Essential Experiments: Zhang Peili

On the Possibility of Alternative Readings

必要的實驗:張培力——探討另一種閱讀的可能性

TEXT BY 撰文 x XUHUA ZHAN 湛旭華

EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY 編譯 x CHRIS BERRY 裴開瑞 XUHUA ZHAN 湛旭華

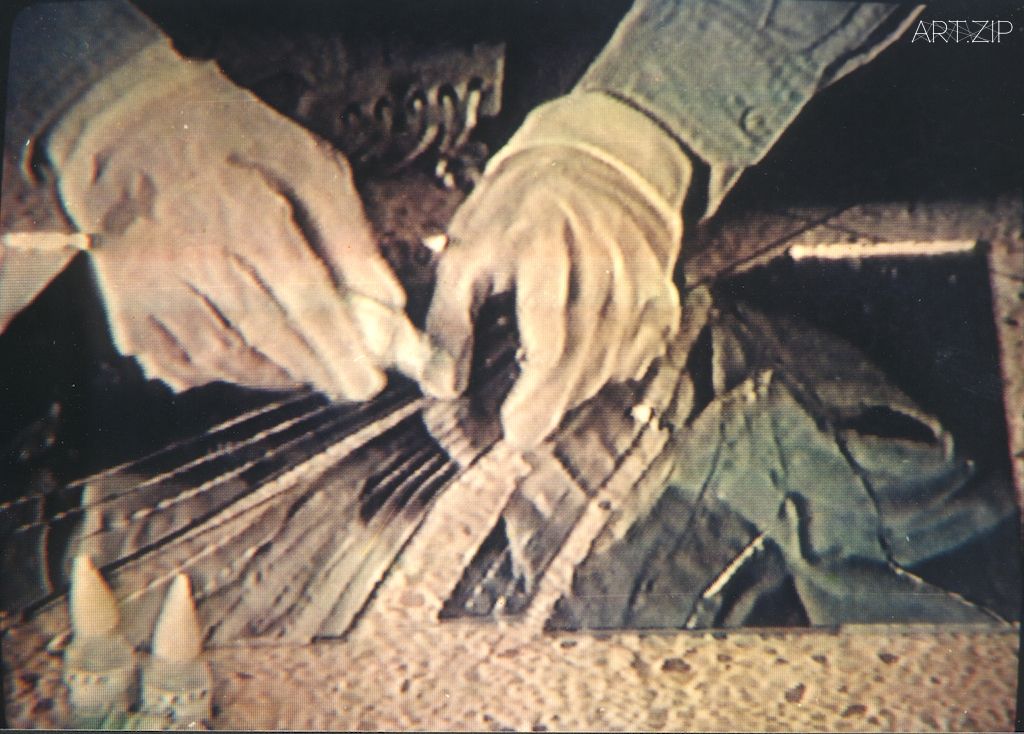

The artist Zhang Peili brought his work ‘30 x 30’ to the 1988 Conference of Contemporary Art in Huangshan. He intended for the audience to be locked up in a room watching his new work for three hours nonstop. Shot with a home video camera, it is a 180-minute video that shows a pair of gloved hands repeating the process of breaking a mirror, then gluing it back together, and then breaking it again. However, people lost patience in less than 10 minutes, and the premiere of China’s first video art work was abruptly interrupted. Shot from a fixed position without any post-production editing or post-dubbing, this piece not only launched video art in China, but also became a topic of hot debate for years to come.

Zhang Peili cannot be neatly labelled as a “video artist” or “new media artist,” and he does not like to be geopolitical labels like “Chinese” either. Looking beyond the Chinese origins of his source materials, Zhang Peili’s art takes the objects themselves as givens. His work interrogates media conventions and the relationship between individual agency and dominant ideology, including a variety of ‘ism’s. Zhang keeps emphasizing that his art “never specifies any ‘principles’ but only some ‘concrete facts.’” He is even uncomfortable with a term like “experimental”: “An experimentation with principles is not experimental at all; abandoning experimentation may be more experimental.” His work communicates his philosophy and logic: casting doubt on dogmatism, mainstream perceptions and assumptions, and instead verifying through his practice.

