Interview and Article by Qiwen Ke

Ambiguity and the Everyday Object

Six people, dressed in grossly patterned gowns, stand together side-by-side linking arms. Each figure clutches a coloured balloon that floats in front of them, obscuring their face. This painting, Dance Party (2015) [fig. 1], opens an exhibition of Song Yige’s work at Marlborough Fine Art Gallery, London. Song, as an emerging artist, grew up in Harbin, the Northeastern region of China, and has been working and living in Beijing since she graduated with a master’s degree in Oil Painting from Luxun Academy of Fine Arts. [i]Although exhibiting previously in Beijing, Seoul and Hong Kong, this is the first exhibition that Song has held in the UK. Her artistic journey cannot be considered without mentioning Zeng Fanzhi, one of the most influential artists in China and internationally, who first recognized Song’s talent. Zeng would go on to curate this exhibition, involved in every aspect of its production: he selected the artworks, wrote the introduction of the show and produced the accompanying catalogue. For Song, working with Zeng was indeed a once in a lifetime opportunity as he is a highly regarded artist in China in his own right.

The exhibition occupied the entire ground floor of Marlborough Fine Art Gallery for a month between 27 January – 27 February 2016. Over twenty new paintings were displayed in this exhibition, with seven paintings borrowed from private collectors. Dance Party introduces the viewer to the beginning of the show, setting the somber tone of the exhibition. On a grey-coloured background of a canvas that stretches nearly two meters wide, six attendees stand together arm in arm, dressed in dressing gowns with each of their faces concealed behind a balloon that they hold. Each gown is different: one is striped, two are floral, and the others are coloured with blues and greys. Despite expressing individuality through the different coloured and patterned gowns, this work is completely devoid of narrative, suggesting a feeling of ambiguity. This uncertainty is further caused by the deliberate obscuring of faces, a trope used by Song in other works like Her Hands (2015) [fig. 2]. If not indicated explicitly in the title, the gender of the figure in Her Hands is obscure, concealed behind a curtain – the artist simply uses a pair of praying hands to tell us that she is there. The ambiguity of Song’s work invites the viewer to question relentlessly, trying to piece together a narrative within enigmatic, often puzzling scenarios.

