Wayne McGregor:Infinite Bodies is a landmark exhibition by internationally acclaimed choreographer Wayne McGregor, presented at Somerset House as a highlight of the institution’s 25th anniversary programme. Conceived not as a retrospective but as a forward-looking inquiry, the exhibition positions choreography as a method for thinking through the body in an era shaped by algorithms, artificial intelligence, and immersive technologies.

We are delighted to speak with Dr Cliff Lauson, co-curator of Infinite Bodies, about his collaboration with Wayne McGregor and the curatorial challenge of “choreographing” the gallery space.

《韋恩·麥克格雷戈: 無限之軀》(Wayne McGregor: Infinite Bodies)是英國編舞家Wayne McGregor於 Somerset House 呈現的重要展覽,亦是該機構 25 週年的重點項目。展覽以舞蹈為核心方法,結合人工智慧、動態捕捉、沉浸式影像、聲場與機械裝置,探索在科技深度介入的時代,身體如何被延展、轉譯與重新定義。

我們很高興與《無限之軀》(Infinite Bodies)的聯合策展人 Cliff Lauson 博士進行了對談,探討他與韋恩·麥克格雷戈(Wayne McGregor)的合作,以及如何將編舞轉譯為展覽空間語言的策展挑戰。

AZ: Wayne’s work is so rooted in the body and in process. As a curator, how did you begin translating something so temporal and kinetic into a spatial, visual exhibition?

CL: You’re right. Wayne’s practice is very much about the body, kinetics and choreography, and a lot of what he does happens on stage. From the beginning, we wanted to make an exhibition that focuses on the work off the stage, or alongside it. For Wayne, choreography is a term and a concept that extends beyond performance. It’s really about the intentionality of movement.

The practice of studying movement, and of arranging people or objects in space, whether on stage or elsewhere, becomes formalised as dance. But there are many broader ways of thinking about choreography. In an exhibition context, there’s an interesting reversal: it’s the public, the visitors, who are moving through the space, encountering one thing after another.

As a curator, almost like a director or choreographer, what you can do is to shape that experience. You can change how people move through the space and how they experience it. Ultimately, the aim of the exhibition is to look at the body, movement and technology, and to encourage people to become more aware of their own physical presence, to think with their bodies, and to reflect on their own bodily or physical intelligence.

AZ: Whenever work moves from one context to another, something shifts. In your opinion, what is lost when dance leaves the stage and enters the gallery, and what new possibilities open up because of that move?

CL: It definitely changes. On stage, especially in a traditional theatre with an auditorium, everything is very tightly controlled. The stage is in front, the audience sits over there, and what happens on and around the stage is carefully choreographed. A performance on a Thursday night will be almost the same as the one on a Sunday afternoon, or even if the show tours to San Francisco, it will feel very similar.

In an exhibition, it’s different. You set up a series of works in space, but the variable element is the audience, how they move through the space and engage with what is there. Some people might spend a long time in one area, while others move quickly through different zones. People bring different attention and interest to different aspects of the work.

When putting the show together, we had to think: if someone spends about an hour with the exhibition, what kind of experiences do we want them to have? How can we reveal different aspects of the work in ways that vary from person to person? It’s about creating a space where each visitor can have their own layered and unique encounter with the work.

AZ: You spent time at Industrial Light & Magic, working closely with advanced technologies. How did that experience shape the way you think about bringing VFX, motion capture, immersive media and AI into a curatorial context?

CL: It was a really nice coming together of old collaborators in a way. Wayne had previously worked with Industrial Light & Magic on ABBA Voyage, which is a huge project with its own purpose-built auditorium, it’s a permanent installation in a way. They’d always wanted to work together again after that, even though it was quite a few years ago, so it felt meaningful that this exhibition created the opportunity for that collaboration to resume.

I myself spent a short period on secondment at ILM many years ago. It wasn’t long, but it was incredibly formative. It really opened my eyes to how filmmaking works at that scale, the visual effects pipeline, and the kinds of creative possibilities that come with cutting-edge technology. As a curator, I’m very familiar with what artists are usually able to access and present within galleries or exhibition contexts. That’s quite different from the world of commercial, Hollywood-style filmmaking.

So when we started thinking about new commissions for the exhibition, working with ILM expanded what felt possible. They were incredibly generous in supporting the project, particularly through motion capture and visual effects, which allowed us to create a kind of digital, virtual performance that could be presented at life scale within the galleries. That shift bringing those technologies into an exhibition context, was both technically exciting and conceptually important for the show.

