TEXT BY 撰文 X XIAOHUI GUO 郭小暉

TRANSLATE BY 翻譯 X EVELYN LIU 劉楚翹

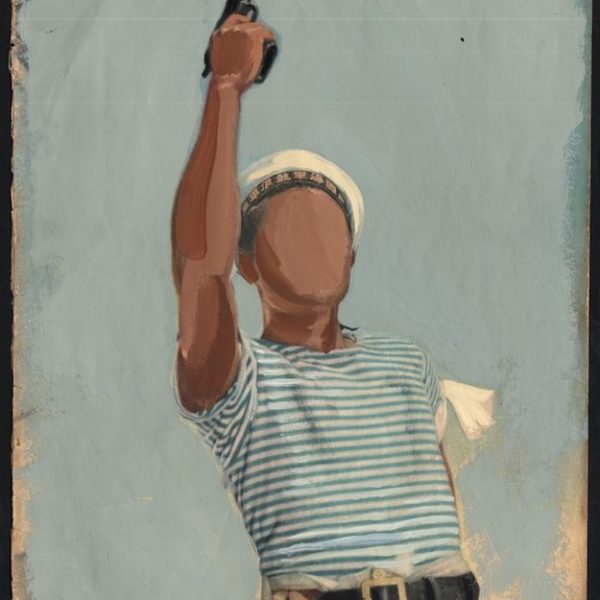

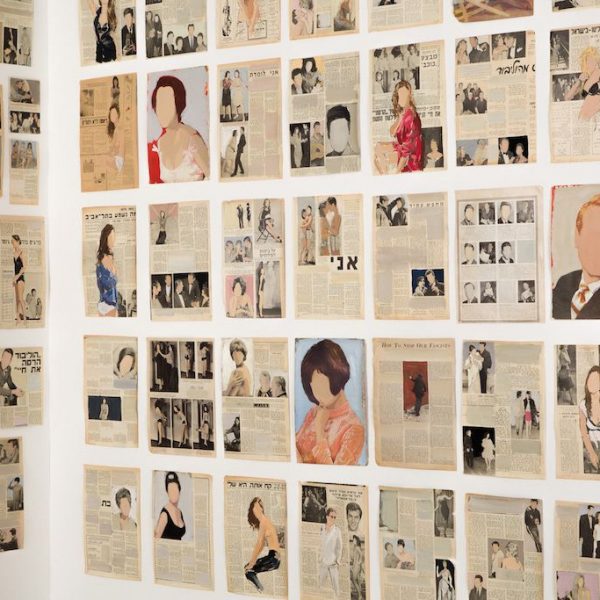

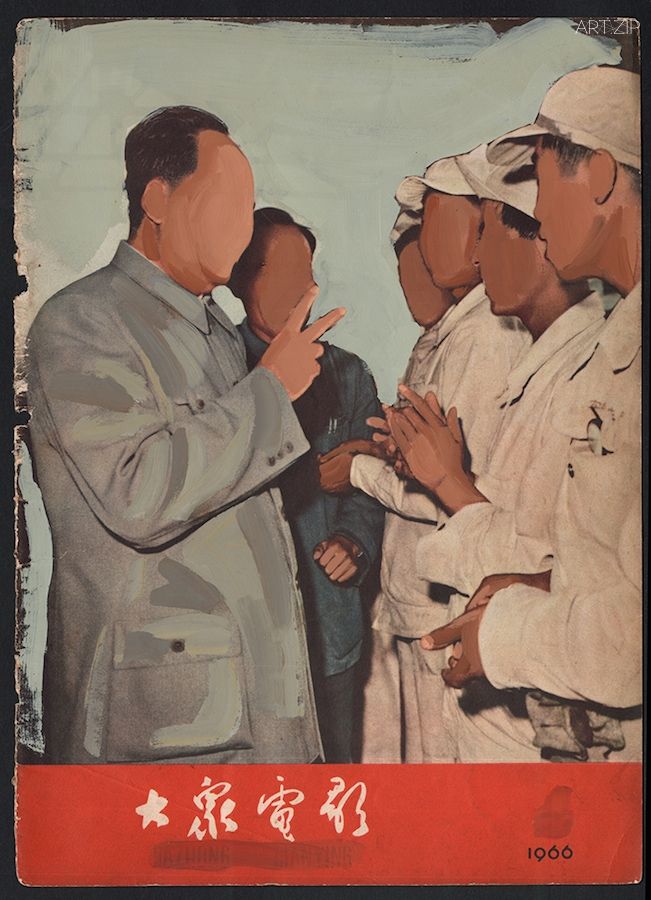

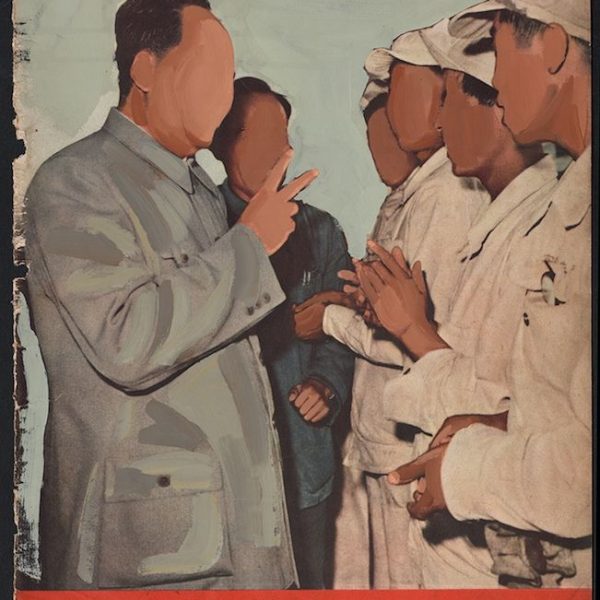

The title Gideon Rubin: Memory Goes Far as This Morning, is that of the first museum solo show of Israeli artist, Gideon Rubin exhibited at the Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art, one of Israel’s upcoming contemporary art museums. It displayed works created by Gideon Rubin during two art residencies in Tel Aviv, Israel and in Shenzhen, China, in 2014. The artist used old magazines and newspapers as the foundation or backdrop against which to create his imagery. As he commented in an interview in regard to his repetitions : “I have made a couple of hundred newspaper paintings – it allowed me to work these forgotten images, could they still be of value? As obsessed as I am with all sorts of imagery: gossip, political etc., painting from and on photographs is my attempt to slow the image down, to hold it for a little longer and allow a second, more sustained observation.”

Like many artists of his generation freely moving between countries and different cultural regions, this diversity has become an inextricable part of his cultural background. Born in Israel and having passed his adolescence there, Rubin later studied at the School of Visual Art in New York and at the Slade School in London. He is currently residing in London with his wife Silia Tung, a former classmate and an artist.

Like many artists of his generation freely moving between countries and different cultural regions, this diversity has become an inextricable part of his cultural background. Born in Israel and having passed his adolescence there, Rubin later studied at the School of Visual Art in New York and at the Slade School in London. He is currently residing in London with his wife Silia Tung, a former classmate and an artist.

The title of the exhibition derives from a quotation from a poem by the well-known Chinese poet Bei Dao:

Who believes in the mask’s weeping? Who believes in the weeping nation? The nation has lost its memory Memory goes as far as this morning Memory and history, just as the title implies, have been Rubin’s primal concern. What kinds of history and memory are we facing? And, how do we claim responsibility in regard to them? These dilemmas seem to be the keys to his narrative.

