Preface

The fragmentary essay below does not aspire to render a contextual study of the painter in ways that are structurally adequate to the task of synthesising its findings within other more comparative findings. Rather it is attempts to constitute its object as being spectrally other in that the text posits a final fold within an imaginary construction after the death of the artist. There is within this a semblance not just of the drama of death (of history, art, and the subject) but another form of after life, even if touched by a delirium of sense.

前言

以下的短文並不旨在從一個完整的角度深入探討這位畫家,或是希望能將其發現與其他比較研究結合來呈現對藝術家的背景研究。相反,本文試圖在藝術家逝世後探討他的畫作作為一種獨特存在的意義。這其中不只揭示了死亡的戲劇性(包括歷史、藝術和主體的死亡),還暗示了死後的另一種生命形式,即使這種生命帶有某種迷亂的感覺。

Painting, Smoking, Eating” (1973)

In the work “Painting, Smoking, Eating” (1973) there are three occurrences, smoking that is happening, painting that has happened, and eating which will happen. The question posed by the painting is, are these successive actions and as such are they linked in a repetition-compulsion chain? The scene is weighted by something that is rendered outside of this chain, and that is sleeping, which does not occur readily but is rather a source of incessant anxiety. There is no way out of this murmur of what is incessant that is founded on the contrary of ethical pain and aesthetic pleasure.

The Zen monk Dogen (1*) once said that humans could hear through their eyes. Dogen invites a view of reality in which logical, dualistic sense is thrown asunder. This holds a poetic mode of resemblance to the working of (non) sense in the late paintings of Philip Guston.

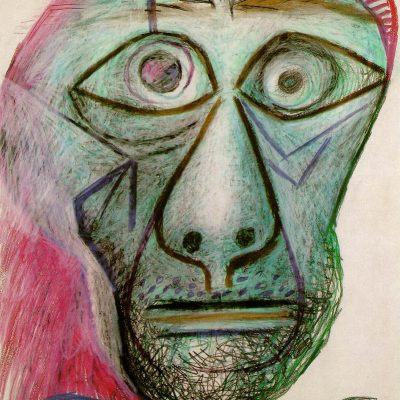

Faces depicted in Guston’s paintings invariably have eyes that are like bulging eruptions of tissue facing the world. Other sensory organs, or even sensory passages, seem to be either absent or diminished. These heads are perhaps more like witnessing outposts, framed within an immobile gaze that is cast away from the very moorings that might in turn provide a sense of having a world. Could it be that the eye is being figured as the last refuge of a subject adrift from the indexes that constitute it? Philosophically the history of the Western metaphysical tradition can be viewed as a construction of meaning through the notion of presence and with this a relationship to ocular metaphor (to see, is to know). The subject is constructed as a spatializing entity, drawing lines, constituting limits, in ways that privilege the ocular capacity within philosophical discourse. Language in turn becomes embedded within the metaphors provided by this process. Guston appears to create a double reflex or gesture in the relationship to this privileging of the eye over the other sensory organs. In exaggerating the visual sign of the eye, Guston extends the immanent logic of this sign, to push it to a threshold that isolates the orbit of its constitution; he appears thus to diminish its power. The exaggerated depiction of the eye draws the viewer into the eyes isolating impotence because it lacks a world in which it might delight or wonder. Also, these are paintings that also appear to signify the loss of eye; they are bad paintings in the sense that they represent, without the adequate capacity for doing so. Somehow the very loss of capacity both to see, and in turn to paint, isolate these paintings from a possibility of framing the dimension of history, because the visual field that touches the extended space of history is out of reach. History has become a passing over and through in which subjects are cast adrift as mere vestiges (2*).

