TEXT BY 撰文 x HAO ZHIZI 郝智梓

IMAGES COURTESY OF 圖片 x Aperture 光圈出版社

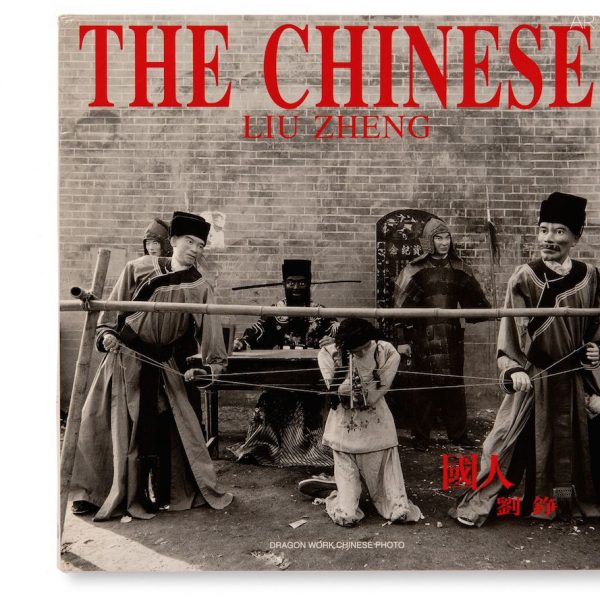

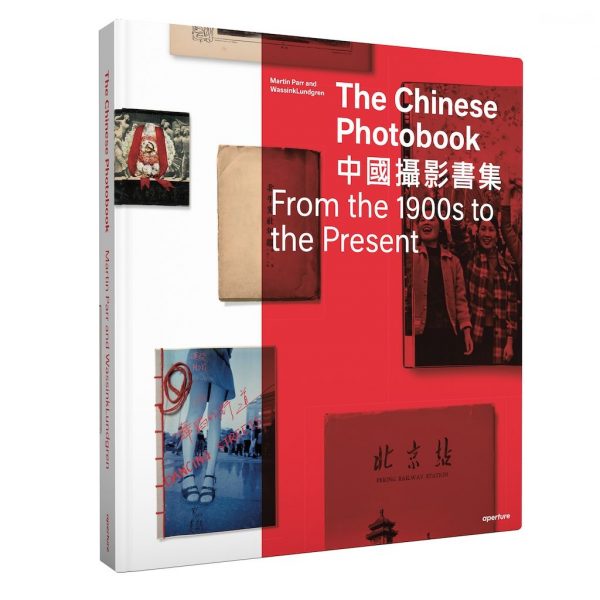

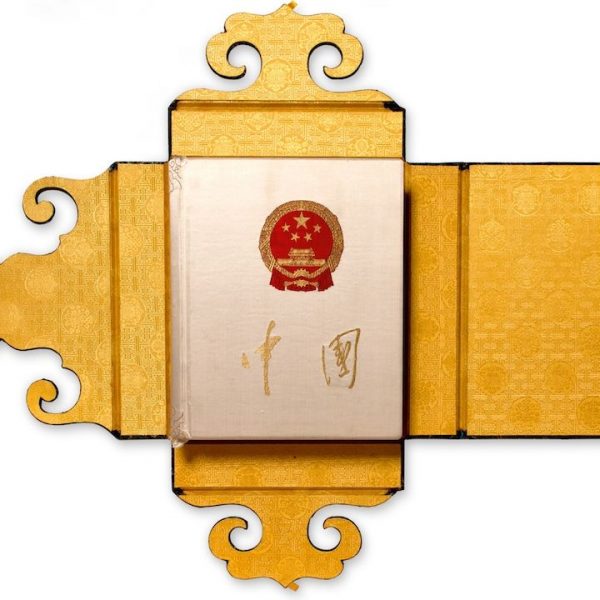

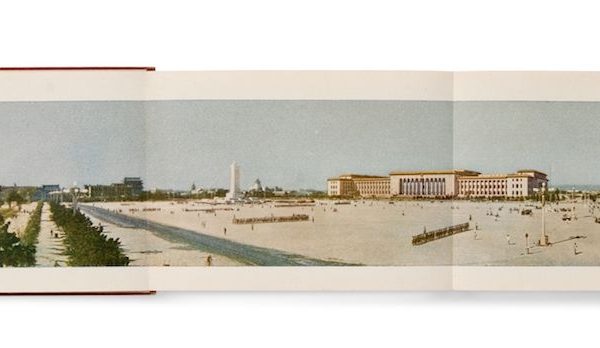

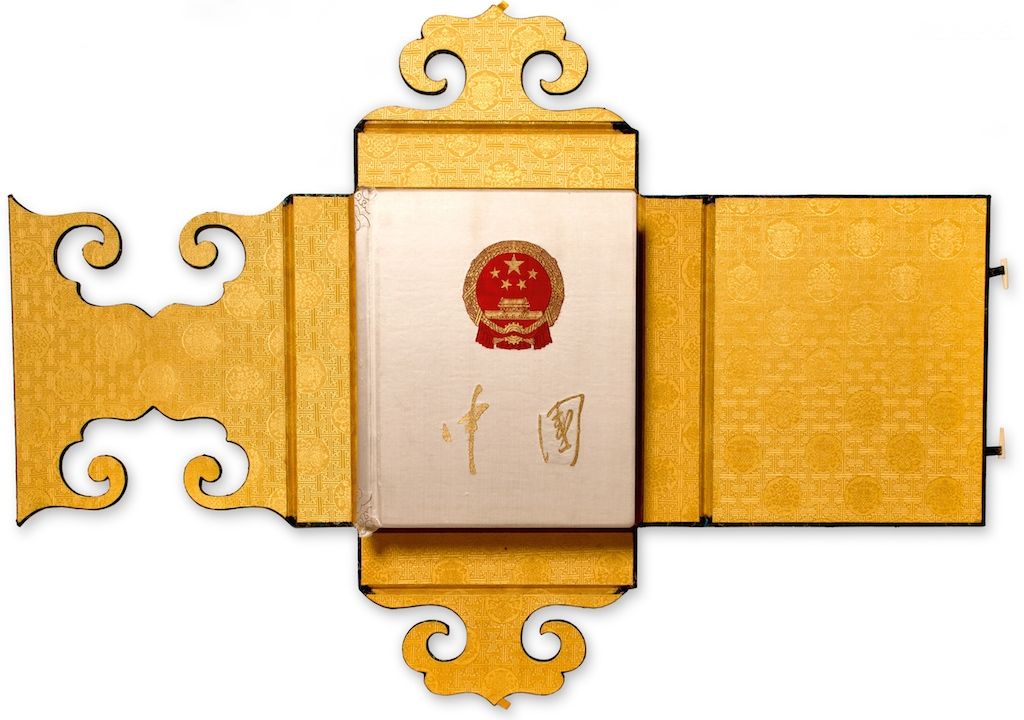

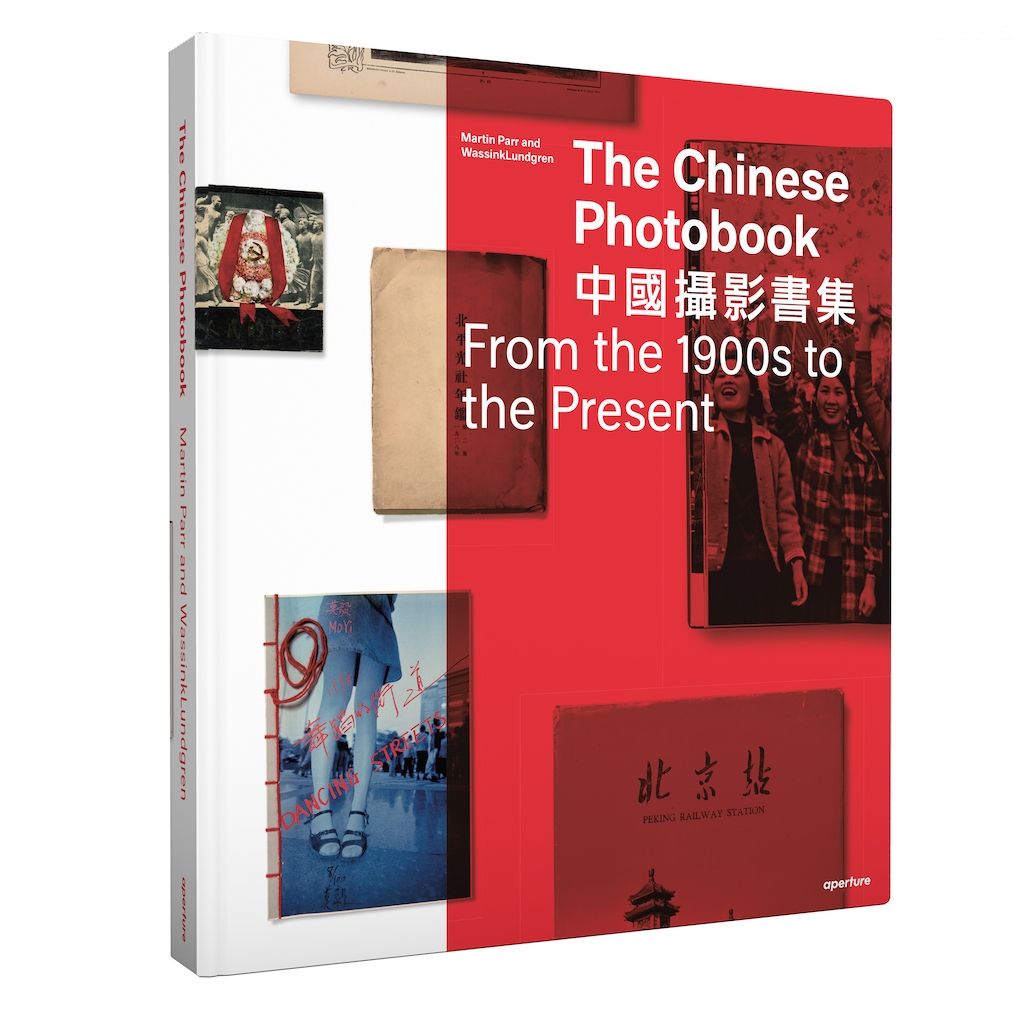

In the 20th century, “photobook” was produced as an effective media for recording history and reflecting the development of the history of photography. However only in the last decade there has been a major reappraisal of the role and status of the photobook within the history of photography. China boasts a fascinating history of photobook publishing, the oversea photographers and artists who have concerned about China have been studying on it for years, trying to light its historic position worldwide. Based on a collection compiled by British photographer Martin Parr and the Beijing-London-based Dutch photographer team WassinkLundgren, the Chinese Photobook illustrates the history of Chinese photobook making