- Fig. 2 Yige Song, Her Hands, 2015, Oil on Canvas, 960 x 970 mm

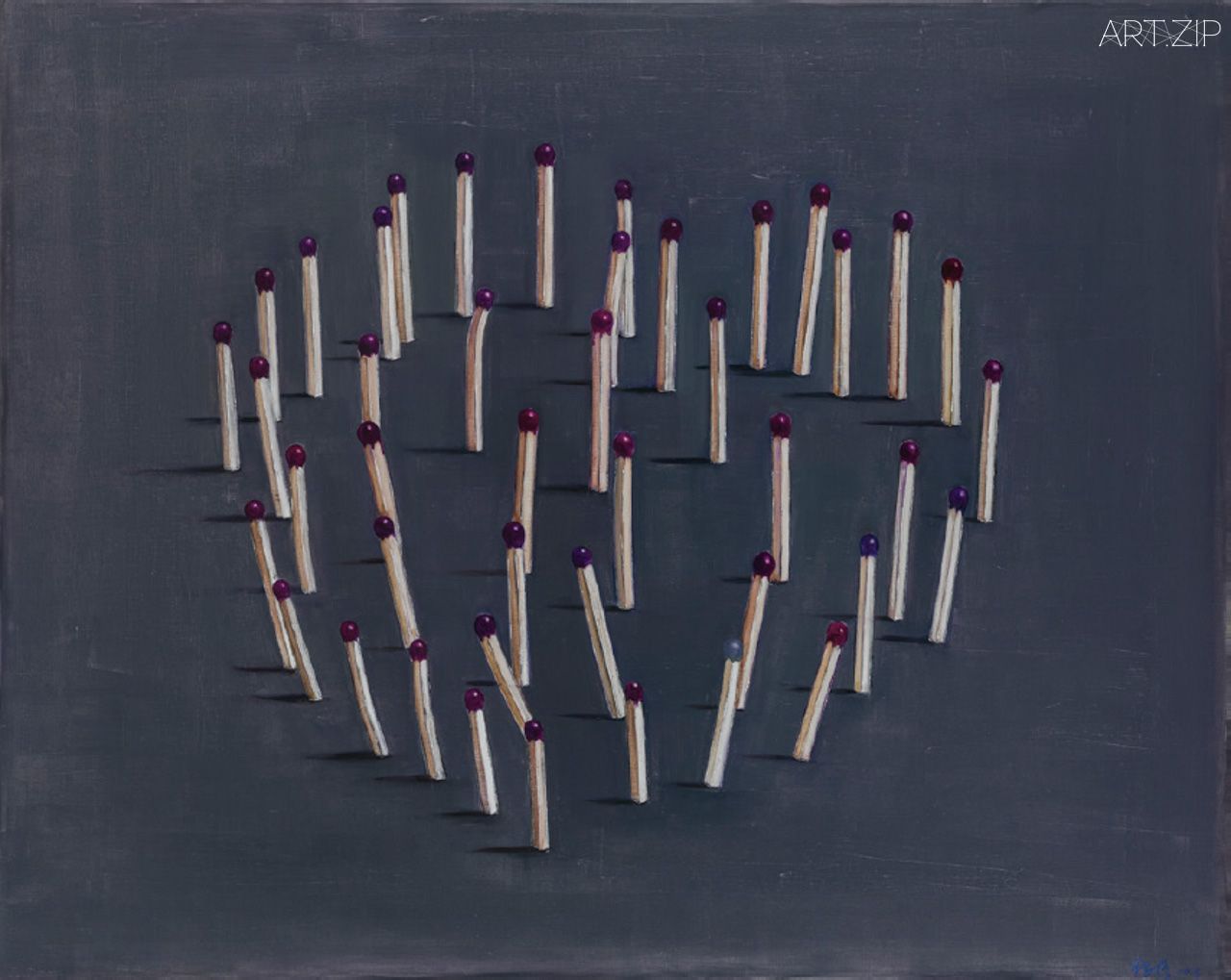

- Fig. 3 Yige Song, 43 Matches, 2015, Oil on Canvas, 1280 x 1615 mm

Song’s exhibition is dominated by the colour grey. In my interview with the artist she explains, ‘In the past, I tended to use a lot of bright colours, but at this stage, I prefer to use grey because I think it produces more layers.’[ii] The triple-coloured grey background and the dim grey-tone of the gowns create a cold, static atmosphere as if the scene has been frozen in time. Song’s use of grey recalls Gerhard Richter’s theory exploring the use of grey in paintings, ‘the ideal colour of indifference, fence-sitting, keeping quiet, despair. In other words, for states of being and situations that affect one, and for which one would like to find a visual expression.’[iii] One cannot help but recall the scenes of daily life in China, Song’s own reality, where grey is the dominant colour of urban landscapes like Harbin and Beijing, the large roads and wide pavements, the glass-clad skyscrapers, the enveloping and noxious smog.[iv]

‘Song has her own way of looking at things; even just in a tap you can see her special sense of humour. She gives life and depth to some of the most regular items’, Zeng recalls in our interview.[v] Indeed, Song’s objects are extracted from the most common things in daily life. However, when these objects come to life in her work, they communicate a sense of uneasiness, removed from their original context, despite their familiarity and regularity. The motif of the balloon in Dance Party would normally be associated with celebration, but here there seems to be no joyous occasion to celebrate; a so-called dance party – six static standing people in the bare gloomy background. The transformation of the everyday object is further seen in 43 Matches (2015) [fig. 3]. In this work, 43 matchsticks stand together to form a heart shape, each casting a left-leaning shadow. Yet, despite the seemingly