Shoran Jiang on This Is Art, Art Education, and Cross-Cultural Creativity

姜嘯然談《這才是藝術》再版、藝術啓蒙與跨文化創作

Early autumn in London. The sky stretches wide and clear, not a cloud in sight. Leaves drift and twirl gently as they fall, like a painting slowly unrolling, each stroke tracing the quiet passage of time. On such a tranquil afternoon, we sat down with Shoran Jiang (Jiang Xiaoran) to talk about This Is Art, a tender, thoughtful series on artistic awakening that moves softly between parent and child, unfolding through stories and brushstrokes.

In her calm yet steady voice, drawing is no longer defined by technique alone. Technique, in her view, is a tool that serves expression, not an end in itself. Art education, therefore, is not about instructing children what to draw, but about giving them the freedom to feel, imagine, and express.

She said, “I had never seen books like this when I was young.” So, she wrote one for her own children, and also for the girl she once was: a child who grew up in studios and classrooms, always longing for a book that could speak not only of art, but of people, their stories, their emotions, their lives. This book began as a mother’s quiet attempt to build a bridge, for her children growing up far from home. And where it arrives is like a gentle letter, folded back across time: a message to her younger self, and to every child still finding their way through the world.

When she speaks about the classroom, she often returns to a simple belief: Let children feel first. Then talk about knowledge. That’s why she rarely demonstrates finished works in class. She worries that once she picks up a brush, the children’s eyes will fix on her example, and their own possibilities will quietly close off. Instead, she breaks a cat down into shapes and blocks of color, turning the anxiety of “I don’t know how to draw” into something approachable and solvable. She introduces a “No Black Challenge”, banning black outlines altogether, helping children break free from the habitual formula of contouring and colouring in. At the end of each session, she invites students to respond to one another’s work, but with one rule: they may speak only of what is good. In this way, every child is encouraged to grow from places of light. As for the adult obsession with “Does it look real?”, she smiles and says “Whether it looks real or not, it’s mostly a standard imposed by adults.”

Jiang moves through cultures like a nomadic artist, tracing her path between geographies. She was raised in China, with traditional roots, and later lived abroad, gathering new materials for expression: silk and ink, traditional clothing and contemporary symbols, placed side by side. The media has described her work as “Chinese backbone with European flair.” She has, in a sense, a painter’s palate attuned to memory, a taste for home that only the brush can reach: the gesture of folding dumplings, the flavour of lamb skewers, Chinese toon with eggs, and a quiet corner of her hometown. “The stomach is a GPS,” she jokes. Science, she notes, has even suggested that homesickness is just the memory of your gut microbiome, calling you back to where it first began. Life abroad gives her freedom to move between cultures, not as a place of loss, but as a fertile ground where language and image can take root. Her unique artistic style grows from precisely this in-between space. To not fully belong anywhere, perhaps, is a gift in itself.

As she writes in her book, “Drawing is not just a skill, but a way of thinking, a way to place your emotions.” And in her own work, she gently places the many pieces of her identity, again and again, through each mark on the page. When her children were small, her creative time was broken into fragments. She would wait until they went to bed by 7:30pm, then work from 8 until midnight. That narrow stretch of time belonged entirely to her, brief, hard-won, and deeply precious. It wasn’t until they entered secondary school that daytime hours returned to her—a sense of time once lost, now quietly restored. She often calls herself a “full-time mum, part-time artist.” But in her voice, there’s a steady, grounded strength. “If I were to imagine this stage of my life as a painting,” she says, “It feels like the storm has just passed. There’s still a trace of it lingering in the air, but the sky has cleared. And here I am, rolling up my sleeves and ready to begin again.”

We often ask women how they “balance” work and family, but that question itself is flawed. It rests on a structural bias that quietly assumes women must carry the burden of balance alone. Yet not speaking of it doesn’t make it disappear. The tension of inequality still exists. To become a mother is often to divide your time between love and responsibility. Creative work is interrupted and plans are postponed. These are the realities that shape a woman’s days. The so-called “cost” is not some grand tragedy, but something tucked inside each fragmented night and every small, rushed decision. Jiang reminds us that the scarcity of women artists who managed to create while also mothering is not a historical accident—it is a footnote made heavy by reality. But perhaps, when we acknowledge this truth gently, when we face it without shame, and speak of it without hesitation, that is where change begins.

From the pages of her book to the classroom, from the warmth of home to distant places, she paints a personal canvas across the many folds of her identity. This conversation is not just about This Is Art, it’s about This Is Life. Now, through the questions and the answers, let us step into her world, and read the art and life she’s made, one brushstroke at a time.

倫敦的初秋,天空清澈無雲,落葉輕旋而下,彷彿一幅緩緩鋪開的畫作,一筆一畫勾勒出時間靜靜流轉的輪廓。就在這樣一個恬淡的午後,我們與姜嘯然相見,談起那套在親子之間低聲流動、在故事與畫筆下徐徐展開的藝術啓蒙書——《這才是藝術》。

在她溫和堅定的語調中,繪畫不再只是技法的傳授,而是一種觀看世界與自我表達的方式;藝術教育,不是「教」什麼,而是給予孩子們自由感受與表達的空間。

她說,「我小時候沒有這樣的書。」於是,她寫了下來,寫給自己的孩子,也寫給那個曾在畫室和課堂中長大,卻始終渴望一套「講述藝術、講述人的故事」的書的自己。這套書的起點,源自一位母親想為成長在異國的孩子搭起一座橋;而它的落點,是一封溫柔的回信,寫給童年的自己,也寫給每一個正在成長的孩子。

談到課堂時,她常常回到一個樸素的堅持:先讓孩子感受,再去談知識。所以她很少在課上示範成品,怕自己一提筆,孩子們一眼就被定住。她會把一隻貓拆解成不同的形狀與色塊,讓「不會畫」的難題變得迎刃可解;她定下「No Black Challenge」,不許用黑色描邊,讓孩子們擺脫「勾邊+填色」的慣性;在課程尾聲,她要求大家互評,但只能說「好」的部分,讓每個孩子都能從光亮處生長。至於成年人那份最執念的評價——「像不像」,她笑著說:「像與不像,其實多半是大人在決定的。」

而她自己,像一位在文化地理之間穿行的遊牧者。成長的底色來自中國,異國生活的經歷,給了她更豐盈的表達手法:絹與墨、傳統服飾與當代意象並置,媒體稱她的風格為「漢骨歐風」。她擁有獨特的繪畫「味蕾」,那裡是只有畫筆才能抵達的原鄉:包子、羊肉串、香椿、包餃子的手勢,以及家鄉的一隅風景。「胃是GPS」,她打趣說,科學家把鄉愁解釋為腸道菌群的記憶。身處異國,給了她常常行走在兩種文化之間里的自由。但那並不是失落之地,而是一片可以滋養語言與圖像的土壤,她創作的獨特風格正從這裡生長出來。不完全屬於任何一邊,也未嘗不是一種饋贈。