over a century vivid to the world for the first time, together with its country’s diversity, richness, and vigorousness. With the support of the Cultural and Education Section of the British Embassy, the Aperture Foundation and many other institutions, it has been presented in Arles, New York, Beijing and London successively. Besides, a book of the same titled has also been published in 2015 by Aperture and the China Photographic Publishing House. Curiously, none of the three curators is from China. We interviewed Martin Parr and Thijs groot Wassink, and talked about their experiences in the photos of China.

攝影書是記錄歷史、反映攝影史發展的有效載體。雖然誕生了一個多世紀,但只有在近十幾年它才開始受到廣泛的關注。中國的攝影書出版史頗為繁盛,多年來海外攝影界以及關注中國發展的藝術家一直對其進行歷史研究工作,試圖還原它在世界範圍內的歷史地位。 《中國攝影書集》是由英國攝影家馬丁·帕爾(Martin Parr)同荷蘭藝術組合魯小本&泰絲(WassinkLundgren)共同合作的項目成果,講述了中國攝影書從1900年來的百年歷史,並首次向世人展示它在這百年間體現出的多樣性、豐富性和強大的生命力。在英國大使館文化教育處、紐約光圈出版社等多家機構的大力支持下,展覽先後在法國阿爾勒、美國紐約、中國北京及英國倫敦亮相。同名書籍《中國攝影書集》也於2015年正式發行。值得注意的是,該展覽的三位策展人中竟然沒有一位中國人。為了更好地了解展覽背後的故事,我們采訪了其中兩位策展人,馬丁·帕爾和泰斯·格羅特·瓦辛克(Thijs groot Wassink)。