Bereft of the tissues of narrative strands, these late paintings appear to be immersed within the feeling of empty time. Empty time in this context might be understood as a texture or a weight that pulls on things and slows them in such a way that lends a stagnancy of matter and dulls all things that are held within the frame. Emptiness thus circulates and clings to all the surfaces that are touched, becoming a form of sticky equivalence that connects all things. Substances congeal, assuming in turn blob like characteristics, and with this the air seems to thicken with bodies that appear to be held in poses close to states of slumber. The atmosphere relating to entropy accrues, thus buns are sticky, paint, leaded and creamy, sight is trapped in monotony, and backgrounds slighted by a forgetting of detail. These paintings appear to move only by virtue of emerging within the medium that describes them, and yet within their own medium nothing appears to happen, and even if something appears to happen, it leads back to the nothing from which it emerged. There is, of course signs of duration, but only to the extent to secure the ever- open of eyes deemed incapable of blinking, that might in turn, interrupt the stagnant ready-at-hand heavy present. For a moment we could start to imagine that these paintings are sites of a dialectical critique of the society of mass consumption, with all its pristine shine, sharply defined edges and surfaces, its smooth persuasion in positioning things, the glamorous cynicism, hyper-pulsation within its orbits and style, but the space that might contain all of these facets will also be the sign of this otherness that has already been subsumed in an after-world which is set in the boredom of its deliberation. What we are witnessing is a point beyond critique, in the form of a series of inscriptions that are recorded within bodies and things that have been pressed or pushed through this world. These bodies are presented as being alert only to the tiring rhythm of empty ambition, polluted by cigarettes, lured, and fattened by French fries, deprived of the sleep that clear conscience might secure, with hearts weakened by stress, becoming instead a buried darkness of the floating signifiers of a promise held above. They are bodies rendered foreign in their own constitution, holding in their dark reserve, projections of signs that can only articulate exhaustion. We might see the body as a dead weight being dragged through the plane of the canvas in order that it might soak up, in the manner of a sponge soaking in a cloud of turpentine vapour. Such bodies do not serve as vehicles of resurrected promise, but rather in a half-paced manner, they continue without hope of reply, and it is this sense of lack that lends a feeling of authenticity to the situation that contains the action, or orientation towards the immediate horizon. A mood of being already dead prevails, or at least the sense that each possible horizon is impregnated with death, and it is this that marks all conditions of knowing and acting.

Asked about what was at the root of his late paintings, he simply uttered the word “doomed”. This single word appeared to contain an excess of different possible senses. The paintings are born out of an impulse to speak but are also rendered bereft of the capacity to do so. As paintings they appear to simply endure a world under the sign of extinction, the death of the subject, the end of history, media saturation and exhaustion. They are fugitive paintings in which traces of the world persist but without sense of destination. Watches and clocks appear to mark out the stagnant air with monotony, simply turning over in an empty version of time. In presenting a universe in which remoteness or inertia come to dominate, there is no possibility of a process of reflection figuring an agency of decision. The fat of the world thus accrues in the face of this lost vitality. Things are abandoned without the trace of their original signature; they pile up, or are left undone, consumption is unattended, bodies appear as indifferent, or idle, and even the lights are not switched off. Only addictive or dumb acts stay in some register of reality, but these are held as repetitions or compulsions that record forms of circular tracings as just another mode of stasis. What is being attempted here is to probe the way in which proximity and distance appear as kinetically welded to a subject, whose very orientation appears to be cast adrift in contradiction to such forces. We are given renderings of scenes, in which looks are in circulation, that also contain active criss-crossing of circuits of desire, in which muscles arch and tense in order to be able to be viewed and to view, and with this a negation of a positive virility of spatial articulation, that Guston wishes only to slow to the point of immobility. In this state of immobility, we are drawn to the weight of the paint, that almost seems to stand for the burden endured by the subject. Is it not the substance of paint that sticks things together, serving as an essential glue of this world, paint that is also the source of mobility that lends signature to all things touched and caressed, in all these respects Guston directs us toward paint as a vanishing point of the labour process. All things lost or abandoned, are recuperated by and within the materiality of paint, with all of its insistence of registration and sensual presence.

Paint is the only redress to ruination that can be offered as redemption. This makes me wonder about his earlier period that is designated as Abstract Expressionist. Having seen the cycle of his work, it might be imagined that he could have returned again to this idiom but in a darker palette as if to carry forward a mood that is not accessible through naming. Just like a poet whose dependency on the pure word, there is a shine that is accessible through gesture that touches on withdrawal. This withdrawal of direct speech might have signified an endurance of no longer being able to communicate with the employment of indexical markings. Such an approach to the night-time of art would have attested to the possibility of a midnight condition of no longer being able to go either backwards or forwards, thus being alone in a state of suspension with only paint marks being offered as testament.