organised arrangement, some matchsticks are procacriously placed; the bright pearl-like heads harbor their own source of energy which could be de-stabilised at any given moment. As a result, under such unusual circumstances, the audience is compelled to take a closer look at these familiar objects in completely new, unfamiliar contexts – an experience that is at once familiar but ambivalent, regular but disoriented, what Song describes as a ‘memory for the future.’[vi]

Women: Subjects and Objects

For Song, the transformation, redefinition and re-contextualisation of the everyday object is not only a reflection of daily life, it is further symbolic of a number of social issues such as gender, identity and class constructions. Song gives precedence to these issues by arranging objects in unfamiliar contexts in order to disrupt social ‘norms’ and instead construct alternative meanings and interpretations of daily life. The artist does so by depicting scenes ridden with contradictions and dualities in order to represent the environments as unstable, challenging the audience to look reflexively and thoughtfully at her version of the world and their place within it. In her painting Olympia (2014) [fig. 4], Song depicts a closed-in corner of a home interior where only a chaise longue and a delicately placed feather exist against a dim, grey background. This work pays homage to Manet’s 1863 version of Olympia [fig. 5]. In this version, Manet addresses the issue of spectatorship as he depicts the male spectator as the absent viewer who, signaled by the outward stare of the nude woman, is finally acknowledged.[vii] Comparing Song’s painting to Manet’s, by omitting Manet’s prostitute and replacing her with a feather, Song simultaneously communicates contradictory states of being in her painting: the notion of being both present and absent. The existence of these dualities in the same work brings us back to our previous discussion, analyzing Song’s work in terms of communicating ambiguity.

