Alice Neel: Hot off the Griddle

Barbican Centre

16 February – 21 May 2023

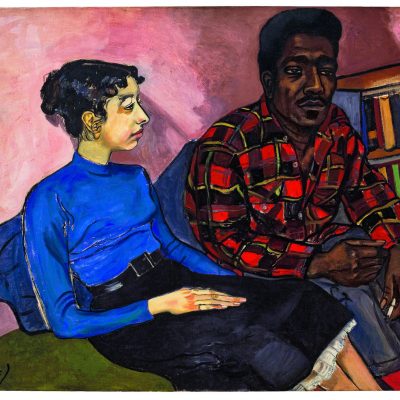

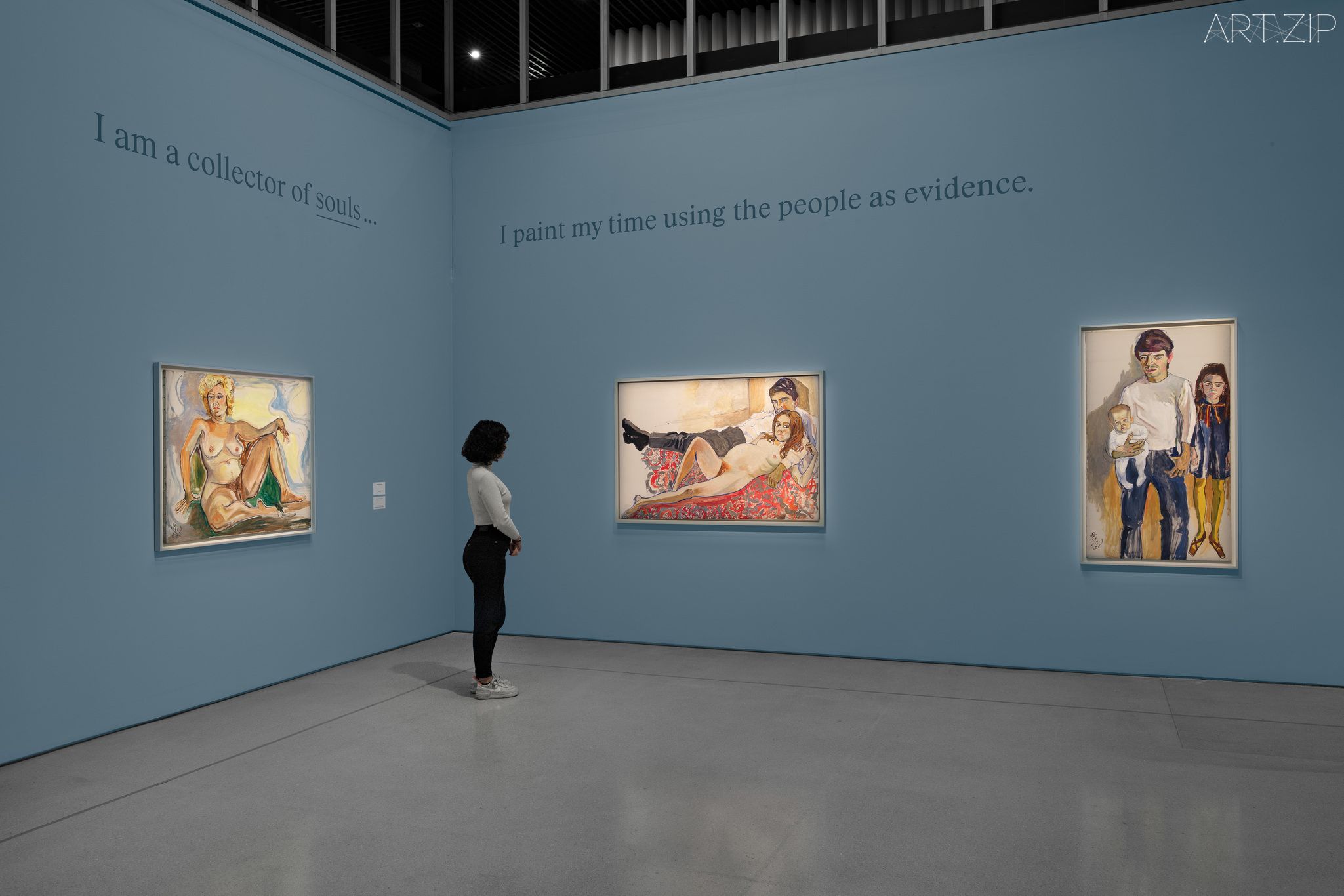

The Barbican Centre is presenting the largest UK exhibition to date of the work of Alice Neel. Neel was one of the most creative and radical American artists of the 20th century, known as the “court painter of the underground.” Her paintings celebrated individuals who were often marginalised in society, including labour leaders, pregnant women, Black and Puerto Rican children, Greenwich Village eccentrics, civil rights activists, and queer performers. Neel referred to herself as “a collector of souls,” and her paintings radiate with her sense of the humanity and dignity of each subject.

‘Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle’ showcases works spanning Neel’s 60-year career, drawn from international public and private collections. The exhibition features Neel’s vibrant portraits, shown alongside archival material from the time, including photography, letters, and film. Despite painting figuratively during a time when it was deeply unfashionable to do so, Neel persisted with her distinctive, expressionistic style. ‘A radical, creative artist undervalued for much of her six-decade career, Neel dedicated her life to producing vital, revealing portraits of New York’s bohemian scene’, said Will Gompertz, Barbican Artistic Director.