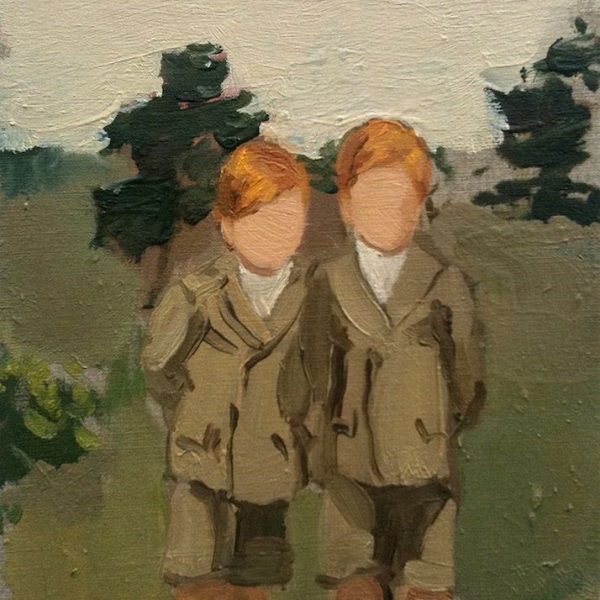

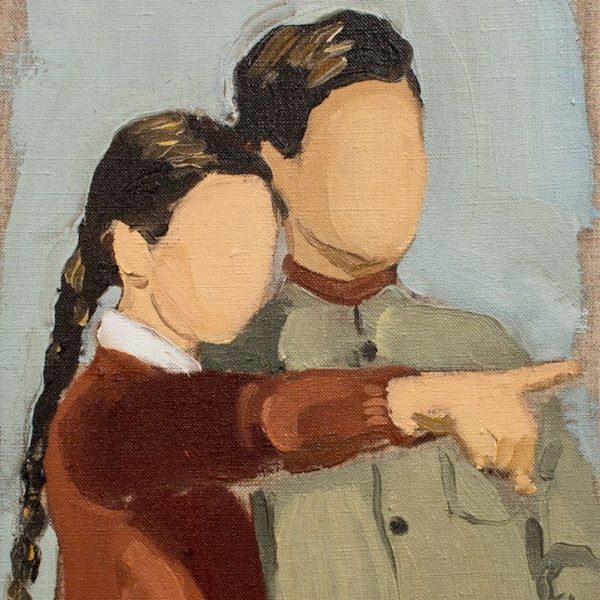

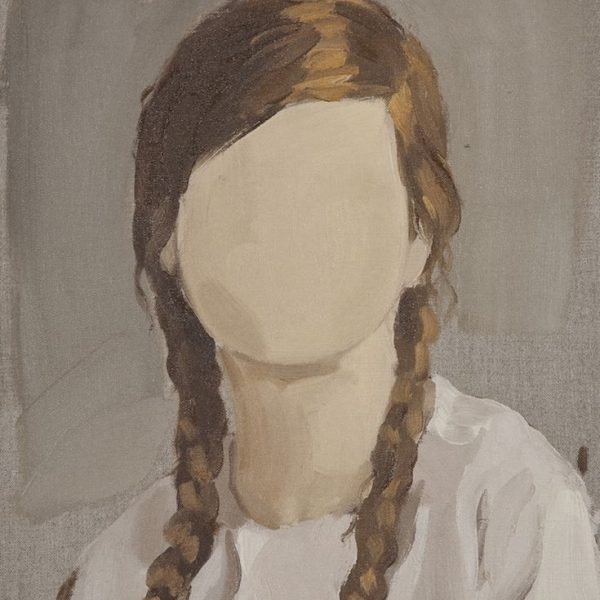

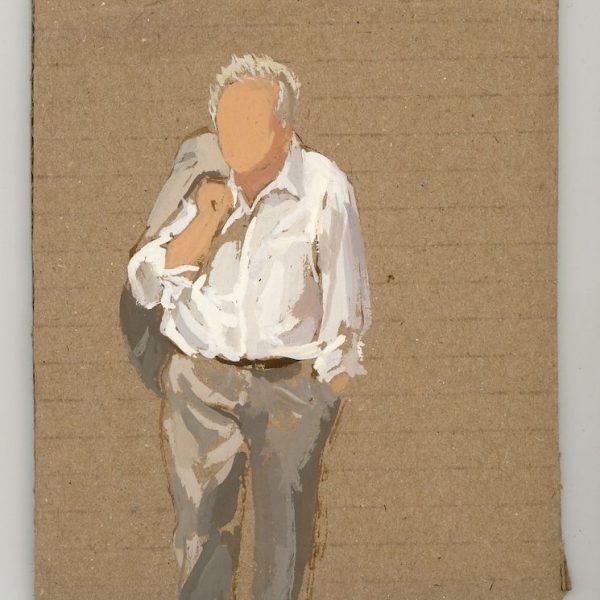

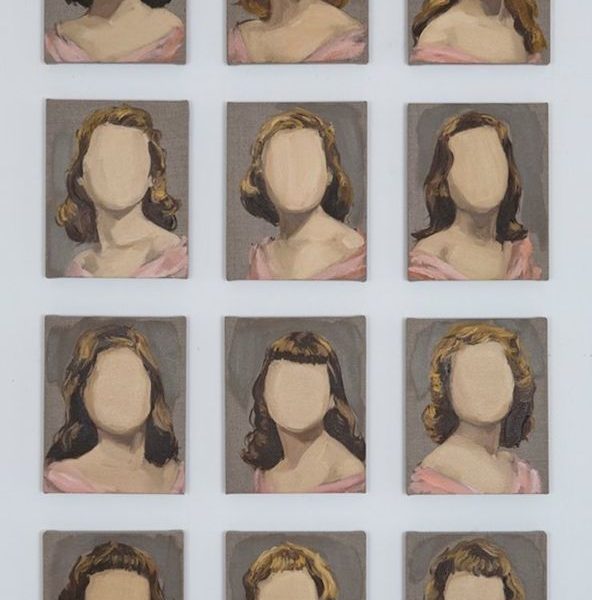

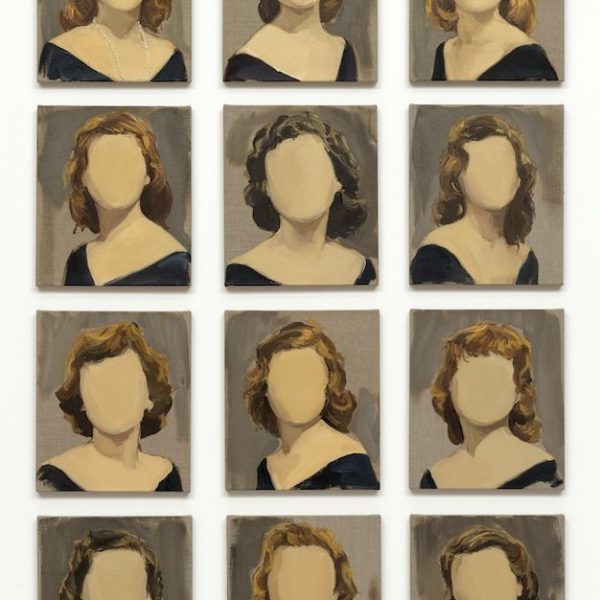

Portraiture is the subject-matter that Rubin mostly focuses on. The people inhabiting his paintings can be associated with a kind of loss or disillusionment. He constantly depicts them paying attention to their body language and eliminating their facial features. A boy and a girl standing in front of a mirror, each holding a flower; brother and sister playing together; a boy sitting on a tree-trunk; sisters playing on the beach by the water; a girl with a dog in her arms; two young women rowing a boat; a fair lady wearing an off-the-shoulder dress as well as the backs of numerous young girls… these protagonists all seem to have one thing in common – their facial features are absent.

Since we are not able to see their faces, they are anonymous, thereby becoming ‘others’. In this way Rubin allows the viewer to be himself the storyteller, all-the-more-so with the poignant atmosphere conveyed by his tender tonal colour combinations. The viewer’s vision is furthered by the mild, muted colors, which seem to transport us to distant places, linked to our thoughts and recollections. Why are human faces the eternal subject of painting? this has always been a topic of discussion for scholars. Emmanuel Levinas remarked on the subject that the face of the ‘other’ made certain moral claims upon us, yet we have no way of understanding what these claims are. “The approach to the face”, he wrote, “is the most basic mode of responsibility…The face is not in front of me (en face de moi), but above me; it is the other before death, looking through and exposing death…To expose myself to the vulnerability of the face is to put my ontological right to existence into question. In ethics, the other’s right to exist has primacy over my own, a primacy epitomized in the ethical edict: “thou shall not kill, thou shall not jeopardize the life of the other” 1

In his essay Peace and Proximity, he further points out that “The face is to be found in the back of the neck… The “face” seems to persist in a series of displacements such that a face is figured as a back” 2 The back can therefore also be interpreted as “the extreme precariousness of the other”. Understanding faces means to grasp the vulnerability of life, which itself is the result of grasping the precariousness of others.