- Fig. 4 Yige Song, Olympia, 2014, Oil on Canvas, 1540 x 1380 mm, Private Collection

- Fig. 5 Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, Oil on Canvas, 1305 × 1900 mm, Musée d’Orsay

Song’s work addresses issues of female objectivity, in which objects are able to define the absent woman. In both Song and Manet’s works, an ‘object’ is offered up to the viewer for contemplation. In Manet’s work, the object is ‘both almost-respectable courtesan and shameless prostitute’[viii] whose body is laid bare before us – she is a commodity that we as spectator/client can readily consume. In Song’s work, the same thing happens: this time though, the woman is removed; it is the chaise longue that the viewer visually consumes. Yet, traces of the woman are still present in the placement of the feather. In Song’s work, although the woman’s physical body is absent from the scene, the feather left behind acts as a replacement of her body and further alludes to her caged femininity. The feather is significant as both object and female subject; it has long been associated with femininity, signifying the woman as ‘bird’. ‘The caging of the bird’, further explains Megan Campfield, ‘both literal and implied, demonstrates how women in society are subjugated by men yet still seek their own source of power within that socially accepted domination. Birds are thus representational of not only emerging feminism during the period, but a great matriarchal soul that struggles against the institutional confines of a patriarchal society.’[ix]

The feather in Song’s work can be viewed as a metaphor of the caged bird, referring both to Manet’s nude woman, but also signifying the emerging notion of feminism in the twentieth century. During this period, the status of the woman was challenged and redefined, signaled by the reform of marriage laws, education, the campaign for women’s suffrage and the improvement of the workplace.[x] To use Virginia Woolf’s concept of the ‘room of one’s own’,[xi] the female artist began to use the domestic interior in such a way to express this new-found feminist independence, largely through depicting the objects within their private rooms/surroundings. Song touches upon this phenomenon by defining the ‘feminine’ in her work through objects, perhaps referencing her own position as a female artist. Harboring resemblance to the interior of Song’s Olympia, Ethel Sands’ The Chintz Couch (1910-1) [fig. 6] is a tastefully arranged room in her home, where a chintz sofa, a wall with framed landscapes and long-stemmed white arum lilies are placed in a corner. Sand’s work furthers the idea that objects are able to define women in their physical absence. Although Sands is not in the room, her highly personal and individualistic space reflects her presence. Therefore the presence of the feather in Song’s work signifies that women have long struggled for their rights in the patriarchal society – perhaps Song is suggesting that the objectification of women still continues in present day society.

- Fig. 6 Ethel Sands, The Chintz Couch, c.1910 – 1, Oil on Board, 465 x 385 mm, Tate Collection

- Fig. 7 François Boucher, A Lady on Her Day Bed, 1743, Oil on Canvas, 572 x 683 mm, Frick Collection

The chaise longue in Olympia is displaced by Song, removed from its ‘rightful’ context within a space of luxury and opulence in order to further question/probe social issues, particularly those relating to class and social standing. The objects, a luxurious couch and decayed wall, are contradictory – they would not normally be depicted in the same scene, thus Song de-stabilises any cohesive narrative or social class stereotype. Song’s chaise longue, the engraved wooden legs and the corn yellow velvet cover, is placed in the dim corner where the wall is bare, decaying – the wallpaper flakes revealing the white plaster beneath. If we compare this work with François Boucher’s painting A Lady on Her Day Bed (1743) [fig. 7] – normally, the elegant chaise longue, like in this painting, is associated with wealth, opulence, often depicting a woman reclining dressed in gorgeous fabrics. Even in Sands’ era, replaced by a chintz sofa, a fashionable style in wealthy homes in Britain,[xii] its surrounding decoration is continuing representing a life of wealth: an eighteenth-century drawing room style wall and a modern tall stemmed, white lilies.

