TEXT BY 撰文 x KE QIWEN 柯淇雯

IMAGES COURTESY OF 圖片 x FOREST FRINGE 森林藝穗節

‘Every year there’s a moment and the moment goes like this.

You are inside in the hall and it’s getting quite late and quite dark and we are moving chairs. We are forever moving chairs.’

-- Andy Field & Deborah Pearson

“每年都有一個這樣的時刻:天晚了,也很黑,小禮堂裡,我們在搬椅子。我們一直在搬椅子。”

——安迪·菲爾德 & 黛博拉·皮爾森

It’s 2006, Forest Fringe initiated at the Forest Cafe in Edinburgh, a beautiful decaying church hall above the cafe is the place where the group of artists making space for risk and experiment. Over the years they devote themselves to the UK contemporary experimental performances with full of passion. This is a totally independent non-for-profit community, in this community where artists and audiences have no boundaries and even shift the roles; meanwhile this is also a performence festival held annually in Edinburgh, now the festival has grown, they begin to experiment beyond Edinburgh creating projects across the UK and internationally. As one of the UK-China Year of Cultural Exchange programmes in 2015, seven artists came to China to share their ideas with local artists and audiences. After this three-week China Tour, the co-director Andy Field and the artist Richard DeDomenici shared their unforgettable experience with us.

2006年,森林藝穗節(Forest Fringe)起源於愛丁堡一家名為“Forest Cafe”的咖啡館,樓上的舊教堂是這群邊緣藝術家們逐夢的起源地,多年來他們憑著滿腔熱血進行著英國當代表演藝術的探索實驗。這是一個非盈利的獨立藝術社群,在這個社群裡藝術家與觀眾沒有界限甚至可以身分互換;同時這也是一個表演藝術節,每年定期在愛丁堡舉行,如今他們的聲勢越來越浩大,探索的足跡已經遍佈全球。作為2015中英文化交流年的重要項目之一,成員們首次來到中國與當地藝術家和觀眾分享他們的藝術理念。在結束了為期三週的中國之行後,ART.ZIP邀請了聯合創始人安迪·菲爾德(Andy Field)和藝術家理查德·德多米尼奇(Richard DeDomenici)與读者分享這次難忘的經歷。

Andy Field: Incidental Plays

安迪·菲爾德:《偶發表演(Incidental Plays)》

ART.ZIP: It’s quite interesting that Forest Fringe is described as a “fringe of the Fringe”, what makes it so special?

AF: So I suppose people have often called Forest Fringe a “fringe of the Fringe” which I think is like history repeating itself. If you look back at the original history of the Fringe Festival, it began as this the event where artists did this thing that no one gave them permission to do, they just came and arrived in order to make the most of this big prestigious Edinburgh International Festival. It was totally independent, totally autonomous, and maybe slightly cheeky with a bit of a radical spirit to it. They made a space and an opportunity for themselves. That was the original spirit of the Fringe, but you look now, however many years later, and understandably the Fringe has become something very different. It is now so many times larger than the original festival. It is like Edinburgh is all Fringe, with this tiny festival in the middle. So there was a sense in which Forest Fringe was trying to renew some of that spirit of outsiderness, of independence. Doing things without permission, doing what you decided to do, making a space for yourself, not because someone told you to, or because someone gave you permission to do so, but because you have the self-possession to be able to do so. If you want to, if you believe in yourselves, and if you have a community, you can use that community to create that opportunity that you feel you need or deserve.

ART.ZIP: Forest Fringe is more like a community rather than an organization. How did it evolve this way?

