TEXT BY 撰文 x SOPHIE GUO 郭笑菲

IMAGES COURTESY OF 圖片 x GAGOSIAN GALLERY 高古軒畫廊

Michael Craig-Martin CBE RA curates explosion of colour in Gallery III of the Summer Exhibition 2015 © David Parry, Royal Academy of Arts

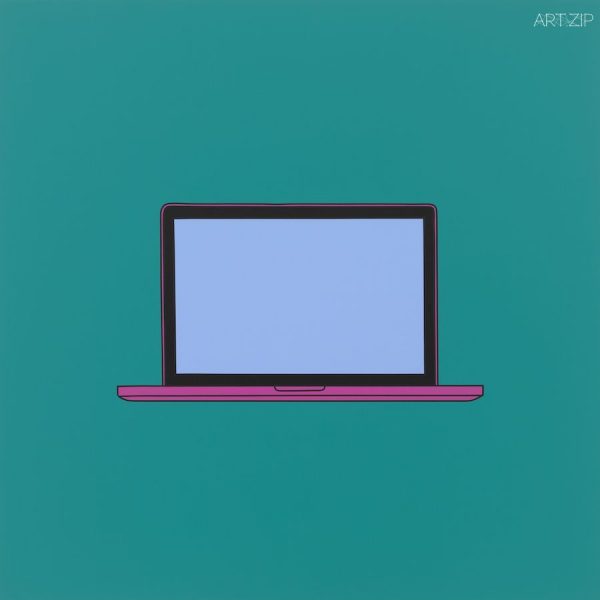

“Art is more to do with observation than invention.” Carefully teasing out the globally recognised yet the most easily ignored everyday objects with bright and arresting colour, the British artist Michael Craig-Martin has orchestrated a visual symphony of modern material life in his debut exhibition in China. Entitled Now, the touring exhibition marks the beginning of the ‘2015 UK-China Year of Cultural Exchange’.

As a prominent figure of the British contemporary art scene, Craig-Martin was first known for his conceptual work, An Oak Tree, which established the artist as one of the key figures in the first generation of British conceptual artists. In the late ‘70s, everyday objects came to the heart of his artistic creation. They were displayed in simple form and bold colour, with great visual stimulation. Apart from his role as a leading artist, Craig-Martin was also an important art educator who inspired the Young British Artists (YBA), including Gary Hume, Damien Hirst, and Sarah Lucas. Awarded a CBE in 2000 and elected a Royal Academician in 2006, Craig-Martin has been playing crucial roles in public art programmes on national and international level, including co-curating the well-acclaimed Summer Exhibition 2015 at the Royal Academy and judging the John Moores Painting Prize China.

“藝術不止是創作,更與觀察緊密相連。”英國藝術家邁克爾·克雷格-馬丁(Michael Craig-Martin)將我們生活中易被忽略的日常用品用抓人眼球的明快色彩小心勾勒出來,並用這些材料在他的首次中國巡展中排演了一部關於現代物質生活的視覺交響。這次巡展代表了“2015年中英文化交流年”文化項目的啟動。

克雷格﹣馬丁是英國當代藝術的標桿人物。他最初由《一棵橡樹(An Oak Tree)》而為人所知,而這件觀念作品也奠定了他在第一代英國觀念藝術家中的重要地位。七十年代末,日常生活用品開始成為他創作的核心,它們在他作品中常以極簡的形態及大膽的色調呈現。此外,克雷格﹣馬丁也是一位非常重要的藝術教育家,他影響了現在為大眾熟知的“青年英國藝術家一代(YBA)”的格雷·休莫(Gary Hume)、達米安·赫斯特(Damien Hirst)、莎拉·盧卡斯(Sarah Lucas)等著名藝術家。他在2000年被授銜大英帝國司令勛章(CBE),並於2006年當選皇家美術學會院士。克雷格﹣馬丁在不少英國及國際公共藝術項目中扮演了重要角色,譬如他參與策劃了的2015年皇家美術學會夏季展,也曾擔任約翰·摩爾藝術獎中國區(John Moores Painting Prize)的評委。

ART.ZIP: How was your trip to China?