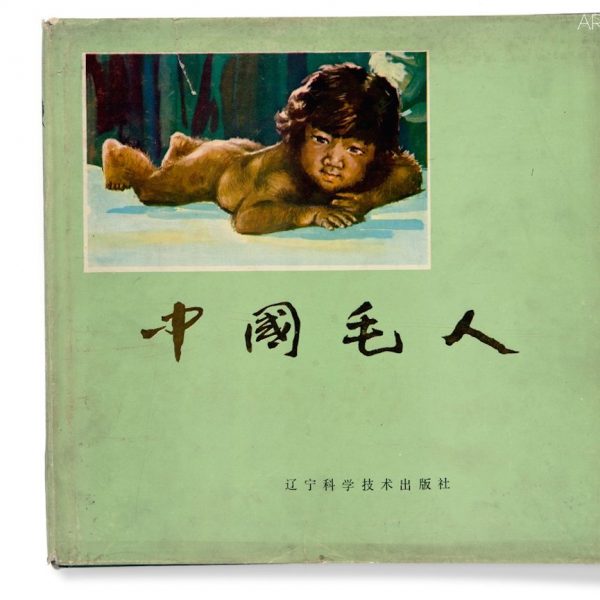

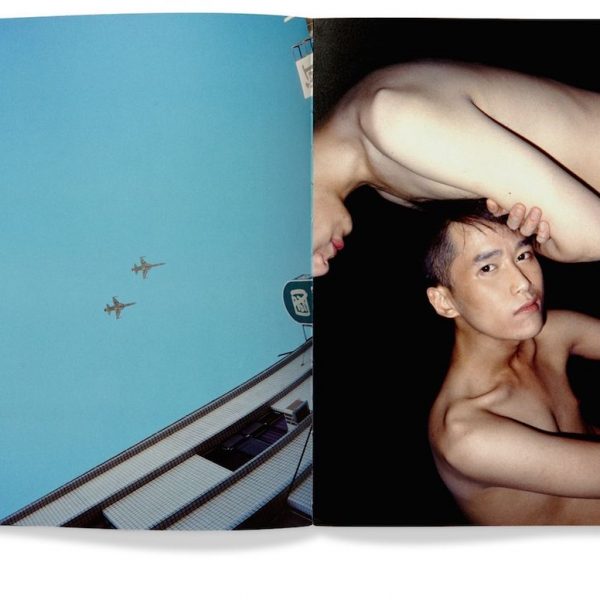

“Beijing Silvermine” is a project started by the French photographer Thomas Sauvin who has lived in Beijing for over 10 years. It is an archive of half a million abandoned negatives salvaged over the years from a recycling plant on the edge of Beijing, covering a period of 20 years, from 1985, the year that witnesses the booming of silver film photo, to 2005, when digital camera finally dominates. Surprisingly, those negatives lying in the rubbish dump, turn out to be perfect approaches to understand the modernisation of Chinese people’s life and the great social change in China. The photobook made by Sauvin, is an exhibit of “The Chinese Photobook” exhibition and was displayed earlier in The Photographers’ Gallery, London. The Beijing Silvermine project is like an epitome of the whole exhibition, which also tries to explore the mine of Chinese photobook.

ART.ZIP: How did you first notice such a huge yet unexplored area of Chinese photobook?

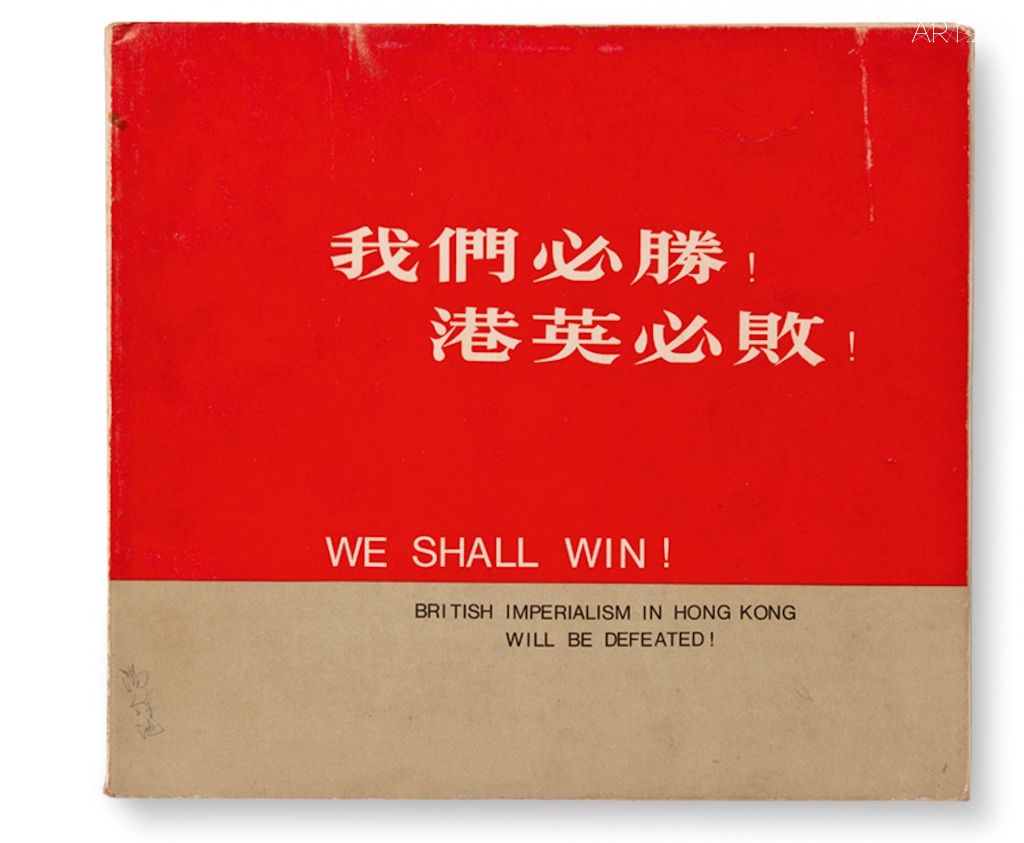

TW: It started with Ruben (Lundgren) and myself first going to China in 2006, where we did our first project there together, the Empty Bottles, after we graduated from BA in Netherland. The book we made won a prize at a festival in France. Martin Parr saw that book, and he liked it, so he contacted us. He has a big interest in photobooks in general, and has made a book called “The Photobook: A History”, which contains three volumes focusing on the world history of photobooks. In those books, there were maybe three Chinese photobooks, and he felt that probably there should be more. Then Martin went to China for his own work, and found Ruben there, who has been living in Beijing for years. Since Ruben could speak mandarin, Martin asked for his help to find some photobooks. Ruben found some books at the Panjiayuan flea market in Beijing, and they were about Cultural Revolution. Martin really liked them.