In a similar way, the featureless faces that Rubin paints, provide us with the opportunity to experience the precariousness of the ‘other’. His featureless faces are not some kind of blur or oblivion. On the contrary, when we try to recall someone’s likeness – sometimes with great effort – we may find out that the facial features remain vague. We may even fail to remember any clear image, but that absence of faces in Rubin’s paintings seems to provoke our memories. It causes our minds to slow down in front of his works, as it were, so that distant memories may simultaneously re-emerge. As Derrida states in The Other Heading: “We cannot and must not forget them since they do not forget us.”3

History and memories have thus been reproduced and rekindled. With Rubin’s reinterpretation, these nameless people from old magazines and discarded newspapers have become the vessels in which our personal and collective memories come together. Like other Jewish scholars, Rubin too is inevitably equipped with that deep concern with history and memories. Jewish tradition for him is not about religious observance but rather about cultural heritage.

Walter Benjamin, the leading philosopher, dedicated his work to the relationship between history and salvation. For Benjamin the completion of history is not realized by history itself, it must be exercised by the Messiah. ‘Messianic days’ is a new form of time, a tensile cord between birth and disappearance, fulfilment and un-fulfilment of history.

Therefore, the Messiah time represents a reminder, the arrival of the ‘other’. It demands to pull the past into the now-time through history. Only in that way can the present capture history from memories, thereby amending the misfortunes of the past and releasing a new potential. Translation is the principle of salvation. The precious language traditions scatter around and hide amidst literary arts and cultural landscapes and they can only be revealed through translation.

In that sense Rubin’s paintings are a translation of sorts. Through reinterpretation and revision the works are endowed with new possibilities: slowly our memories and emotions relating to others are rekindled. Rubin’s gentle colours reflect his hesitation and anxiety in regard to touching the canvas, creating with his brushes images which have otherwise brought us a sense of exigency.

As Agamben wrote in The Time that Remains: “Exigency does not properly concern that which has not been remembered; it concerns that which remains unforgettable. It refers to all that is forgotten in individual or collective life with each instant, and to the infinite mass that will be forgotten by both.” 4

The absent faces of Rubin’s works would have represented the unforgotten exigency. This exigency is most potently reflected in one of his rare landscape paintings: House in Wannsee (2005) painted from a famous photo documenting the house where Reinhard Heydrich, the head of the Gestapo, summoned Germany’s high officials on the 20th of January 1942, to draft the Nazi “Final Solution”, ‘upgrading’ the rapidly escalating persecution of European Jews to total annihilation.

Rubin painted the buildings’ windows black, communicating an evil darkness, consequently transporting the people carrying this historical memory back to the nightmare. Referring to Agamben again – since no other sentence has resonated as much with the feeling that Rubin’s painting arouses in us – “Exigency does not forget, nor does it try to exorcise contingency. On the contrary, it says: even though his life has been completely forgotten, there is an exigency that it remains unforgettable.” 5

展覽《當記憶成為早晨》展出了吉迪恩·魯賓(Gideon Rubin)的兩個藝術家駐留項目的作品。兩個駐留項目分別是魯賓於2014年在以色列特拉維夫和中國深圳所做的藝術家駐留項目的作品。此次的展覽作品則是魯賓重復采用過多次的媒介——舊的書刊報紙,而且他已經利用這個媒介創作了上百幅作品。正如藝術家自已所說的,“這種重復讓我可以在這些被遺忘的圖像上重新工作,讓我思考他們是否仍有價值?我迷戀各種各樣的題材:像八卦,政治等等。這些來自舊照片的圖像,或者有時我直接在舊照片上繪畫,我嘗試放慢閱讀圖像的速度,盡量保持時間長一點,使我可以更持久地打量它們。”