To Zhang Peili, photography, film clips and video are the “source elements for his creation.” This May, the British Film Institute (BFI) is holding a screening entitled “Essential Experiments: Zhang Peili” to present an overview of Zhang’s video art practice. The show is divided into three parts. First, there are the 80s’ and 90s’ work that embodies the concept of boredom and the aesthetics of manipulation through video’s medium specificity: “30 x 30”, “Document on Hygiene No. 3”, and “Water—The Standard Version from Cihai Dictionary.” Second there are works made from 2000 onwards which generate “multiple possibilities for reading through “revisionary montage” and “re-creation with found footage from old films”: “Actors’ Lines”, “Last Words”, and “Happiness”. Finally, outside the screening room, there is the cake installation work “07 May —27 May” that analyses the relationship between the virtual and realist properties of images through an experiment with ‘Liveness.’ .

I have a conversation with Zhang Peili prior to the BFI exhibition.

ART.ZIP:You started out painting in oils, and then turned to video art. Why?

APL:The art media keep changing. As you know Chinese only use ink and watercolour. Oil painting, print and photograph are all from the West. When we were studying oil painting in the 1980s, we didn’t know about video art, but then we discovered that art had greater possibilities than we could realize. It was very exciting. But it also had something to do with personality. I like to look beyond the place where I now stand, and I’m always eager to try new possibilities.

ART.ZIP:Although China was not very open in the 70s and 80s, some examples of new media art got through. Who was most influential?

APL:We knew people were working with video, but we couldn’t get to see the works. We knew about Nam June Paik and Bruce Nauman, but we only had journals and low quality photos to go by. When it comes to influence, perhaps other things such as philosophy, literature, films, dramas and art theories were more important. For example, we could watch some great films, like Wenders’ Paris, Texas. All those long takes were something we had not seen before. I was among the very few who had the patience to finish the screening. Other film such as The Godfather, and Once Upon a Time in America were popular amongst artists. I was amazed by Ingmar Bergman, and The Tin Drum is my another one of my favourites, which I have watched several times. We also exchanged videos amongst ourselves of films like 8½, Blow-Up, and Last Tango in Paris.

ART.ZIP:You used home video cameras to make videos, then footage from old films, and now you do video installations. When you are using different new media what are most concerned about?

APL:All I care about is new possibilities- the possibilities for creating a new language. I hate repeating myself or others’ ideas. Abandoning the old for the new is an important attitude in art. All the revolutions in the history of art stem from the desire for the new and dissatisfaction with the current situation.

ART.ZIP:You insisted that we should not subtitle your works. Why?

APL:As far as I am concerned, I hope the audience will pay attention to the fundamental aims and attitude of my works, and not to the dialogue in the film clips. Adding subtitles would be superfluous. Furthermore, no attention at all was paid to the dialogue in the process of creating the works. In a film what the characters say is important for articulating the narrative, but the dialogue is not important to my work. Whether there is dialogue or not is irrelevant to the distinction between video art and film. For some artists’ works, dialogue is important, but not for mine. So, I am not trying to make a distinction between art and film by insisting on no subtitles. It is just that they would be superfluous to the works.

ART.ZIP:Can you tell us about your future plans for new work?

APL:I never make plans. I take it as it comes. But the new work has something to do with procedure. It will be another version of the cake installation, in that it will also be videoed for a long time and a procedure of real-time playback. I am still working it out, but to sum it up, it will use procedures to challenge people’s observations of neutral objects, as well as their thinking about the uses of visual media and re-ordering of procedures for observation.

ART.ZIP:This is your first time at the Chinese Visual Festival. Do you have any suggestions for the curators?

APL:The Chinese Visual Festival provides an excellent opportunity for artists to be known to the Western art world. Artists need this opportunity for mutual dialogue with the outside world: communication helps understanding. European and American understanding of Chinese contemporary art is uneven, and there are mutual prejudices and knowledge – understanding requires time. China’s politics is different from that of the West, but its economy has been very strong recently, and that has drawn many Westerners to want to understand China more. Of course, should these circumstances be reversed, then the interest will disappear. From this we can see that too much emphasis on national background and group consciousness has nothing to do with artists, and I am quite resistant to the idea of being included in group shows with other Chinese artists. Western critics do not concern themselves with whether an artist is British or American when they are studying other artists.