But not many people enjoyed the everyday life environment that Sands fortunately had, as she inherited a fortune to live independently.[xiii] The artist Gwen John, for example, in her painting A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris (1907-1909) [fig. 8], the studio is an ordinary and simple room without any decoration but the natural scenery outside the window. Rather than a couch, she picks an economic wicker chair for work use. It is clear that Song combined the chaise longue as a representation of the upper class, with the decayed, sparse room as a signifier of the lower class together in one painting. We know this object (the chaise longue) has a strong art-historical context relating to the portrayal of women in art history who are either wealthy women reclining, or female courtesans ‘fed’ to the spectator’s imagination, so this object is not random, but signifies a wider history of female portrayal in art. In other words: Song turns the world on its head, constructing an alternative reality in which our understanding of society and fixed social constructions are confused and misplaced, open to interpretation. In doing so, she sheds light on the continued social injustices that are normalized in society, forcing us as the viewer to acknowledge their existence.

Fig. 8 Gwen John, A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris, c. 1907 – 9, Oil on Canvas, 312 x 248 mm, National Museums & Galleries of Wales

Legacies of Masculinity

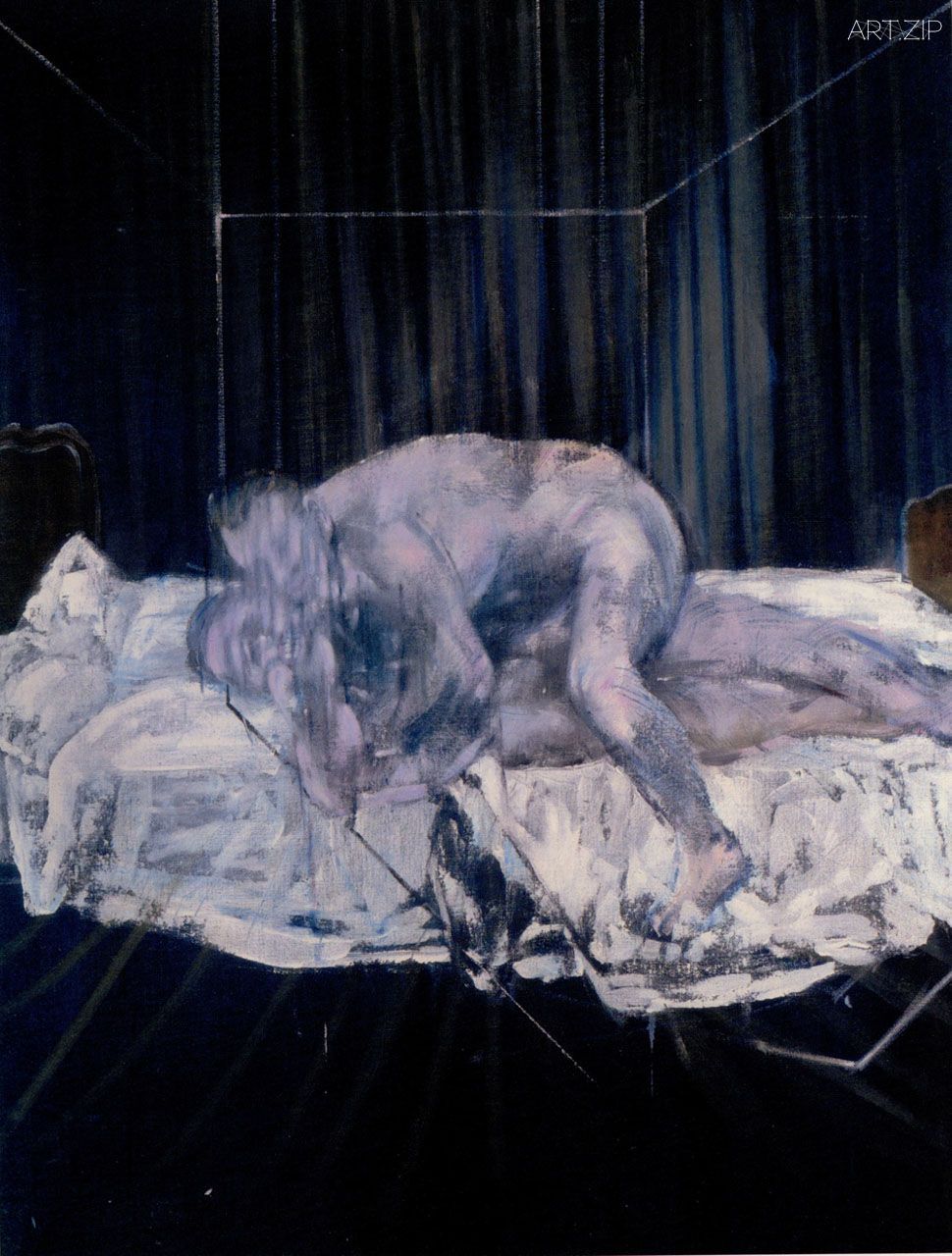

In addition to utilizing and transforming symbolic objects in order to highlight social issues in her work, Song borrows motifs directly and overtly from other artists. In her painting Twins (2015) [fig. 9], Song references two seminal works in Western art history; motifs from Michelangelo’s Rebellious Slave (1513) [fig. 10] and Francis Bacon’s Two Figures (1953) [fig. 11] are combined in her work. She has duplicated two identical versions of the Rebellious Slave, tied them up in purple rope and then placed them in a prison-like setting on a stage. Song’s twins, the two sculptures, are reinterpretations of Bacon’s two male nudes; the space they occupy in her painting further echoing Bacon’s linear cube. The colour palette Song uses also resembles Bacon’s white tone figures/objects, and white lines marking the boundaries of a dark space, tense and hostile.