就像她書里說的,「畫畫不只是技能,而是一種思考方式,一種安放情緒的方式」,而她自己,也在一次次落筆之間,安頓著自己的多重身份。孩子們還小時,她把創作時間切割成碎片——等他們在晚上七點半睡下後,從八點一直忙到午夜,那才是只屬於她自己的寶貴時光。直到孩子們上了中學,白天的時間「失而復得」。她戲稱自己是「full-time mum, part-time artist(全職媽媽,兼職藝術家)」,語氣里卻有一種安靜的堅定:「如果把現在這個階段的自己想象成一幅畫,應該是寫實而平靜的——像暴風雨剛過去,空氣里還帶著余韻,但天已經放晴了。我正想擼起袖子,再干點什麼。」

當我們問一位女性「如何平衡事業與家庭」,其實這是一個愚蠢且不公的問題。它背後隱含著一種結構性歧視,預設女性必須獨自承擔所謂「平衡」的義務。但這種歧視並不會因為回避而消失。性別不平等的張力始終存在,成為母親往往意味著要在愛與責任之間不斷分配時間:創作被打斷,計劃被推遲,這些才是最真實的日常。所謂代價,並不是宏大的命題,而是潛藏在每一個被切碎的夜晚和每一次匆忙的取捨里。姜嘯然在談話中提到,縱觀藝術史,能夠同時兼顧創作與母職的女藝術家寥寥無幾,這並非偶然,而是現實的沉重注腳。而當我們溫柔地承認它,坦然地直面它,不再失語,也許正是改變的開端。

從書頁到課堂,從家庭到遠方,她在多重身份的縫隙中描摹出屬於自己的畫卷。這場對談,不止講述「這才是藝術」,更是照見「這才是生活」。接下來,就讓我們在問與答之間,共同閱讀她的藝術與人生。

From the Reprint of This Is Art

從《這才是藝術》再版談起

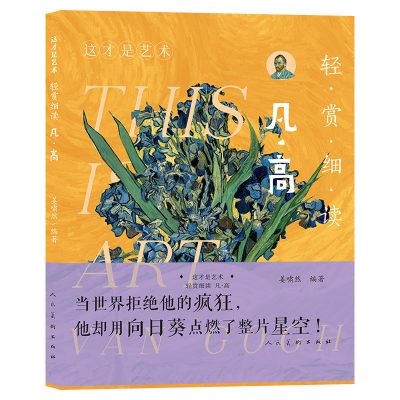

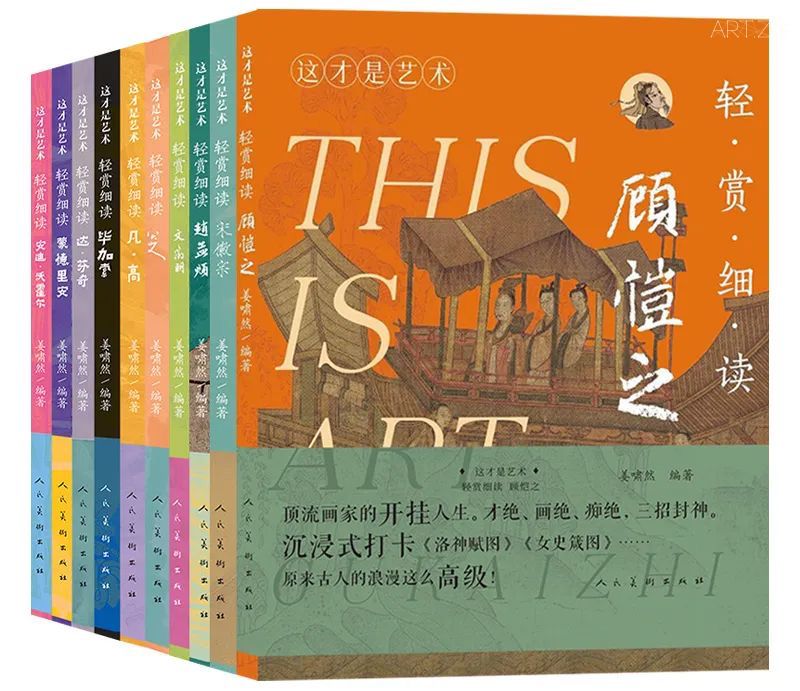

AZ: First of all, congratulations on the reprint of your book series This Is Art. With this new edition, were there any changes made to the content?

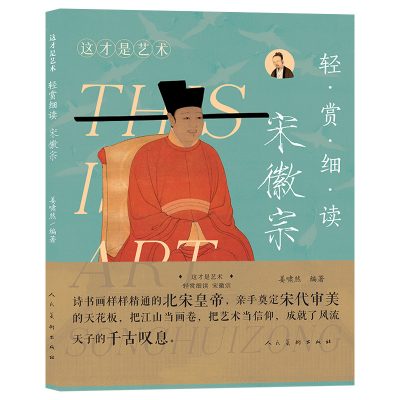

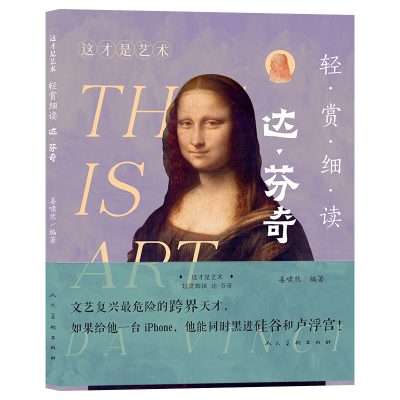

SJ: The main focus of this reprint was to refine the overall presentation and enhance the reading experience. There weren’t many changes to the written content, but we made several updates to the design. The cover has been completely redesigned, and we also reworked the spine band. On the back, instead of traditional blurbs, we now use excerpt-style copywriting, which gives the book a more cohesive and distinctive look. We also added small portraits of the featured artists. On the front cover, we included four Chinese characters 「輕·賞·細·讀」to evoke a slower, more mindful reading atmosphere. I hope that when the book is displayed in stores, it can immediately catch the reader’s eye and reach a wider audience.

AZ: I remember your talk during the London Book Fair, you mentioned that “introducing children to art across Eastern and Western cultures can begin by telling stories—about people, not just paintings”. You said helping children understand art in a lively, engaging way is more important than simply delivering knowledge. So when you first started writing This Is Art, what sparked the idea? Was it always intended as a book about art for children?

SJ: Honestly, it started quite simply, I just wanted to write something for my children. I felt that kids need art they can actually understand, not vague or lofty language. When I was at university, our professors often used terms like 「氣韻生動」(spirit resonance) or 「古法用筆」(classical brush techniques). It sounded profound, but most of us had no real clue what it meant. And if college students find it confusing, how can young children possibly get it? So I kept reminding myself: don’t complicate what should be simple.

From the very beginning, the language of this series was written with children in mind—clear, accessible, and story-driven. I hoped they would find it fun to read, and that through the stories they might slowly begin to feel the beauty of art. The publisher’s director once joked that he only knew of two people who started writing books just because they wanted to create something for their children, J.K. Rowling and me. I laughed, of course, it’s obviously an exaggeration, but it did touch on the truth. This really is a book written for children.