AF: It’s very interesting, Forest Fringe began not as a business or business plan or any particular strategy, but rather as an opportunity. The reason Forest Fringe started, in 2007, was because someone approached my co-director Deborah Pearson with an offer of a café and a beautiful church hall above the café and they said: “We have this whole performance space, do you want to do something during the Fringe festival”. So Forest Fringe was born out of this opportunity and this space, and the question of what we wanted to do with it. So for that reason, right from the beginning there was no sense of strategy to what we were doing, and any sense of us as a business was not central to what we were doing. What was central was the active gathering and this act of bringing people together. I think that act of gathering has always been what brings together a group of artists to form a community even if very temporarily and that has always been the essential element of Forest Fringe. That’s been very useful in terms of us reminding ourselves that we are never the most important thing, it is always about the artists and that sense of community, those moments of gathering.

The best way that we have been able to do that is by cutting out as much as possible the sense of Forest Fringe as a business, by reducing our fixed cost base and reducing any administrative burden. This allows us to exist almost entirely in those moments where we come together, and we aren’t worrying too much about trying to develop or sustain an organisation or institution. I think that is our true strength and it allows us to do things that more formal, more traditional organisations cannot.

ART.ZIP: Forest Fringe reminds me of the movement of Fluxus, prior to it artists performed separately and irregularly, whereas you and Pearson have gathered them all together. What is the power and influence that Forest Fringe gives to others?

AF: I really like that reference. The projects we initiated with Forest Fringe had a self-conscious relationship with that group. We made a project a couple of years ago called Paper Stages, which is a festival of performances, disguised as a book, where each page in the book is a different performance for you to make yourself, may it be an event score, serious instructions or a script. In that we were very deliberately borrowing from some traditions Fluxus created like their “do it yourself” performances and events.

However we also try to do something with Forest Fringe that was significantly different to Fluxus. In Fluxus, there were a few artists in the centre, like George Maciunas, who really saw themselves as agitators and provocateurs and who challenged and encouraged the artists in very specific ways through manifestos and creating different ideas of what they should do. I think the approach of Deborah and myself has always been more about trying to create the kinds of spaces where artists can decide for themselves what they want to do, so it’s much less penetrative, less direct and much more about just holding open a space for possibility and self-generation. We challenge artists through the kinds of spaces we create, we often try to be quite playful, quite collaborative, quite autonomous and sometimes quite messy and experimental, and so I suppose the artists that get drawn in are the artists for whom that kind of spaces is appealing. So it becomes a self-selecting community that inspires each other, not by following the manifestos, but through the shared appreciation of the kind of spaces we’ve created.

ART.ZIP: As a co-director of Forest Fringe, were there any particularly interesting or challenging things that happened to you in China?

AF: Everything was interesting in a good way. The most delightful thing to us was engaging with the Chinese audiences we met, because a lot of works are quite humorous and playful, with particular English qualities such as being serious through jokes or being simultaneously playful and serious or even being humorous, but also meaningful. In Britain, the way we think and talk to each other, whether serious or sad, it is always wrapped up in this language of comedy, so we had no idea how the audiences would relate to this particularly peculiar English form of comedy, this slightly surreal and eccentric way of doing things.

So I was most surprised as to how much the Chinese audiences understood this humour implicitly, that they shared that sense of humour and were willing to play along. You could watch it in the way that people related to the Hunt & Darton café, the artists would come and do these strange performances at your table where you were ordering food, but receiving a performance. In a very pretend and non-serious way, the audiences responded naturally: ‘how was your meal?’ ‘I didn’t really like it.’ ‘I wasn’t hungry.’ There was a shared understanding there despite the cultural and historic differences and it surprised me to find they shared this sense of humour to such a great degree and that it translated so well.

The most important challenge was that we tried to create a space in which the kinds of activities we were doing was accessible and understandable for Chinese audiences. So the most interesting part of the project was the conversations that happened around the work. As an example, a relatively simple 17-minute dance piece Someone Something Someone, produced by Neil Callaghan and Simone Kenyon was performed by Simone and dancer Maria Sideri, in almost every venue it generated a spontaneous 40-minute discussion where everyone would sit together and talk about what it made them feel and why they made these decisions.

ART.ZIP: As an artist, is there any connection between your text-based works and Paper Stages?