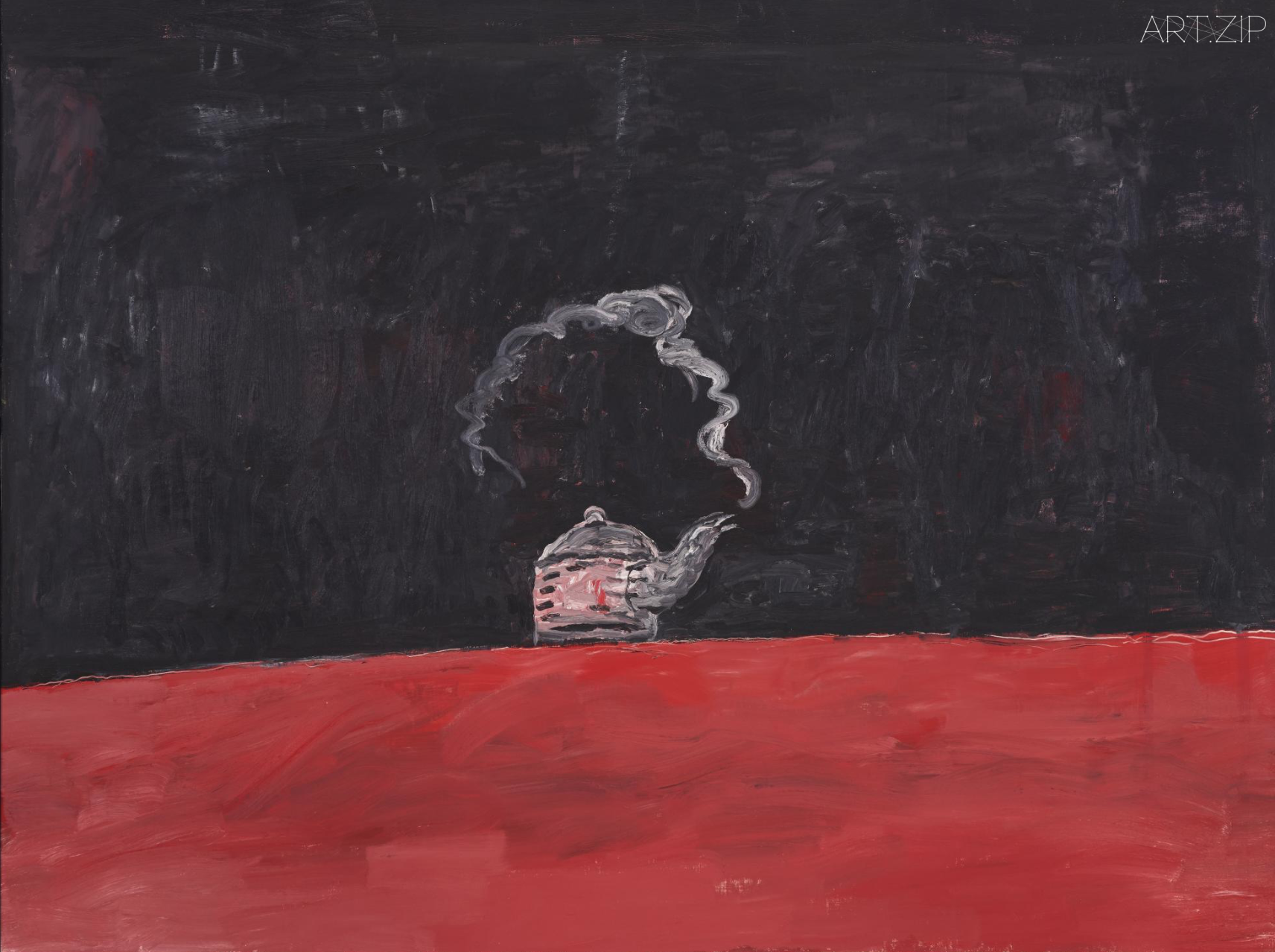

Such an idea of a final shift opens a dialogue with late Goya’s black paintings (3*). What lies beyond such a dialogue, is the possible dissolution of the kettle (4*) boiling in blackened space leaving instead just the swirl of vapour within darkness. Thus, a presentation of a condition of painting that is neither purely serene nor singularly desperate, but beyond such contraries: painting that speaks without recall to the conditions of having a language to do so. This would be a presentation that no longer rests on an unresolvable tension between figuration and abstraction but rather is a third genus beyond such opposition, with pink, black and green or the spiritual and the secular in free play within a zone that is but a steppingstone towards the immeasurable.