- Fig. 9 Yige Song, Twins, 2015, Oil on Canvas, 1737 x 1990 mm

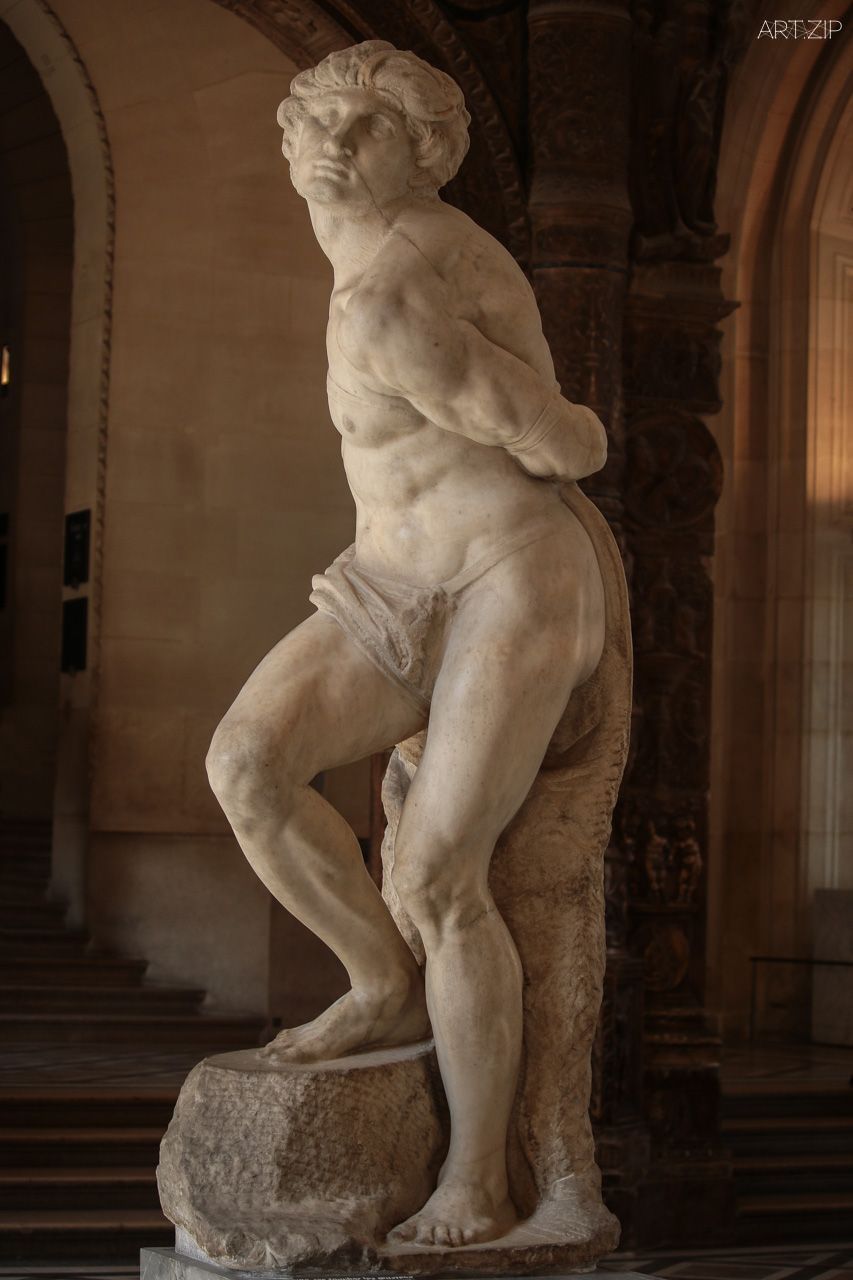

- Fig. 10 Michelangelo, Rebellious Slave, 1513, Marble, H. 2090 mm, Louvre Museum

Twins raises and challenges normative gender positions that construct specific assumptions of masculinity. In this work, Song deals with the idea of the ‘male body’, which was a common motif in Michelangelo’s sculptures and in Bacon’s paintings. Described as ‘the first person since the great days of Greek sculpture to comprehend fully the identity of the nude with great figure art,’[xiv] Michelangelo injects strength and beauty into the perfect physique – the delicate facial features, the accentuated muscular frame, and the proud genital (a symbol of sexual privileges and power)[xv] – exemplifying the traditional construction of masculinity. Although admittedly drawing on the voluptuous male nude Michelangelo made,[xvi] Bacon’s image of masculinity in Two Figures is unconventional – contorted bodies, disjointed heads and blurred faces – showing the figures as shameful, fragmental and unattractive. In doing so, Bacon fights against the stereotypical discourse of masculinity.[xvii] In the self/other discourse, there exists a power dynamic where the ‘other’ (social construction) has more control over the ‘self’ (subject); in other words, the ‘self’ is subject to gender stereotype.[xviii] Different from bacon’s deconstruction, Song intentionally comes back to the original historical context. She replicates the traditional construction of masculinity in Michelangelo’s sculpture into the painting. The sign of the tradition of masculinity is stability, control, action, or production.[xix] By showing these bodies as ambiguous, in turmoil, fragmented and therefore unstable, Bacon’s Two Figure is a resistance to objectifying transformations of a stereotypical discourse. This resistance is also evident in Song’s Twins. By selecting the rebellious slave as her subject matter, she replaces its original sling with a longer, more sensual looking purple tie to arouse a tension between imprisonment, rebellion and sexuality. She presents the male body as caged in this hostile environment, imprisoned, but at the same time the rope signals a kind of erotic restraint – perhaps referencing ongoing issues of masculinity/ the male body type in present day society.

By depicting two male nudes positioned in this way, Song further probes issues of homosexuality. Like Bacon’s work, her figures are caged and restricted within a void-like dark space where the emptiness of the space leaves the painting devoid of narrative. As Robert Hughes suggests, the generalized environment stresses the analogies between the body’s various availabilities when in scenarios of abandonment and lack of control: to inspection, sex or political coercion.[xx] In Bacon’s Two Figures, he uses this method to transform the raw statement ‘Men Wrestling’ in to a carnal image of men mating.[xxi] By exposing their physical desire and animal passion through the motion of the mouth and the bodies, Bacon places the human on the same level as the beast, and thereby he eliminates any sense of social propriety.[xxii] Through the form of fragmentation, the inner ‘self’ in its whole, most genuine form takes over the ‘other’. A real desire becomes visible and completely free from social regulation. The prison structure is also a symbol of mental imprisonment associated with suppressed desires that are further cause by social regulation and alienation. This association between imprisonment and homosexuality is particularly relevant, as it was not until 1967 that homosexuality became legalized in the UK, more than a decade after the completion of the Two Figures.[xxiii] Today, the LGBTQ community continues to strive for social equality in a world that is still largely dictated by normative social behaviour. Song is therefore engaging with important ongoing societal issues, and by using the rebellious slave and the prison motif she alludes to an ongoing ‘rebellion’ itself.