MCM: It was very exciting. I had my exhibition of paintings first in Shanghai, and then recently in Wuhan. Wuhan particularly interested me, because I am 1/8 Chinese. My great grandmother was Chinese and when I was invited to go to Wuhan, I didn’t know anything about it, so I looked up the Wikipedia about Wuhan. I discovered that part of Wuhan used to be Hankou, and then I realised that my great grandmother came from Hankou. My grandmother and father were both born in Hankou. Of all the places in China, it is the most amazing place to have asked for my exhibition. I needed to go back where my family comes from!

ART.ZIP: Was that the reason why you had exhibition in Wuhan?

MCM: Not really. For many years I hoped to have an exhibition in China, because of my family connection. At the Hubei Museum in Wuhan they did not realize this relationship when they invited me. It was all by chance, an amazing coincidence—a very Chinese coincidence. Or destiny.

ART.ZIP: How did you prepare for the exhibition and how long did that take?

MCM: The director of the Himalayas Museum, Mr. Wong, and Marianne Holtermann, a British art consultant, came to visit me and invited me to present an exhibition. Firstly, I went to Shanghai to see the museum and the space, which are very big. It is difficult to decide what I should show and what I should send—it was such a long distance and such a big place. So I decided to make new paintings, rather than do something as retrospective. I wanted to make new works of very contemporary objects, which I thought was interesting because many of them are manufactured in China, but these objects are universal, they go across all languages, all cultures.

ART.ZIP: Yes, it is very interesting that there is an anthropological dimension in the everyday objects that you feature. They are culturally contingent but the globalisation really makes it possible for the objects to be recognised by Chinese people.

MCM: By everyone. There was something really wonderful about being able to feel confident about doing my first exhibition in China, that people would have no trouble recognising the images and understanding my work. I also have a lot of freedom in the way I use colour, and I think that kind of freedom in colour is also understandable in every culture.

ART.ZIP: The images, especially the iPhone painting, are tinged with irony and humour, because in China everyone is holding an iPhone and everyone desires for an iPhone. Also the way that you represent the object is very interesting: you put the object in the centre of the canvas, so that the image invokes a sense of portraiture. Could you tell us a bit more about the politics of your representation, if there is any?

MCM: I am trying to present objects in the simplest way possible, and I don’t want to supply too much context. All the basic information should be in the object itself. The viewer brings all additional information to the image. Many of these objects are mass manufactured. They are essentially impersonal, but if you own one, it’s very personal. The identifying personal association with these objects, which are not personal, is an important modern experience—our real association, the strands of our feelings about the objects that surround us. It’s also because they are so familiar, we don’t think of them as important in the world, but actually they are the world. We are living in a very material world.

ART.ZIP: Are you commenting on the current state of the consumer society or consumerism?

MCM: Not particularly, though I see that as a possibility for others, but don’t want people to see it as a specific intention on my part. If somebody has that interest in these objects, of course they can see that, but from my own point of view, I’d rather stay as neutral as possible.

ART.ZIP: What do you think of cultural exchange between the UK and China?

MCM: I think that the exchange is very important. Before I did the exhibition in Shanghai, I was a judge for the John Moores Painting Prize and that was very interesting for me, because some of the judges are Chinese and some are British, and we look at the work together. It was fascinating that most of the time we were in complete agreement, but some of the time we were not. People send their works from all over China. For a foreigner, this gave me a very good picture about what is happening in China and its art today. It was very special when we looked at 3000 paintings, as most of the paintings were not from well-known artists, but were from people who are not famous in China. The prizewinners have the opportunities to travel to England and meet new people. This is what really cultural exchange should be.

ART.ZIP: There are people commenting that some of the art is quite ‘British’, do you think if there is a ‘Britishness’ in art, or if there is any common character shared by British artists?

