———————————————————————————————————————

撰文:傑夫·戴爾

Written by: Geoff Dyer

翻譯:于暢

Translated by: Chang Yu

圖片提供:Geoff Dyer

Photography by/ image by courtesy of:Geoff Dyer

———————————————————————————————————————

INTRODUCTION

“It’s a small world” is an idiom that expresses ‘surprise’ that people or events in different places are connected.

常言道:“世界真小 (It’s a small world)!”,萬事萬物在不同的地方仍有冥冥中的聯繫總讓人驚嘆。

In his essay ‘Small World’ Geoff Dyer looks at the world through photographs and the paradoxical relationship at the heart of the tourist experience;

在《小世界》裡,傑夫·戴爾通過反思照片的意義與旅行者心中的矛盾關係來審視世界,

“sightseeing in particular and holidaying generally are often the opposite of fun – partly because of all the other tourists.”

“觀光也好——或就整個旅遊活動來說,有時候並非是一種享受——而是受罪——一定程度上是由於其他遊客的存在。”

This is a common experience that we share with one another, but what ‘sights’ are we seeing when we are sightseeing?

這是一個“與人分享”的普遍經驗,但是我們在“觀光”旅遊時“觀”的到底是何種“光”呢?

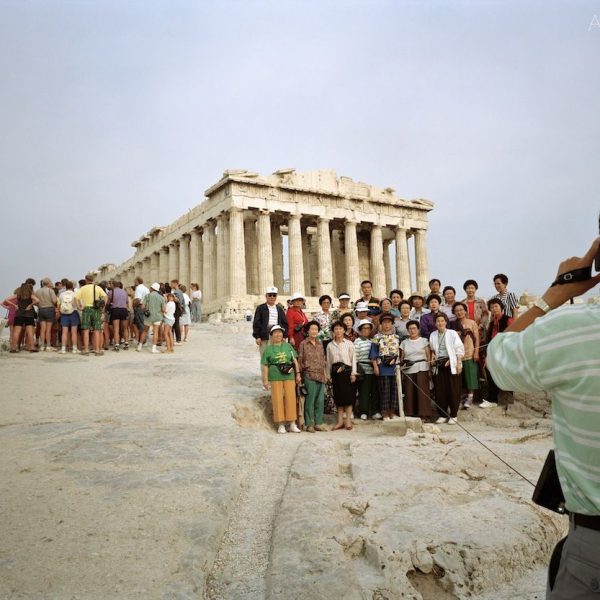

Dyer writes, “People go to places not to see the places but to obtain evidence – photographs of themselves – of having been there. Martin Parr takes things a logical stage further: photographing people being photographed and taking photographs.”

傑夫寫道:”人們旅遊的真正樂趣不在於旅遊本身,而是製造證據——為自己拍照——證明自己到此一遊。比起普通的圖片,帕爾的圖片在邏輯上更深一層:拍攝那些正在拍照的人。”

From the earliest photographs of the Egyptian pyramids by Francis Frith in 1856 to a world where “one no longer has to travel to Egypt to experience the Orient; it can be found in Las Vegas, in the shape of the Luxor”, Dyer reveals a world that we recognise but have never seen.

從1856年最早通過弗朗西斯·弗裡斯(Francis Frith)的照片窺探埃及的金字塔,“到現在人們

想體驗東方文化去拉斯維加斯一趟就行,那裡也有盧克索(Luxor)的金字塔。“戴爾揭示了一個我們知道但沒有真正看到的世界。

We are pleased to introduce for the first time to Chinese readers the English writer, Geoff Dyer. ‘Small World’ has been translated by Yu Chang.

我們很高興通過于暢為《小世界》作的翻譯來向中國讀者介紹英國作家傑夫·戴爾。

———————————————————————————————————————

The tradition of photographing exotic places reaches back almost to the invention of the medium. As the Grand Tour was extended to take in ‘the Orient’ so, in the 1850s, photographers such as Francis Frith lugged their bulky equipment to the eastern Mediterranean and beyond. Once the resulting pictures of the pyramids and other wonders became widely available the desire to go to these places increased. Such was – such is – the allure and promise of photographs that people wanted to see the precise spots show in the pictures. Part of the motive for traveling was, as it were, to experience the photographs on site, for real. Of course there was a lot to see that hadn’t been photographed, but the places in the frame served as oases or taverns, nodes that visibly determined one’s itinerary. Adventurous travelers naturally wanted to get off this pre-beaten track. By so doing, the places they visited gradually became part of the track. Just as Wordsworth complained about the growing numbers of visitors to the Lake District that his poetry had attracted so travelers to out-of-the-way places began to lament the tourists that came after them.