There was also a more personal reason. My children grew up in the UK, and Chinese hasn’t been easy for them. I wanted these books to be a way for them to experience not just the power of art, but also the beauty and playfulness of the Chinese language. The series feature both Chinese and Western artists, and through that contrast, I hoped they could see the many different forms of art, and also get a sense of what Chinese art looks like.

At the heart of it, I just want them to carry a sense of beauty with them as they grow. Life is long. To experience even a little beauty each day is already a kind of happiness.

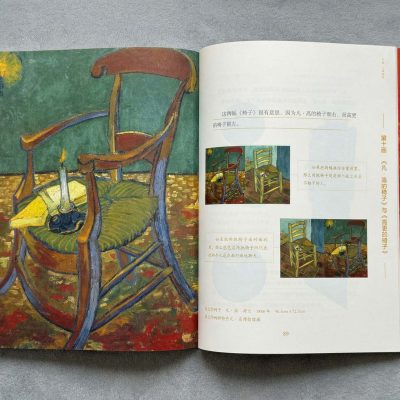

AZ: Each artist in the series feels like a small, self-contained stage, yet together they form a rhythmically cohesive whole. How did you choose them? Some artists, like Van Gogh, had very complex life stories. You even describe him as someone who struggle his whole life. Were you concerned that children might find those parts too heavy?

SJ: There wasn’t any complicated logic behind the selection. Mostly, I chose artists I personally like and feel familiar with, so that the writing feels more natural and less forced, which also helps make the stories more accessible for children. I also kept in mind that this is an introductory series, so I picked artists which children or their parents might already know, so the book wouldn’t feel too unfamiliar when they open it.

As for the heavier parts of their life stories, I don’t think that’s something to avoid. In any field, if you want to reach the top, it’s never easy. Turning passion into a profession almost always comes with pressure and pain. I actually think it’s important for children to understand early on that life isn’t always smooth, and that love and struggle can coexist. Van Gogh’s life was undoubtedly difficult, but that doesn’t mean he suffered while painting. In fact, creation may well have been his refuge, his form of healing, his window to place himself into the world.

AZ: Will the series continue? If so, who will you write about next?

SJ: Yes, definitely. In fact, four new volumes are already in progress: Wang Xizhi, Michelangelo, Qi Baishi, and Monet. Wang Xizhi allows us to introduce calligraphy into the series; Qi Baishi, you could say, is a kind of cultural “celebrity” in China; and Michelangelo and Monet are timeless classics who naturally resonate with readers. Of course, working with image copyrights and high-resolution materials is a time-consuming but essential part of the process. We’re also exploring possibilities for bringing the series to international markets.

AZ: You’ve studied with some renowned artists and received formal training in professional art programmes. Could you share a bit about your own early experiences with art?

SJ: I actually enjoyed drawing as a child. When my family moved house, my father kept some of my early drawings. I looked through them recently and thought, “These aren’t bad at all!” I remember making painted fan designs when I was about five, and even now, they still feel fun and full of character.

My father loved calligraphy and painting, and he knew many artists, so he often took me to visit them. I remember meeting Pu Zuo, the younger brother of Pu Yi, the last emperor of China. I met him when I was in middle school, he was already in his seventies or eighties by then. The people I encountered then were all much older, spoke slowly, with kind expressions and a certain depth of presence. I remember watching someone use a brush to paint elegant orchid leaves, so fluid and effortless. I looked simple, but when I tried it myself, I realised it wasn’t easy as it seems. That atmosphere left a deep impression on me. You could say it was a kind of quiet influence that stayed with me.

Of course, later on, when I started preparing for art school, I had to go through all the standard academic training, sketching, life drawing, all the exam-focused drills. That part wasn’t as enjoyable. But looking back, I feel very lucky. In those early years, I had teachers who weren’t rigid or controlling. They let me explore and gave me space. They never forced me to draw the way they thought I should draw, they took me out to see the world and helped me find my own path.

AZ: Do you feel that, in a way, writing this series is a dialogue with your childhood self?

SJ: Absolutely. I had never seen books like this when I was young. I still remember the first time I was truly moved by art, it was in elementary school, during a trip to a Rodin sculpture exhibition. It was organized by my father’s workplace, and I still remember how formal the occasion felt. As soon as I stepped into the gallery, I was stunned: “So sculpture can look like this?” That sense of shock is still vivid. It was the first time I realized that art could be such a powerful form of expression.

I remember how direct the impact of Rodin’s work was: some of the sculptures had muscles that were sharply defined, others had skin rendered so delicately, and then there were parts that were intentionally left rough—to leave room for imagination. At that time, I had never seen a formal sculpture exhibition before, so I didn’t have any comparisons to make. I just remember The Thinker left a deep impression on me.

No one explained anything to me back then. No one told me what the works meant. I simply looked, relying on my own eyes and feelings. So when I later wrote This Is Art, I often thought: how wonderful it would have been if a book like this had existed back then.

In a way, the series really is for the child I once was, as much as it is for the children reading it today.

AZ: 先要恭喜你這套系列叢書迎來了再版。這次再版有沒有在內容上做什麼調整呢?

SJ: 這次再版的重點,其實放在整體呈現與閱讀體驗的再梳理上。外在設計上做了不少更新:封面換了全新的設計,腰封也重新調整;背面從原本的推薦語,改成了引文式的文案,讓整體視覺更統一,也更有辨識度,並特別加上了藝術家的小頭像。封面上添了「輕·賞·細·讀」四個字,希望在書店陳列時,能在第一時間吸引讀者的目光,觸及更廣泛的閱讀群體。

AZ: 記得你在今年倫敦書展的分享會上提到過,「跨越中西文化的兒童藝術啓蒙,其實可以從講人、講故事開始。」你當時說,讓孩子生動有趣地理解藝術,比灌輸知識更重要。那麼,當初寫《這才是藝術》這套書時,最初的契機是什麼?它一開始就是設定為「給孩子講藝術」嗎?

SJ:

最開始其實很簡單,就是想給孩子們寫。我覺得小朋友需要的是「能聽懂」的藝術,而不是那些雲里霧裡的說法。大學時常聽老師說「氣韻生動」「古法用筆」,聽著高深,但學生往往一頭霧水。小朋友更不可能理解,所以我一直提醒自己:要把複雜的講簡單。

所以這套書一開始的語言就是寫給小朋友的,深入淺出,希望他們讀的時候能覺得有趣,也能在故事里慢慢感受到藝術的美好。出版社社長還打趣說,他只知道兩個人是因為想給孩子寫書才動筆的,一個是JK羅琳,一個是我(笑)。雖然誇張,但確實點中了出發點——這就是一本寫給孩子的書。

寫這套書其實還有另一個私人原因是,我的孩子在英國長大,中文對他們來說不算輕鬆。我希望他們在讀的過程中,不僅能感受到藝術的魅力,也能體會到中文的趣味。書里既寫了中國藝術家,也寫了西方藝術家,我希望他們通過這種對照,看到藝術的多樣,也看到「中國的藝術」。說到底,就是希望他們在以後的人生里能多感受到一些美好。每天能遇見一點點美,就是一種幸福。

AZ: 這套書里每位藝術家都像一個獨立的小劇場,但合在一起又很有節奏感。你當時是怎麼挑選他們的?有些藝術家的人生軌跡很複雜,例如梵高,你還用了「一生不得志」這樣的詞,你會擔心孩子們消化不了嗎?