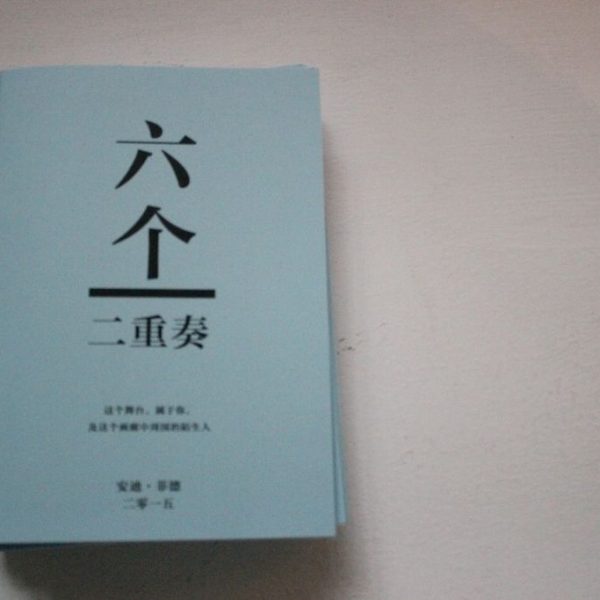

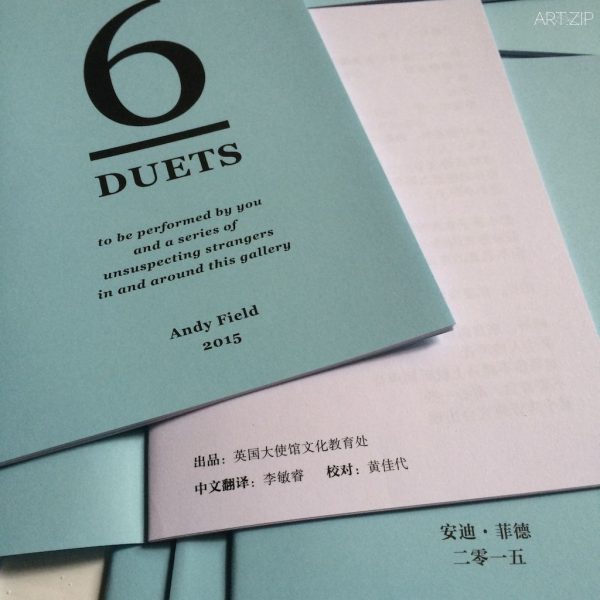

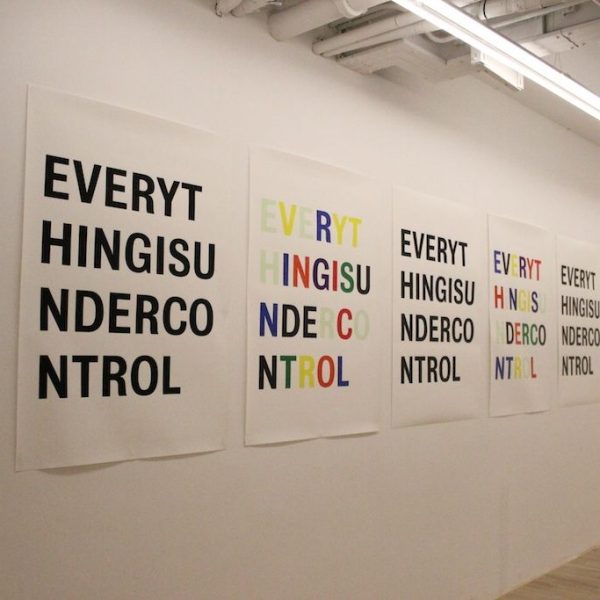

AF: Yes definitely. When we made Paper Stages, I was looking back to the 60’s with the avant-gardes and Fluxus event scores and particularly the work of George Brecht. I liked those small actions and instructions, but I wanted to take that form and do something more contemporary with it: by bringing in some sense of the qualities of narrative and character and create these ambiguous pieces that existed somewhere between an instruction and a poem, somewhere between the possibility of imagining these events taking place and the opportunity to actually perform. I like creating this text while not really knowing what it was, the form remaining elusive. So I started making these pieces called the Incidental Plays for Paper Stages, which could be performed, or were equally powerful as a purely imaginative idea.