As travelling has become quicker, easier and cheaper so this problem –or syndrome – has grown more acute. Whereas it once required a considerable effort of will and some ingenuity to get to Egypt, Paul Fussell, in his book Abroad, thinks that the coming of efficient, uniform jet travel- which ‘began in earnest around 1957’-‘represents an interesting moment in the history of human passivity’. Maybe so but, as Garry Winogrand’s airport photographs from the 1960s and ’70 attest, it also heralded a great democratic expansion of the opportunity horizon.

The pictures in Martin Parr’s Small world both sum up this contradictory history and depict what might turn out to be its terminal phase. They show the places photographed by the likes of Frith (the pyramids) and they show how the excitement and promise of Winogrand’s pictures has become a source of cramped frustration. When I was seven, in 1965, my parents and I went to London for a week’s holiday. One day, as part of this vacation, we took the Tube out to Heathrow, not to fly somewhere, just to see the airport. For us it was not a place of departure but a tourist destination in its own right. With the inconvenience of air travel drastically increased in the wake of 9/11 the average traveler – i.e. anyone not in Business or First- dreads going to the airport. To add insult to injury- or, more exactly, guilt to discomfort- we are now acutely conscious of the cost to the environment, of the way that air travel is contributing to global warming. In this context a stay-at-home like Fernando Pessoa seems almost visionary:’ What is travel and what use is it? All sunsets are sunsets; there is no need to go and see one in Constantinople.’

It’s not just the sunsets. When people do travel to Constantinople- or anywhere else for that matter- they can increasingly expect to find many of the things and conveniences taken for granted at home. Back in the 1950s the Swiss tourist Robert Frank traveled through America photographing ‘the kind of civilization born here and spreading everywhere’. Frank was right: forty years down the line Parr finds bits and pieces of the American imperium everywhere. (He also records the contrary tendency whereby one no longer has to travel to Egypt- with the attendant threat of terror- to experience the Orient; it can be found in Las Vegas, in the shape of the Luxor.) In order to escape the tentacles of this homogenizing ‘civilisation’ it is necessary to travel further and further afield. And by so doing you drag those tentacles after you. We are all responsible for the ruination we lament. Wherever you travel some kind of industry develops to cater for you –even if it’s not the kind of catering you, personally, were hoping for. A couple of years ago my wife and I traveled to Jaisalmer in the desert of Rajasthan, a place she remembered as being almost Calvino-esque in its isolated beauty. In the decade since her first visit, however, it had been incrementally trashed. With every bled nothing else so much as a fortified reincarnation of Camden market. In a cruel twist to the familiar story of how the indigenous people of a place (‘Indians’ as they were referred to throughout the Americas) traded the wealth of their land for a few worthless trinkets, the people of Jaisalmer, having put their heritage in hock, were left selling worthless trinkets that no one wanted- and, as a result, we, the tourists, felt cheated by the commerce that had sprung up to pander to us.

The effects of tourism are, of course, not uniform. Not all places have given themselves over entirely to tourism. But, as Mary McCarthy wrote almost half a century ago, ‘there is no use pretending that the tourist Venice is not the real Venice, which is possible with other cities- Rome or Florence or Naples. The tourist Venice is Venice…Venice is a folding picture-post-card of itself’.

Venice is an extreme case. Even in Rome or Florence, however, visitors feel reassured by the way there are so many others doing, seeing- and photographing – the same things. Off- putting to some, a restaurant offering a ‘Tourist Menu’ is tempting to many. At the risk of being racist, the Japanese- the ‘lens-faced Japanese’. In Martin Amis’ phrase- seem to take particular comfort in being photographed places not to see the places but to obtain evidence – photographs of themselves – of having been there. (Actually, this argument has been rehearsed so many times that it’s a negative version of the same tendency. By making the point I am effectively making a record of myself standing in front of a cultural edifice signifying superior worth and discernment.)

