上疏疏落落的遊人,以及一輪大大的、在霧靄中顯得有些慘淡的 圓日,構成“他”(或“它”)宏大而又頗為夢幻的背景。

這幅多少有些荒誕的照片,出自攝影家陳農2004年到2005年間拍攝的 《故宮》系列。作品採用俯視的視角,方形的畫面上有兩個視覺焦點:城 垛、欄杆和叉腰站立的“雞頭人”連成一片,形成相對獨立的前景,焦點集 中在人物的“雞頭”上——這也是整幅照片的視覺中心——但景物的透 視焦點卻在遠處天安門的城門中央,因此,儘管天安門看起來不過是濃 濃霧靄中的一道虛虛的淡影,但地面上所有的景物(廣場,廣場上低矮的 房 屋 、樹 木 、人 群 ,午 門 伸 出 的 側 翼 ,甚 至 是 連 成 一 片 的 前 景 )都 在 向 它 匯 聚。可以看出,在兩個焦點之間有一種緊張的心理關係:一方面,“雞頭人” 置身於以天安門為中心的引力系統之中,這是“他”(或“它”)無法抗拒的; 另一方面,在“他”(或“它”) 張大的喙、火焰般的怒冠、或驚或怒的眼瞳、 和竭力支撐的身姿中,分明流露出一種近乎絕望卻並不屈服抗爭意志。

濃重的霧靄,慘淡的太陽,以天安門為中心的引力系統,突兀、荒誕的形 象,絕望而又激情的抗爭姿態……這樣一幅創作於“政治波普”正成為一 個公共詞彙的敏感時期,又是由一系列有著敏感的社會隱喻的視覺元素 構成的作品,大概很容易被人劃入那類業已濫觴的政治化、符號化的社 會批判藝術的範疇。但陳農的《故宮06》顯然不是對意識形態化的社會 價值系統的追問——這些只是作為一種時代背景而存在——作品真正 的焦點是那個突兀、荒誕“雞頭人”:“他”(或“它”)是誰?在我們的社會 裡,“他”(或“它”)在(或想)幹什麼?

Part II

It is different from contemporary paintings which can be concocted arbitrarily a variety of non-realistic visual illusion, the photograph with sense of unique reality tells us, the cock head and armor of the “cock head man” are artificial props, “he” is not a monster, but is one man who hides his true face in a special “appearance of an actor”. Although it is impossible to determine the identity of the actor, but the absurd combination of this “appearance of an actor” and daily situation with obvious social metaphor not only suggests the spirit conflict between the character and the social environment, but also is the necessary buffer of people’s nervous and intense inner experience – in the dual identities of the “real me” and the “actor”, the natural expression of the true emotion is transformed into a “performance” – hence, the “cock head man” either reveals frankly his true emotion, or need not scruple the various possible consequences from straight expression.

The “cock head man” is wearing a crude and cheap stage costume, but gives a unique color effect for the photo – in the Forbidden City 06, Chen Nong used the artificial dyed color and repaired color technologies on the black and white photographs. It was a popular exquisite polished skill in photo studios in twenty or thirty years ago. Until now, many Chinese families also preserve this kind of “photochrome”. However, it is very different from the rigorous and careful polished effects of this old photo, Chen Nong’s colored method often has freehand painting-like rough, interest and charm – summons in common a kind of era atmosphere which is rapidly vanishing. Because, “grass stage troupes” around villages and towns were just an important characterization of Chinese mass culture in twenty or thirty years ago.