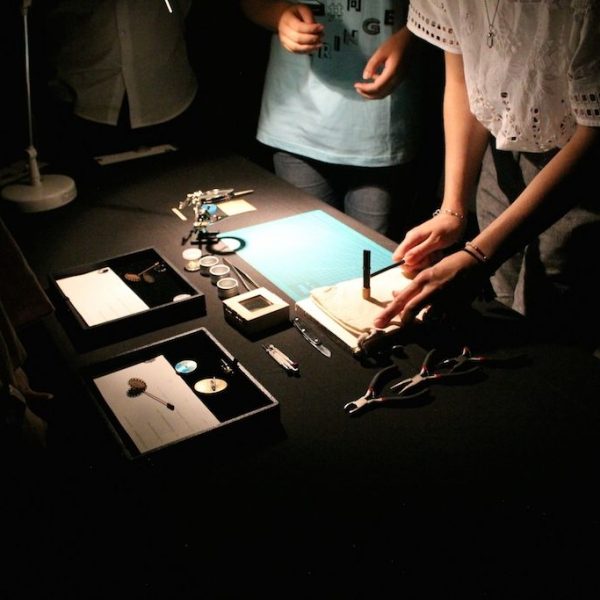

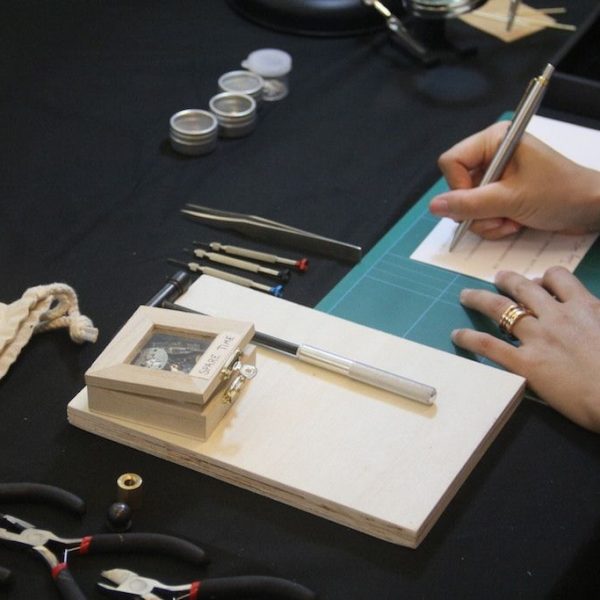

When it came to China, I wanted to again create a piece that operated like that. I was thinking again about the gallery space, the 60’s minimalist work and trying to create a piece that was entirely about your relationship to the other people around you in the gallery but without them directly knowing. So I tried to build on the ideas that I started to explore in Paper Stages, but create slightly longer pieces like instructions for a happening. So this was definitely an extension of the work I did in Paper Stages.

ART.ZIP: What did you want to achieve through the transforming of the text to performance?

AF: I’m very interested in troubling or unpicking the boundary between the actual and the imaginary. A lot of my work is about blurring the line between what is actually happening and what is imaginary. A number of my pieces involved the audiences having to pretend to be ordinary people on the street. I like this idea of pushing ordinary people to pretend to be ordinary people, because it disturbs the neat division between what is pretend and what is real. So what I really wanted to do with these text-based works is again to create this confusion or this complication between what is imaginary and what is real.