AZ: Looking across Wayne’s thirty-year practice, how did you decide what to show, what to leave out, and what needed to be rethought specifically for the gallery?

CL: That’s a good question. Like any project with a partly retrospective dimension, it began with a long period of research. The exhibition took around two years to develop, and at the start that meant looking across the full scope of Wayne’s practice, understanding everything he has made over the past thirty years. A lot of that material is well documented in his studio archive, but there are also projects that are much less formally recorded, which Wayne had to talk us through from memory. So there was quite a lot of filtering.

From early on, we were clear that this wasn’t going to be an exhibition about the stage. It wasn’t about costumes, set design, or playbills. Instead, we were much more interested in Wayne’s more experimental work, particularly the collaborations, and the ways he has tested ideas across different disciplines. From there, we began identifying works that represented key collaborative moments, and slowly started to connect them through shared themes around the body, movement, and technology.

Wayne has been working with technology for as long as he’s been making work arguably since he was a child, even if that began more as play. It’s always run alongside his choreographic practice rather than sitting apart from it. So the exhibition naturally became about collaboration: about different ways of thinking through the body and movement, and about working with other kinds of expertise.

Once we had a sense of the key works, the realities of the gallery space came into play. You’re always working within a fixed architecture, so certain pieces begin to anchor themselves in particular rooms. Some works had to be adapted, or newly made, in order to sit coherently within that spatial framework. There’s quite a natural process to that. And then, once the main structure of the exhibition is in place, you usually find a few opportunities to fill gaps, to refine the rhythm of the show and bring everything into balance.

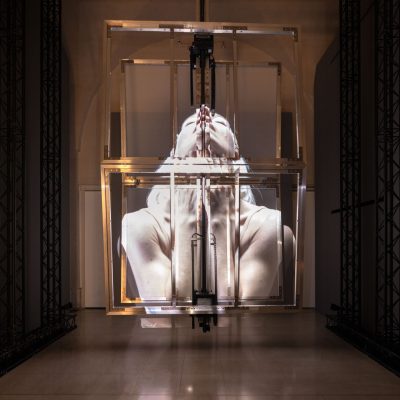

Model with Future Self (2012) Random International + Wayne McGregor + Max Richter. Part of Wayne McGregor Infinite Bodies exhibition at Somerset House. Photo Andrea Rosetti

AZ: When viewers experience both human performers and machine-driven movement in the same space, what kind of perceptual or emotional dialogue did you aim to create?

CL: I think one of the central themes of the exhibition is really about how we relate to technology. With robotics in particular, a machine can initially feel a little colder, simply because it’s mechanical, it’s not an android.

But we always come back to the ideas behind the projects. Take No One Is an Island, for example. At its core, it’s about motion, and about how we, as human beings, recognise movement through sight. The robot becomes a way of making that process visible. When you see it moving, especially in relation to the dancers, the question shifts to: how do you relate to this machine?

Wayne often talks about this in terms of kinesthetic empathy. “Kinesthetic” in the sense of movement and physical presence, but also how you feel in response to what you’re seeing. And that idea doesn’t just apply to robots; it extends to digital work as well, to digital avatars.

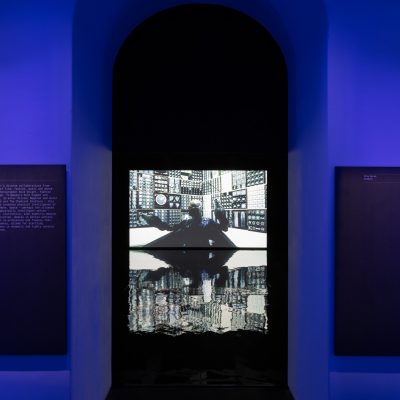

Model with A Body for AI (2025) Wayne McGregor + Ben Cullen Williams. Part of Wayne McGregor Infinite Bodies exhibition at Somerset House. Photo:David Parry PA Media Assignments

AZ: No One Is an Island was actually my favourite part of the exhibition. Watching the dancers move with the machine was really powerful. It was inspiring to read the exhibition text about how we don’t just recognise human forms and cues, but can also feel an instinctive empathy towards machines. From your perspective, what does it take, creatively and technically, to choreograph and curate that kind of human–machine relationship? The machine didn’t feel cold at all, but almost harmonious, like it was moving naturally with the dancers. Was that sense of harmony something you were aiming for, or were you hoping to provoke a different response?