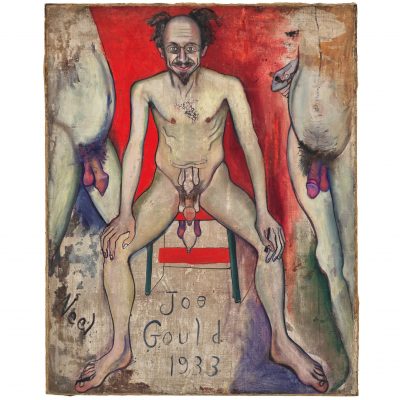

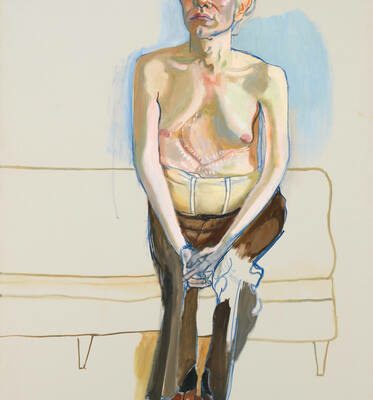

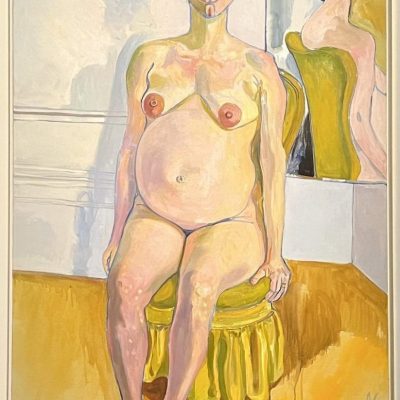

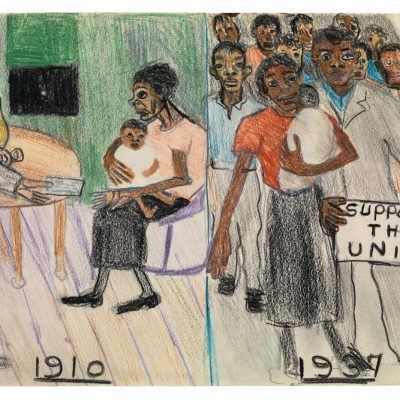

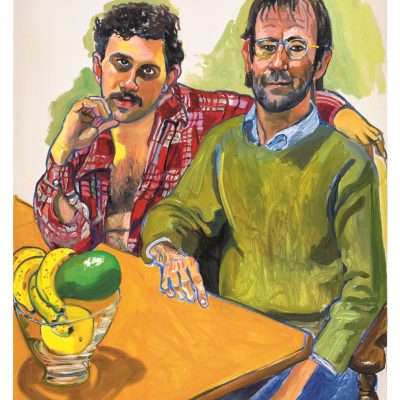

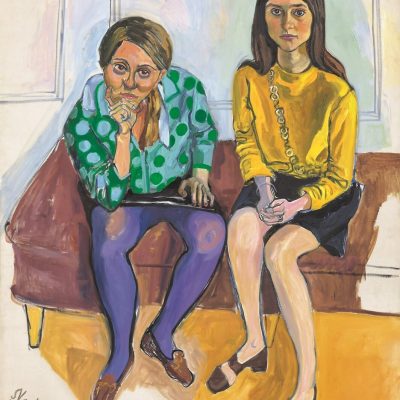

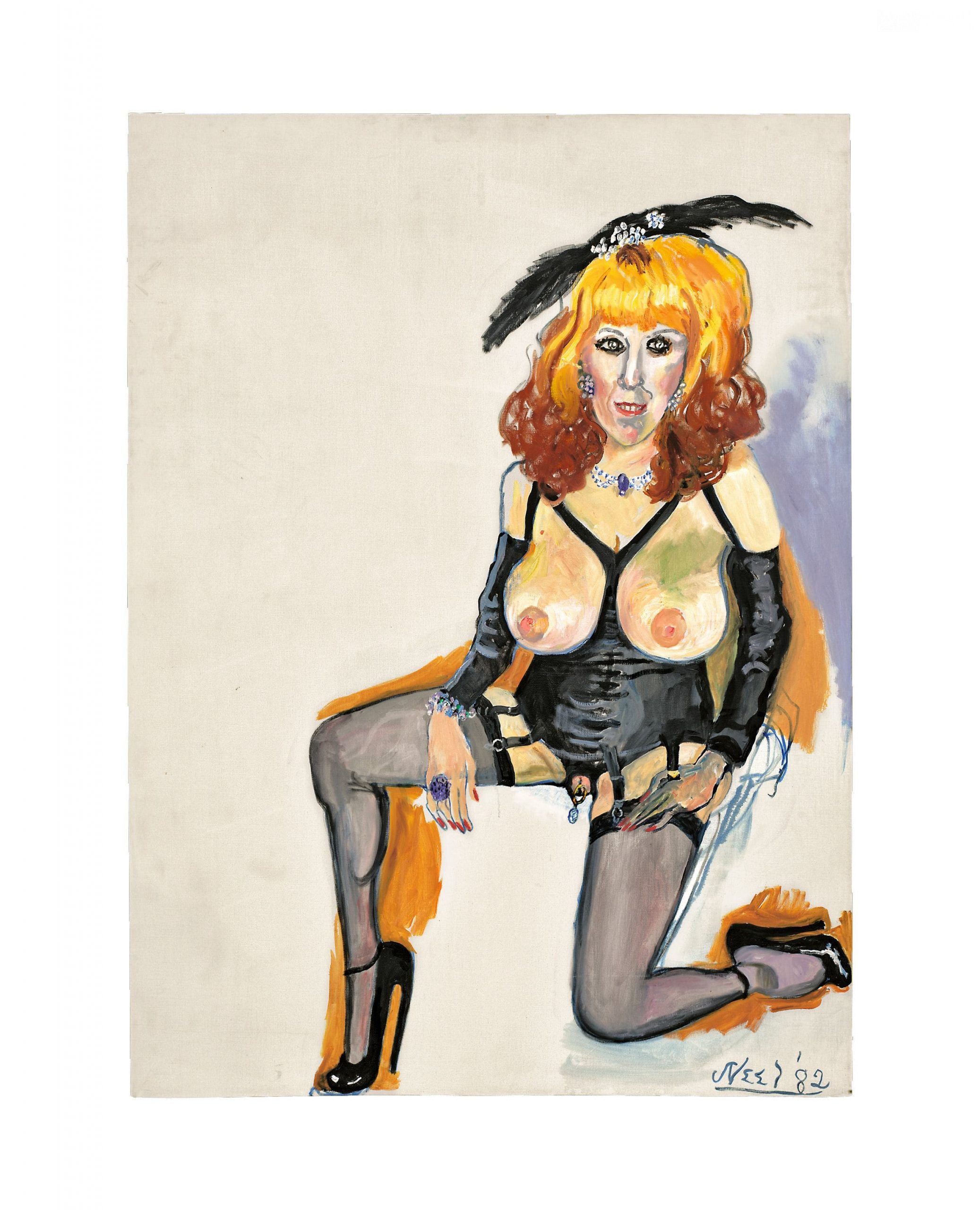

The exhibition sets Neel’s work amid her shifting cultural context, from her formative year in Havana in 1925 with her husband, the Cuban artist Carlos Enríquez, to Spanish Harlem, where she made her home for much of the 1940s and 50s. The exhibition also includes Neel’s later portrait paintings from the 1960s and 1970s, when she made some of her most celebrated work. Highlights include ‘The Spanish Family’ (1943), ‘Support the Union’ (1937), a portrait of Andy Warhol (1970), ‘Self-Portrait’ (1980) Neel’s nude self-portrait, which she painted when she was 80 years old; and a portrait of performance artist and sex activist ‘Annie Sprinkle’ (1982).

Alice Neel. Annie Sprinkle, 1982 © The Estate of Alice Neel . Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel

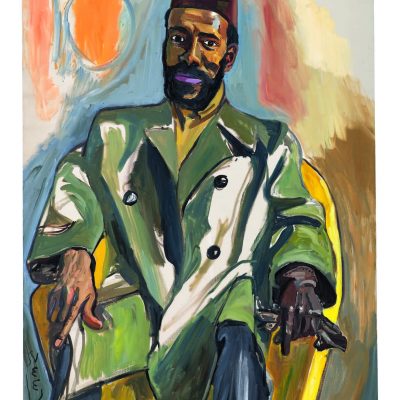

Neel’s works are remarkable for their depth of empathy, as she set out to reveal the inequalities and pressures experienced by the people she painted. Her eclectic line-up of portraits from this era includes many figures whom she admired for their political commitments, from the Marxist filmmaker Sam Brody to the communist intellectual Harold Cruse. As a member of the US Communist Party, her radical portraits caught the attention of the FBI, and in recent years, the politics of her work has given her cult status among a younger generation of artists.

“Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle” is an exciting opportunity for visitors to experience the extraordinary power of Neel’s work and her understanding of the politics of seeing and what it means to feel seen. This exhibition provides an excellent opportunity to explore the creations of a pioneering artist who was ahead of her time and whose legacy continues to inspire and captivate audiences today.