MCM: I don’t really think so except in a very general sense. I think that cultural influence is very deep, it is not on the surface and this is true in every culture. For example, in England, we teach about Expressionism, but it is not the same in England as it is in Germany, because Expressionism is more important in the history of German art. So although it is the same history, the emphasis is different. It’s just that some things more important for this and less important for that, and this is true regardless the style of the art. Sometimes we look at a work of art and we immediately think that it is German art, but with some we don’t, it’s not so obvious. I don’t like the idea of nationalism, but on the other hand, I do see that there is a difference between British art, German art and Chinese art. This is because of the history, because each country has different history and each country reads and teaches that history differently.

ART.ZIP: The point of pedagogy is interesting. We know that you were trained under the pedagogy of Josef Albers at the Yale University, and you practiced in teaching at the Goldsmiths. Does the way that you were trained affect the way you teach?

MCM: Although I greatly admired him as a teacher I didn’t teach the same way as Josef Albers at all. In a sense Albers was an authoritarian teacher. He had rules about most things and very definite ideas. When I started teaching in the late 60s, in a time of student revolutions and changes, they changed in question of society and authority. In Britain the power of authority was weakened. There was much more individual freedom and there was great academic freedom. If you were really interested in being creative in teaching, it was possible to try new methods and that was really what we did in Goldsmiths—we used the freedom of the time. Today, in British education, we don’t have that kind of freedom. Now there are many regulations, many rules, and bureaucracies in the education system. So, it doesn’t have the flexibility that it had in the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s. This was a period that has the most flexibility in education. When I was in Wuhan, I went to the art school, which was one of the most important art schools in China, an enormous art school. One of the things that I saw is that the schools are very big and there are so many students. It is very difficult to me to teach creative activity to great numbers of people, because I think you need personal contact with students, you need to speak individually, you need individual contact between teachers and students, you need continuity. To me this is a problem in mass education in every society now. In the period of ‘60s to the ‘90s, British art schools were small, and the number of student was small. The personal contact was great.

ART.ZIP: The colour in your work is very stimulating. The colour is often suggestive of the nature of the object, or the psychic effect that the object has on human life. Could you speak a bit more about your conception on using the colour and what goal you want to achieve through it?

MCM: In my early work I didn’t use much colour. I had no confidence about how I could do this. I had been doing wall drawings, but they were always black and white. Then in 1993 I painted all the walls of a room to make an installation and as soon as I saw the colour on the walls, it changed my whole life. Usually people start with painting and then go on to make installations; my painting came from installation. In the studio, it took me a long time to work out how to make paintings that had the intensity that I was able to create by painting whole rooms. There is a very limited number of colours but there are many variations. I decided to use the purest palette that I could. So that’s how I started with the colours. When I look at the objects that I draw, it seems to me so obvious about the contemporary world—these are our world. I decided I should use the most obvious colours – the basic colours with simple names: red, purple, yellow, pink. I don’t distort the objects, I don’t change the objects, I draw them exactly as they are. I do the opposite with the colours.

In the Summer Exhibition at the academy this year, I used the colours for the exhibition that I know from my work. When I told people that I was going to paint the big room magenta, many people thought that I was crazy. It was so dangerous because the other artists might be very unhappy, but once the exhibition took place, it was obvious that the wall colour made the work look better not worse and created a memorable room! The first exhibition that I used bright colours in painting the room was at a gallery in Paris, and there were seven rooms in the gallery. It was very nice gallery, not very big rooms, around the courtyard, it was a very French space. So I painted each room in different colour. When people came to the exhibition, I saw they came with a smile. Everybody smiles— this is something I never saw in my work before.

The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition is very difficult to hang because it is so large and the quality is very varied. There are 1,200 works, an almost impossible number, some are interesting and some are not. Usually when I go to the Summer Exhibition, I think every room is too much the same, and I loose my capacity to look at individual works. So I tried to make each room feel more individual and playful. I tried to play things against each other: big and small, abstract and figurative, painting and sculpture.