CL: I mean, that’s certainly one way of reading it, and I think it’s important to say we wouldn’t want to prescribe how people relate to the machines. The question we’re really putting out there is: what kind of kinesthetic relationship do you have with the machine?

What’s interesting to me is the way you describe that in terms of temperature, that it feels warmer, that it doesn’t feel cold. Someone else might describe it differently: they might say the machine seems to have a personality, or they might reach for another metaphor altogether. And all of those responses are valid.

From an exhibition-making point of view, what we tried to do was create spaces where you could really focus on that relationship. That’s why each installation sits on its own, in a single room. You’re given the time and the space to look, to think about what’s happening, and to feel it before moving on to another work that’s asking a different question.

And then, of course, it shifts again if you’ve seen the work performed live. When the dancers and the machine are moving together in that context, they’re telling a different story altogether. That becomes another layer of the experience, sitting alongside what you encounter in the gallery.

Model with AISOMA (2025) Wayne McGregor + Google Arts & Culture Lab. Part of Wayne McGregor Infinite Bodies exhibition at Somerset House. Photo: David Parry PA Media Assignments

AZ: The Living Archive and AISOMA turn choreographic memory into something generative. How do you think about that shift, from archive, to dataset, to the creation of new movement?

CL: I think one of the key things with the Living Archive and AISOMA is really about how the data is used. We can digitise all sorts of things in the world and store them as files, but what’s quite unique about Wayne is that his entire library of movement has been digitised and structured as a database. That’s an enormous amount of work, and a huge amount of expertise behind it. We’re talking about over 600,000 movement phrases. So the real question becomes: what do you actually do with all of that?

What’s distinctive about Wayne’s practice is that this data isn’t just archived and left alone. He actively uses it in the studio when he’s composing and developing new work with dancers. In the gallery is something he’ll also use in rehearsals, as a way to disrupt habits, shift things slightly, or spark new ideas. It’s not about dancers copying what the computer generates. It’s more like a kind of movement-based mood board, something to bounce ideas off.

For the exhibition, the challenge was how to open that process up to the public for the first time. The project with Google has been running since 2019, but for this show it’s been updated and re-presented so visitors can physically engage with it. You can offer a gesture or a movement, and AISOMA responds. It’s playful, it’s intuitive, and it gives you a real sense of what’s possible, while still reflecting something that’s very much part of Wayne’s ongoing studio practice

AZ: A Body for AI raises questions about what a body might be beyond biology. How does this work push the exhibition’s wider exploration of embodiment in the age of machine learning?

CL: I suppose what A Body for AI brings together is this very particular combination of a large robotic sculpture, sound, and video. It approaches questions around the machine and the body in a more poetic way, through imagery alongside filmed footage, rather than trying to make a direct political statement. It’s about how these elements sit together and resonate with one another.

What’s quite unusual about the work is that it’s based on an earlier piece, A Body for Harnasie (2024), where the same robotic sculpture was suspended above a full orchestra performing live. That kind of setup is incredibly rare: you have this monumental machine, live music, projection, dancers, and movement all operating together. It’s a convergence of different art forms that you don’t often see, especially with something as physically imposing as a giant robot positioned over an orchestra, and that tension between scale, sound, and embodiment carries through into the exhibition version of the work.

AZ: With a work that’s so technologically and mechanically present, how did you make sure the technology didn’t overpower the emotional or conceptual experience for the viewer?

CL: It’s something we were always very conscious of, but in many ways that balance comes directly from Wayne and his practice. He’s deeply interested in technology, but not just because something is new or shiny. It’s always about what that technology can do, what it might unlock, or how it allows us to ask a question differently, or even to ask a completely new question altogether.

Because technology is constantly changing, the questions around it are constantly shifting too. And when you put all of that together, what it really comes back to is this ongoing reflection on what it means to be human. In that sense, the work becomes slightly self-reflexive.

AZ: Accessibility plays an important role in the public programme. How did you approach this, and what alternative ways of sensing or embodying the exhibition did you hope to open up for neurodivergent or visually impaired audiences?

CL: Good question. With all our exhibitions, we try to think about accessibility in a number of different ways. One thing we do regularly is to run relaxed sessions, which have become a popular way for people to engage with exhibitions on their own terms.