When you read these texts you are doing so in the real gallery space, and you might be thinking about a real person on the other side of the gallery, but it’s also all imaginary. You don’t need to perform anything, but simply by being in the gallery reading these texts which are describing activities you could perform in the gallery space you’re already complicating the relationship between the real and the imaginary. I don’t mind it at all if nobody actually performs that work, because it’s already in your head, it’s already transforming the way you are looking at and thinking about the world even without you doing anything. Generally I try to hide when someone is reading the text, so as not to have responsibility and so I can also relinquish control. The less that I know about what’s going on, the more freedom that gives people to make it feel like this is a performance that belongs to them. That is the most interesting thing to me.

ART.ZIP: You mentioned the issues surrounding international cultural communication, what do you think are the key points or difficulties of this communication?

AF: I think that listening and truly understanding is a key difficulty. Sometimes people including myself aren’t really listening to what other people are saying as they have already made certain assumption about what that person is going to say or what that person’s intentions are. It can be difficult because you feel like you are having a conversation with someone, and understanding each other on the superficial level, but there is no deeper comprehension of what both of you actually saying. That’s why I really enjoyed the moments of deep discussion with the Chinese artists. I remembered a Chinese artist who said her English wasn’t very good, but it didn’t matter and because she was able to explain what she meant in a slow and precise way, we really listened to her. I think that’s important, those moments when you are really listening to people are quite rare.

ART.ZIP: 常有人形容森林藝穗節“比藝穗還藝穗(fringe of the Fringe)”,為什麼它的特點如此鮮明呢?

AF: 人們之所以這樣描述可能是因為森林藝穗節重現了歷史吧。早年很多藝術家們的表演得不到官方認可,他們只好藉著聲名遠播的愛丁堡國際藝術節(Edinburgh International Festival)在周邊進行完全獨立、自發的表演活動。聽上去似乎有些厚著臉皮了,但他們畢竟在這個擠破門檻的藝術節期間為自己博得了一席席位。這就是愛丁堡藝穗節(Edinburgh Festival Fringe)的由來。的確經過了這些年,它的轉變和擴張都是合乎情理的,但是如今它卻變成了愛丁堡慶典的中心,反而國際藝術節被擠到了邊上。這是非常遺憾的,因為“邊緣化(Fringe)”這個最初的精神被淡忘了。森林藝穗節就是在試圖延續這份精神——不需等待發號施令,做自己想做的事,另外,當然也是因為我們這群藝術家並不介意“局外人”這樣的身份。我們堅信如果有追求,如果相信自己,如果有一個獨立的藝術社群,那麼一切都是充滿希望的。

ART.ZIP: 看起來森林藝穗節的確更像是一個社群而不像組織,可以聊聊它的發展史嗎?

AF: 森林藝穗節的誕生並沒有任何商業計劃或者策略,而是一個機遇。2007年的時候,有人向我的合作夥伴黛博拉·皮爾森(Deborah Pearson)提議,是否願意在愛丁堡藝穗節期間做些表演活動,他們可以提供表演空間。帶著很多對未來的不確定,Forest Café成為了森林藝穗節誕生的起點。商業和策略之類的並不是我們考慮的重心,我們的目的是創建一個活躍的藝術社群,讓大家有一個互動的平台。在我看來聚眾就是我們該做的,即使只有短暫的相聚,但這就是森林藝穗節的理念。我們時時刻刻提醒著自己,藝術家、社群還有大家相聚的時刻重於一切。所以最好的模式就是建立一個非盈利的社群,盡可能減少固定支出和管理負擔,不用過多考慮如何發展和維繫,作最純粹的藝術交流。這就是森林藝穗節的魅力所在,大多組織和機構是很難做到的。

ART.ZIP: 這讓我們想到了激浪運動(Fluxus),你和皮爾森將散落各地的藝術家聚集起來進行藝術實踐。你認為森林藝穗節對他們產生了怎樣的影響?