SJ: 其實沒有特別複雜的邏輯,主要是我自己比較喜歡、也比較瞭解的藝術家。這樣寫起來不會太生硬,也能更自然地介紹給孩子。另一方面也考慮到這套書是入門讀物,所以就挑選了一些辨識度高、大家耳熟能詳的人物,讓孩子和家長翻開時不會覺得陌生。

至於人生經歷的沉重一面,我覺得也沒關係。因為不管在哪個行業,如果想做到頂尖,它都不會是一件輕鬆的事。把興趣變成職業,必然伴隨壓力和痛苦,我反而覺得孩子應該早點明白:人生沒有一帆風順,熱愛和痛苦是可以並存的。梵高的生活確實很苦,但他在創作時未必是痛苦的,那反而是他的出口和療癒,是安放自己的那扇窗。

AZ: 這個系列還會繼續嗎?如果會,那麼接下來的會寫誰呢?

SJ: 會的。其實接下來新的四本已經在推進了:王羲之、米開朗基羅、齊白石和莫奈。王羲之可以把書法引入這個系列裡;齊白石,可以說是中國的「流量」;米開朗基羅和莫奈既是經典,也很容易引起大家的共鳴。圖片版權和高清版本的協調是比較繁瑣但很重要的工作,我們也在探索把這套書帶到海外市場的可能。

AZ: 你曾經師從過不少藝術名家,也在專業體系中接受過系統的訓練。你能分享一下小時候的藝術啟蒙嗎?

SJ: 我小時候其實挺喜歡畫畫的。我們家搬家的時候,我爸爸還留著我小時候畫的一些作品。我翻出來看,還覺得小時候畫得還挺好的。五歲的時候我就畫過一些扇面,現在看還是很有意思的。

我爸爸喜歡書畫,也認識一些藝術家,所以常常帶著我去見他們。比如溥佐(溥儀的弟弟),我中學時見到他,他已經七八十歲了。當時接觸的這些人都「特別年長」,說話很慢,神態和藹,身上帶著一種厚重感。看到毛筆很輕盈地在紙上畫出一條條蘭葉,看起來很容易,但是我自己試過,並不簡單。那種氛圍讓我印象很深,也算是一種耳濡目染。

當然,後來為了考學,還是要走素描、速寫那一套應試訓練,那部分就沒那麼開心了。但回頭看,我覺得自己很幸運——至少在最初的階段,我遇到的老師都不算刻板,保留了我對繪畫的興趣。他們帶我去看世界,給我很大的空間去發揮。他們都不是那種要求我按照他們的想法去畫畫的老師。

AZ: 那你會不會覺得,現在寫的這套書其實就是在和童年的自己對話?

SJ: 是的。我小時候真的沒有見過這樣的書。記得第一次真正被藝術震撼,是小學時去看羅丹的雕塑展。那是我爸爸單位組織的活動,大家一起坐車去,記憶里場面還挺隆重的。走進展廳,我整個人都愣住了——「原來雕塑可以做成這個樣子!」那種震撼直到現在都還很清晰。那是我第一次意識到,藝術可以這樣去表達。我記得羅丹的雕塑給我的直觀感受很強烈:有的作品肌肉線條非常清晰有力,細節分明;有的地方皮膚質感處理得十分細膩柔和;還有一些部分則刻意模糊,留出想像的空間。那時候我幾乎沒看過正式的雕塑展,所以談不上什麼比較,只是覺得《思想者》那件作品特別震撼。

不過當時並沒有人給我解釋什麼,也沒有人告訴我這些作品意味著什麼。我就是單純地看,靠自己的眼睛去感受。所以後來寫《這才是藝術》的時候,我常常想:如果當年有這樣的書,我會多幸福啊。某種意義上,這套書確實是寫給小時候的自己,也寫給現在的孩子們。

Art Education Everywhere: Home, Classroom, and the World Beyond

藝術教育無處不在:家庭、課堂與社會

AZ: You are not only an artist and creator, but also deeply involved in art education. How do you encourage creativity in your own children at home?

SJ: When they were younger, I used to ask them to draw something every day. We even have little portfolios at home, booklets full of their drawings. Back then it was easier to keep up with the routine. Back then it was easier to keep up with the routine. Now that they’re entering their teenage years, well, that’s a whole different story!

That said, I don’t interfere much. My two kids have very different personalities, and their drawings reflect that completely. My son tends to draw strong, three-dimensional forms, blocks and structures, perhaps influenced by the games he plays, while my daughters drawings tend to be softer, with more delicate lines and colours. I find these differences really fascinating. More than anything, I want them to grow into their own styles freely.

Once, I asked them both to draw a cat. That day, my son wasn’t in a good mood—his choice of colours, the shapes, even the expression on the cat’s face, all seemed to say “unhappy”. My daughter, by contrast, was in a good place that day; her lines were bright, lively, full of movement. Children express themselves very naturally through their drawings—you can see their emotions directly on the page. Sometimes, when they come home from school, I only need to look at their drawings to sense whether the day went smoothly or not.

I still remember once I asked them to draw a cat. On that day, my son was in a bad mood, his drawing was full of dark colours and angular shapes, and even the cat’s expression looked grumpy. My daughter, on the other hand, was in a good mood, and her lines and colours were extra bright and cheerful. You can see their emotions right there on the page. Sometimes when they come home from school, I just look at their drawings and immediately know how their days go.

There was one time my son even drew a picture of me—angry! In the drawing, I’m holding a ruler, and behind me are flashes of lightning. He said, “When you’re mad, it feels like lightning”. I was stunned! And I thought to myself, maybe I should try not to get so angry next time. (laughs)

Drawing really is a window. It gives kids a way to let out what they can’t easily put into words, and it gives parents a way to understand what’s going on inside.

AZ: Many parents worry about whether their child has “talent” or not. Some even see realism–how realistic it looks as the only standard. Your approach in the classroom seems quite different from traditional art training. How do you guide children in your teaching?

SJ: I think “looking realistic or not” is a standard imposed by adults. Most young children rarely think, “This doesn’t look right.” They usually feel quite confident about what they’ve drawn if you remove the pressure of comparison. So in my classes, I always emphasise: compare yourself to yourself, not to others. At the end of each session, we have a little peer review, but with a rule: everyone has to say something good about each other’s work, and about their own work too. This helps them notice their own strengths. Next time they draw, they remember, “This part was good, I can do more of that.” It’s a way to build confidence from inside out.

When I was young and learning calligraphy, one of my teachers had a big influence on me. Instead of constantly pointing out mistakes, he circled what we did well, marking it with a red circle. At the end of each class, we counted how many red circles we had received. That method really stuck with me, it taught us to focus on what we were doing right, rather than being constantly corrected. If a child only ever hears, “this is wrong” or “that’s not right’, they quickly lose the courage to even pick up a pen.