Something looks back, even if the gaze is dark, for no matter what intensity of blackness, the shining contained within difference still becomes manifest. At the threshold of visibility, figures of radiance and resistance are joined together within the diagram of becoming. Within this diagram, there is Goya’s painting of ‘The Dog’ (1819-1823), Picasso’s ‘Self Portrait Facing Death’ (1972), and Guston’s ‘Kettle’ (1978). All three paintings present figures alone in space, dramas of dissolution staged at the limits of experience. Why do these paintings meet up in this space? Already the staging has started to assume a spectral otherness, a halfway meeting place between the virtual and the real, and with this life and death. Is not lateness always marked by such signage and with this a feeling of delirium? So not only the mixing of three paintings, but a halfway narrative mixing the spectral, virtual, and the real. If then other paintings start to be figured as immanent projections of the after life of these works bereft of authorship, what then? Clearly this is just a fictionalised projection, a sign of a boundary crossing, or a doubling of the represented real with the impossible excess. Is not this crossing over of boundaries a transgression of the disciplines that keeps everything in place, subjects pressed under, objects leaning against, lines drawn between such conditions? All of this might serve to return us to the insight of the priest-poet Dogen when he stated that humans can hear through their eyes. Imagine a space of painting predicated upon such logic. Surely a stepping stone into immeasurability.

在作品《繪畫、抽煙、吃飯 》(1973)中,我們可以看到三個階段的行為:進行中的抽菸,已經完成的繪畫,和即將開始的進食。這幅畫引發了對動作連續性的質疑:這些行為真的構成了一個不斷重複的強迫性循環嗎?但場景中有一個重要的元素,那就是睡眠,它並沒有直接出現,而是成為了源源不絕的焦慮。這種無休止的焦慮與道德上的痛苦和美學上的愉悅形成了對比。

道元禪師(1*)曾提出,人的眼睛具備聆聽之能。道元的這一觀點打破了傳統的二元邏輯,向我們開啟了一種全新的理解現實的途徑。這與古斯頓晚期畫作中的(不)合理操作有著詩意的相似。

古斯頓的畫作中描繪的臉部總是有像突出組織一樣的眼睛,盯著這個世界。其他感覺器官或甚至是感官通道似乎都被忽略或弱化了。這些頭部更像是目擊者的前哨,被框定在一個固定不動的凝視之中,遠離了可能給予它有世界感的支柱。難道眼睛已成為迷失方向的自我尋找依歸的最後棲所?從哲學的角度,西方形而上學的傳統可以被看作是通過存在的觀念構建意義,與此相伴的是與視覺隱喻的關係——“看”就是“知道”。主體被構建為一種具有空間化特性的實體,劃定線條,確立界限,這種方式在哲學話語中賦予了視覺能力特權。語言深深植根於這些透過視覺概念所繪制的哲學意象之中。古斯頓似乎在強調這種眼睛視覺感官超越其他感官的特權關係中創建了一種雙重反射或姿態。通過誇大眼睛的圖像,古斯頓進一步深化了這一符號的本質含義,將其推至一個新境界。在這個境界中,眼睛被剝離了其固有的軌跡,好像在此過程中,其原有的影響力也隨之降低。這種誇張的眼睛描繪,將觀者吸引進一個孤立無援的視界,因為它缺乏一個可能帶來愉悅或驚奇的世界。這些畫似乎傳達了視覺的消逝;它們在某種意義上是失敗的畫作,因為它們試圖表達卻顯得力不從心。這樣的喪失,無論是對看見的能力還是對繪畫的掌控,將這些畫作與可能書寫的歷史維度隔絕開來,因為能連接到歷史的視角已經消失。歷史已成為一場過眼雲煙,當中的主體(人)如同飄散的殘影,被世界拋棄(2*)。