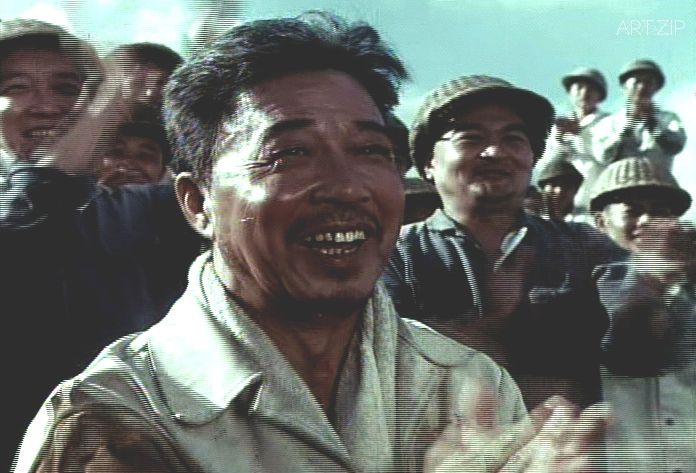

- 《喜悅》

- 《喜悅》

Prof. Chris Berry of King’s College London on Zhang Peili’s visit:

I’m excited about Zhang Peili’s screening at the UK’s flagship venue – the BFI Southbank – but not only because it introduces single channel Chinese video art to British audiences. The BFI Southbank is a cinema, and the “F” in “BFI” stands for “Film.” But Zhang Peili insists that his work should not be confused with film. Of course, the distinction between film and video art was very clear when he began working. But in the digital age, isn’t it more blurred? I’m looking forward to hearing Zhang’s opinions on the distinction between video art and film today. And I also want to know why he is willing to show his works in a cinema environment.

Essential Experiments

“Essential Experiments” is a monthly programme of artists’ moving image work at BFI Southbank in London. Essential Experiments takes place every month and screens a wide variety of work form the full range of artist’s moving image practice from avant garde classics to contemporary digital works in order to provide the audiences with the context in which the works were made and way of understanding them. Past programmes have included work by: John Akomfrah; Nathaniel Dorsky; Grayson Perry; Yvonne Rainer; Carolee Schneemann; Gillian Wearing; and many more.

“Essential Experiments” is curated by William Fowler, Curator of Artists’ Moving Image at the BFI National Archive and Helen de Witt, Head of BFI Cinemas.

In addition to “Essential Experiments: Zhang Peili”, the BFI will also host “Essential Experiments: Introducing Chinese Video Art,” featuring video art work by Chinese artist Yang Zhenzhong, Kan Xuan, Wang Gongxin, Jiang Zhi, Yang Fudong, Lu Yang, Zhang Ding, Peng Yun and Wu Xiaohai in May 2015. The programme is co-curated by Xuhua Zhan, curator of Chinese Visual Festival and Chris Berry, professor of King’s College London.

Reference

- Dal Lago, F.Gladston,P and Huang,Z.et al.(2011)Zhang Peili: Certain Pleasures. Minsheng Art Museum

- CCAA. (2010) CCAA Lifetime Contribution Artist: Zhang Peili.CCAA

- Dong,B.et al. (ed)(2010)Looking Through Film: Traces of Cinema and Self-Constructs in Contemporary Art.New Star

- Minsheng Art Museum.(2011) Chinese Moving Image Art 1988-2011. Minsheng Art Museum

- Meigh-Andrws,C.(2014)A History of Video . Bloomsbury

- Rush,M.(2007)Video Art.Thames & Hudsono

1988年,黃山現代藝術討論會上,藝術家張培力帶來了一件作品《30X30》,按藝術家的設想:觀眾將被關在反鎖的房間裡三小時不停歇地觀看他的新作——以家用攝影機拍攝的180分鐘錄像裡重復播放一雙帶手套的手不斷地摔碎一塊鏡子,然後粘合,再摔碎的過程。但放映不足10分鐘後,影片就被焦躁的觀眾打斷了。這件以固定機位拍攝,無後期配音和剪接的作品成為最早的一件中國當代移動影像作品和中國當代藝術史上一個被不斷討論長久的話題。

張培力無法被簡單地歸類為一個“錄像”或“新媒體”藝術家。也許,因為其獨有的警覺的思維方式正體現在不斷挑戰各種先驗觀念的工作方式上,他甚至不願被定格於中國人的身份或被地緣政治化概念解讀。如果抽離他作品中“國產”的那些元素——它們只是在他的世界能順手拈來的創作“物質”而已。正如沒有誰會為一塊油畫布打上東西方標簽之分。