In my own classes, I also set a little rule called the “No Black Challenge”, which means no black outlines allowed. This encourages children to experiment: outlining with other colours, or using colour blocks directly. It helps open up their thinking. Another important rule is that I rarely draw alongside them. The moment I start drawing, they would stop exploring and start copying. I’d rather give them tools than answers. For example, I might suggest, “Break this down into shapes, what circles or triangles do you see?” Once they learn to deconstruct an image, they can figure it out on their own.

This method probably comes from my own background. I was trained in traditional Chinese ink painting, where structure is often built through line, while oil painting emphasises shapes and colour blocks. Both ways of thinking come naturally to me, so I try to pass that openness on to the kids.

I always tell my students: there is no single “right” way to draw. There’s no one path to expression. In my class, I want them to explore freely, even if it means drawing slowly. Some kids finish a piece in one session, some take two or three. I never rush them. Once children are rushed, they become anxious, and the work loses its balance. Different rhythms are not a problem, they are part of the creative process itself.

AZ: So what does technique mean in drawing? Do you think it ever conflicts with free expression?

SJ: To me, technique is a tool to support expression, but it is never the goal. If you have a complex image in your mind, technique helps you bring it onto the paper. But if there is only technique, without imagination or freedom, the work loses its vitality.

I learned sketching and life drawing when I was young, but that was purely exam-oriented—you learn whatever the test requires. That kind of learning didn’t bring much joy. In contrast, what I hope instead is that children can preserve their imagination in the early years, rather than being disciplined into rigid patterns.

Especially before the age of seven or eight, children’s creativity grows naturally. At that stage, they should be free to draw however they wish. Later on, when they begin to want to make things “look more realistic”, that’s the time to slowly introduce shape and technique. At that point, learning technique becomes their own choice, not something imposed on them.

AZ: Do you believe that aesthetic sense can be trained and developed? In your view, what lies at the heart of art and aesthetic education? And for everyday people or parents, how can they cultivate this in daily life?

SJ: Absolutely. Aesthetic sense is much like taste in food. If you regularly take children to eat delicious food, they naturally learn what “tastes good”. Art works the same way. If they are often exposed to great works, they gradually learn what “looks good”. It’s a habit, something that gets built over time.

To me, the core of aesthetic education is observation. David Hockney once said something which I totally agree, “Teaching drawing is teaching people to look.” Teaching art is really about teaching people how to see. Aesthetics isn’t just about what is “pretty”. Many works in contemporary art aren’t concerned with beauty in a conventional way, they might be ironic, critical, or confront deeply painful truths. But those honest, raw emotions , even when uncomfortable, can still be a form of beauty.

Many parents aren’t sure how to help their kids develop an eye for art. So they sign them up for classes that look neat and structured. But to me, aesthetic sense isn’t about knowing how to draw, or even having to step inside a museum. It’s about whether you can notice the small, meaningful moments in everyday life.

I personally like Hockney a lot. His use of colour appeals to children, partly because his work isn’t overly realistic. Children feel it’s close to them. If you show them a Renaissance masterpiece, they might think, ‘I could never draw like that’. But with Hockney, they often say, “I could try that.” That sense of closeness–that accessibility–is often the very door that opens them into the world of art.

AZ: 你不僅是一位藝術家與創作者,也持續積極地投入在藝術啓蒙教育中。你在家裡是怎么激发孩子的创作欲望的呢?

SJ: 孩子們還小的時候,我會要求他們每天畫點東西,家里还专门留着他们的作品集,一本本的都是他们的画作。那時候還能堅持,现在他们快要进入青春期了,就完全是另外一回事了。不過我平時干預得並不多。孩子們的性格不一樣,畫出來的東西也完全不同。兒子喜歡畫立體感很強的方塊,可能和他平時愛玩的遊戲有關;女兒則更偏向柔和、細膩的線條和色彩。這些差異我覺得特別有意思,我更希望他們自由地長出自己的樣子。

有一次我讓他們畫貓。那天兒子心情不太好,他畫的顏色、形狀,甚至連表情都寫滿了「不高興」;女兒那天狀態好,她畫出來的線條和色彩就格外明亮、活潑。其實每個孩子都能從自己的畫里表達想法,你能直接看到他們的情緒。有時候他們從學校回來,我一看他們的畫,就能猜到一天是不是過得不太順。

我還記得有一次,兒子畫了我生氣的樣子。畫里,我拿著戒尺,背景是一道道「閃電」。他說:「媽媽生氣的時候就是閃電的感覺。」我當時愣住了,心裡暗暗想:以後還是少生氣吧(笑)。畫畫真的是一個窗口,讓孩子把不開心的東西表達出來,也讓大人找到和他們溝通的方式。

AZ: 很多人會擔心「孩子到底有沒有天賦」,甚至把「畫得像不像」當作唯一的標準。你的課堂似乎和傳統的繪畫培訓班不太一樣,你會怎樣帶孩子們畫畫?

SJ: 我覺得「像不像」其實都是大人決定的,是大人加給孩子的標準。其實小朋友們自己不會覺得「我畫得不像」,他們常常覺得「畫得挺好」。如果不跟別人對比,他們是很自信的。所以在課堂上,我會特別強調:你要和自己比,不要和別人比。我還會在每節課結束時安排一個小小的互評環節,大家互相說彼此畫里的「好」,也說說自己畫得好的地方。這樣孩子們就會記得住自己的優點,下次畫畫時就知道「這裡好,我可以多畫一些」。這其實是在幫他們建立自信。

我自己小時候學書法,老師的做法對我很有啓發。他不會總是盯著你哪裡寫得不好,而是把寫得好的地方圈出來,用紅圈標注。每節課結束後,我們就數數自己得了多少個紅圈。這種方式讓我印象特別深刻:它讓孩子去關注自己的長處,而不是被不斷地挑錯。如果總是聽到「這裡不對、那裡不對」,孩子很容易就不敢動筆了。

我在課堂上還定了一個規則,叫「 No Black Challenge」——不許用黑色描邊。這樣他們就會嘗試用別的顏色勾線,或者直接用色塊表現,思維會更開放。還有一個原則是,我很少在課上親自畫,因為只要我一畫,孩子們就會照著我畫。我更願意給他們方法,而不是答案。比如我會提示:把複雜的東西拆開成幾個形狀,他們就能自己找到辦法。這個可能和我自己的背景有關。我學國畫時習慣用線條去建構畫面,而油畫強調的是色塊,這兩種思維方式對我來說都很自然。

所以我也會告訴孩子們:畫畫沒有唯一的標準答案,不同的路徑都可以通向表達。在我這兒,我更希望他們能自由探索。哪怕畫得慢一些也沒關係,有的孩子一節課就能完成,有的可能要兩三節,我都不會催。節奏的差異本身就是創作的一部分。

AZ: 那技法在繪畫里究竟意味著什麼?會不會和自由表達之間產生衝突?