MP: We then decided to do a project together about Chinese photobook which took about 7 or 8 years to achieve. So Ruben would buy the books in China, and I would buy them in Europe. Together, we sort of made a collection, and the project was published as a book: The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present.

.

TW: When we were building up the collection, we found out that almost nobody else knows about Chinese photobooks. So it was like an open door, and we thought that maybe we should show this to the world, and so the idea of an exhibition emerged.

MP: The show ran in Beijing earlier in this year, and it’s probably going to a tour in China as well, although it has been to London and New York as well, and the Arles Festival in France. So it has some quite wide exposure.

======

There is always a chance that a culture being watched from outside would be transformed by this gaze into merely a spectacle. This happens even more often when the object is “Oriental”, as suggested by Edward Said in his book, Orientalism. The curators of The Chinese Photobook tried their best to show the most original, authentic China to the Western world. While they were preparing for the project, they also learned more about this “mysterious” country, and its “bizarre” history.

ART.ZIP: During the whole process of building up a collection and later the exhibition, have you learned more about China?

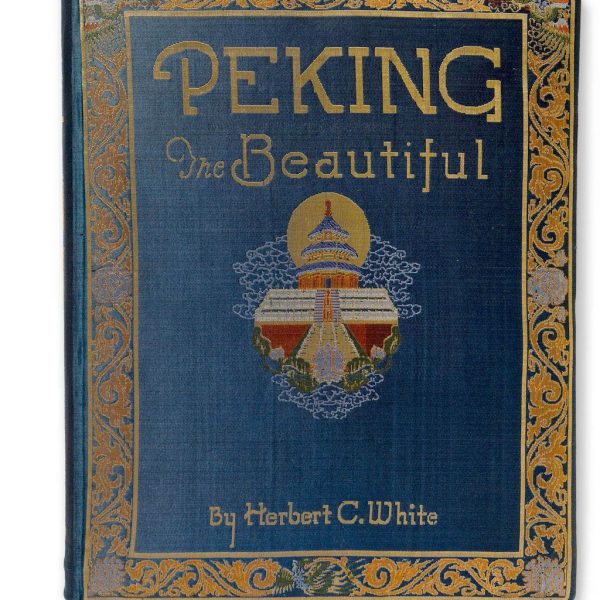

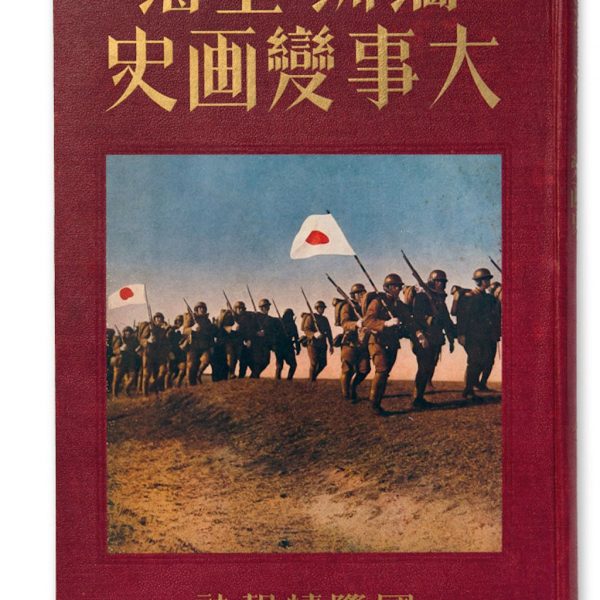

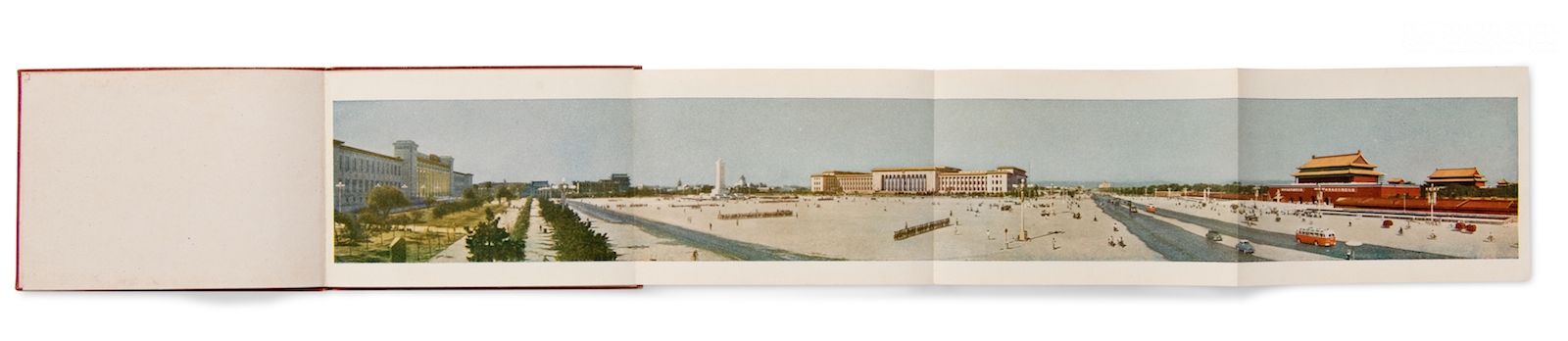

MP: Obviously you learn about China, because you study the books, you study the history of the country that lasts hundreds of years. You see the imperial rule from the colonists, the start of the revolution, and now you see this new emerging fresh generation of artists and photographers who have their own voice, as opposed to the propaganda voice. You also see some history that has not been noticed, during the Japanese invasion for instance, the Manchurians produced very good photobooks and they have a whole chapter in our book, and such history is not included in the mainstream discourse. Viewing the photobooks is like reading the country.

ART.ZIP: Has this changed your mind about China?

MP: No, it hasn’t changed my mind at all. It just confirmed everything I knew, but of course it has great depth. We will still find books now that we didn’t know about, even when we went to a great length you can never find everything. They’ll be other things hidden.

ART.ZIP: Have you worried that while the Westerns are reading or viewing the book or the exhibition from a perspective of orientalism and regard Chinese photobooks as a spectacle?

MP: I wouldn’t worry about it in the slightest. We have books made from China by Chinese photographers, also books from China made by foreign photographers include Japanese and Europeans, so it is a process of looking at the country and the books emerged about that country, from both inside and outside. Bear in mind that we have been doing the same process with Japan, India, Africa, Latin America, it’s all about understanding the greater world of photography and all the connections combining all together.