這些晚期畫作缺乏了敘事的細節與連結,讓人感到它們正浮游於一種無內容、空洞的時光之中。這種“空洞的時光”賦予了一種沉重感,仿佛是不可見的手牽引著事物,讓它們在無聲中放慢腳步,一切都沉浸在靜止的氛圍中,失去了往日的光彩和活力。空虛似乎在每一處潛伏,讓接觸到的每個事物都被同一種沉重的氣息所覆蓋,彼此間仿佛被一種無形的粘合力緊密相連。在這些畫作中,各種物質彷彿停滯凝固,空氣似乎也因此變得濃稠,其中的身體彷彿被定格在接近沉睡狀態的姿勢中。在這樣的場景中,無序的增加使得每一個物體似乎都被黏稠和沉重所束縛。面包變得黏手,顏料厚重得像奶油,視覺陷入一成不變的單調,而背景也失去了細節。這些畫中物看似在其所處的媒介中慢慢有了動態,但本質上自身卻仍靜止不動,任何看似發生的變化最終也都逃不脫那最初的空無感,彷彿一切都是從無到有,又從有回歸無的循環。畫中似乎流露出一種時間的綿延,但這只是為了展示那些永恆張開、似乎失去了眨眼功能的眼睛,正是這種狀態阻斷了對那種沉甸甸、一成不變的現實的任何打擾。我們可以短暫地想象這些畫作是對大眾消費社會進行辯證批評的場所,這個社會的一切擁有著無瑕的光澤、清晰定義的邊緣和表面,事物被巧妙安排,以流光溢彩的魅力和玩世不恭塑造出一種獨特的風格。但即使這些元素都凝聚於畫布之上,它們最終也只是成為了一個更加深層的「他者」的象徵,一種在冗長無趣的反思中被消融的存在。我們目睹的是一種批評之外的一種獨特印記,記錄著那些在世上曾被壓迫、被推拉的身軀和事物。這些描繪的身體似乎只對無益的渴望有反應,被香菸所污染,被薯條所誘惑並發胖,失去了良知帶來的安寧睡眠,心臟因壓力而變得衰弱,最終沉淪於那些高懸未兌現承諾的空洞之中。這些身軀像是外來之物,只剩黯淡,成為了傳達深切疲弊的符號投射。畫中的身體就像是吸收松節油霧的海綿,在畫布上被拖著走,吸收著所有的重壓和疲憊。這些身體並不是承載著重生希望的載體,反而是以一種無望回應的半速狀態持續前進。正是這種空虛與失落,讓整個場景的動態和方向顯得更貼近真實。一股彷彿生命已經逝去的沉重氣氛瀰漫其中,好像所有可能的未來都被死亡的陰影所籠罩。畫中所呈現的不再是對生活的知覺和行動,而是一種絕對的缺乏和失落感。

當被問及他晚期畫作的根源時,他只簡單地吐露了一個詞:“註定失敗”。這一個詞似乎包含了太多可能的意義。这些画作诞生于一种表达的冲动之中,但又仿佛丧失了言语之力。作為畫作,它們似乎只是在一種消亡的徵兆下忍受著世界——主體的死亡、歷史的終結、藝術媒介的極度飽和和疲憊。這些畫是飄渺的,世界的蹤跡在其中殘留,卻又似乎迷失了方向。時鐘和鐘錶似乎用單調來標記著停滯的空氣,反覆輾轉於一種空洞的時間之中。在呈現一個遙遠或惰性主宰的宇宙中,不再有深思熟慮引領決策的可能性。在這種失去活力的狀況下,世界的沉悶感也不斷累積。這些物品被遺棄,失去了它們最初的特徵,無人理會地堆積起來,或是被遺忘在角落無人問津,人的身軀顯得無動於衷或無所事事,甚至連燈也沒有關掉。只有上癮或愚蠢的行為在現實中留下痕跡,但這些只不過是重複或強迫的記錄,它們形成一種循環的軌跡,成為另一種靜止不變的模式。這裡所嘗試探討的是,主體與近與遠的關係如何呈現出一種動態的緊密聯繫,即使這個主體的存在似乎在與這些力量的矛盾中漂泊不定。我們看到的是一幕幕場景的描繪,在這些場景中,視線在流轉,也蘊含著慾望回路的積極交錯,在此之中,肌肉弓起並緊繃,為的是能夠被看見並去觀看;與此同時,這些場景也否定了空間表達中的積極生命力,古斯頓只希望將其放緩到完全不動的程度。在這種靜止狀態下,我們被畫中顏料的重量所吸引,這似乎象徵著主體所承受的重擔。顏料不僅是將這世界緊密聯繫的基本粘合劑,也是賦予一切被觸碰和撫摸事物特色的運動之源。在所有這些方面,古斯頓將我們的視線引向顏料,作為繪畫過程中消逝點的隱喻。

顏料成為了破敗世界的慰藉,它是對毀滅的一種彌補,帶來了救贖的可能。這引發了我對他早年那被標籤為抽象表現主義時期的好奇。觀察過他創作的演變,我們可以想像他或許會重返那個風格,但這次他選擇了更深沉的色調,似乎要表達一種難以言喻的內在情感。正如詩人對那些純淨詞句的偏愛,透過那些宛如抽離般的姿態,我們得以一瞥內心深處的閃光。放棄直接的語言表達可能意味著一種堅忍:不再倚賴明顯的指示符號來進行交流。這種對藝術的夜晚時刻的描繪或許揭示了一種深夜的境遇,那是一個既不能回到過去也無法邁向未來的停滯時刻,留下的只有畫面上的顏料印記,見證了這份孤獨與懸置。