When I was teaching I often said to students that you are trying to be too creative, don’t be too creative, because there is so much already in what you are making, you don’t need to do very much. You just need to do a little bit, and that is a lot. It’s always more than you think. You can see in my paintings, I’ve taken away the context, I’ve taken away the shadows, I’ve taken away expression, I’ve taken away the personal, and yet so much remains! I’ve taken away everything I could think of, and yet what remains is enough. These days many more people come to my work, and once they see my work they will always recognize it.

ART.ZIP: We know that you are interested in curating. Could you tell us a bit more about your curatorial idea?

MCM: I look at the character of the exhibition and I treat it as I would a painting or an installation. When I did the Summer Exhibition at Royal Academy, I did it exactly as I would when making a new work. A giant collage with many complicated pieces—this is because I’m trying to find a certain kind of unity and clarity. Usually they put all the largest pictures in one room, the largest room, but it’s hard to look at so many big pictures together – they fight for attention. However, if you mix big pictures with little pictures, and you put big pictures in other rooms, it makes each room much stronger – the big pictures and tiny pictures in the same room. This is why the exhibition looks so different this year. My idea for every exhibition is we should be able to see every individual work without being distracted by the others, and it doesn’t matter if it’s quite crowded. For instance, I would never put a sculpture in front of a painting, so that it is difficult to see the painting. I always place each thing so you can see it isolated. You can focus on every individual work. It’s important for me to give each thing the possibility to speak and also to allow artworks speak to each other. So if things are too similar, the dialogue is not very interesting. If you put in contrast, big and small, abstract and representational, you set up the possibility of a discourse. At the Summer Exhibition, I didn’t really change anything; it’s the same exhibition. All I changed is the presentation. I didn’t really change the rules. People say there aren’t so many works this year, but its only 50 less works than usual. It just looks like less, because it is more structured.

ART.ZIP: There are quite a few Chinese artists who are informed by the visual language of pop art and develop the so-called ‘political pop’. Some critics such as David Joselit suggested that they are speaking in Western language to tell Chinese story, which is more easily recognisable and acknowledged by the Western audience and institutions. What do you think of this phenomenon?

MCM: There is no doubt when one comes from the West to China one understands pop art as having originally developed as part of Western tradition. There is a historical development, in which things find resonance in different places. When I go to China I see many artists whose work reflects on aspects of contemporary popular culture but obviously the history of Western art is not part of their own tradition. I think it is problematic for a person who doesn’t know how it is related. I think from an artist’s point of view, everything in art, in fact everything in the world is available as material. As an artist you are free to use any image, any style, any idea from any culture and any period of history. I think the best approach is not to be too much like the thing that they are referring to, see it as a guide. If you try to copy something exactly you won’t get it correct, because you don’t share the same tradition and context. You can take things from the past, from the culture, from the immediate past and things that have not yet entered the culture, so they have no history yet. You can create your own context.

Often people do not properly value things that they are good at naturally because they find them too easy. That is very problematic. If I did not love the things that I do, how could I spend my life doing this? You have to invest what you spend your life doing with pleasure. It is very important to develop the thing that you are naturally good at, that you are truly interested in. You can’t force yourself to be something you are not. When I was a very young student I loved and admired the work of Sam Beckett, who is famously pessimistic, and whose writing is an extraordinary examination of emptiness. I wanted to be like Beckett. I don’t have the same attitude toward the world, I’m naturally optimistic, and so of course I could never be like Beckett. You can’t force yourself to become like someone you admire. The person you admire was true to himself. You can only truly honour him by being true to yourself. You can’t honour someone by copying them or trying to be exactly like them. If you close the door to the things you feel comfortable with, you will never discover the truth about yourself.

ART.ZIP: 克雷格﹣馬丁先生您好,請您介紹一下這次中國的巡展情況吧。

MCM: 這是一次非常令人激動的經歷。我先後在上海和武漢舉辦了個人展覽。武漢對我而言是一個特別有意思的地方,因為我有八分之一的中國血統,我的曾祖母是中國人,在我受邀去武漢之前,我對那裡完全不了解,所以我專門去上網查關於武漢的介紹。我發現原來漢口是武漢的一部分,然後意識到我的曾祖母就是漢口人。我的曾祖母和父親都在漢口出生。漢口在邀請我舉辦個展的中國城市中是一個非常神奇的地方,我想我應該回到我家人出生的地方去看看。

ART.ZIP: 這正是您選擇在武漢舉辦個人展覽的原因嗎?