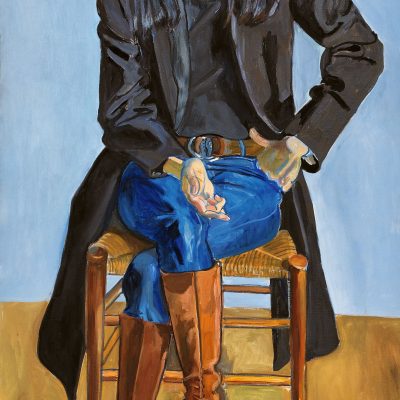

Alice Neel Hot Off The Griddle, Installation view, Barbican Art Gallery, 16 February – 21 May 2023 (c) Eva Herzog

Interview with Annabel Bai Jackson——All Walks of Life by Alice Neel

Alice Neel’s portrait paintings demonstrate her unique authenticity and social concern. Her emphasis on the physical features and language of the portraits, as well as her in-depth, inside-out depiction of nudity, all reflect her distinctive painting style. We are lucky to interview the assistant curator of this exhibition, Annabel Bai Jackson. Her insights have given us a deeper understanding of Alice Neel’s creative philosophy.

AZ: Alice Neel once mentioned that she found it hard to have her own self-portrait, and she prefers to paint herself naked. What is the reason behind this? What kind of image do you think she would like to present herself in the painting? Or, what do you see in her self-portrait?

AJ: It’s interesting to read what Neel says on the affective dimension of portrait painting, which she sometimes describes as a kind of self-erasure. In a 1984 interview, she said, ‘In the process I become the person for a couple of hours, so when they leave and I’m finished, I feel disoriented. I have no self. I don’t belong anywhere … It’s terrible, this feeling, but it just comes because of this powerful identification I make with the person.’ It’s quite unsettling, that sense of total abandon and then having to return or withdraw to a deserted place. So I wonder if the struggle to complete Self-Portrait came in part from turning that process in on itself: there must have been some slippage in the dynamics of Neel’s ‘powerful identification’ when painting the self-portrait, creating the weird paradox of abandoning yourself to produce a work of yourself.