SJ: 我覺得技法是一種幫助表達的工具,而不是目的本身。如果你腦海里有一個很複雜的畫面,技法能幫你順利地把它落到紙上。但如果只有技法,沒有想象力和自由,那畫出來的東西就會缺乏生命力。

我小時候也學過素描、速寫,但那主要是為了應付考試,就是「考什麼就學什麼」。那種學習方式並不會帶來多少快樂。相比之下,我更希望孩子們能在早期保有自己的想象力,而不是太早被規訓成一板一眼的樣子。

特別是在七八歲之前,孩子們的創造力是自然往上長的,這個階段就應該讓他們盡情地畫、自由地畫。等到他們自己開始產生「我想畫得像」的想法時,再慢慢帶他們進入造型與技法的訓練,那會是一個更自然的過程。那時候的技法學習就不再是被動的要求,而是主動的選擇。

AZ: 你認同審美是可以鍛鍊和培養的嗎?

在你看來,繪畫和審美教育的核心是什麼?普通人或者家長,又該怎樣在生活中去練習和培養這種能力?

SJ: 當然可以。審美其實跟吃飯一樣,你經常帶孩子吃好吃的,他自然就知道什麼是「好吃」;藝術也是一樣,你經常帶他們看好作品,他們自然就會知道什麼是「好」。這就是一個習慣養成的過程。

我覺得審美教育的核心其實在於培養觀察力。David Hockney說過,「Teaching drawing is teaching people to look(教畫畫就是教人去看)。」審美不只是看「漂亮」的東西。當代藝術里很多作品並不是為了追求美,它可能是在諷刺、批判,甚至是非常殘酷的真實。但即時是這樣的真實情感,也可以成為一種美的表達。

很多家長可能也不知道怎麼帶孩子去練習審美,所以就會去報一些看起來很「整齊」的培訓班。但在我看來,審美並不是非要會畫畫、或非得走進美術館,而是你能不能在生活里發現值得捕捉的瞬間。

我挺喜歡 Hockney 的,他用色大膽,小朋友也很喜歡。因為他不是那種特別寫實的畫風,所以孩子會覺得「離自己不遠」。你給孩子們看文藝復興時期的大師作品,他們會覺得「我畫不出來」;但看 Hockney,他們反而會說:「這個我也能畫!」這種親近感,才是孩子們願意進入藝術的第一個入口。

Portrait of Shoran Jiang (Jiang Xiaoran)

An Artist’s Inner Practice: Creation, Identity, and Expression

藝術家的自我修行:創作、身份與表達

AZ: What is your usual creative state like? What does painting mean to you?

SJ: For me, drawing is a form of healing. When I’m feeling restless or agitated, I often reach for something that doesn’t require much thought—quick sketches or spontaneous little drawings. It’s a way to quiet the noise. Back when my child was still small, I used to carry a sketchbook with me wherever I went. I’d draw as I walked, capturing passing moments. Now there’s a stack of those sketchbooks at home—none of them are completely filled. But that, in a way, is the point. Like an eraser that’s never quite used up, these sketchbooks carry fragments of time, never polished to an end.

Of course, when it comes to serious work, I shift into a more deliberate mode. Right now, I’m preparing for an exhibition in Shanghai, and there are still a few pieces left to finish. I make a list, check off each one. It’s methodical, almost pragmatic. And yet—when a piece is finally done, the joy is unmistakable. It feels like a quiet kind of triumph.