Parr takes things a logical stage further: photographing people being photographed and taking photographs. In this respect the Small World pictures stand comparison with the large-scale images by Thomas Struth, in which we look at visitors looking at famous works of art (which, lest we forget, are also tourist attractions). The difference is that whereas in Struth’s photographs that greatness- or aura or whatever you want to call it- of these artworks survives the process of mediation, in Parr’s ‘place’ and visitor work to their mutual diminution. Tacitly- or maybe not even tacitly – he endorses the verdict of the narrator in Don DeLillo’s The Names:

“Tourism is the march of stupidity. You’re expected to be stupid. The entire mechanism of the host country is geared to travelers acting stupidly. You walk around dazed, squinting into fold-out maps. You don’t know how to talk to people, how to get anywhere, what the money means, what time it is, what to eat or how to eat it. Being stupid is the pattern, the level and the norm.

Like DeLillo, Parr is not scathing or moralistic about this perceived failing. He enjoys it too much for that. There’s too much mileage in it.

It is as hard for photographers to be funny as it is for a critic to explain a joke (this probably has something to do with the medium’s defining quality of reproducibility; how many jokes can withstand infinite repetition?) but they can be witty. The wittiest photographer was Henri Cartier- Bresson (with Winogrand a close second), who, if he had worked in colour, might have relied on some of the same devices as Parr. Ironically, it was at the opening of Small World in Paris in 1995 that Cartier-Bresson told Parr that he must be ‘from a different planet’. One sees what he means but one also sees that, at some point in their orbits, their two planets are thrown into unexpected alignment. In the random accidents of colour Parr contrives to find a version of the rhymes and puns that Cartier-Bresson discovered in the fleeting symmetries of pictorial geometry.

Are Parr’s visual jokes at the expense of the people depicted? Is he fair? In the context of a world in which war photographers are snatching images of death maiming, grief and suffering Parr’s trespasses are easily forgiven. (Having mentioned war it’s worth remembering that, since Parr works in some of the most intensively photographed spots on earth, he can probably claim immunity on the grounds that they are, to use a phrase from Vietnam, free-fire zones.) I suspect, also, that the people in the photographs would recognize themselves and their fellow travelers. They would agree that, although they have chosen and paid to come to these places, sightseeing in particular and holidaying generally are often the opposite of fun- partly because of all the other tourists. (Like car drivers moaning about traffic, the disceming tourist often complains that a place is ‘too touristy’.) And the money, even in supposedly cheap places, slips through your fingers like water. Forty years on, my father is still traumatized by the extraordinary price of the choc-ice we almost bought outside Madame Tussaud’s during that trip to London. In this respect he has something in common with D.H. Lawrence, who, in Sea and Sardinia, is in a state of constant fury about being overcharged: ‘I am thoroughly sick to death of the sound of liras…Liras –liras-liras- nothing else. Romantic, poetic cypress-and-orange-tree Italy is gone. Remains an Italy smothered in the filthy smother of innumerable lira notes: ragged, unsavoury paper money so thick upon the air that one breathes it like some greasy fog.’

There is no way round it: to travel, either as backpacker or package tourist, is to be forced into being an incessant consumer. Factor in queues, hassle, jetlag and tummy upsets and it’s a wonder, even now, when travel has become so easy, that people still want to do it. Philip Larkin certainly didn’t want to, but he did consent, every year, to take his mother away for a dismal week somewhere in England (he didn’t believe in ‘abroad’). The experience led him to develop ‘a theory [that] “holidays” evolved from the medieval pilgrimage, and are essentially a kind of penance for being so happy and comfortable in one’s daily life’.

That’s what the pictures in Small World depict: the form and state of modern, faithless pilgrimage. I think, next year, I might try Mecca.

Geoff Dyer (photo : Matt Stuart)

Geoff Dyer was born in Cheltenham, England, in 1958. He was educated at the local Grammar School and Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Geoff lives in London.

He is the author of four novels: Paris Trance, The Search, The Colour of Memory, and, most recently, Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi; a critical study of John Berger, Ways of Telling; two collections of essays, Anglo-English Attitudes and Working the Room; and five genre-defying titles: But Beautiful, The Missing of the Somme, Out of Sheer Rage, Yoga For People Who Can’t Be Bothered To Do It, and The Ongoing Moment. He is the editor of John Berger: Selected Essays and co-editor, with Margaret Sartor, of What Was True: The Photographs and Notebooks of William Gedney.

A selection of essays from Anglo-English Attitudes and Working the Room entitled Otherwise Known as the Human Condition was published in the US in April 2011 and won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism.