同他的大多數同時代藝術家一致,不斷地在不同的國家和文化地區轉換和生活早已經成為他藝術實踐背景中的不可或缺的一部分。吉迪恩在以色列出生並度過他的青少年時期,接著先後分別在美國紐約視覺藝術學院(School of Visual Arts)和英國倫敦大學斯萊德美術學院(Slade School of Fine Art,University College London)接受美術教育,目前則與他的中國裔妻子,同樣是一位藝術家也是他的同學Silia Tuang,生活居住在倫敦。

展覽的題目是中國詩人北島一首詩歌的題目《當記憶成為早晨》。詩歌的第一段這樣寫到:

誰相信面具的哭泣

誰相信哭泣的國家

國家失去記憶

記憶成為早晨

正如此次展覽的題目所涉及的,記憶和歷史是魯賓始終關切的問題。當記憶和歷史總成為最為關切的問題時,面對何種歷史?面對何種記憶?又如何對它們負責?這成為表述的關鍵。

人物始終是吉迪恩關注的題材。他畫中的人物,可以說與一種丟失或者失落相關,他不停地一遍一遍描繪著他們,他們的動勢,他們的面孔。而且很顯然,婦女和兒童是重點描繪的對象。手中拿著一朵花,面對鏡頭站立的小男孩和小女孩,正在玩耍的的姐弟,坐在樹上的小男孩,在海灘上戲水的姐妹, 抱著狗坐著的小女孩,正在劃船的二個年輕婦女,一位身著露肩晚禮服的名媛,以及很多年輕女孩的背影…這些人物都有著一個的共同點——他們的面孔缺席了。

這就是吉迪恩所描繪的面孔,與我們常見到不同,他筆下的人物,要麽面孔全部是缺席的,要麽就是背影。因為我們無從看到他們的面孔,因此他筆下的人物成為真正的匿名者,從而成為完全的他者,因而魯賓使得觀者成為完全意義上的作者;隨著他柔和的,朦朧的色彩方案傳所達出的一種悲傷的氣氛,它模糊了你的視線,消除了你對明亮清晰的色彩的緊張感和隨之而來的警惕感。使得你的視線隨著這些柔和而朦朧的色彩仿佛去到很遠的地方,這個地方與你的思緒有關,與你的記憶相關,從而完成了你記憶的一個回閃,一段旅程。

為何關於人類的面孔是繪畫永恒的題材?這同樣也是眾多學者一直以來關注的問題。就這個問題,伊曼紐爾·列維納斯(Emmanuel Lévinas)曾經做過詳細的描述。在他看來,“他者“的面孔向我們提出了倫理要求,但我們無從知曉這一要求究竟是什麽。列維納斯他寫到:“接近‘面孔’乃是最為基本的責任模式……面孔並非在我面前,而是在我之上;它是頻臨死亡、洞穿死亡、揭露死亡的他者。……直面面孔脆弱性意味著質疑我本體層面的生存權。在倫理學中,他者的生存權優先於我自身的生存權,這一優先性可用如下倫理律令概括:不得殺人,不可危及他人生命。” 進而,他在一篇《和平與切近(Peace and Proximity)》的文章中,列維納斯指出,從人們的脊背,頸項等部位我們也能找到“面孔”的蹤跡,雖然這並非通常意義上的面孔。因為這些部位等同於面孔想要傳達的含義,既“面孔,他者的極度脆弱性。”因此,理解面孔也就意味著領悟生命本身的脆弱不安,而且必須是首先領悟他者生命的脆弱性。

對於魯賓來說,他筆下的面孔正如列維納斯闡釋的那樣,那些孩童的,女性的面孔,但卻是面部特征缺席的面孔,給我們帶來了這個體會他者之脆弱不安的可能性。他筆下的人物面孔的缺席並非是他想制造一種模糊和遺忘,而是與之相反。就如當我們極力地想記住一個人的面孔時,卻發現我們反而覺得我們拼命想要記住的面孔所有清晰的特征都變的模糊甚至我們根本想不起來一個清晰的圖像。所以,魯賓缺席的面孔反而給我們的記憶打開了一個入口。是我們得以在他的畫面前,放緩我們的思緒,使得我們可以仔細地端詳之余,仿佛來自遙遠記憶劃過我們的腦海,使我們一一回想起來。正如雅克·德里達(Jacques Derrida)在《另一頭/另一個海角:記憶,回應,責任(The Other Heading: Memories, Responses, and Responsibilities)》所提醒我們地那樣,“我們不可以並且不能忘記它們,因為它們不曾忘記我們”。