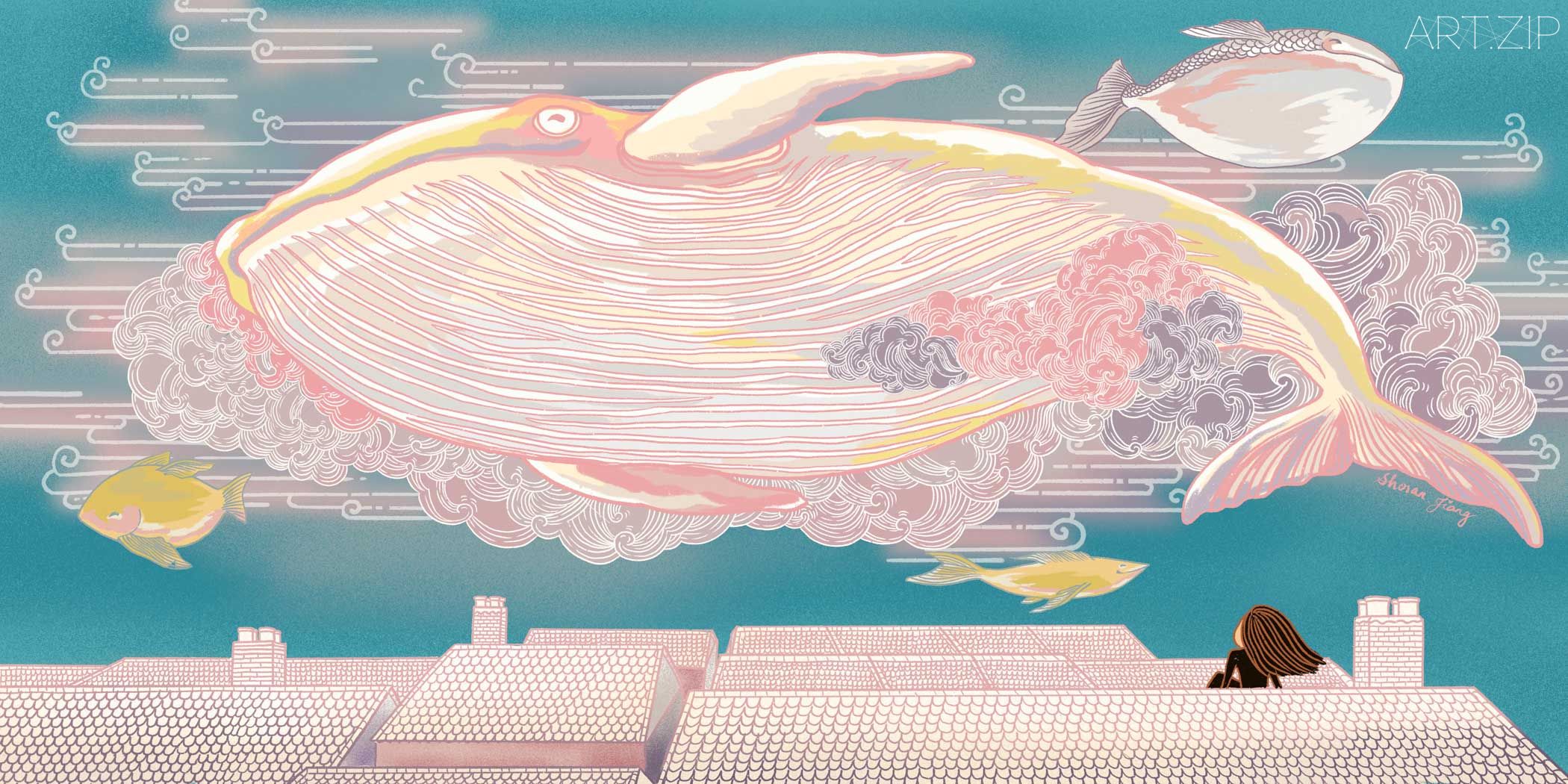

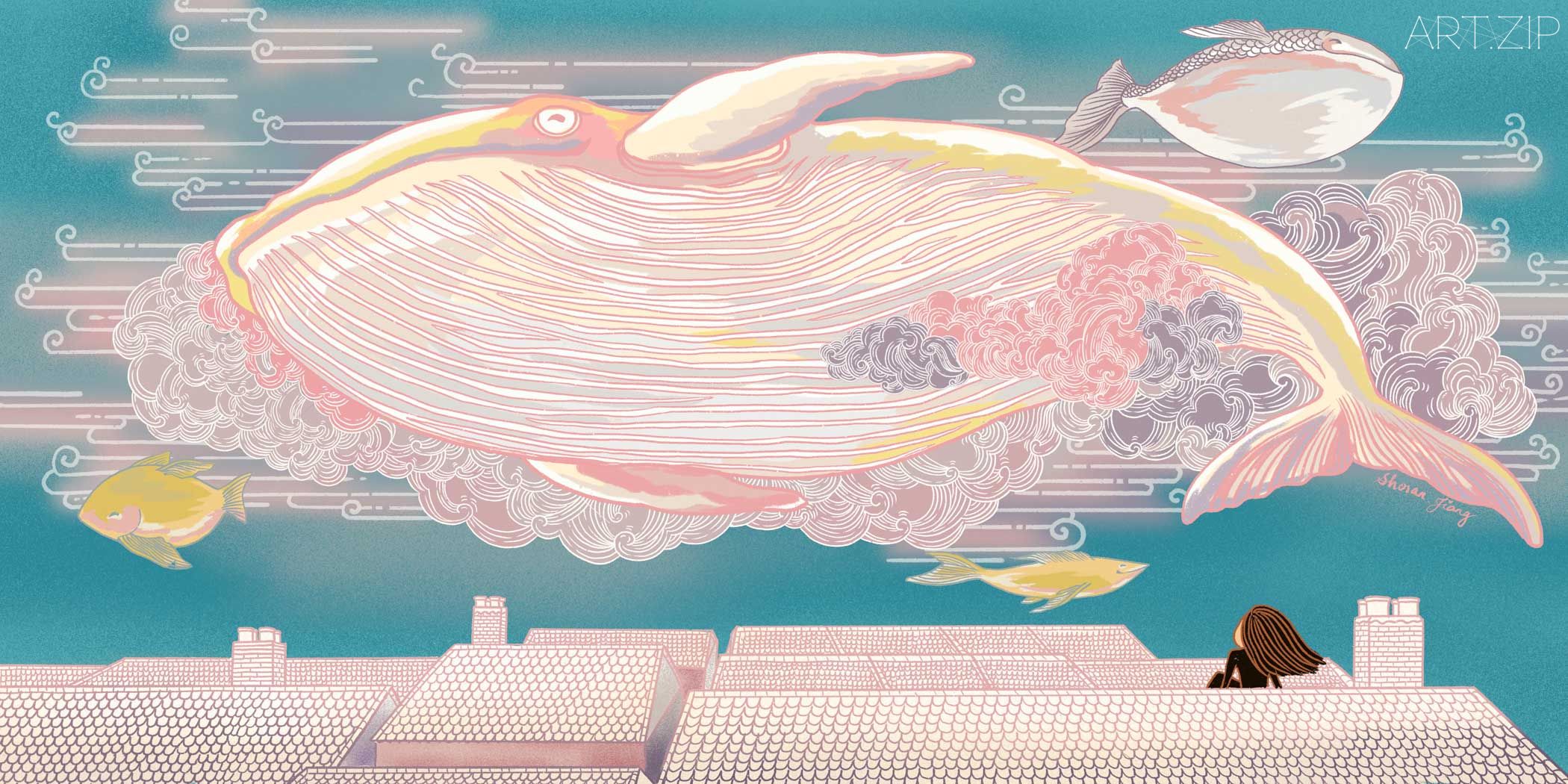

I’ve also explored working in series, like my Dreamscapes collection. In those, I painted visions pulled from my sleep: I once dreamt I was riding a dragon, soaring above my university campus, watching classmates cycle below. Another time, a whale drifted across the sky’s edge. I saw a house filled entirely with drawers, and from each one, birds burst forth in flight. Once, I dreamt I was wearing a VR headset, and there, in that simulated world, I met a friend who had long passed away. It felt eerily real, like I had stepped into a parallel universe. I painted all of these dreams, using the language of illustration to give them form.

AZ: Many media outlets have described your style as “Chinese structure with European Flair”. Do you resonate with that characterization?

SJ:I actually quite like it. After all, I grew up in China, steeped in traditional education, and later spent many years living abroad. Even when I try to paint in a more “Western” way, something innate always finds its way back into the work, something I didn’t place there consciously, but that surfaces on its own.

In fact, the older I get, the more I find myself drawn to the quiet beauty of Chinese culture. Take Peking Opera, for instance. When I was younger, it felt outdated, too slow, too stylized, something I couldn’t quite access. But it wasn’t that the opera was hard to understand; it was that I hadn’t yet reached the moment where I could truly listen. With time, you begin to realize that certain forms of beauty don’t demand to be understood immediately. They wait for you. If you allow yourself to slow down, to give a traditional painting or a melodic phrase the time it needs, something unfolds. And when it does, it’s unforgettable.

AZ: In your creative work, is there a sense of an “original home” you continue to return to? After living abroad for so many years, does that feeling of not fully belonging anywhere find its way into your art?

SJ: Yes, absolutely. Not long ago, I took part in an illustration competition themed around “Home”. For my submission, I drew what home tastes like: scenes of wrapping dumplings, skewers of lamb sizzling over coals, the aroma of Chinese toon scrambled with eggs. Friends gathered around a table, familiar laughter in the air. And landscapes from my hometown, quiet and enduring.To me, home is made of taste and scent, memory and warmth—all tightly woven together.

I once heard someone say, “Your stomach is your GPS—it will always locate home for you.” Later, I read a scientific explanation: the reason we long for the flavours of home is because our gut microbiome was first formed there. In other words, when you miss home, it’s not just nostalgia, it’s your body calling back to where it began. (laughs) I find that idea both amusing and strangely convincing.

That feeling of not fully belonging—it stays with me, too. When I return to China, I feel joy: friends, food, the ease of familiarity. But staying too long, and I start to sense that I don’t entirely belong there anymore. The same goes for the UK—it’s familiar, but never fully mine either. That tension—between places, between identities—naturally seeps into my work.

For instance, I once created a series about smoke, deliberately using traditional Chinese materials. It was my way of responding to questions of cultural identity. Later, I painted a group of animals dressed in Chinese traditional clothing—playful, but pointed. In those works, I was trying to explore belonging, displacement, and hybridity.

They are Chinese, yes—but they are also me, as I am now.

AZ: As both a mother and an artist, do you feel tension between these two roles?