His most recent book is Zona, about Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker (published in the UK and the US in Spring 2012).

Geoff Dyer was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2005.

馬丁·帕爾的《小世界》Martin Parr’s Small World

獵奇是攝影界一貫的傳統,這一傳統幾乎可以追溯到攝影機問世之初。在周遊歐洲大陸之後,早期攝影家們又把目光瞄準了“東方”。自19世紀50年代以來,弗朗西斯·弗裡斯(Francis Frith)等一批攝影家相繼拖着笨重的攝影機器,遠涉重洋,奔赴地中海西岸,乃至更遠的地方。就這樣,金字塔等各種異國風情的照片在歐洲漸漸流行開來,大大刺激了人們出行的慾望。這便是攝影的無窮吸引力和魅力所在——召喚人們身臨其境去感受一番。當然,人們去旅遊的動機不僅限於此。雖說照片捕捉到的僅僅是冰山一角,但這些景觀卻能在很大程度上左右遊客的行程,似沙漠中的綠洲,又似長途跋涉中遇到的客棧,引導人們不斷地去探索,去發現。相對於普通的旅遊者,那些喜歡探險的旅遊者則更願意到人煙稀少的地方去旅遊。然而當越來越多的人開始踏進這些原本不為人知的地方時,這些地方也就不可避免地會變成旅遊景點。華茲華斯(Wordsworth)的田園詩歌吸引了大批遊客到湖區遊玩,然而他對卻對此相當不滿,認為遊客的到來破壞了湖區的寧靜。同他一樣,探險旅遊者也對接踵而至追隨他們足跡的遊客頗有微詞,殊不知,他們自己才是破壞原始生態和人文環境的始作俑者。

當旅遊變得越來越便捷、輕鬆和廉價時,環境問題——或者我們可以稱之為旅遊綜合徵——也就變得越來越嚴峻。不僅是環境問題,過去,只有那些熱衷冒險又富有智慧的人才敢去埃及旅行,保羅·法瑟爾(Paul Fussell)在《去國外(Abroad)》一書中認為這樣高效率和模式化的飛機旅遊時代的到來——大約始於1957——是人類歷史上一個有趣的時刻,標誌著人類從主動旅遊向被動旅遊的轉變。他的說法可能有一定的合理性,但不可否認,飛機的確給人們的出行帶來了極大的便捷,正如蓋瑞·溫諾格蘭德(Garry Winogrand)六七十年代的機場系列攝影作品所展示的那樣,飛機旅遊時代的到來,大大增加了人們出門旅遊的機會,極大地擴展了他們的視野。

馬丁·帕爾的《小世界》攝影系列既對旅遊業發展給人類帶來的雙重影響進行了總結,又對其未來發展前景進行了探討。當中涉及的有些地方弗西斯等人以前也拍過(例如金字塔),但這些地方最終沒有像溫諾格蘭德那樣給人帶來興奮,而卻都變成了讓人失望而回的地方。記得那是1965年,父母帶著年僅七歲的我去倫敦一週游。期間有一天我們專門乘地鐵去希思羅機場參觀,我們並不是乘飛機出發去哪裡,只是純粹去看希思羅機場。對我們而言,機場不單單是一個送別親人朋友的地方,其本身就是個旅遊景點。9.11事件後,普通出行者(商務艙或頭等艙乘客除外)的航空旅遊受到了極大的限制,更雪上加霜的是——確切的說,是更讓我們有負罪感的是——我們越來越清楚地認識到了發展旅遊業對生態環境造成的破壞,航空旅遊勢必會加劇全球變暖。這樣看來費爾南多·佩索阿(Fernando Pessoa)選擇呆在家裡哪兒也不去似乎是相當明智的:“究竟什麼是旅遊?旅遊有什麼用?哪裡的日落還不都是一樣的?何苦非要跑到君士坦丁堡去看日落呢?”