歷史和記憶就這樣被重現了和喚起了,通過魯賓的重新“翻譯”,這些來自舊照片以及舊雜誌與舊畫報中的無名者,帶著我們集體和個人記憶在這裡相會了。

在這不得不提及猶太文化傳統。作為猶太人,魯賓也毫無例外地與所有的猶太人知識分子一樣,有著最大的一個共同點——對歷史和記憶的關切。猶太傳統特有的彌賽亞情結(Messiah)和卡巴拉闡釋學(Kabbalah),對魯賓來說,早已並非一種宗教現象而是一種關於歷史的敘事傳統。

瓦爾特·本雅明(Walter Benjamin)可以說是這一思想的典型代表學者,他一生著眼於探究歷史與救贖的關係。在他看來,歷史的完成並不是歷史自身能夠實現的,必須由彌賽亞來實施。對本雅明而言,彌賽亞是試圖創建一種新型的時間,是一種歷史的生成與消失、實現與未實現之間的張力結構。彌賽亞時間將這種張力凝聚在“當下”。所以,彌賽亞時間在這代表了一種剩余,是不可化約的他者的到來,它要求通過記憶,將過去拉入當下。這樣,當下才能對歷史提出要求,並在在記憶中將其捕獲,從而達到一種對過去的不幸的修復,並且釋放和產生出一種新的潛能。而翻譯,正是本雅明提出的救贖法則。在他看來,那些珍貴的語言“傳統”呈碎片狀地散落和隱藏在文學藝術、文化景觀之中,只有通過“翻譯”才可將其顯現出來。

從這個意義上來說,魯賓的繪畫就是一種翻譯。他通過對舊照片重新描繪和修訂,允許和提醒我們更加仔細和緩慢地進行觀看,在這個被魯賓重新賦予了一種新的可能性的畫面前面,重新喚醒了我們記憶, 以及對他者的感受。

因為如此,他的這種色彩輕柔,幾乎有時你可以感到藝術家不願落下筆觸的猶疑和焦慮,反而帶給我們一種迫切性。正如喬治·阿甘本(Giorgio Agamben)在他的一部著作《剩余的時間中(The Time That Remains)》指出的那樣,“迫切性不完全是關於沒被記住的事物,它關涉的是始終不可遺忘的東西。它指的是所有在個體或集體生活中被遺忘的瞬間,指的是個體和集體都會忘卻的無限的大眾。”在這個意義上,吉迪恩缺席的面孔正代表這種不可遺忘的迫切性。

這種迫切性更為強烈地體現在他少有的一幅《萬湖別墅(Wannsee House)》的作品中。圖像來自一張著名的歷史照片,這是一個具有特別意義的建築,正是在這所建築物中,納粹德國於1942年1月20日,由秘密警察首領海德里希(Reinhard Heydrich)召集了德國高級官員,研究大規模系統地屠殺猶太人的計劃,會議通過“最終解決猶太人問題”的決議,提出“最終解決”的辦法。這次會議成為把對猶太人的迫害升級到最終從肉體上消滅的標誌。

在魯賓的版本中, 他把所有窗戶都塗黑了,我們可以感受到一種來自黑暗的力量,把所有攜由這段歷史記憶的人們重新帶進一種噩夢般的記憶中。讓我再次引用阿甘本所說的一段話,因為沒有比這段話更為精確的表述魯賓想要帶給我們的感受:“失落的事物之迫切性並不蘊涵著需要什麽紀念的意思;反之,它蘊涵的意思是,那些東西持留在我們之中並以遺忘的方式和我們待在一起,並且僅以此方式,成為始終不可遺忘的事物”。