With this show in particular, our public programme producer organised several different types of events. We hosted a BSL-led event, and we also ran movement workshops specifically for neurodivergent participants. One of those workshops took its lead from work that Studio Wayne McGregor has been developing in this area for some time.

So there’s a strong continuity there, Wayne and the studio have long been engaged with questions of access and alternative modes of embodiment, and the public programme allowed us to extend that thinking into the exhibition space.

AZ: Finally, after bringing Infinite Bodies together, what new questions about bodies, cognition, or technology are you still carrying with you?

CL: Many of those questions became much clearer through the development of On the Other Earth. Because that work, in particular, feels like the latest stage in Wayne’s ongoing exploration of dance and technology. It’s a fully immersive, 3D, performance-based piece, and it brings together many of the ideas that surface throughout the exhibition, but in a much more all-encompassing way.

What it really starts to probe is how we experience things in virtual space, or perhaps more accurately in space. There’s a blurring of boundaries there, which is something that began with virtual reality and augmented reality, and then developed further through different forms of mixed reality. This work sits somewhere in that territory, a kind of augmented mixed reality. You can see through the glasses, so you’re still aware of the physical environment, but at the same time there’s so much happening around you.

When I experienced it, it genuinely felt futuristic, almost like being on a holodeck in Star Trek, where an entire environment is generated around you. That’s very different from traditional VR, where you’re wearing a heavy headset and looking at screens in front of your eyes. And the window is the goggles. With On the Other Earth, it felt much more like the dancers were actually in the room, at life scale, with a stronger sense of physical presence. So I think some of the most pressing questions that stay with me are about that the further intersection of virtual and mixed realities.

Through Wayne McGregor:Infinite Bodies, the exhibition moves beyond extending dance into the gallery and instead becomes an active experimental system—one in which bodies, technologies, and modes of perception continually test, negotiate, and reconfigure one another.

As Dr. Cliff Lauson suggests, this is not an exhibition about technology as spectacle, but about how we come to understand ourselves through our encounters with algorithms, machines, and virtual spaces. As choreography migrates from stage to exhibition, from body to dataset, from memory to generation, Wayne McGregor:Infinite Bodies offers no definitive conclusions. What it leaves us with is an open, ongoing question: in an ever-expanding technological environment, how might the body continue to think, to sense, and to become?

AZ: Wayne 的創作深深扎根於身體與過程之中。作為策展人,你是如何開始把這種時間性、動態性的創作轉譯成一個空間化、視覺化的展覽?

CL: 是的,Wayne 的創作實踐確實深深根植於身體、動能和編舞之中,而他大量的作品也發生在舞台上。從一開始,我們就希望策劃一個展覽,把焦點放在舞台之外,或與舞台並行的創作實踐。對 Wayne 而言,「編舞」並不僅僅是一種表演形式,而是一個延伸至舞台之外的概念,它關乎的是動作的意圖性。

對動作的研究,以及在空間中安排人或物,無論是在舞台上,或是在其他場域,最終會被形式化為舞蹈。但事實上,編舞也可以被放在更廣義的框架中來思考。在展覽的語境裡,出現了一種有趣的角色反轉:移動的不再只是表演者,而是觀眾本身,他們在空間中穿行,依序遇見不同的作品。

作為策展人,某種程度上就像導演或編舞者一樣,你有機會塑造這樣的經驗,調整人們在空間中的移動方式,以及他們感知空間的方式。歸根究底,這次展覽的核心目的便是透過身體、動作與科技的交織,邀請觀眾對自身的身體存在產生更強烈的意識,學習用身體去思考,並反思自身的身體性或物理智能。

AZ: 當作品從一種情境轉移到另一種情境時,總會產生變化。當舞蹈離開舞台、進入美術館空間時,你覺得失去了什麼?而同時,又因為這樣的轉移開啟了哪些新的可能?

