A juxtaposition occurs by virtue of the turning of the opening page of the listed works of catalogue for the Oskar Reinhardt Collection at the Courtauld. As both collections were formed in a similar time frame, they find a seamless resonance across the spectrum of works exhibited. The first painting by Goya appears as a form of arrest of attention, as if it is staging the notion that the early Modern Period begins with a shock related to the figuring of genre. Both paintings might appear to serve as the staging of the surprise within their respective genres by passing over into something other through an act of exposure, as if each depiction is folded back upon itself. Both paintings might be viewed as a staging of recesses that hint at a darkening of mood. The three salmon steaks of Goya appear to have an eye like cavity, and this gives rise to a half-haunted feeling of that issue from the steaks. Partley this can be seen as if returning the gaze to rupture the spell of passivity that the nature of dead meat appears to invite. If this apprehension has any basis in perception, then it would indicate a still deeper shift into a sphere of abjection.

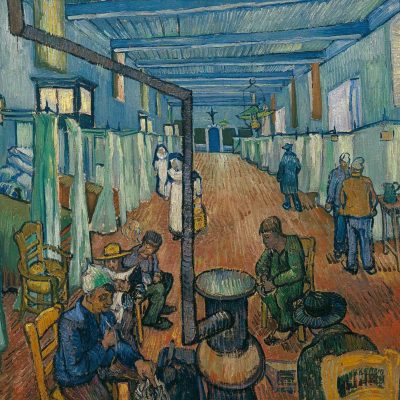

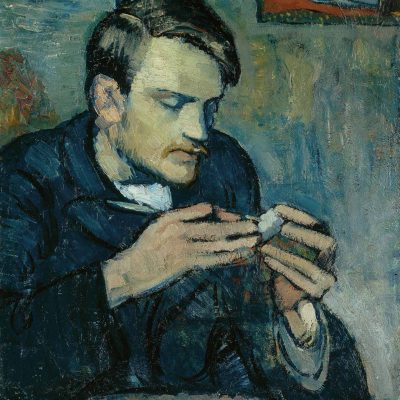

If the advent of Modernism is fully inaugurated with Impressionism, and with this, the revelation of light cast on everyday life, then these two paintings sit uncomfortably within such a schema. Another way of viewing this is perhaps see them as paintings of the darkening of Modernism as the implication of the unconscious starts to take hold. The painting of Theodore Gericault is part of a group of portraits that depict madness, delusion, or mania. The eyes are cast as looking away from daylight, back into the bottomless pit of the void or the endless night. It is a depiction of a raw like sensation of loneliness that is interminable in its hold of a subject who has become adrift from its centred hold over is being. This then is the polar night of extreme reification which terror has cast it eyes over. When Gericault painted the fragmentary limbs of the dead, not only to visually impart its witnessing, but had a desire to be saturated by the smell of death as part of painting it. Death or madness for him was the presentation of an extreme immersion of all the senses within the interiority of the sensation of loss.

Perhaps it is possible to see these two works as not an inaugural gesture of modernity that requires of us to expand our criteria of what lies within and beneath of it and thus this switching becomes part of the canon of modernity. Therefore, these works can be understood not only as acts depicting the forces of estrangement that will run through its course as its limit but as also establishing the sense of difference. In effect this indicates that modernity was not just an experience of continuity but also a parallel experience of discontinuity. Both these paintings then serve as an early warning system in which the lines that can register extreme limit within its aesthetic orbit. What these paintings manifest is a prelude to a state of rupture in the form of Goya’s ‘Black Paintings’ (1820-23) and the Gericault’s ‘The Raft of the Medusa’ (1818-19) that includes all the fragmentary studies undertaken for its eventual execution. Both instances confront both the limit of making manifest the despair of the relationship of ethics and politics, even if from entirely different frameworks and it is the nature of dealing with such a confrontation that is the mark of a deeper sense of a modernist impulse. This difference is that of the intensely private paintings of Goya and the public facing painting of Gericault but they both enact stages of a struggle in which figures emerge out of a black ground in both a literal and ontological sense. If early modernism was a pursuit of the struggle to liberate colour from mimesis, then these early episodes related to blackness and shadow serve to indicate another starting point for modernism, or the more complex idea, that modernism was not a singular manifestation but a movement of different currencies and encounters.