Alice Neel, Self-Portrait, 1980 © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel

AZ: The exhibition chronicles the evolution of Alice Neel’s paintings from her early years to her later works. The subjects, the colours she used, the background of the sitters, the brushstrokes, have changed. Do you have a personal favourite of these paintings? Or a particular period?

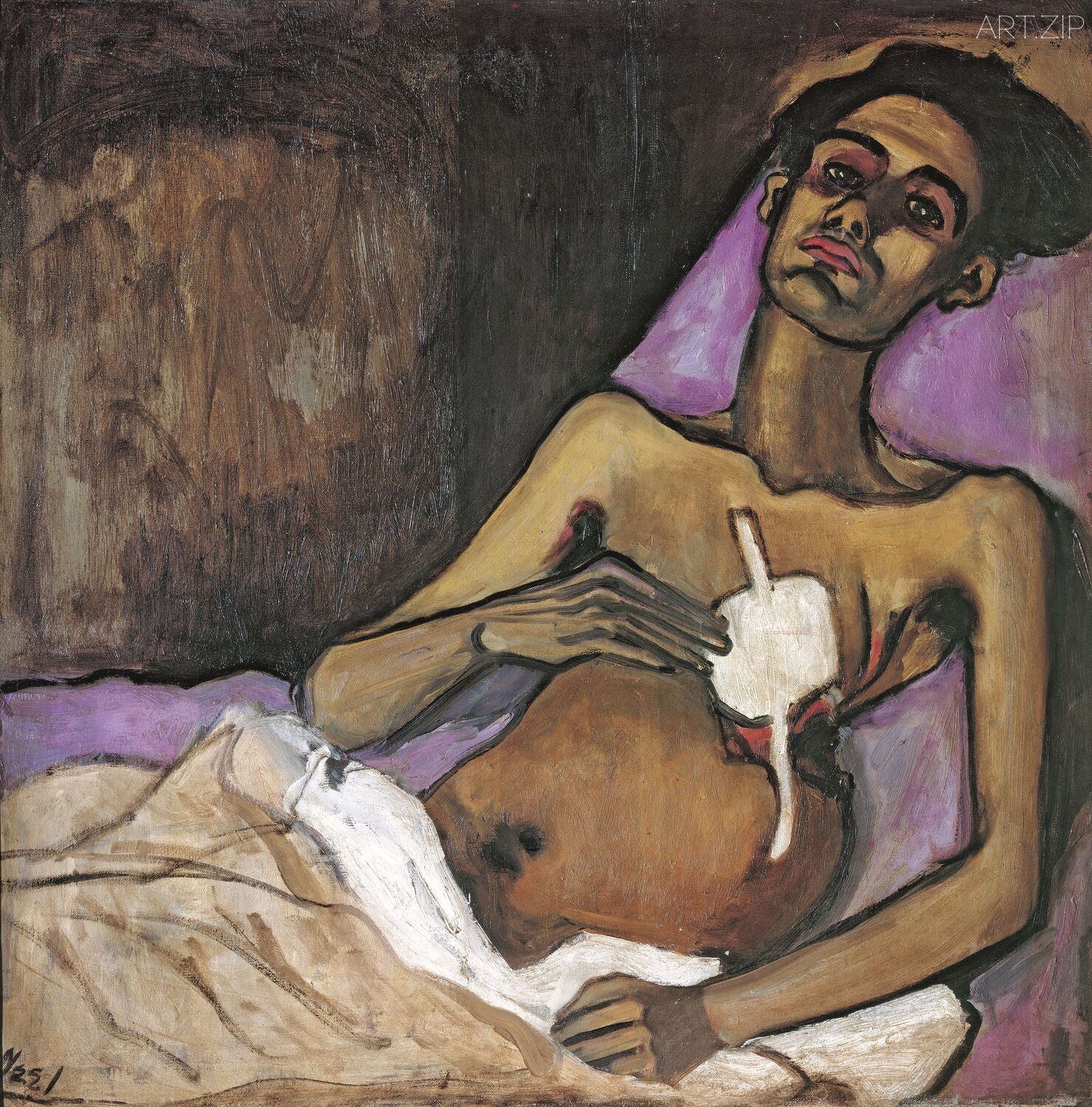

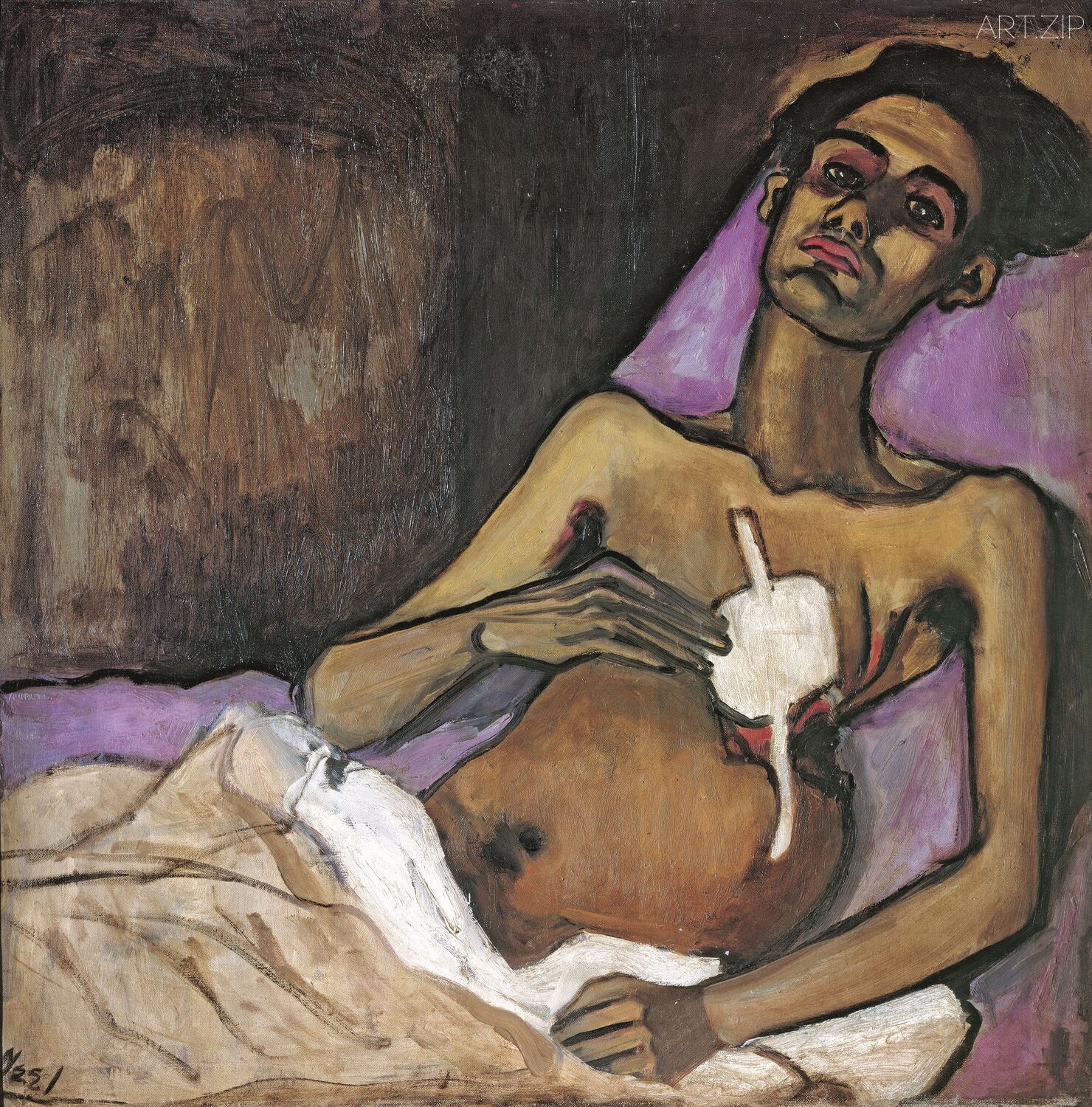

AJ: All the paintings are glorious, but I do have a few personal favourites! T.B. Harlem (1940) is a very moving portrait of a man called Carlos, who was undergoing treatment for Tuberculosis (TB) at the time. I imagine it’s no easy job to convey the brutality of this illness, and the way it weakens you physically, while also conveying a sense of such complex interiority – but that’s just what I think Neel achieves in this portrait. Elaine Scarry (who wrote one of my favourite texts, The Body in Pain [1985]), talks about how ‘physical pain has no voice, but when it at last finds a voice, it begins to tell a story’; I often think of that process of voice being negated and then found when looking at Carlos’ expression, at once resigned and dignified. A point we also make in the exhibition guide is the significance of Neel calling the painting T.B. Harlem instead of e.g. Carlos – a decision that highlights TB as a social phenomenon, rather than just an individual one. Illness, while in some ways so individualising, is also not apolitical, and can’t easily be divorced from the social context it appears in.

Alice Neel. T.B. Harlem, 1940 © The Estate of Alice Neel . C ourtesy The Estate of Alice Neel

AZ: How did the sitters in Alice Neel’s paintings change from her early works to her later works?