MCM: 也不完全,其實多年來我一直有在故鄉舉辦個展的心願。湖北美術館邀請我的時候並不知道我與武漢這個城市的關係。只能說這是一個非常偶然的巧合,一個神奇的巧合——很中國式的巧合。或说是命運。

ART.ZIP: 您為這次展覽做了哪些準備?您花了多長時間來布展?

MCM: 上海喜馬拉雅美術館的王館長和英國藝術顧問瑪麗安·霍特曼(Marianne Holtermann)邀請我來舉辦這次展覽。我先去到上海考察美術館的展覽場地。那個美術館很大,讓人很難決定該以怎樣的方式去填充這麼大的一個空間,所以我決定用新作品來布展,用非常當代的新作品來表現非常當代的事物。我認為這樣的呈現方式會非常有趣,因為這些物品的都是中國制造的,而且我認為這些物品是具有普世意義、是超越語言、超越文化界限的。

ART.ZIP: 是的,您從人類學的視角來表現日常生活中的常見事物這點特別有趣。它們因文化差異而不同,但如今全球化影響下使得這些差異性變得模糊,中國的觀眾也能夠辨識出它們是什麼。

MCM: 是的,它們可以為所有人所認識。我有足夠的信心在中國舉辦我的首次個展,中國觀眾對於我的繪畫作品不會有理解困難。我繪畫作品中的色彩運用非常自由,色彩的自由在任何文化中都是可以接受的。

ART.ZIP: 那些圖片,特別是蘋果手機的畫作,充滿了諷刺和幽默,在中國幾乎每個人都擁有一部蘋果手機。您的表達方式也非常有趣:您把手機放在了畫布中央,讓整個畫面表現出一種肖像畫的感覺。您可以稍微介紹一下這個作品中所要表達的含義嗎?

MCM: 我嘗試用最簡單的形式去呈現物品,我並不希望去傳達過多的信息,所有的基本信息其實已經都涵蓋於作品本身。觀看者把所有的其他信息附加在這些圖片上。這些產品中的大部分是大規模生產的產品,其本身不具備任何個性,但是如果你擁有並開始使用它們,它們就會變得個人化──物品和人緊密的聯繫起來,這是一個非常重要的現代理念,我們的個人習慣、個人感受全部傾注在我們攜帶的物品上。這些物品因為看似太過相同,所以往往為我們所忽略,但是它們在當下的物質社會中是非常重要的組成部分。

ART.ZIP: 您是在批評現代社會的消費主義觀念嗎?

MCM: 並不是的,不過我知道有些人會這樣看我的作品,但是不希望看到人們把注意力放在這些部分,這是仁者見仁智者見智的。從他們的角度來看,我的作品確實具有這種批判性,但是對我而言,我不願意過多地去解讀我的作品。

ART.ZIP: 您怎樣看待中英之間的文化交流?

MCM: 文化交流非常重要。在我的上海巡展前,我擔任了約翰·摩爾藝術獎(John Moores Prize)的評委,這項工作非常有趣,因為獎項的評委們分別來自中國和英國,我們在一起評判作品。我們對於作品的判斷雖然也會有一些分歧,大部分時候意見還是統一的。作為一個外國人我有機會作為一個評委來審視來自中國各地的藝術家作品,這讓我對中國當代藝術的發展有了一定了解,這是非常有意義的文化交流。這些我們看到的藝術家並不出名,但通過這個平台獲獎的藝術家們能獲得去英國旅行的機會並結識其他藝術家,這就是文化交流的意義所在。

ART.ZIP: 有人認為一些特定的藝術表現很“英倫範”,那麼您認為存在這種“英國範兒”藝術嗎?英國藝術家的作品中是否確實具有一些共通的東西?