對於藝術風格轉變的最終思考與戈雅晚期創作的黑色繪畫(3*)開啟了一場對話。這樣的對話背後,或許預示著一種消散——就像是一個水壺(4*)在黑暗中沸騰後逐漸褪去,只剩下繚繞的蒸氣在暗影中盤旋。因此,這是對一種既不完全平靜也不單一絕望的繪畫狀態的展現,它超越了這些對立面:一種無需言語就能表達的繪畫。這樣的呈現不再基於具象與抽象之間無法解決的緊張關係,而是一種超越這種對立的第三類型,粉色、黑色與綠色,或者說是靈性與世俗,在一個區域內自由遊走,這個區域不過是通往無法衡量境界的踏腳石。

即使凝視是如此幽暗,無論黑暗有多濃重,那些微妙差異中的亮光也總會透過漆黑顯現無遺。那些明亮與抵抗的形象彼此相遇並結合,它們一起創造出一幅展示發展或轉變過程的圖像。在這樣的框架下,同類型的作品有戈雅的《狗》(1819-1823),畢加索的《面對死亡的自畫像》(1972),以及古斯頓的《水壺》(1978)。這三幅作品都呈現了在虛空中獨自存在的人或物,它們在人類情感經驗的邊緣上演著在極端狀態下事物和人物的變化、分解或崩塌。這些畫為何會在同一空間交匯?它們的呈現已經帶上了一層難以捉摸的神秘色彩,好像是真實與虛幻之間的交界,生命與死亡在這裡相遇。晚期的作品是否總帶著這樣的標誌——一種幾乎瘋狂的感覺?所以,這不只是混合了三幅畫的風格,更是一種敘事的探索,將幽靈般的元素、虛構的情節和現實的細節融合在一起。那麼,如果其他畫作開始被看作是這些作品生命之後的內在投射,缺失了作者的痕跡,那會怎樣呢?顯然,這只是一種構想上的投射,它標示著跨越既定界線的嘗試,或者說是將呈現的現實放大到一種無法實現的程度。這種跨越界線的行為,難道不是對那些規範秩序、界定主客體界限、並將個體框定於既有體系中的學科法則提出了質疑?所有這些或許會讓我們回想起道元禪師/詩人的洞察——人們可以通過眼睛聽到聲音。想像一個基於這樣邏輯的繪畫空間。這無疑是我們探索無限可能的踏腳石。

1*. Dogen Zenji (1200-1253) was a Japanese Buddhist priest who was also a poet and philosopher. He travelled and studied in various monasteries in China. One of his sayings was: “To study the Self is to forget the Self.” 道元禪師(1200-1253)是一位日本佛教僧侶,同時也是詩人和哲學家。他曾在中國的多個寺院旅行和學習。他的一句名言是:“學習自己,就是忘記自己。”

2*. For a discussion about vestiges see Jean-Luc Nancy, The Muses (Chapter 5) Stanford University Press, 1996 關於痕跡的討論,可參見讓-盧克·南希的《繆斯》(第五章),斯坦福大學出版社,1996年。

3*. In referring to Goya’s late paintings I was thinking of ‘The Dog’ painted between 1819 and 1823. The painting was executed directly on the wall and as such was not executed with a public in mind. There is a sense in this of painting enduring at a limit. It is this limit experience that attracted Guston to such a work. Goya was painting at the inaugural beginning of the impulse towards modernity but appeared to understand its closure at the same time. The meeting point of late Goya and late Guston is in an idea of a “radically darkened art” that Adorno evokes in his last book ‘Aesthetic Theory’ (1970).在提到戈雅的晚期畫作時,我想到的是1819年至1823年間繪製的《狗》。這幅畫是直接在牆上作畫的,因此並非為公眾所繪。在這其中有一種繪畫在極限中持續的感覺。正是這種極限體驗吸引了古斯頓對這樣的作品的興趣。戈雅在衝向現代性的初步開端時期繪畫,但似乎同時理解了其結束。晚期的戈雅與晚期的古斯頓在一個想法上相遇,那就是阿多諾在他的最後一本書《美學理論》(1970)中所喚起的“徹底變暗的藝術”理念。

4*. The Kettle, 1978 《水壺》1978年。

Phillip Guston @ Tate Modern

Until 25 February 2024

Text by 撰文 x Jonathan Miles

Translated and Edited by 翻譯及編輯 x Michelle Yu 余小悅