SJ: I used to, very much so. When my children were little, my creative time was constantly being chopped into pieces.. I could only begin drawing after they fell asleep, usually around half past seven in the evening. Those “stolen time” were brief, but somehow it felt sacred.

Now that they’re in secondary school, the quiet hours of the day have been returned to me. I can finally breathe a little more easily, work with more intention. But to say it’s all perfectly balanced? That would be a stretch. I often joke that I’m a full-time mum, part-time artist. And when you look through art history, you’ll find that women who’ve managed to be both mothers and practicing artists are painfully few. That’s no coincidence—it’s the weight of reality.

Still, I believe women are built strong. God made man first and woman came after. The second attempt is always better than the first. (laughs)

AZ: If you could compare your life right now to a painting, what would it look like?

SJ: I’d say it’s a realistic painting, done in calm tones. My children are growing up. They don’t need my constant attention anymore, and that gives me space, finally, to do something for myself. It feels like the storm has just passed. There’s still a trace of it lingering in the air, but the sky has cleared. And here I am, rolling up my sleeves and ready to begin again.

My Dream (2021) by Shoran Jiang

AZ: 你平時的創作狀態是怎樣的?畫畫對你來說意味著什麼?

SJ: 畫畫對我來說算是一種治癒。有時心情煩躁,我會想畫一些「不走腦子」的東西,比如速寫或者隨手的小畫。以前孩子還小的時候,我常常帶著小本子出門邊走邊畫。家裡現在堆著很多這樣的本子,但它們都有一個共同點——沒有一本是完整用完的,就像橡皮擦,好像也從來沒有哪塊能被完全用完。不過真正做創作的時候,還是得進入「工作模式」。像我現在在準備上海的展覽,還差幾張作品,就得列清單、一個個完成。雖然很理性,但畫完後會特別開心,有成就感。

我也嘗試過一些系列創作,比如《夢境》系列。我畫過自己騎著龍飛在大學校園的上空,看著同學們騎車;夢見過鯨魚從天邊游過;還夢見過一間滿是抽屜的屋子,抽屜里飛出小鳥……甚至有一次,我夢見自己戴著VR眼鏡,看見一位已經去世的朋友,當時真的覺得好像進入了另一個平行空間。這些夢我都畫了下來,用的是插畫的風格。

AZ: 很多媒體評價你的作品風格是「漢骨歐風」。你自己喜歡這個說法嗎?

SJ: 我挺喜歡的。畢竟我從小在中國長大,受過傳統的教育,後來又長期在海外生活。就算我想把畫畫得「更西方」,骨子裡那些東西還是會跑出來。反而是年紀越大,我越覺得中國的東西特別美。就像京劇,年輕的時候會覺得有點「老氣」,聽不進去。其實不是京劇不好聽,而是你還沒到能聽懂它的年紀。等到願意靜下心來,給一幅傳統畫或一段唱腔更多時間,你就會發現它的美。

AZ: 在你的創作里,有沒有一個始終回望的「原鄉」?在異國生活多年,那種「不完全屬於」的狀態,會不會也進入到你的作品里?

SJ: 有的。我前陣子參加了一個插畫比賽,主題就是 「Home(家)」,我畫的其實就是「家的味道」。畫里有包餃子的場景、羊肉串、香椿炒蛋,還有和朋友們聚會的畫面,以及家鄉的風景。對我來說,home 就是這些和味覺、氣味緊緊綁在一起的記憶。

我之前聽過這樣一個描述,說「胃就是 GPS,它會把你定位到家鄉」。後來我又看到科學家的解釋,說人之所以會懷念家鄉的味道,是因為腸道菌群就是在那裡養成的。換句話說,當你想家的時候,其實是身體里的菌群在呼喚那個地方(笑)。

我也會有「不完全屬於哪一邊」的感覺。回國的時候很開心,能見朋友、吃熟悉的食物;可要真讓我長久待在那裡,又覺得不是完全屬於我的地方。在英國也是一樣。這種身份上的掙扎,其實也會自然進入到我的創作里。比如我曾經畫過一個《煙》的系列,特意選擇了中國的材料去完成,本身就是對文化身份的一種回應;後來我又畫過一些穿著中國傳統服飾的動物,把這種歸屬與認同更直接地呈現出來。對我來說,這些作品既是中國的,也是當下的我。

AZ: 那作為媽媽和藝術家,你會覺得這兩個身份之間有衝突嗎?

SJ: 以前確實會。孩子小的時候,我的創作時間被切得七零八落,只能等他們晚上七點半睡下,才開始動筆。那種「偷來的時光」雖然短暫,卻格外珍貴。現在他們上了中學,白天安靜的時光重新「歸還」給我,我能更從容一些。但要說完全平衡,其實很難。我常開玩笑說自己是「full-time mum, part-time artist(全職媽媽,兼職藝術家)」。縱觀藝術史,能夠同時兼顧母職和創作的女藝術家寥寥無幾,這並非偶然,而是現實的重量。但我也相信女性更強大——上帝先造男人,再造女人,第二次實驗當然會比第一次更成功。(笑)

AZ: 如果把你現在此刻的人生階段比喻成一幅畫,你覺得會是什麼樣的?

SJ: 我會說是一幅寫實的畫,色調平靜。孩子們漸漸長大,不再需要我時時操心,我也能騰出手來為自己做點什麼。就像暴風雨剛剛過去,空氣里還殘留著余韻,但天空已經放晴。我正想擼起袖子,再大干一場。

Smoke (2018) by Shoran Jiang

This conversation draws to a close with her reflection on that imagined painting. I was especially moved by the image Jiang Xiaoran described: a sea after the storm, so calm it can reflect your own shadow, quiet, steady, and already gestating the beginning of a new journey.

There is a sense of groundedness in that vision, a quiet power slowly gathering beneath the surface. As she says, painting has never been merely about technique—it is a way of thinking, of expressing, of being. Through this interview, we’ve caught a glimpse of her multifaceted life, as an artist, a mother, an educator. And perhaps, we’ve also come to understand another layer of meaning behind This Is Art: Art isn’t confined to books or classrooms. It lives in the everyday, in the smallest moments, the briefest glances, the softest laughter. It reminds us to look, to feel, to notice. And to discover, again and again, that this, too, is art—art that belongs to everyone.

這次訪談,便在她對那幅畫的暢想中告一段落。 我很喜歡姜嘯然構思的意象:像風暴後的海面,平靜得足以照見自己的影子,又在安穩之中孕育著下一段旅程的開端。那種感覺很踏實,也在悄悄積蓄著新的能量。如她所說,畫畫從來不只是技法,而是一種思考與表達的方式。 透過這場對談,我們看見了她作為藝術家、教育者與母親的多重身份,也看見了《這才是藝術》的另一層意義——它不僅屬於書頁與課堂,而是流淌在日常的細微之處,提醒我們去觀照、去體會,去在日常的一瞥一笑里發現,這才是屬於每個人的藝術。

Text by 撰文 x Dr. Hening Zhang 張鶴寧

Edited by 編輯 x Michelle Yu 余小悦