CL: 確實差別很大。在舞台上,尤其是那種傳統、有觀眾席的劇院空間裡,一切其實都被控制得非常精準。舞台在前面,觀眾坐在那裡,舞台上以及舞台周圍發生的事情,幾乎都是被仔細編排好的。所以一場星期四晚上的演出跟星期天下午的那一場,基本上不會有太大差別;就算作品巡演到洛杉磯,整體感受也會非常接近。

但在展覽裡,情況就完全不一樣了。你是在空間中放置一系列作品,可是真正充滿變數的其實是觀眾本身:他們怎麼移動、怎麼停留、怎麼和作品互動。有些人可能會在某一個區域待很久,有些人則快速穿梭在不同空間之間。每個人帶進來的注意力、好奇心,甚至情緒狀態,也都不一樣。

所以在策劃這個展覽的時候,我們一直在想:如果一個觀眾大概花一個小時看完整個展覽,我們希望他們經歷的是什麼?我們要怎麼安排,才能讓作品的不同維度以各種不同的方式被打開、被感知?最後,其實就是在嘗試創造一個空間,讓每一位觀眾都能以自己的節奏,形成一段層次豐富、而且獨一無二的觀看經驗。

AZ: 你曾在工業光魔(Industrial Light & Magic)工作,並與先進科技密切合作。這段經驗如何影響你將視覺特效、動作捕捉、沉浸式媒體與 AI 納入策展脈絡的思考方式?

CL: 對我來說,這個項目其實是一個很美好的「重逢」。因為 Wayne 之前就曾和 ILM 合作過《ABBA Voyage》,那是一個非常龐大的作品, 有自己的劇院空間,是一個永久性的裝置。那是一個非常重要的合作。從那之後,其實雙方一直都很希望能再次一起工作,只是已經過了很多 年。

所以這次展覽能成為他們再度合作的契機,我覺得非常棒。而我自己也曾在很多年前短暫地以借調的形式在 ILM 工作過一段時間,雖然時間不 ⻑,但對我來說影響非常深。那段經驗真的打開了我的眼界,讓我更理解電影製作是如何運作的、視覺特效的製作流程,以及在最前沿的技術 條件下,創作可以走到多遠。

作為策展人,我其實非常清楚,大多數藝術家在美術館或展覽空間中,能夠使用和呈現的技術資源是有限的。但當你進入的是一個像好萊塢商 業電影製作那樣的系統時,那完全是另一個層級的思考方式。

在為這次展覽構思新的委託作品時,ILM 給了我們非常大的支持,無論是動作捕捉,還是所有隨之而來的視覺特效製作。他們幫助我們創造出 一種數位、虛擬的表演形式,並且在展覽空間中以接近真人尺度的方式呈現出來。這對整個策展構想來說,是非常關鍵的一步。

AZ: 回顧 Wayne 三十年的創作實踐,你是如何決定哪些作品要呈現、哪些要捨去,又有哪些是必須為美術館空間重新思考的?

CL: 這是一個很好的問題。我想任何帶有一點回顧性質的項目其實都會經歷類似的過程。這個展覽前後大概籌備了兩年,一開始真的就是從非常廣泛的研究開始,把他整個創作脈絡攤開來看,試著弄清楚他做過的一切。其中有很多內容都保存在他自己的工作室檔案裡,但也有不少作品其實紀錄得沒那麼完整,那些就需要他靠記憶親自跟我們說明。

所以第一步其實就是不斷地篩選。很明確的一點是,這個展覽並不是要談舞台本身,也不是做一個關於服裝、舞台設計或節目單的展覽。我們更關心的是他如何以一種比較激進的方式和不同的合作者一起實驗。

接著我們就開始思考:哪些作品最能代表關鍵性的合作關係?然後再把它們放進「身體、動作與科技」這幾個主軸之下來理解。Wayne 幾乎從很小的時候就一直在接觸科技,也許一開始只是玩,但它確實一直都在他的生活裡,並且長期與他的舞蹈和編舞實踐並行發展。

所以這個展覽其實更多關於「合作」,關於如何跨領域、與不同專業背景的人一起思考身體與動作。接下來,我們就把認為最關鍵的作品集合起來。不過現實層面上,你永遠是在一個有限的空間裡工作,所以必須開始思考哪些作品放在哪裡。有些作品需要調整,甚至重新製作,才能適應展覽空間,讓整體成立。這其實是一個很自然發生的過程。等到核心內容大致確定之後,最後就會出現一些可以填補空間的機會,讓整艘「船」能夠完整、平衡地航行。

AZ: 當觀眾在同一個空間中同時面對真人表演者與由機器驅動的運動時,你希望他們之間產生怎樣的感知或情感對話?