張培力一直強調他的工作‘從來不制定任何原則,只是一些具體事實”甚至“實驗”這類詞都讓他感到不自在:“有原則的實驗並不是實驗,放棄的實驗也許是實驗”(見黃專文)。剝離中國化特定語境的解讀,可以看到藝術家自己對事物的態度是客觀自然的,他的作品體現了他的哲學思想與邏輯:對教條主義、主流認知等各種先驗觀念提出的簡潔理性卻鋒利的詰問並以藝術反復驗證,同時展開另一種閱讀的可能性。

拍攝、電影素材和影像對張培力而言是一種“創作元素”,2015年5月英國電影協會(BFI)將以《必要的實驗:張培力》集中回顧張培力的移動影像創作。這次展覽分三部分:80-90年代以錄像制作體現無聊和控制美學的:《30X30》、《(衛)字3號》 ,《水-辭海標準版》;2000後以“影像蒙太奇修正”手法,用50-70年代老電影素材創造“不同的閱讀可能性”:《臺詞》、《遺言》、和《喜悅》;還有用“場景性”實驗剖析影像的虛擬和真實之間邏輯關系的影像裝置作品《5月7日-5月27日》。

借著這次BFI的展覽,我們邀請了藝術家談談他的創作。

ART.ZIP:您早期學習油畫,後來轉到錄像藝術。是什麽驅動了這個創作上的改變?

ZPL:藝術家使用的媒介手段一直在改變中:最早中國只用水墨,後來西方傳來油畫和版畫,後來有攝影,這都有別於中國的傳統藝術媒介。80年代之前學油畫時,我們還不知道錄像藝術,原來藝術的可能性比我們了解的多得多。等有了技術和物質條件,為創作提供了刺激,驅動了新的嘗試。用什麽手法創作跟個人態度有關:有些藝術家對媒介態度較穩定,我可能不太安分——對於自己已經習慣、太熟悉的事缺乏興奮,當有新的可能性總想去嘗試。簡單說是外部條件和內在條件決定。

ART.ZIP:在七八十年代,當時的信息不是很開放,但也有一些資料能通過各種渠道了解。當時有哪些電影作品和藝術家對中國第一代新媒體藝術家影響比較大的?

ZPL:實際是我們當時受到的影響是多方面的,不僅是錄像藝術(Video Art)。80年代早期我們已知道國外藝術家用錄像創作,但當時我們只看到一些文獻和模糊圖片,如白南準和布鲁斯·諾曼(Bruce Nauman),但沒看過作品。當時的影響更多來自哲學,文學,電影,戲劇,藝術理論。 這跟早期西方油畫傳到中國不一樣,西方人企圖讓油畫能融入到中國的欣賞習慣中。影院當時能看到一些不錯的電影,如娜塔莎·金斯基(Nastassja Kinski)主演的《德克薩斯州的巴黎(Paris,Texas)》。當時我驚訝於這部電影沒有很炫的情景、動作和拍攝手段,卻有很多長鏡頭,前所未見。但觀眾覺得片子很悶,最後影院只剩下我。除了電視臺和影院公映的,更多在錄像廳看到如《美國往事(Once Upon a Time in America)》和《教父(The Godfather)》等影片。看到英格瑪·伯格曼(Ingmar Bergman)的電影比較晚,但那是讓我最激動的; 還有《鐵皮鼓(The Tin Drum)》、我看了很激動,看了好幾遍。 再後來大家常交互錄像帶看如《8½》、《巴黎最後的探戈(Last Tango in Paris)》和《放大(Blow-Up)》等。

ART.ZIP:您使用錄像制作,使用電影片段,到後來用錄像裝置。在使用這些不同的新媒體創作元素中您最關注什麽?

ZPL:我最關注的是新的可能性——新的語言的可能,在創作中語言的重復——重復自己或別人都是很可怕。藝術中的喜新厭舊是很重要的態度。所有的藝術史上鬧出來的一些事/藝術上的革命最基本的都是喜新厭舊,不滿足。

- 《喜悅》

- 《喜悅》

ART.ZIP:您的作品如《喜悅》、《遺言》在國外放映不加字幕,講講您的想法?

ZPL:對於我來說,我希望觀眾關注的是我做作品的基本動機和態度,而不是使用的電影片段裡的臺詞,字幕加在裡面是畫蛇添足。而且這個作品創作時本來就沒有考慮對白的。對電影來說角色說什麽對電影陳述什麽故事是重要的,但對於我來說,對白臺詞不重要。有沒有臺詞不是區分錄像藝術和電影的絕對的標準,不是用於區別電影和錄像藝術,對某些藝術家的作品來說:對白臺詞是重要的;但對我的這些作品來說,對白臺詞不重要,我並不是用不加字幕來區別這是藝術而不是電影。針對作品而言,加字幕是多余的。

ART.ZIP:能談談您的新作或是未來的創作計劃嗎?