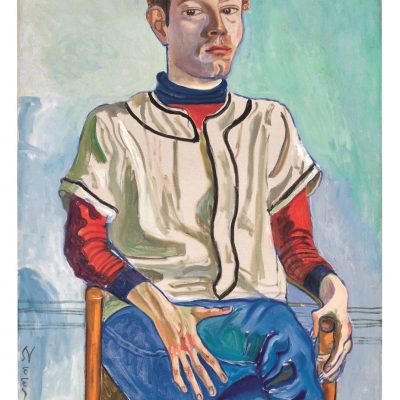

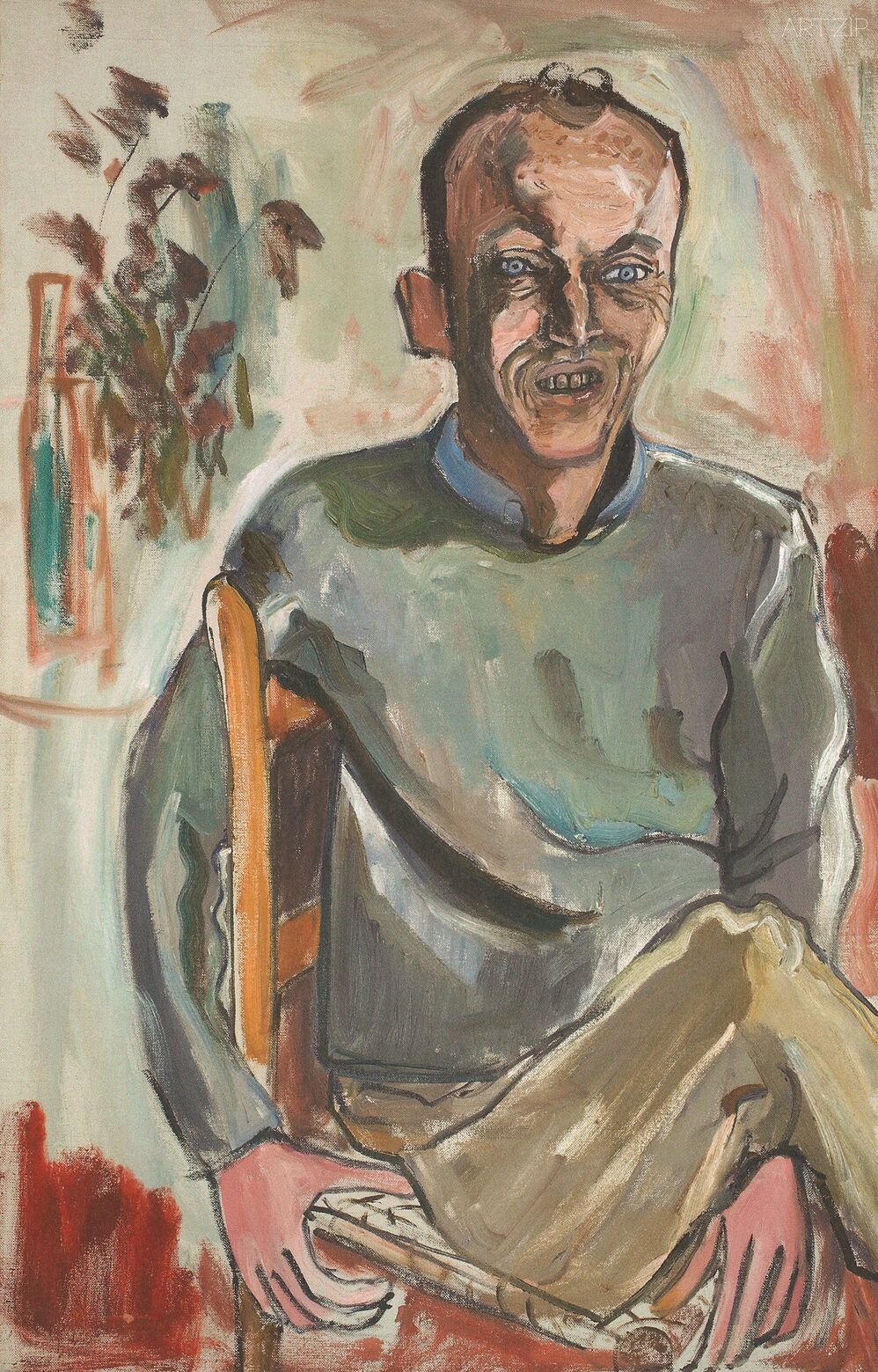

AJ: There were a couple of factors that shaped who sat for Neel. A lot of it was obviously geography – as Neel painted almost entirely from life, whichever neighbourhood she was living in influenced her choice of sitter – but it also came down to the shifting socio-political and cultural context of America (or at least New York). So in the works from the 1930s, we see a mix of bohemians, unions, and strike action; in the mid-century works, we have a lot of Communist Party USA members and intellectuals; and in the later works, we begin to see radical activists and feminists, and artists from the Factory scene. Neel liked to say, ‘I am the century’, and in a way, her choice of sitter reflected that sense of being coeval with the rea. Shifts in confidence also determined who peopled Neel’s canvas. In the show, we mark the painting of Frank O’Hara (1960) as a kind of watershed moment: he was the first ‘big name’ in the New York art world who she found the courage to approach, and from then on we have people like Andy Warhol, Gerard Malanga, and Linda Nochlin. But even when she was painting illustrious cultural figures, she never forgot those she was most consistently devoted to capturing in her work, i.e. those who were marginalised in some way by mainstream culture. Making portraits of them – a genre historically limited to the white and wealthy – was a way of dignifying them when the rest of society had failed to do so.

Alice Neel Frank O’Hara, 1960 © The Estate of Alice Neel . C ourtesy The Estate of Alice Neel.

AZ: Female artists encountered many obstacles in the past. How were the states of most of them? Were they more dedicated for art’s sake in art practice or did they strive for recognition and success as male artists of the same period?

AJ: Neel wanted recognition, and I admire the fact that she didn’t shy away from that. In an interview towards the end of her life, she said, ‘nothing could be more important than that one’s work be shown,’ and joked that she would write a book called ‘Life Begins at 70’ – acknowledging the rush of success she had in her later years, especially after her first major show in 1974 at the Whitney. But she never compromised on her vision to get there: she was painting right through the heyday of abstract expressionism, but persisted with her figurative work and always stuck to her fascination with people. I think it’s also worth noting that ‘recognition’ and ‘success’ don’t take place in a vacuum; there are always forms of advocacy at play. A group of radical feminists took against the omission of Neel in the broader cultural canon and actually petitioned the Whitney to give her a solo show – one of the sitters whose portrait we have in the exhibition, Irene Peslikis of Marxist Girl, was involved in that. So as much as Neel’s first major ‘success’ came was a wonderful recognition of her talent, it was also partially a product of that redressal.

Alice Neel Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis), 1972 © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel.

AZ: The depiction of naked subjects in art has undergone significant changes over time. As a viewer, particularly for conservative audiences, what are some ways to interpret and appreciate these types of paintings and their boldness and explicitness?