In my interview with Song, she acknowledges her engagement with Bacon, who she believes is her spiritual mentor since she was a child.[xxiv] Holding her solo exhibition in the same gallery where Bacon has exhibited is no doubt the biggest recognition in her career so far. Yet, although Song references Bacon’s work, Bacon’s images attempt to evoke a violent, direct response in the onlooker,[xxv] whilst Song favours ambiguity, indirectness and intrigue. From Michelangelo to Manet, Bacon and beyond, Song combines motifs that look cross-historically and cross-temporally, de-stabilising a chronological narrative of art history defined by periodisation. Her artwork is determined by a context that is not stable; she uses past contexts to produce new contexts. On the one hand, she demonstrates the interrelated nature of ongoing issues in history; on the other, by removing the barriers of time and space in her image, she asks the spectator to understand her work from a cultural standpoint outside of its original context.[xxvi] Based on each individual experience, the act of looking at one of Song’s paintings is to look reflexively at one’s self and our position within a re-defined reality.

Song’s work probes us to look at our experience of history and of time in completely new and refreshing ways, acknowledging the complexity and uncertainty of our world, and what it means to produce art in the modern era. The diversity and ambiguity of identities undoubtedly at play in Song’s work further complicates our understanding of knowledge and given ‘truths’, and this idea of ‘truth’ can be further extended to the curation of the exhibition itself, especially when comes to the discussion of authorship. This exhibition was curated by Zeng in a Western commercial gallery, and if we consider the nature of the works that he chose to display, it becomes clear that he selected works that would appeal to a Western audience, guiding the viewer into a context that he constructed. This is perhaps one of the problematic aspects of curating a non-Western artist abroad that many contemporary artists are facing today. How do we acknowledge and display works without divorcing them from the cultural conditions in which they were produced? We need to look at works of overseas artists from the perspective/lens of their cultural contexts and created new dialogues and conversations between works within an exhibition space to facilitate diaspora contexts and cultural exchange. We must therefore see this exhibition as a whole, potentially as a reflection of Zeng’s reality, and if it is his reality, then we can’t help but ask the question who exactly is the author of this exhibition: the artist, the gallery, or the curator?

[i] For the purpose of this article, Song Yige and Zeng Fanzhi will be referred to as ‘Song’ and ‘Zeng’. This ordering reflects the Chinese sequence of names, and is used throughout the exhibition.

[ii] Qiwen Ke, An interview with Song Yige, Marlborough Fine Art London, 27 January 2016.

[iii] Gerhard Richter, Interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker, 2004. https://www.gerhard-richter.com/en/quotes/subjects-2/grey-paintings-9, accessed on 15 August 2017.

[iv] Lily Le Brun, ‘Introduction’ in Song Yige exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art London, 2016, p.9.

[v] Qiwen Ke, An interview with Zeng Fanzhi, Marlborough Fine Art London, 27 January 2016.

[vi] Ke, An interview with Song Yige.

[vii] Alexander Nehamas, Only a Promise of Happiness: The Place of Beauty in a World of Art, Princeton 2007, p.119.

[viii] ibid, p.108.

[ix] Megan Campfield, Caged Birds and Subjugated Authority: A Study of the Thematic and Historic Significance of Bird Imagery Within the Works of Fanny Fern, Kate Chopin, and Susan Glaspell, 2009, p.3.

[x] Nicola Moorby, ‘Her Indoors: Women Artists and Depictions of the Domestic Interior’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/nicola-moorby-her-indoors-women-artists-and-depictions-of-the-domestic-interior-r1104359, accessed 22 August 2017.

[xi] Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, Michèle Barrett (ed.), London 1993, p.3.

[xii] Nicola Moorby, ‘The Chintz Couch c.1910–11 by Ethel Sands’, catalogue entry, September 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/ethel-sands-the-chintz-couch-r1136824, accessed 24 August 2017.

[xiii] ibid.

[xiv] Frank Zöllner, Michelangelo. Complete Works, Cologne 2017, p.38.

[xv] Ernst van Alphen, Francis Bacon and the Loss of Self, London 1992, p.178.

[xvi] Zöllner, Michelangelo, p.44.

[xvii] Alphen, Francis Bacon and the Loss of Self, p.190.

[xviii] ibid, p.164.

[xix] ibid, p.190.

[xx] Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New, London 1991, p.298.

[xxi] Hugh M. Davis, Francis Bacon: The Early and Middle Years, 1929-1958, New York 1978, p.150.

[xxii] Rina Arya, Francis Bacon: Painting in a Godless World, London 2012, p.137.

[xxiii] ibid, p.148.

[xxiv] Ke, An interview with Song Yige.

[xxv] Alphen, Francis Bacon and the Loss of Self, p.166.

[xxvi] Michael Hatt and Charlotte Klonk, Art History: A Critical Introduction to its Methods, Manchester 2017, p.2.