ZPL:我從來沒計劃。最近考慮的作品跟程序有關系。好像《蛋糕》這個作品,我準備做另外一個版本,也是長時間的記錄拍攝,中間增加了一個可實時回放的程序。這還在構思階段。簡單一點說從程序上挑戰人對客觀事物的觀察,對視覺媒介,重組程序在觀察中的作用和角色的思考。

ART.ZIP:這是您第一次參加華語視像藝術節,您對這個以推動中國獨立影像作品和當代藝術為目的建立的藝術節什麽建議?

ZPL:我覺得華語視像藝術節給藝術家提供的機會很好,藝術家很需要機會跟外界對等的交流,相互多了解對彼此都有幫助。歐美各個層面對中國當代的了解不一樣,西方對中國當代藝術的了解或偏見是相互的,了解需要時間。中國政治形態跟西方很不一樣,但經濟近年又很強,這吸引很多西方國家想要更多了解中國,但如果這個情況倒過來,那吸引眼球的情況就不存在了。從這個上面講,比較忌諱過度解讀國家背景,群體意識,這個跟藝術家沒關系。作品裡面帶國家民族意識是另一碼事,不需要期待西方認同,藝術家把自己的事情做好。很排斥動不動一個中國藝術家群展,西方在研究藝術家他們不會以國家標簽區分這個是英國、那個是美國。

談到張培力的展覽,倫敦大學國王學院裴開瑞教授說:我們為張培力教授這次在英國的旗艦級電影藝術機構——英國電影協會南岸中心的展覽感到非常興奮。不僅因為把中國影像藝術介紹給英國觀眾;BFI的‘F’指的是電影,但張培力的作品不是傳統意義上的電影,作為藝術的影像與作為電影的影像分界在張培力的創作之初就非常清晰。但在數碼時代,這個分界是否開始變得模糊?我們期待傾聽張培力對今天影像藝術與電影的身份標識的觀點。我也想了解他對在非美術館空間的電影院放映他的作品的想法。

必要的實驗

“必要的實驗”是由英國電影協會南岸中心舉辦,關注於藝術移動影像電影和先鋒藝術電影研究的長期項目。“必要的實驗”每月舉辦學術放映從經典先鋒藝術到當代數碼作品等不同類型跨界藝術影像作品,通過放映、策展人、學者、藝術家的交流講座促進觀眾對作品語境、創作思路的了解,探討影像、電影與藝術的內在聯系和各種潛在可能性。過往學術放映項目包括:約翰·亞康法(John Akomfrah);纳撒尼尔·多斯基(Nathaniel Dorsky); 格裡森·佩里(Grayson Perry); 伊馮‧芮娜(Yvonne Rainer);卡若琳·史尼曼(Carolee Schneemann);吉莉安·韋英(Gillian Wearing)等藝術家的作品。項目策展人是英國電影協會資料庫藝術家移動影像策展人威廉·福勒(William Fowler)和BFI影院負責人海倫·德威特(Helen de Witt)。

2015年5月,“必要的實驗”攜手華語視像藝術節策展人湛旭華和倫敦大學國王學院裴開瑞教授,首次把眼光投向中國當代移動影像藝術,合作策劃兩場專場映展:“必要的實驗:張培力”和“必要的實驗-淺談中國錄像藝術”介紹包括楊福東、闞萱、王功新、楊振中、陸揚、蔣誌、彭韞、張鼎和吳嘯海的影像藝術作品。

參考文獻:

- 《張培力藝術工作手冊》,2008,編著:黃專/王景,嶺南美術出版社

- 《張培力:確切的快感》,2011,編著:Paul Gladston, 黃專,Francesca Dal Lago, Robin Peckham, 姚嘉善,民生現代美術館

- 《2010中國當代藝術獎 終身成就獎:張培力》,2010,CCAA

- 《從電影看:當代藝術的電影痕跡與自我建構》,2010,編著:董冰峰/杜慶春/黃建宏/朱朱,新星出版社

- 《中國影像藝術 1988-2011》,2011,民生現代美術館

- 《A History of Video Art》,2014,編著:Chris Meigh-Andrews, Bloomsbury

- 《Video Art》,2007, 編著:Michael Rush,Thames & Hudson