ART.ZIP: As a westerner what do you think about the photobook traditions in Europe and in China?

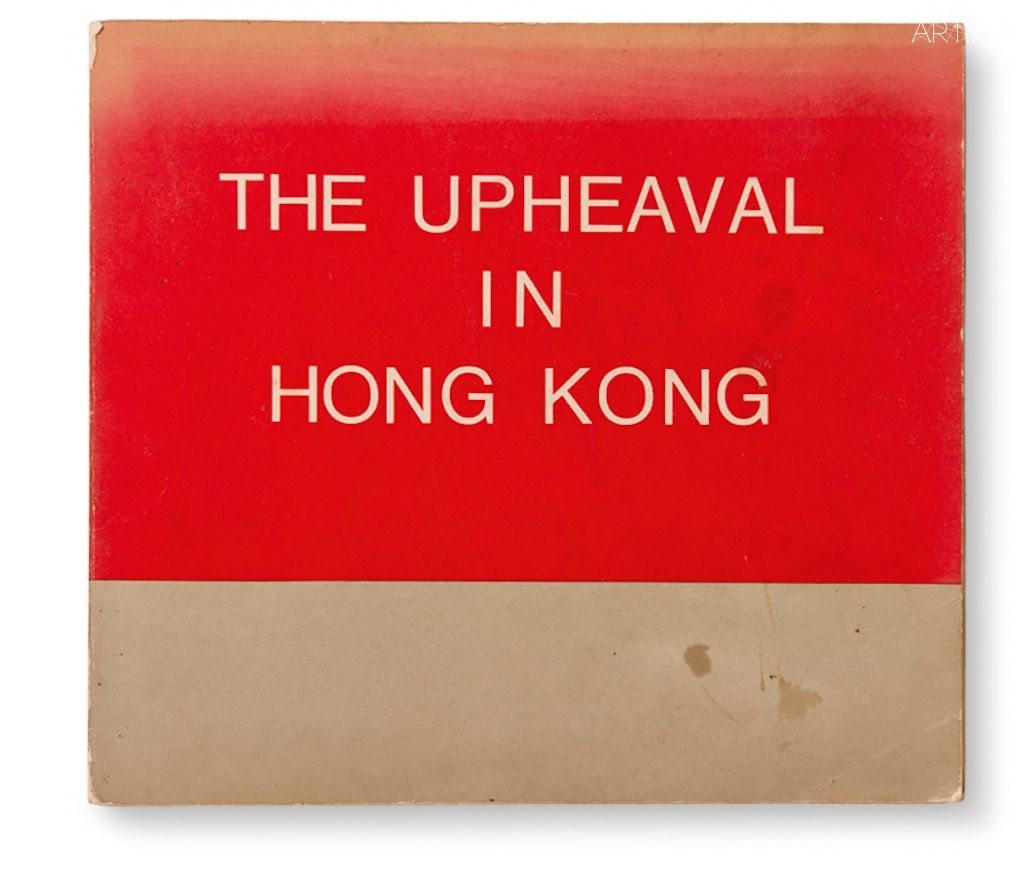

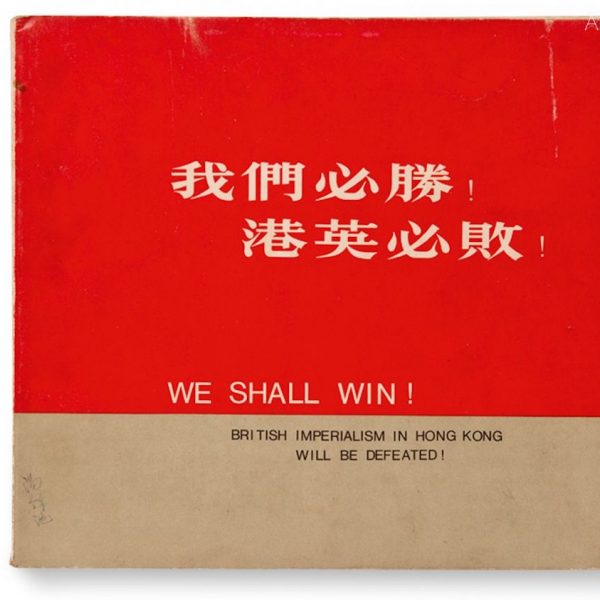

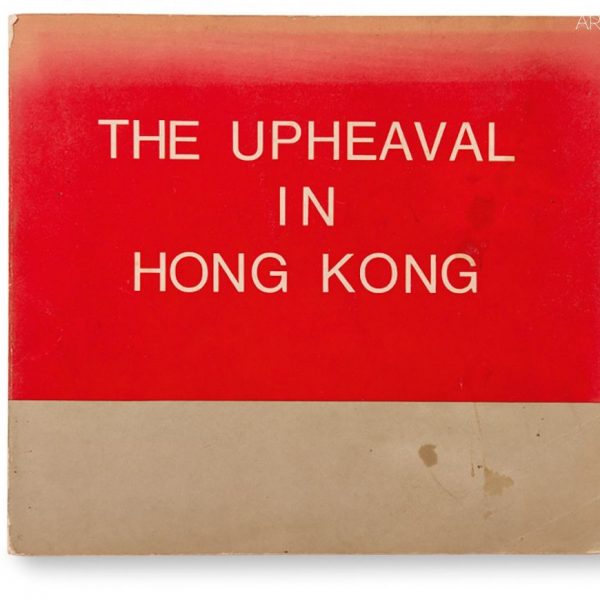

MP: There are some overlaps. You have the new generation photographers who are creating very exciting and interesting new books, which you wouldn’t believe that they could be published several years ago. Obviously in China you have more state propaganda, where the state used to control everything those was published, that has not happened in Europe in recent years. So that’s probably the main difference, you have this added layer of control. So when we showed the books in China, we couldn’t show the Tiananmen Square, and that’s the substantial and important chapter of recent Chinese history, but they have written it out so you can’t even mention it.

=======

The censorship, apparently, has imposed a strong effect on the exhibition as well as the book they made, The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present. All contents relating to the Beijing Turmoil have been deleted from both the exhibition and the book, and they had to introduce a “Mainland version” of the book. Such persistent connections between politics and photobooks actually supports their idea, that photography is never innocent but always is employed by political agendas .