CL: 這之間確實存在某種關係。我想這場展覽其中一個核心主題,就是我們如何與科技建立關係。以機器人為例,機械往往給人一種比較冷的感覺,因為它是機械性的,它不是仿真人(android)。

但我認為我們總是會回到作品背後的概念本身。以《No One Is an Island》為例,這件作品其實是在探討「運動」,以及我們人類如何透過視覺來辨識運動。機器人在這裡某種程度上成為一種輔助,幫助我們理解這個過程。在舞蹈與動作的呈現中,作品向觀眾提出一個問題:你如何與這個機器建立關係?

Wayne 常用的一個詞是「動覺共感(kinaesthetic empathy)」,指的是動作與身體的存在感,而「共感」則是你在觀看時所產生的情感回應。這其實也是一個可以延伸到數位作品的問題,例如數位化身(digital avatar)。

AZ:《No One Is an Island》是我在整個展覽裡最有感觸的一件作品。看到舞者和機械一起移動、一起「跳舞」的時候,我會感覺那個機械並不是冰冷的,反而有一種很自然的和諧感。我記得展覽文字裡提到,我們不只是如何辨識人類的動作與身體線索,也會對機械產生一種本能的共感。從你的角度來看,在創作和技術上,要怎麼編舞、又怎麼策展,才能讓這樣的人機關係成立?你們是刻意想讓觀眾感受到這種人與機械之間的和諧嗎?還是其實更希望引發觀眾去思考、甚至產生不同的情緒反應?

CL: 那當然只是一種解讀方式,我覺得很重要的一點是,我們並不想規定觀眾應該如何去感受這些機器。我們真正想提出的問題是:你和這個機器之間,會建立什麼樣的動覺關係呢?

我覺得有趣的是,你用「溫度」來形容這個感受,它感覺比較溫暖,不覺得冰冷。而其他觀者可能會有不同的描述:有人覺得這個機器似乎有自己的個性,也有人可能會用完全不同的隱喻。這些都是合理的感受。

從展覽策展的角度,我們嘗試做的是創造一些空間,讓觀眾可以專注於這種關係。這就是為什麼每一個裝置都有自己的獨立空間,一個房間放一件作品。你有時間,也有空間去看、去思考發生了什麼、去感受它,然後再移動到下一件提出不同問題的作品。

當然,如果你看過作品的現場表演,這個感受又會再次改變。當舞者和機器一起移動時,它們講述的是完全不同的故事。這就成為了另一層經驗,和你在展覽空間裡所遇到的感受並行存在。

AZ: 《The Living Archive》和 AISOMA 將編舞記憶轉化為一種可生成的系統。你如何看待這種從「檔案」到「數據集」,再到「新動作生成」的轉變?

CL: 我認為《The Living Archive》和AISOMA的關鍵點在於如何使用這些資料。我們可以把世界上各種東西數位化、存成檔案,但 Wayne 的特別之處在於,他整個動作資料庫都被數位化,並整理成一個完整的資料庫。這是一個巨大的工作,也需要相當高的專業能力。光是動作片段就超過六十萬條。所以真正的問題是:這麼大量的資料,到底該怎麼用呢?

Wayne 的做法很特別,他不只是把資料存起來,放著不動。他在工作室裡創作新作品時會積極使用這些資料,和舞者一起構思、發展新作品。你在展覽中看到的其實也是他在排練時會用的方式,用來打破慣性、稍微改變一些東西,或者激發新的靈感。這並不是讓舞者去模仿電腦生成的動作,而更像是一種以動作為基礎的「靈感板」,用來互相激發想法。

對於這次展覽來說,挑戰就在於如何把這個創作過程首次開放給公眾。其實這個與 Google 的合作計畫從 2019 年就開始了,但為了這次展覽,它被更新並重新呈現,讓觀眾可以親身互動。你可以做一個手勢或動作,AISOMA 會回應你。這個過程很有趣,也很直覺,能讓人真實感受到可能性,同時也反映了這其實就是 Wayne 日常工作室實踐的一部分。

AZ:《A Body for AI》提出了關於非生物性身體的思考。這件作品如何推進展覽對於機器學習時代「具身性」(embodiment)的更廣泛探討?

CL: 我想這件作品結合了大型機械雕塑、聲音和影像。它更偏向詩意地呈現機器、身體,以及景觀影像與拍攝影像的融合。整體感覺更像是一種和諧共鳴,而非對這些議題做出強烈的政治宣示。

這件作品的特別之處在於,它源自一件名為《A Body for Harnasie (2024)》的作品,當時同樣的機械雕塑懸掛在一整個現場樂團上方演奏。這種安排非常罕見:巨大機器、現場音樂、投影、舞者與動作同時運作。不同藝術形式在這裡交融,而像這樣一個龐大機器懸置在樂團之上的張力,從規模、聲音到身體化表現,都延續到展覽版本之中。

AZ: 面對一件如此科技感與機械感十足的作品,你如何確保技術不會壓過觀眾的情感或概念體驗?