旅遊當然不僅僅是為了去看日落。如果你去君士坦丁堡看日落——或是別的地方也好——你就會發現那裡的一切都和家裡是如此的不同。20世紀50年代,瑞士旅遊家羅伯特·弗蘭克(Robert Frank)遊歷美洲大陸,旨在記錄“美國文明的誕生及其向全球的傳播。”弗蘭克的想法是對的:在長達40年的攝影生涯中,帕爾也對這一現象深有體會,美國的資本主義文明幾乎已經遍及全球的各個角落。(他的作品在這裡不再是鼓勵人們出行,恰恰相反,他認為我們完全沒必要非去埃及旅遊——還得提心吊膽地怕遇上恐怖襲擊——目的僅僅是為了感受東方文化;想體驗東方文化去拉斯維加斯一趟就行,那裡也有盧克索(Luxor)的金字塔。要想擺脫這種千篇一律的全球化景象,尋求不一樣的體驗,我們就得去更遠的地方。

我們在感慨原始文明的被破壞時往往忘了,其實我們人類自己才是這些破壞的罪魁禍首。無論你是去哪裡旅遊,那裡總會有各種各樣的服務在等着你——即使有些並不太符合你個人的需求。幾年前我同妻子去齋沙默爾(Jaisalmer)(位於拉賈斯坦邦沙漠Rajasthan)旅遊,妻子說這個地方像卡爾維諾(Calvino)式的具有與世隔絶的曠世之美,令她難以忘懷。然而僅僅10年以後,齋沙默爾竟變得面目全非了。空氣中到處瀰漫的是銅臭味,活脫脫一個卡姆登集市(Camden market)的翻版。正如原始印第安人會用土地換取其他部落的廉價首飾那樣,齋沙默爾人把自己寶貴的文化棄如敝屣,反而去追求那些毫無價值的庸俗之物——因而作為遊客,我們有種被欺騙的感覺。

當然,並不是所有的旅遊景點都像齋沙默爾那樣徹底地商業化和旅遊化。但正如瑪麗·麥卡錫(Mary McCarthy)在將近一個世紀之前寫的那樣:“我們不能說旅遊化的威尼斯就不是真正的威尼斯了,其他旅遊城市——羅馬、佛羅倫薩、那不勒斯也是一樣。旅遊化的威尼斯才是真正的威尼斯……威尼斯本身就像明信片裡那樣多姿多彩,引人入勝。”

威尼斯也許是一個極端的例子。在羅馬或佛羅倫薩,遊客大概會感到安慰,因為很多人跟自己一樣做著同樣的事,觀光、拍照等等。令人懊惱的是,一餐館專門推出 “遊客菜單”但卻大受歡迎。冒著被指責為種族歧視者的危險,馬丁·埃米斯(Martin Amis)戲謔地稱日本人為“照相狂日本佬”。用他的話來說——日本遊客對拍照的熱情令人咂舌,他們旅遊的真正樂趣不在於旅遊本身,而是製造證據——為自己拍照——證明自己到此一遊。(這麼說,我似乎又把我自己放到了一個文化制高點,以優越的價值觀和洞察力自居,去批判他國文化了)。

比起普通的圖片,帕爾的圖片在邏輯上更深一層:拍攝那些正在拍照的人。在這一點上,《小世界》系列和托馬斯·斯特魯斯(Thomas Struth)的大畫幅系列可以一比,我們通過斯特魯斯的圖片看遊客的同時他們也在看名畫(我們往往忽略了,其實這樣滿是遊客的場景也是景點的一部分)。兩者所不同的是,那些名畫的偉大和光環在冥思過程中還能幸存,但是在帕爾照片裡 “地點”和“遊客”的組合卻只能互相貶值。我們可以說帕爾用的是隱晦的方式表達他的思想——或者說是較為溫和的方式——他對唐·德里羅(Don DeLillo)在《名人們(The Names)》 中的觀點極為推崇:

旅遊就是變成傻瓜的過程。別人希望你是傻瓜。東道國的一切都是為傻瓜遊客量身定做的。在這裡你會茫然地到處瞎逛,眯着眼睛吃力地看地圖。你不知道如何跟人當地人打交道,你不知道路線,不知道你的錢在這裡能買多少東西,你不知道該吃什麼、怎麼吃,甚至不知道時間。變傻瓜就是旅遊的模式、標準和常態。