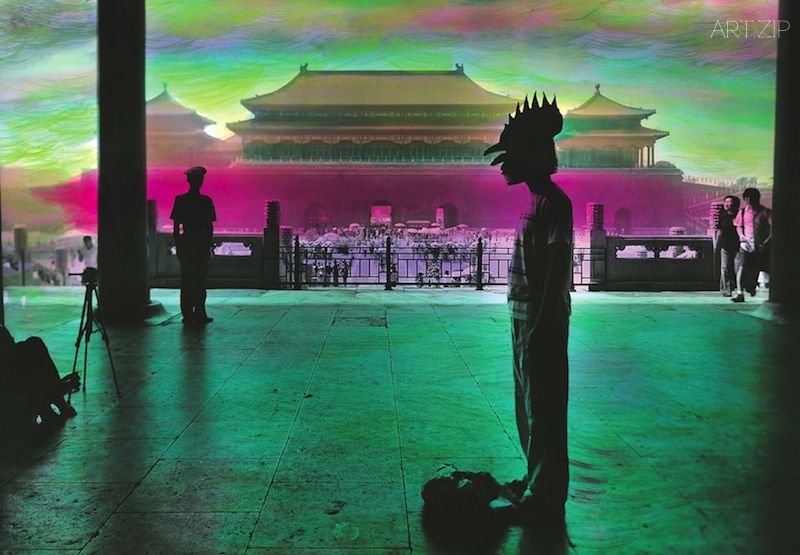

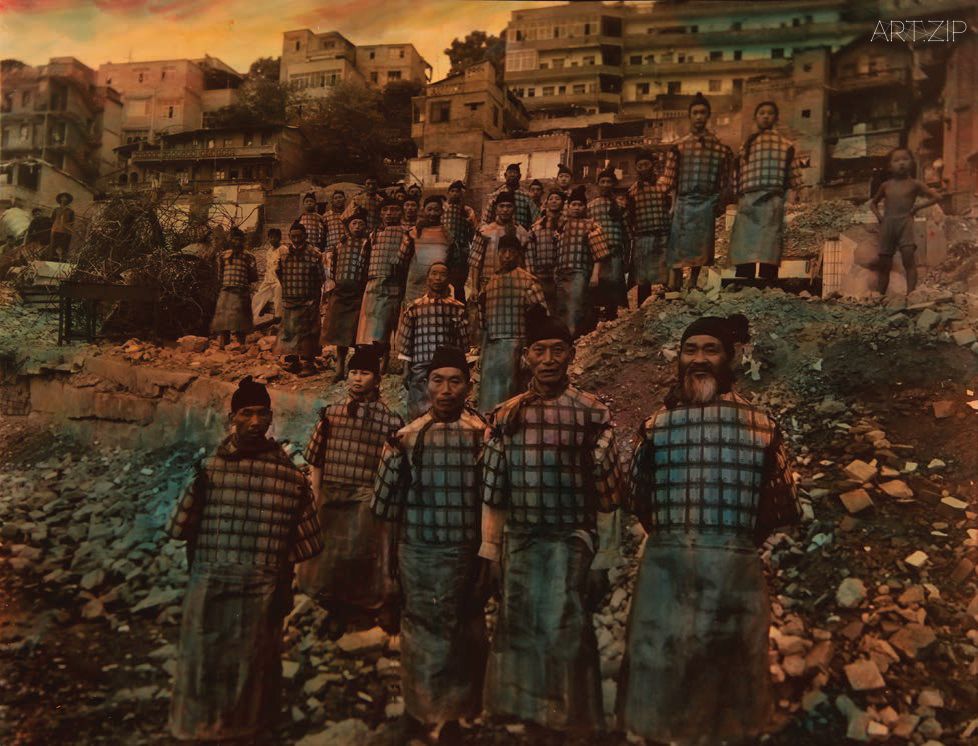

While the characters’ faces are presented clearly in the Forbidden City 02, Forbidden City 07 and other works. There are the cheap clothing in paper costumes, awkward posture, naive, perplexed and lost farm children’s faces – they are not the trained theatric actors, further are not “a bunch of angels”, look really like temporary supporting roles in the “grass stage troupe” – their identities seem very awkward in this particular scenario of the Forbidden City: they are not the master, unlike the hired labors, can not be the invited performers, or even leisurely tourists; the kind of naive expression is full of confusion and loss, also is far from the mettlesome and handsome temperament “armor” implied. Perhaps, here, are armor and wings a metaphor for already lost dreams? Are confusion and embarrassment their chilled reality? In any case, Chen Nong’s Forbidden City series are obviously different from that kind of conceptual art of mainstream values of deconstruction as the purport, they are clearly trying to present a survival reality of the “socially vulnerable groups” characterized by these farm children.

(二)

與可以隨意臆造出種種非現實的視覺幻象的當代繪畫不同,照片特有的 真實感告訴我們,“雞頭人”的雞頭、甲胄都是人工製作的道具,“他”不是 什麼怪物,而是一個將自己的真實面孔隱藏在特殊“扮相”中的人。雖然無 法確定扮演者的身份,但在這副“扮相”與具有明顯的社會隱喻的日常情境 的荒誕組合中,不僅暗示出人物與社會環境之間的精神衝突,同時,它也 是人物緊張、激烈的內心體驗必要的緩衝——在“真我”與“扮演者”的雙 重身份中,真情的自然流露被轉化為一種“表演”——於是,“雞頭人”既可 以率意地表露真實的情感,又無須顧忌直抒胸臆可能引發的種種後果。