Francisco Goya, A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, 1820–1823

Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa, 1818–1819.

翻開庫爾托美術館奧斯卡·萊因哈特(Oskar Reinhardt)收藏的畫冊目錄,映入眼簾的是一種強烈的並置對比。由於這兩個收藏形成於相近時期,它們在作品的選擇與呈現方式上產生了某種共鳴。戈雅的第一幅畫作瞬間抓住觀者的目光,彷彿演示了一種觀念——即早期現代主義的開端,不是平緩的過渡,而是類型畫的震撼與顛覆。這兩幅畫都以某種「曝光」的方式突破了自身的類型界限,轉化為帶有異質性的存在。它們不再只是單純的靜物畫或肖像畫,而是超越了既定分類,彷彿每一筆描繪都在折疊回自身,讓畫面顯得既熟悉又陌生。它們像是「隱蔽角落」的視覺再現,暗示著氛圍的幽暗與不安。

戈雅畫中的三塊鮭魚排帶有「眼睛般的空洞」,散發出詭異的凝視感,彷彿某種幽靈般的存在從魚肉中滲出。這種效果不僅塑造了一種半超自然的氛圍,也像是在回應觀者的目光,打破死肉所帶來的沉寂與被動。如果這種直覺在感知層面上成立,那麼它標誌著一種更深層次的墜落——進入「廢棄狀態」(abjection)。如果說印象派的興起標誌著現代主義的正式開端——即光線對日常生活的揭示——那麼這兩幅畫在這一框架內顯得格格不入。另一種解讀方式則是,它們象徵著「現代主義的暗面」,無意識的力量開始滲透藝術創作。傑利柯的畫作屬於一幅描繪瘋狂、妄想與狂熱的人物肖像。畫中人物的目光游離,彷彿避開白晝,凝視無底深淵,或沉陷於無盡的黑夜。他的表情透出一種原始的孤獨——無休止的囚禁,將他與自身的核心剝離,彷彿靈魂已然漂離軀殼,遊蕩在一片虛無之中。這是一種極端物化的暗夜,恐懼在其中投下陰影。傑利柯筆下的死亡與瘋狂,不只是視覺上的再現,而是一種極端的感官沉浸。據說,他在畫支離破碎的屍肢時,並不滿足於單純「見證」死亡,而是刻意讓自己被死亡的氣息所包圍,甚至長時間接觸腐爛的屍體,以全方位體驗失落與毀滅的感知。

或許,這兩幅畫帶來的並不是現代性的開端,而是讓我們重新思考現代性的內涵——提醒我們深入表象之下,洞察那些潛伏的深層結構。它們的存在,讓現代性不再只是線性發展的敘事,而包含著異化與斷裂的經驗。換句話說,現代性並非單向度的連續進程,而是一場充滿對立、矛盾與間斷的歷程。

這兩幅畫也可視為一種「預警系統」,標示出藝術在美學範疇內所能觸及的極限。它們預示了隨後的劇烈斷裂——戈雅的 《黑色畫作》(1820-23)與傑利柯的 《梅杜薩之筏》(1818-19),後者更包含大量片段式習作,為最終作品鋪墊。無論是從倫理還是政治角度來看,這兩種表現形式都直面絕望,雖然出發點不同,卻都展開了一場關於人類極限的對峙。如何回應這種對峙,或許正是「現代主義衝動」的核心所在。戈雅的作品極度私密,而傑利柯則面向公眾,兩者的視角迥異,但都展現了一場掙扎——畫中的形象從黑暗背景中浮現,不僅是視覺上的顯現,更是一種存在論層面的顯影。

如果說早期現代主義是一場將色彩從自然模仿中解放的鬥爭,那麼這些圍繞黑暗與陰影的探索則提供了另一種可能的現代性起點。或者更複雜地說,現代性從來不是單一的現象,而是一場由多重力量交織、相互碰撞的運動。

Goya to Impressionism. Masterpieces from the Oskar Reinhart Collection

14 February – 26 May 2025

The Courtauld Gallery

Text by Jonathan Miles

Edited by Michelle Yu