MCM: 一般意義而言,我並不同意這種看法。我認為文化對藝術的影響是深刻、無所不在的。舉個例子,在英國,我們的大學裡面也教授表現主義繪畫,但是在英國所教授的內容和德國是不同的,因為表現主義在德國藝術中占據了更為重要的地位,所以雖然是相同的藝術但教授的側重點卻不同。雖然各個國家的表現主義各有特色,但他們本質上是具有共性的。我們應該忽略一些文化的國別差異而更加關注藝術風格本身。我不贊成用“國家性”的概念來判斷藝術價值,雖然我們得承認英國藝術、德國藝術和中國藝術之間有一定的差異性。但是這些差別其實是各國家不同的歷史傳承方式造成的。

ART.ZIP: 教學這點特別有趣。我們知道您曾於耶魯大學師從於約瑟夫·阿伯斯(Josef Albers),您自己也曾當過老師,任教於金匠學院。您怎樣看待自己的教學方式?

MCM: 雖然我很欣賞約瑟夫·阿伯斯的教學,但是我的教育與他的完全不同。某種意義上而言,約瑟夫是一個非常強調權威性的老師。他對每件事都強調規則和定律。我從六十年代末開始任教,當時正值一系列英國學生運動,統治者的權威性遭到削弱。個人的自由越來越多,學校裡面擁有非常自由的學術環境。我們在金匠學院中做了許多教學創新。今天我們已經不可能給予學生當時那麼多自由的時間和空間。現在的英國教育有越來越多的限制和約束,已經沒有了六、七十乃至八十年代學生那樣自由的空氣。當我走進武漢的美術學院,我發現這所學院規模很大,學生很多。但對我而言很難為那樣多的學生做創意型教育,因為你需要與學生單獨接觸、溝通,需要老師與學生之間單獨的、持續的交流。在六十到九十年代,英國的藝術學校的規模還很小,有利於師生之間的溝通。

ART.ZIP: 您作品中的色彩非常引人注目,色彩在您作品中往往可以反映事物的本質和它們對人類精神世界與生活所帶來的影響。可以談談您在創作過程中運用色彩的理念和您希望達到的效果嗎?

MCM: 我的早期作品並未運用太多的色彩。我對自己運用色彩的能力沒有太多信心。所以當時我創作了大量的黑白色作品。直到1993年我在創作一個空間裝置作品,我把墻塗成了彩色,墻上的色彩啟發了我,改變了我後來的創作方式。通常的順序是藝術家先從事繪畫,然後制作裝置作品,而我是恰好相反,我繪畫的靈感來自於裝置。每當我走進工作室,我首先會花很多時間去思考我究竟要去創作怎樣的作品:墻上豐富的色彩驅使我創作更加色彩化的作品。我的重點是關注繪畫中的色彩,對於物品的選擇,我盡量選取生活中最為顯而易見的物件,同時也用最為簡約的顏色去創作,不混和顏料,只使用純色,我選用最普通的顏色:紅色、紫色、黃色、粉紅色,我不會去扭曲或者去改變一個物品,我要呈現的是一個物品的本貌。在今年的夏季展中,我為展覽設計的色彩靈感來自於我自己的作品。當我對人們說我希望在這個大展覽用什麼顏色呈現的時候,他們都以為我瘋了,因為這樣的設計會是非常冒險的。但是當展覽開幕之後,這些色彩與所有的參展作品非常好地融合在一起,令人印象深刻。在巴黎的展覽,我第一次用亮色去粉刷房間,那是一個非常棒的美術館:空間大小適中,周圍都是花園,非常法式。美術館一共有七間展廳,所以我用不同的顏色粉刷不同的展間,展覽的效果很棒,每個來觀看展覽的人笑了,我甚至在自己的作品展覽時也沒有見過那樣的笑容呢。