“雞頭人”粗陋、廉價的戲裝,還與照片獨特的色彩效果——在《故宮06》 中,陳農採用了在黑白照片上人工染色的修色技術。在二三十年前,它是 流行於照相館的一種精緻的潤色技巧。直到現在,許多中國家庭還保存 有這種“彩色照片”。不過,與這種老照片嚴謹、工細的潤色效果不同,陳 農的染色往往有著寫意畫般的粗獷意趣——共同召喚出一種正在急劇 消逝的時代氛圍。因為,在二三十年前,遍及鄉鎮的“草台戲班”正是中國 大眾文化的重要表徵。

而在《故宮02》、《故宮07》等作品中,人物的面孔被清晰地呈示出來。 紙質戲裝裡的廉價服裝,笨拙的身姿,憨樸、迷茫、失落的農家子女的面 孔——她們不是訓練有素的戲劇演員,更不是“一堆天使”,倒像是“草台 戲班”裡的臨時配角——在故宮這個特定的場景中,她們的身份顯得很 尷尬:不是主人,不像僱傭的勞工,不會是受邀而來的表演者,甚至也不 是悠閒的遊客;那種憨樸的、滿是迷茫與失落的神情,也與“甲胄”暗示的 英姿勃發的氣質相去甚遠。或許,在這裡,甲胄與翅膀隱喻的是一種早已 失落的夢想?迷茫與尷尬才是她們冷硬的現實?無論如何,陳農的《故 宮》系列顯然與那種以解構主流價值觀念為主旨的觀念藝術有很大的區 別,它們顯然試圖呈現這些農家子女所表徵的“社會弱勢群體”的一種生 存現實。

Part III

Chen Nong’s photographical works are the well-designed achievement. He deliberates carefully the work theme, designs the basic visual structure, selects a specific props, finds the appropriate model, etc. before shooting; additionally he also stains on the black and white photographs, each group of photos require the corresponding basic tone, and each photo also needs different color variations, after the completion of shooting. Final effect of the photo is often an integration of absurd visual situations, malposed time-space relationship, nightmarish color atmosphere and solemn scene feeling. Obviously, regardless of creation method, image structure, inherent concept and metaphor, Chen Nong’s works should be regarded as a very typical conceptual photography.

But it seems these photos do not give the very “contemporary” visual impression. On the one hand, compared with most contemporary photographic works, they look like also leaving a lot of realistic tail: character expression, movement and basic visual scene seem to rely on too much visual characteristics of documentary photography, dyeing style and narrative intonation of photos seem also to associate inextricably with a Chinese-style realistic painting. On the other hand, these photos seem to have a kind of uncomfortable rustic taste – a common bitter flavor of “new documentary photography” in the 1980s – all of which look like to be avoided strongly by all kinds of contemporary photography.