ART.ZIP: I assume there were a lot of compromises in terms of what can be shown and what cannot…

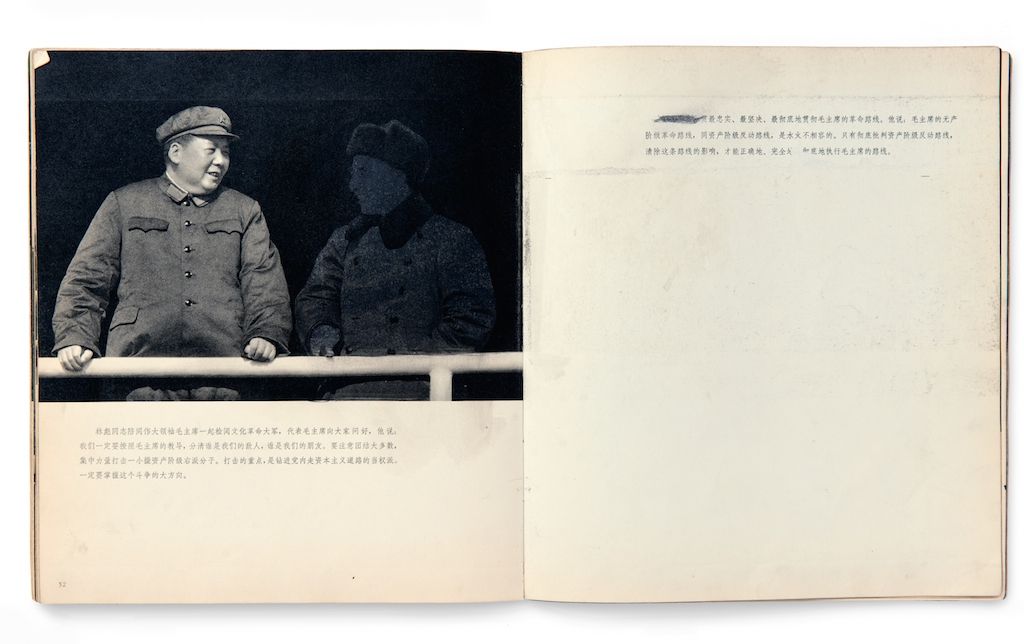

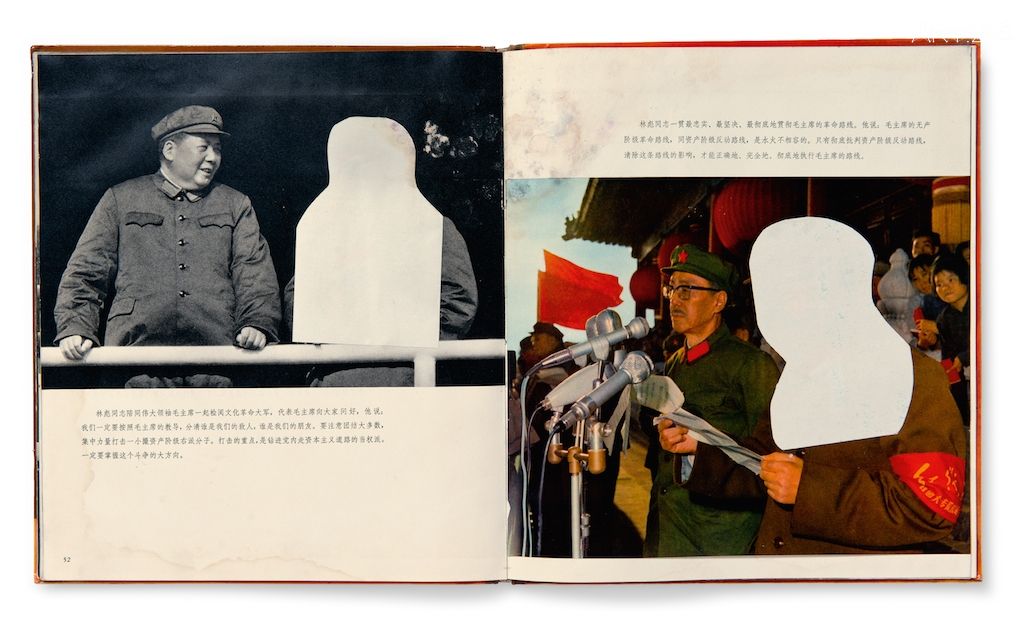

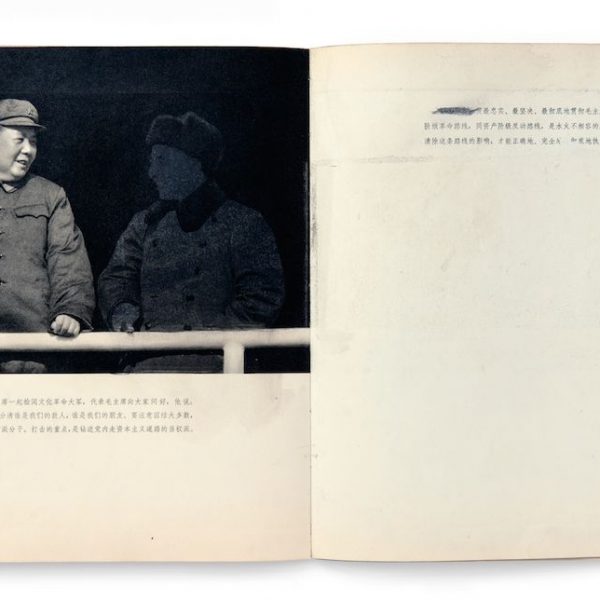

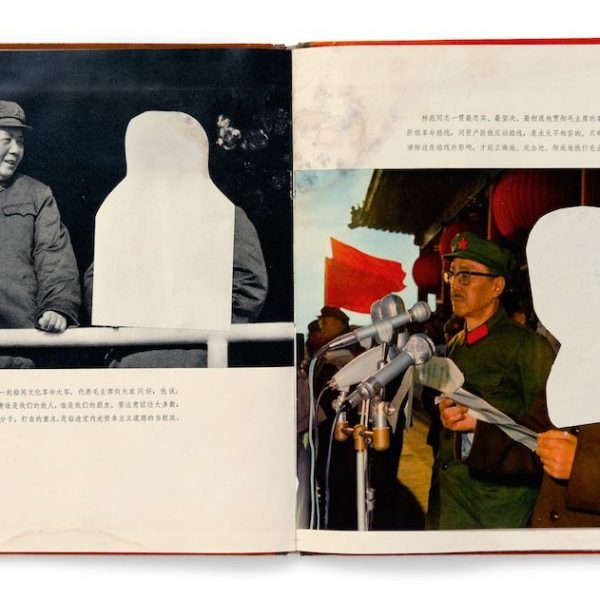

TW: Of course there were compromises. In a way, I think we had to push that as far as we could. If we push it too far, then we would have had nothing (to show), and it’s silly to make something like this and not to show it in China, because it is about China. I don’t want to just step in, take something away and show it only to the west. It’s more interesting to listen to the conversation between people in China and their own work. In a way, the censorship itself is a crucial thing we explore in the book, as well as in the exhibition, just to see how it works. Not only Tiananmen Square, they have done the same thing to Lin Biao as well. Also, during the Japanese invasion, the Japanese photobooks have beautified what they did in China as well. The real history has been modified.