同德里羅一樣,帕爾對這種變成傻瓜的過程是相當享受,既沒有感覺到受傷,也沒有從道德上對之進行批判。他愛死旅遊了,他能從這個過程中獲得很大的快感。

讓批評家去解釋笑話是很困難的,同樣,我們也不能奢望讓攝影師去逗樂觀眾(這可能與圖片的可複製性有關;試想,有多少笑話能經得住無限的重複?)但攝影師可以很有趣。世界上最有趣的攝影師應該是亨利· 布列松·卡蒂埃(Henri Cartier-Bresson)(溫諾格蘭德稍遜於他),他如果嘗試彩照的話,大概也會用到一些同帕爾類似的策略吧。然而具有諷刺意味的是,在1995年巴黎舉行的《小世界》系列的首次展覽會上,卡蒂埃·布列松對帕爾說了一句這樣的話“你一定是從另一個星球來的”。通過觀察二人的作品我們不難發現,布勒松和帕爾這兩個來自“兩個星球”的攝影師在某些方面有着驚人的一致。帕爾從看似隨機的色彩選擇中發現了如何表達韻律和雙關意義的方法,而布列松則用圖片的幾何結構將這些意義表達了出來。

帕爾攝影的成功是建立在諷刺照片中人物的基礎之上的嗎?這樣做合理嗎?想想戰地記者們常發回的那些專門捕捉死亡、殘廢和人在水深火熱裡掙扎之類的特寫,帕爾的小嘲諷往往會被忽略(說起戰爭,可別忘了,帕爾工作的地方都是一些廣為人知的景點,也就是越南人所說的停火區,他是享有豁免權的)那些有幸被拍進照片的人在看到這些照片時會一眼認出他們自己吧。雖然他們是自願花錢出來的,但觀光也好——或就整個旅遊活動來說,有時候並非是一種享受——而是受罪——一定程度上是由於其他遊客的存在(正如司機會抱怨堵車一樣,敏感的遊客也常常會發牢騷“這個地方遊客太多了”)。還有就是旅遊花費了,即使你去相對廉價的景點,也難免花錢如流水。雖都過去快40年了,但我父親至今仍然對杜莎夫人蠟像館門口那昂貴的巧克力脆皮雪糕耿耿於懷,當時差點就忍痛買了。就這點來說,父親同戴維·赫伯特·勞倫斯(D.H. Lawrence)挺像的,後者在《大海與撒丁島(Sea and Sardinia)》一書中對(旅遊時)被宰憤怒不已——“我討厭死里拉(liras,意大利貨幣)這個詞了。到處聽到的都是里拉——里拉——里拉——除此之外就沒有別的。那個到處是柏樹和橘樹,浪漫又詩意的意大利已經不復存在了。意大利快被里拉堵窒息了:破爛、倒人胃口的錢發出濃重的骯髒氣味,像油膩的煙一樣難聞。”

你別無選擇:無論是自助旅遊還是跟團旅遊,只要你是去旅遊,就得不停地掏腰包。說來也怪,旅行中常常會碰到的譬如排長隊、倒時差、噁心反胃等麻煩似乎絲毫阻擋不了人們出行的熱情。菲利普·拉金(Philip Larkin,英國現代詩人)對旅遊並不見得有多喜歡,但他卻會每年帶著母親去英格蘭度假一週(他對“國外”景點不大信任)。由此他提出一種新的理論,他認為“度假”是從中世紀的朝聖演變而來的,由於平日裡的生活過於幸福和舒適,人們選擇“度假”以作為一種贖罪。

這就是《小世界》圖片裡所呈現的現代社會形態: 旅遊——一種沒有信仰的朝聖苦旅。或許,明年我真的可以考慮去麥加看看。

作家簡介:

傑夫·戴爾,1958年生於英格蘭切爾滕納姆(Cheltenham),曾就讀當地文法學校及牛津大學聖體學院(Corpus Christi College),現居倫敦。

傑夫共撰寫過四部小說,包括Paris Trance、 The Search、 The Colour of Memory,、Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanas。他亦出版過關於John Berger的評論研究Ways of Telling, 兩本論文集Anglo-English Attitudes和Working the Room,五本反流派書籍But Beautiful, The Missing of the Somme, Out of Sheer Rage, Yoga For People Who Can’t Be Bothered To Do It和 The Ongoing Moment。他也編寫了John Berger:Selected Essays,與Margaret Sartor合編了What Was True: The Photographs and Notebooks of William Gedney.

Anglo-English Attitudes論文集中的選登論文和Working the Room裡的Otherwise Known as the Human Condition在2011年4月於美國發表,並獲得國家書評獎(National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism)。

他最新作品 Zona於2012年春天在英國及美國出版, 書中講述的是Andrei Tarkovsky的電影 Stalker(潛行者,攝於1979年)。

傑夫在2005年被選為英國皇家文學學會的會員。