CL: 這點我們一直都放在心上。但從某種角度來說,這也源自於 Wayne 本人及他的創作實踐。他對科技非常感興趣,但我會說,不只是因為某件事物新穎或閃亮,而是因為他想提出問題——例如,這項技術有什麼潛力去解鎖新的可能性?或者讓我們以不同的方式提出問題,甚至提出全新的問題?科技一直在變,所以圍繞它的問題也在不斷變化。把這一切綜合起來,其實核心還是對『何謂人類』的持續反思。在這個意義上,作品本身帶有一種自我反思的特質。

AZ: 無障礙性在公共項目中扮演重要角色。你們是如何著手處理這一點的?你希望為神經多樣性或視覺障礙的觀眾開啟哪些替代的感知或體驗方式?

CL: 很好的問題。我們在策劃每個展覽時,都會嘗試從不同角度去思考可及性。我們經常會舉辦放鬆場次(relaxed sessions),這種形式讓觀眾可以以自己的節奏、自己的方式來參與展覽,也變得越來越受歡迎。

針對這次展覽,我們的公共項目製作人策劃了幾種不同類型的活動。我們有英國手語(BSL)導覽活動,也為神經多樣性參與者設計了動作工作坊。其中一個工作坊就是借鑒了 Wayne McGregor 工作室長期在這方面的研究和實踐。所以其實有很強的延續性,Wayne 和工作室一直關注可及性和替代性的身體表現方式,而這次公眾項目也讓我們可以把這些思考延伸到展覽空間裡。

AZ: 在完成《Infinite Bodies》之後,關於身體、認知或科技,你還有哪些新的問題仍帶在心中?

CL: 我覺得很多關於身體、感知和科技的問題都在《On the Other Earth》中被聚焦出來了。這件作品特別明顯地呈現了 Wayne 持續探索舞蹈與科技的最新階段。它是一個完全沉浸式的 3D 表演作品,把展覽中許多出現的理念整合起來,但更全面、更包羅萬象。它開始真正探討的是,我們如何在虛擬空間中,或者更準確地說,在空間裡體驗事物。這裡有一種邊界模糊的感覺,這種概念最早是從虛擬實境和擴增實境開始的,然後再透過各種混合實境形式進一步發展。《On the Other Earth》就處在這個範疇中,一種擴增混合實境。你透過眼鏡仍然能看到實體環境,但同時周圍又有很多事情在發生。當我親身體驗時,真的有種未來感,幾乎像《星際迷航》裡的全息艙(holodeck),整個環境在你周圍生成。這跟傳統 VR 很不一樣,傳統 VR 要戴上厚重的頭戴裝置,眼前只有螢幕,而那個「窗戶」就是眼鏡本身。而在《On the Other Earth》中,感覺所有舞者真的在房間裡,以真人大小呈現,帶來更強烈的存在感。所以,對我來說,最值得思考的問題之一,就是虛擬與混合實境進一步交叉的可能性。

Model with Audience (2008) Random International. Part of Wayne McGregor Infinite Bodies exhibition at Somerset House.Photo: Andrea Rossetti

Company Wayne McGregor (Kevin Beyer) with Future Self (2012) Random International + Wayne McGregor + Max Richter. Part of Wayne McGregor Infinite Bodies exhibition at Somerset House. Photo by Ravi Deepres

透過《韋恩麥格:無限之軀》,展覽不再只是舞蹈的延伸場域,而成為一個持續運作的實驗系統。在其中,身體、科技與感知不斷彼此試探、協商與重組。正如 Dr Cliff Lauson 所揭示的,這並非關於技術本身的展示,而是關於我們如何在與算法、機械與虛擬空間的交會中,重新理解自身的存在方式。當編舞從舞台進入展覽,從身體進入資料庫,從記憶轉化為生成,展覽所開啟的並不是答案,而是一個仍在展開中的提問:在一個被不斷擴張的技術環境中,身體將如何繼續思考、感知與成為自己?

Interview and Text by 採訪及撰文 x Rinka Fan

Edited by 編輯 x Michelle Yu