======

For most of us, photobooks are familiar yet unfamiliar. They are familiar, because they are everywhere in our daily life, just as the exhibition reveals; and unfamiliar, because selectively we often ignore them. In most cases, people elide them as they are more propaganda measures than artistic projects, which in turn, stop us opening them from the very beginning. This exhibition encourages one to review and rethink those books. Through reviewing and rethinking, they seem to be more valuable than we once reckoned. What is curious and uncanny here is that the encouragements and urges are from a bunch of outsiders.

MP: The interesting thing is that no one knew about these photobooks. Even in China no one knew about it. People would know certain sections like contemporary work or the propaganda books, but no one was able to put the whole picture together. So I don’t think there is a collection in China that has all these books in. Even in the Chinese national library, they wouldn’t have books from Japan, or the contemporary books from China, they’ll have the state produced propaganda books but not much more.

TW: There were a lot of institutions who are not collecting propaganda photobooks because they think that those photobooks do not belong to the category of art, from their point of view, they’re just propaganda. I imagined if I would have lived through that period, I probably wouldn’t like to look at those books either. However, if you take just a little bit of distance, and just see how photography is used, and abused, to tell certain stories, it becomes something very telling about the medium, and it says something about the history as well. So in that sense, it’s a very important part of this book. Maybe an important reason why this project has not been made in China yet is that because you are too close to your own history. If you take a little bit of distance, and ask an outsider to show it to you, maybe you would suddenly realise that you have never looked at it in this way. Usually, the deeper you go into something, the more interesting it becomes. However, if you have a natural impulse to look at those images and convince yourself not to think about that because of some reason, you are never going to dive into it, and you will never understand how strange, yet beautiful and special it was. The changing attitude towards photobooks in China reminds me of changed attitude towards the ceramics. A while ago a Chinese friend of mine helped a Chinese collector to buy a piece of ceramic work from the auction house. That work, however, was originally bought from China twenty years ago with a rather low price. I guess that is another proof that sometimes you need the eyes of outsiders to see your own beauty.

“北京銀礦(Beijing Silvermine)”是一個由法國人托馬斯·蘇文(Thomas Sauvin)發起的廢棄底片收集項目。世紀之交的中國,膠片還是攝影的主要方式,而那些不討喜的廢舊膠片的最終歸宿一般都是垃圾場。蘇文收集起了這些膠片,並將它們沖洗了出來。這個項目就叫做“北京銀礦”。令人驚訝的是,那些從前被當作“不好看”和“拍攝失誤”被丟棄的照片在重新沖洗之後煥發了新生——由於多數都是私人攝影,它們成為了那個時代國人審美以及家庭生活狀態最好的印證。“北京銀礦”所制作的攝影書作為本次中國攝影書集展的一部分,不久前在倫敦的攝影師畫廊(The Photographers’ Gallery)展出。而“北京銀礦”儼然是這個展覽的一個縮影:中國攝影書集展也將其視線對準了從未曾被世人注意到的,甚至從某種意義上也可以說是被遺棄了的中國攝影書集這一巨大蘊藏。

=======

ART.ZIP: 你們是如何發現中國攝影書這個巨大蘊藏的?

TW: 2006年在荷蘭讀完本科之後,魯本(Ruben Lundgren)和我第一次去了中國,在那裡完成了我們的第一個項目《空瓶子(Empty Bottles)》。馬丁非常喜歡那本書,便聯繫了我們。馬丁自己對攝影書有著很大的興趣,他曾編著過一套書《攝影書的歷史(The Photobook: A History)》,其中收錄了三本中國攝影集,但他認為中國攝影書集應該占有更高的地位。於是他就來到了中國,找到了當時定居中國的魯本。因為魯小本精通中文,馬丁便請他幫著搜集中國攝影集。魯本便開始在北京的潘家園市場淘書,最早的時候找到的都是一些文革時代的攝影書集,馬丁非常喜歡它們。

MP: 於是我們決定一起做一個關於中國攝影書集的項目,而這個項目花了大概八年的時間。在這八年時間裡,我們不停地搜集攝影書集,魯本在北京搜集,而我在歐洲,漸漸地書就多了起來,最終我們成功地把它們編進了這本《中國攝影書集:1900年至今(The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present)》。

TW: 在收集的過程中,我們驚訝地發現除了我們之外幾乎沒有什麽人聽說過這些書,更別提了解它們了。這是一個並沒有什麽人涉足過的領域,也許我們應該把它們拿出來向世人展示。

MP: 在我們的書出版之後,展覽也應運而生了。這個展覽早些時候已經在北京的尤倫斯當代藝術中心舉辦過了,之後應該還會在中國進行一個巡展。而在國際上,我們在倫敦、紐約和巴黎都舉辦過展覽,曝光度還是比較高的。

======

在文化交流的過程中,誤解和刻板印象幾乎是不可避免的,而這一點在東西方文化的碰撞與交流中則更加明顯:這在愛德華·薩義德(Edward Said)的《東方主義(Orientalism)》一書中就早已有過證明。然而《中國攝影書集》的策展人們則盡力呈現給大眾一個更真實的中國。在準備著作的八年時間裡,他們自己也對中國這個東方國度,以及中國的歷史有了更加深入的理解。

ART.ZIP: 在研究過程中你们對中國是不是有了更深入的了解?