AJ: I think it’s important to remember that within the realm of Neel’s ‘naked subjects’, there’s a lot of variation. For instance, Joe Gould (1933), who’s endowed with three layers of genitalia, has a degree of whimsy or irony that’s absent from the tension found in Margaret Evans Pregnant (1978) and its depiction of the late stages of pregnancy – or the striking vulnerability of Andy Warhol (1970) bearing his surgical wounds. So I think as a viewer, it’s helpful to take each one on its own terms, and to recognise the different registers that emerge from the category of ‘Neel’s naked portraits’. We’ve organised the exhibition chronologically, so we don’t have a bay dedicated to this genre of painting in particular: instead, these works (hopefully) interact with the others on display through style, expression, mood, posture, etc. And viewers can feel rest assured that the ‘boldness’ or ‘explicitness’ is never one-dimensional or gratuitous.

愛麗絲·尼爾: 新鮮出爐

巴比肯藝術中心

2023年2月16日至5月21日

巴比肯藝術中心舉辦了迄今為止英國規模最大的愛麗絲·尼爾 (Alice Neel) 作品展《愛麗絲·尼爾: 新鮮出爐(Alice Neel: Hot off the Griddle)》。尼爾是 20 世紀美國最具創造力和最激進的藝術家之一,被稱為“地下宮廷畫家”。她的畫作歌頌了經常被社會邊緣化的人,包括勞工領袖、孕婦、黑人和波多黎各兒童、格林威治村的怪人、民權社運人士和酷兒表演者。尼爾稱自己為”靈魂的收藏家”,她的畫作充滿了對每個主題人物的人性和尊嚴的感知。

《愛麗絲·尼爾: 新鮮出爐》展示了尼爾 60 年職業生涯中的作品,這些作品來自國際公共收藏及私人收藏。展覽以尼爾充滿活力的肖像作品為特色,並與當時的社會檔案材料一起展示,包括攝影、信件和電影。儘管那是在一個非常不流行具象繪畫的時代,但尼爾仍然堅持她獨特的表現主義風格。巴比肯藝術總監威爾·岡波茲(Will Gompertz)表示:“作為一名激進、富有創造力的藝術家,在她六十年職業生涯的大部分時間裡,她的價值都被低估了,尼爾畢生致力於為紐約的波西米亞場景創作了重要的、具有啟發性的肖像畫。”

此次展覽將尼爾的作品置於她當時不斷變化的文化背景中,從1925年她與丈夫、古巴藝術家卡洛斯·恩里克斯 (Carlos Enríquez) 在哈瓦那成長的那一年,到她在1940年代和50年代的大部分時間里安家的西班牙哈萊姆區。展覽還包括了尼爾在1960年代和70年代後期的肖像畫,當時她創作了一些最著名的作品,亮點包括《西班牙家庭》(1943 )、《支持聯盟》(1937 )、《安迪·沃霍爾(Andy Warhol)》(1970),尼爾80歲時畫的裸體自畫像——《自畫像》(1980), 以及表演藝術家和性學社運人士《安妮·斯娉科爾(Annie Sprinkle)》(1982)的肖像。

尼爾的作品以其深刻的同理心而著稱,她試圖揭示她筆下的人們所經歷的不平等和壓力。她不拘一格地捕捉了這個時代的社會群像,包括許多她因其政治承諾而欽佩的人物,從馬克思主義電影製作人薩姆·布羅迪(Sam Brody)到共產主義知識分子哈羅德·克魯斯(Harold Cruse)。作為美國共產黨的一員,她激進的肖像畫引起了聯邦調查局的注意,而近年來,她作品的政治屬性使她在年輕一代藝術家中享有崇高地位。

《愛麗絲·尼爾:新鮮出爐》為觀者提供了一個激動人心的機會,讓他們體驗尼爾作品的非凡力量,以及尼爾對看見和被看見意味著什麼的政治意義。此次展覽探索了這位領先於時代的先驅藝術家的作品,尼爾的遺產將繼續激勵和吸引著當今的觀眾。

專訪策展人安娜貝爾·杰克遜(Annabel Bai Jackson)——愛麗絲·尼爾的社會眾生相

愛麗絲·尼爾的肖像繪畫顯示出其獨特的真實性與社會關懷。她對肖像的身體特徵和語言的重視,以及對裸體深入、從內而外的描繪,都體現出了她別具一格的繪畫風格。我們有幸採訪了這次展覽的助理策展人安娜貝爾·杰克遜(Annabel Bai Jackson),她的見解讓我們對愛麗絲·尼爾的創作理念有了更深入的理解。

AZ:尼爾曾經提到,她發現創作自己的自畫像很困難,如果畫的話更偏向畫自己的裸體畫像。這背後的原因是什麼呢?你認為她想通過畫作展現出自己什麼樣的形象?又或者說,你在她的自畫像中看到了什麼?

AJ:解讀尼爾談到肖像畫的情感維度是很有趣的,她有時將其描述為某種自我消解。在1984年的一次採訪中,她說:“在這個創作自畫像的過程中,我成為了那個‘人’,幾個小時後作品完成了,這個‘人’離開了,我感到很迷茫。我彷彿沒有了自我,我不屬於任何地方……這種感覺很不好受,但這種感覺只隨著我對這個‘人’的強烈認同而出現。” 那種完全放棄然後又要返回或撤退到一個荒蕪之地的感覺會令人不安。所以我也好奇,努力完成自畫像的這種掙扎是否也反映到創作過程中:在畫自畫像時,尼爾的“強烈認同感”一定會有一些微妙的變化,而這就會創造出一個奇怪的悖論,那就是放棄自我而去創作一個關於自己的作品。

Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, 2023 ©Eva Herzog

AZ:這次展覽記錄了尼爾從早期到後期作品的演變歷程。她畫的主題、使用的顏色、模特的背景描繪、運用的筆觸都變化不少。你有沒有個人特別鍾愛的作品?又或者特別喜歡的一個時期的作品?