夏季展的策展非常難,因為展廳的空間非常大,作品的種類也非常多元化。因為一共有1200件參展作品,這對於一個展覽的作品量而言實在是一個非常龐大的數字。有些很有趣但是有一些也很乏味。每次我去看夏季展的時候,我覺得每個房間太過類似,這讓我無法專注地欣賞每件作品。我決定要讓每個房間更具有獨特性,更加有趣。我對於每個作品的擺放都經過深思熟慮,所以為了讓每個房間都有自己的獨特性,我需要去組織一個合理的擺放順序。

當我在大學任教時我常常會教育學生:你們都希望自己的作品非常有創意,但是不要過於尋求創新,因為物品本身有自己的特點,並不需要我們去改變太多。一點點改動就會看起來有相當大的改變。看看這些參展的畫作,除去所有的陰影、參展環境、個人化等因素,也仍然還是完整的作品。

ART.ZIP: 我們知道您對策展很有興趣,可以談談您的策展理念嗎?

MCM: 我關注展覽的個性特色,策展對我而言更像是創作一件繪畫或裝置作品。當我在皇家美術學會策劃夏季展覽的時候,我完全把策展的過程當作創作全新的作品。我希望在這個空間的展覽中呈現出內容不平凡的作品。皇家美術學會擁有可以容納上百件作品的巨大展覽空間,我需要更好地組織作品順序,讓參展的作品擺放看起來更有條理地呈現給觀眾,避免讓畫作在展覽的過程中互相打擾,展覽的時候相對地擁擠並不會影響展覽本身的質量。舉個例子,我不會把一個雕塑放在畫前面。我會盡量讓觀眾能夠有足夠的空間去仔細觀看每一件作品,讓觀眾之間可以去交流。如果畫太小,這樣的交流會變得非常無趣。但是如果把大畫和小畫、抽象畫和具象畫混搭在一起擺放,就會有趣得多。在這次夏季展中,我沒有作任何改變,只是改變了作品擺放順序,雖然人們議論說今年的作品較往年數量有所減少,但實際上也只比往年少了50件作品,看起來少的原因是畫作的擺放次序使然。

ART.ZIP: 很多中國藝術家受到波普藝術的影響,創造出所謂的“政治波普”藝術。評論家如大衛·喬斯利特(David Joselit)認為他們是用西方語言來述說中國內容,這樣可以更容易的為西方觀眾和機構所理解。您怎麼看待這個現象?

MCM: 西方人到中國會發現西方藝術傳統已經成為當今中國藝術不可缺少的一部分,波普藝術是源於西方的藝術傳統。這是一個歷史的演變過程。當我到中國看到藝術家們用西方波普繪畫思維表達他們本國文化的時候,很多人並不知道怎樣把兩種文化聯繫起來,我覺得如何可以將東西方文化完美的結合起來將會更有利於本國藝術的發展。從一個藝術家的角度來看,這個世界上的一切都是由物質組成的,你可以自由地運用任何文化中的任何元素來表達自己的藝術理念。中國藝術家應該以西方藝術作為一個參考,而不是完全的模仿,因為畢竟你們不具備西方的文化傳統和文化環境。你們可以結合自己傳統文化和近現代文化,來創造出屬於自己的當代藝術。

人們常常忽略自己擅長的事情,因為他們覺得這些事情對他們來說過於簡單。很多人覺得沈浸於自己喜歡的事物當中是一件非常罪惡的事情,這種想法是錯誤的,為什麼我要花費我寶貴的人生去做一件自己討厭的事情呢?人們應該去做自己愛做的事,應該去發展自己的興趣愛好而不是去逼迫自己做某些事。當我還是個年輕學生的時候我喜歡薩謬爾·貝克特(Samuel Beckett),貝克特是一位充滿悲觀和虛無主義的作家,我希望自己將來能像貝克特那樣,但是你們也知道,我的世界觀就是與他不一樣,我是一個樂觀的人,所以最後我也沒能變成貝克特。你不能去逼迫自己變成某種人,你應該去做你自己。你可以去欣賞別人但是沒有必要去做別人,這樣是違反自然法則的。如果你不做讓自己開心的事情,那麼你永遠也發現不了人生的真諦。