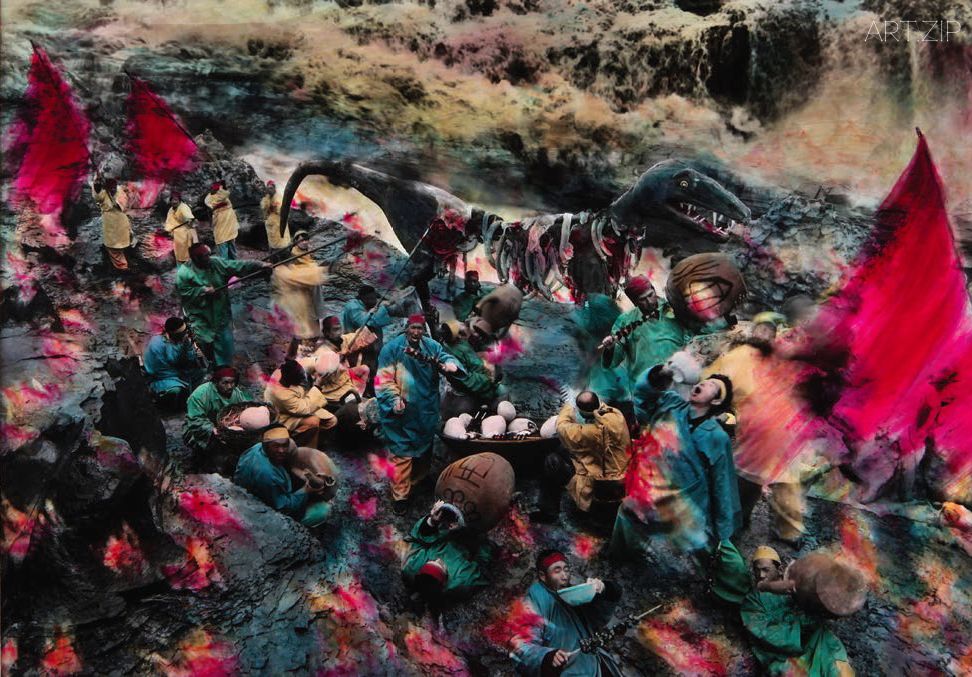

However Chen Nong does not more concern obviously “contemporaneity” of works, but a disturbing social reality –the bottom of society with the farmer as representative can not get rid of social dilemma – his unique visual language stems from his unique experience to this social problem which already becomes commonplace: misplaced characters, overlapped identities and warped sense of time and space construct a cross-era historical perspective; nightmare painting with an official realism is full of color atmosphere with snarled relationship, implies the inherent tension between a kind of social fate can never get rid of and an optimistic progressive era language; then deep poetic care eventually condenses on the wholeheartedly concern to the harsh reality after combination of absurd image structure and solemn documentary feature; furthermore that blast of bitter rustic flavor mixed in the post-modern visual imagery reflects more the artist’s keen insight to a kind of “era truth”.

From the Forbidden City series presenting and questioning on a social reality to the Mask series surveying on the rural industry filled with decline atmosphere, Three Gorges series emerging vividly on the never changed fate of the bottom of society, then Yellow River and Lotus Pond series tracing on the history of protesting this fate, and then Apsaras series playing …… on fatalistic vain effort of contemporary trying to get rid of this fate, Chen Nong’s works reflect not only beyond the grim and bitter image showing the depth of thought from the “new documentary photography” of the social reality of a representation, but also the elite attitude with a strong social rebellious mood and dispelled mainstream values, and contemporary photography with condescending wise intonation – a deeper social care and more lasting self evolution potential in a continuous concern on seemingly commonplace social reality – relative to those contemporary photography with more timeliness.

(三)

陳農的攝影作品都是精心設計的結果。拍攝之前要仔細推敲作品的主 題,設計基本的視覺結構,選擇特定的道具,尋找相應的模特等等;拍照 完成以後還要在黑白照片上染色,每一組照片都需要與之相應的色彩基 調,每一幅照片又需要各不相同的色彩變化。照片最終的效果往往是荒 誕的視覺情境、錯位的時空關係、夢魘般的色彩氛圍、以及一種冷峻的 現場感的綜合。顯然,無論是就製作方法、圖像結構、還是內在的觀念隱 喻而言,陳農的作品都算得上是很典型的觀念攝影。

但這些照片給人的直觀印像似乎並不很“當代”。一方面,與大多數當代攝 影作品相比,它們似乎還留有許多現實主義的尾巴:人物表情、動作以及 基本的視覺場景似乎都過多依賴於紀實攝影的視覺特徵,照片的染色風 格和敘事語調也似乎總與某種中國式的現實主義繪畫有著千絲萬縷的聯 繫。另一方面,這些照片似乎都有一種讓人不舒服的土腥味兒——一種 常見於八十年代的“新紀實攝影”的苦澀氣息——所有這些,似乎都是形 形色色的當代攝影所極力迴避的。

但陳農更關心的顯然不是作品的“當代性”,而是一種令人不安的社會現 實——以農民為代表的社會底層無法擺脫社會困境——獨特的視覺語 言源於他對這種早已淪為老生常談的社會問題的獨特體驗:人物錯置、 重疊的身份和恍如隔世的時空感,建構了一種跨時代的歷史視角;夢魘 般的、卻又與一種官方化的現實主義繪畫有著糾纏不清的關係的色彩氛 圍,隱含著一種從來不曾擺脫的社會宿命與一種樂觀、進步的時代話語 之間的內在張力;荒誕的圖像結構與冷峻的紀實特徵的結合,則將深沉 的詩性關照最終凝結在對殘酷現實的傾情關注;而混雜在後現代的視覺 表象裡的那股苦澀的農民氣息,更體現出藝術家對一種“時代本相”的敏 銳洞察。

從《故宮》系列對一種社會現實的呈現與追問,到《面具》系列對瀰漫著 衰敗氣息的鄉村行業的審視,《三峽》系列對社會底層從來不曾改變過的 宿命的逼現,再到《黃河》與《荷塘》系列對抗爭這種宿命的歷史追溯, 再到《飛天》系列對當代人試圖擺脫這種宿命的虛妄努力的扮演……在對 一種看似老生常談的社會現實的連續關注中,陳農的作品不僅體現出超 越於以嚴峻、苦澀的形象呈現一種表象化的社會真實的“新紀實攝影”的思 想深度,也體現出相對於那些更具時效性的當代攝影——有著強烈的社 會叛逆情緒、消解主流價值觀念的精英姿態、以及高人一等的睿智語調的 當代攝影——更深切的社會關懷和更持久的自我演化潛力。