AJ:我認為所有的畫都很美,但確實有幾幅是我個人特別喜歡的!《T.B. Harlem》(1940)是一幅非常動人的肖像畫,描繪了一個名叫卡洛斯(Carlos)的男人,他當時正在接受肺結核的治療。我想,要表達這種疾病的殘酷性和它在身體上的虛弱感,同時又要表達出如此複雜的內心世界,這絕非易事。但我認為尼爾在這幅肖像畫中就做到了這一點。埃萊恩·斯卡里(Elaine Scarry)她寫過一篇我最喜歡的文章,《受苦之軀(The Body in Pain)》(1985),文章裡提到“身體的痛苦是無聲的,但當它最終找到聲音要表達時,它便開始講述一個故事”;我常常在看卡洛斯的表情時,想到這個被否定然後又被找到聲音的過程,他既看似已經認命,又充滿尊嚴。我們在展覽指南中也提到,尼爾將這幅畫命名為《T.B. Harlem》而不是例如《卡洛斯(Carlos)》,這個決定突出了肺結核作為一種社會現象,而不僅僅是個人的現象。疾病,雖然在某些方面是極其個體化的,但也不是非政治的,它不能輕易地與其出現的社會環境脫離開來。

Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, 2023 ©Eva Herzog

AZ:尼爾早期到後期肖像畫裡的模特有怎樣的變化?

AJ:決定尼爾肖像畫模特有幾個因素。其中一個很明顯的因素是地理位置,因為她幾乎完全是描繪現實的作品,因此她所生活的社區影響了她選擇模特的決定。但這也歸結於美國(或至少是紐約)社會政治和文化背景的變化。所以在1930年代的作品中,我們看到了波西米亞人、工會和罷工運動的描繪;在20世紀中葉的作品中,我們看到了許多美國共產黨成員和知識分子;而在後期的作品中,我們開始看到激進的社運人士和女權主義者,以及工廠場景中的藝術家。

尼爾喜歡說,“我就是這個世紀”,在某種程度上,她選擇的模特反映了這種與現實同步的感覺。她自信的轉變也決定了誰出現在她的畫布上。在展覽中,我們將《弗蘭克·奧哈拉(Frank O’Hara, 1960)》的肖像標記為一個分水嶺時刻:他是尼爾敢接觸的第一位紐約藝術界名人,從那時起,我們便開始看到了更多名人畫像,如安迪·沃霍爾(Andy Warhol)、傑拉德·馬蘭加(Gerard Malanga)和琳達·諾克林(Linda Nochlin)等。但即使在畫文化名人時,她也從未忘記那些她一直努力用繪畫捕捉的人群,即那些在某種程度上被主流文化邊緣化的人。我們都知道,歷史上通常是為白人和富人繪製肖像,但尼爾則選擇為被邊緣化的人士繪製肖像。即使社會忽視他們,但尼爾通過繪畫的方式賦予了這些被邊緣化人士該有的尊嚴。

AZ:女性藝術家在過去遇到了許多阻礙。當時她們的狀況如何?她們在藝術實踐中是更為藝術本身奉獻,還是像同期的男性藝術家一樣,努力尋求認可和成功?

AJ:尼爾想要得到認可,我很佩服她沒有回避這一點。在她晚年的一次採訪中,她說,“沒有什麼比展示自己的作品更重要”,並開玩笑說她會寫一本名為《生活從70歲開始(Life Begins at 70)》的書,她承認在晚年獲得巨大的成功,特別是在1974年在惠特尼美術館的首次大型個展之後。但她從來沒有為了達到這個目標而妥協:她在抽象表現主義的全盛時期一直堅持創作具象作品,並始終對人們充滿好奇。我認為值得注意的是,“認可”和“成功”並不是憑空出現的;總是有各種各樣的倡導運動在起作用。一群激進的女權主義者對尼爾在文化界被忽視感到不滿,向惠特尼美術館請願,要求為她舉辦個展。展覽中有一幅作品畫的是馬克思主義女孩伊雷娜·佩斯利基斯(Irene Peslikis),她就參與了這次請願運動。所以,尼爾的第一次重大的“成功”不僅是對她才華的極大認可,從某種程度上來說,也可以說是那個時代“糾錯”的產物。

AZ:藝術中裸體主題的描繪隨時間的推移發生了顯著的變化。作為觀眾,特別是對於保守的觀眾來說,有哪些方式可以幫助解讀和欣賞這類型的畫作以及它們這種“大膽”和“赤裸”?

AJ:我認為重要的是要記住,尼爾的“裸體主題”有很多變化。例如,《喬·古爾德(Joe Gould,1933)》擁有三層生殖器,這具有一定的詼諧或諷刺意味,而在《瑪格麗特·埃文斯懷孕晚期(Margaret Evans Pregnant,1978)》描繪中顯示的是緊張感,而《安迪·沃霍爾(1970年)》肖像畫裡顯示的則是手術傷口的脆弱感。因此作為觀者,我認為每張畫都有自己想要傳遞的信息,我們要認識到尼爾的裸體肖像畫中各不相同的表達。這次我們按時間順序來策劃展覽,而沒有專門為裸體肖像作品設立一個主題展區;相反地,我們希望這些裸體作品能通過風格、表達、情緒、姿態等與其他展品產生對話或互動。觀眾可以放心,這種“大膽”或“裸露”的內容絕不是單一表述或無緣無故、毫無意義的。

Edited by 编辑 x Victoria Huang 黄婧

Interviewed by 採訪 x Michelle Yu 余小悅

Translated by 翻譯 x Rinka Fan, Michelle Yu 余小悅