MP: 當然。在研究那些攝影書集的過程中,我們相當於也研究了整個中國的現當代史。你會看到西方列強的入侵,會看到那之後興起的各種革命,還會看到新一代攝影師、藝術家的崛起,而他們發出的聲音則是對從前那個將藝術作為政治宣傳工具時代的反抗。同時我們還會發現一些不為人知的歷史,比如抗戰期間,日本控制的偽滿洲國曾經發行過一些制作非常精良的攝影書集。這是未曾被主流歷史話語所記錄過的,而這段歷史在我們的書中則單獨編成了一個章節。

TW: 因為我們都不是歷史學家,所以我們做了大量的歷史研究工作。這樣一來,我們能更好地把握這段歷史,也能更好地決定我們該把哪些書籍囊括到我們的收藏當中。有一本讓我印象特別深刻的書,那是新時代攝影剛興起的時候發行的。乍一看我們都覺得它只是一些很普通的照片拼到了一起,主題也不怎麽明晰,感覺沒有什麽太大意義。然而當我們深入了解後,我們發現,那本書的發行時間剛好是改革開放初期。在那之前,你沒有個人的自由,你只能做那些國家讓你去做的事情,而突然間你擁有了自己思考的權利,你會帶著滿腹的好奇心去探索所有你想探索的東西。當我們把這一本看起來沒什麽意義的攝影書集拼到整個歷史脈絡中的時候,它忽然就有了意義。所以說研究中國歷史對我們的工作非常有意義,同時我們也請了許多國內外的學者在書中介紹攝影書集背後的故事和歷史事件。

ART.ZIP: 更深入的了解有沒有改變你對中國的認識?

MP: 完全沒有,它們反而讓我堅定了過去腦海中的中國形象。不過在深度上的確加深了許多,而且你會發現它是沒有止境的——我們至今還在不停地搜羅更多的攝影書集,有更多我們沒見過的書在等著我們去發現,去挖掘。

ART.ZIP: 有沒有想過西方讀者/觀眾在讀這本書或觀看這個展覽的過程中會用東方主義的視角,把它們當作一些奇觀來看待呢?

MP: 完全不會擔心這個問題。我們囊括了許多來自中國的攝影書集,也囊括了許多外國人編輯的關於中國的攝影書集,視角的設定本身就是雙向的。在攝影書集研究史上,我們同樣研究過其他國家的攝影書集,日本、印度、非洲、拉美。這是一個更為宏觀地理解攝影以及各事物內在聯繫的過程。

ART.ZIP: 作為一個西方人,你認為中國和西方世界在攝影書集的制作傳統中有什麽異同呢?

MP: 它們當然有相同的地方。新時代的攝影師在制作非常棒的攝影書集,而這是我在二十年前完全無法想象的。當然,中國的攝影書籍帶有更多的政治色彩,因為國家會監管出版物的內容,而這在西方是不可能發生的。這大概就是兩者之間主要的不同點吧。這種政治控制也對我們的出版物以及展覽造成了很大影響,我們在中國的展覽中甚至不能提到天安門,那可是中國當代史中最重要的一部分。但是這段歷史被抹去了,所以我們自然也不能提。

=======

中國的政治審查的確給這個展覽帶來了很大影響。在過往的幾個展覽中,策展人調整了北京的展覽的內容,有關“天安門”的部分都被刪去了:而他們也不得不為自己的著作《中國攝影書集》推出“大陸版本”。而政治與攝影書集之間扯不斷的聯繫,也正好同他們對攝影的觀點相契合——攝影是永遠無法純粹的,它永遠為達成某種目的而被人們所利用。

ART.ZIP: 在策展的過程中應該有作過很多妥協吧?

TW: 我們的確是需要妥協,但另一方面我們還是需要盡可能去爭取一些東西,因為如果這次我們不去爭取,之後就更沒有機會了。然而如果不作任何妥協,或許連在中國展出的機會都沒有了。如果一個關於中國的展覽無法在中國展出,會是很可悲的一件事。我們不希望只到中國去,把一些東西帶出來,然後只向西方展示。能看到中國人自己同這個展覽之間的對話,會更有意思。從某種意義上來說,這也正是我們在展覽和書中都在探索的一個問題,即政治審查是如何運作的。除了天安門事件,林彪也遭遇了同樣的命運,他的圖像都被從攝影書集中抹去了。而偽滿洲國在當年日軍侵華的時候也做了同樣的事情,對真實的歷史絕口不提。

========

正如展覽所指出的那樣,攝影書集在中國人的生活中隨處可見。然而在國人的生活中,它們被選擇性地無視了。一些人因為一些攝影書集扮演的角色更多地是政治宣傳品,而非藝術品而無視它們。然而今天,當我們重新用另一種角度去閱讀這些書籍的時候,它們忽然重新擁有了自己的價值。

MP: 並沒有任何人了解中國的攝影書集史,就連中國人都沒有人了解。有人了解它的一部分,或是文革時期攝影書集,或是新時代攝影書集,可是從沒有人把它連成一個整體來看,更別說去做這樣的一個收集工作。即使在中國的國家圖書館也有許多書集沒有被收錄,比方說日軍侵華戰爭中編錄的那些書,還有新時代先鋒攝影師們的那些書。他們的收藏中大部分是政治色彩比較濃厚的攝影書集。

TW: 許多攝影書集收藏機構都不收集政治性太強的影集,他們都覺得那不是藝術,只是政治宣傳的工具罷了。我試想了一下如果我也是經歷過那個年代的人,我應該也不會願意去讀那些書。然而如果你試著少一些代入感,以旁觀者的角度去看那些書,去思索攝影是如何被話語權的掌控者所利用,你會從中對媒介,對歷史有更深刻的認識。這也正是我們這本書想要探討的一個重要問題。也許至今中國還無人踏足這個領域的一個重要原因就是國人距離自己的歷史太近了。有時候人們是需要通過旁觀者的眼睛才能看到自己的美的。而當你越深入一個東西的時候,你越能夠發現其中的美。但如果你帶著偏見去看那些作品,覺得它們都是你不願意去了解的那個歷史時期,你就無法發現那種美了。這個世界喜歡向前看,如果你永遠不回頭,不鉆進那段歷史,你就永遠不會理解它的美。如今中國人對攝影書集的重新審視,也讓我想到了你們對陶瓷態度的轉變。不久前,我的一位北京朋友同一位中國收藏家一起來到倫敦,在拍賣行高價買下了一些中國瓷器。那些瓷器正是在二十年前以低價從中國收購來的。這或許也是我所說的“旁觀者清”的又一個例證吧。