AF: 非常開心你把激浪運動和我們聯繫在一起。幾年前我們策劃了一個項目叫做《紙上舞台(Paper Stages)》,表演以書本的形式呈現,每一頁都是一段不同的表演指示,有點類似激浪派的事件樂譜(Event Score),指示說明或手稿等內容。其中我們刻意借用了激浪派 “自己動手(DIY)”的行為藝術和事件等等。

當然我們也有很多截然不同的觀點。激浪派是以少數幾位藝術家為主導像喬治·麥素納斯(George Maciunas),他們將自己歸為號召者或煽動者,用宣言和思想引導藝術家。而我和皮爾森更傾向為藝術家創造各式各樣的空間,但盡可能少地干預和參與他們的決定,讓他們在空間裡自由探索,自主發聲。在這個過程中處處都是幽默、互助和自發的行為,當然也有各種實驗和混亂的狀況發生。我們相互啟發和分享資源,久而久之也就形成了一個獨立自主的社群。

ART.ZIP: 作為中國之行的主要負責人,過程中你有遇到什麼特別有趣的經歷或者挑戰嗎?

AF: 全程都充滿了樂趣,特別是我們與中國觀眾的互動。因為作品大多都以幽默詼諧為主,甚至還帶有濃重的英式表達,會以開玩笑的方式來談論嚴肅的事,幽默的同時又一本正經,詼諧卻意味深長等等。不論是嚴肅還是悲傷,英國人習慣用幽默的方式來思考和交流,所以我們不確定當中國觀眾面對這種英式幽默時會作出怎樣的反應,尤其是對那些超現實而又怪誕的作品。但事實上中國觀眾的接受度大大出乎我的意料,他們不僅欣賞這種英式幽默還主動參與。就拿作品《姐妹花咖啡(Hunt & Darton café)》來說,當觀眾點單時,藝術家會上前作些隨性的表演,很多觀眾都會默契配合:“這裡的餐飲如何?”“這不合我的口味啊。”“我還不餓。”等類似地話語,這種佯裝卻輕鬆的回應方式非常地自然。儘管中英兩國有文化和歷史上的差異,但我們之間確實存在著某種默契,中國觀眾竟能把英式幽默詮釋得如此到位。

要說最大的挑戰應該就是創造一個能讓中國觀眾理解並參與的空間。最有趣的部分要算是表演後的分享環節。藝術家組合尼爾·卡拉漢和西蒙娜·凱尼恩(Neil Callaghan and Simone Kenyon) 創作了一件簡易的舞蹈作品《某某某(Someone Something Someone)》,時長17分鐘,由一位舞者和凱尼恩本人現場演出,幾乎每場演出結束後大夥都會有一個自發性的討論,坐在一起分享彼此的感受。

ART.ZIP: 作為中國之行的藝術家之一,你帶去的文本作品和當初的《紙上舞台》有什麼聯繫嗎?

AF: 當然有聯繫。在籌備《紙上舞台》的時候,我特別回顧了60年代先鋒藝術、激浪派事件樂譜、特別是喬治·布萊希特(George Brecht)的作品。那些細微的動作和指示令我著迷,但我只想採用這些形式而已,在此基礎上加入更多當代的東西:加入一些故事性和人物特徵,既可以是一些指示又可以是一首詩,可以在想象中發生又可以真實地被演繹出來。這些文本作品無法界定性質也不會被形式所限制。當時我為《紙上舞台》創作了一系列文本作品,名為《偶發戲劇(Incidental Plays)》。

這次我打算再一次創作該形式的作品,在考量了展覽空間又考慮了60年代極簡主義後,我試圖創作一件作品是關於在展覽空間內讀者與他人之間的關係,但除了讀者本人之外其他人並不會直接知道。因此在《紙上舞台》的基礎上我創作了幾件稍長的,內容類似即興表演的指示說明。這確實屬於《紙上舞台》的延續創作。

ART.ZIP: 通過文本到表演轉換的這個過程,你試圖實現什麼?

AF: 我總是試圖攪亂現實和虛構的界線,我很多作品都表達了這個觀點。比如讓觀眾假裝是街上的路人,讓普通人扮演普通人,我喜歡這樣的點子,因為它打亂了真實和假象的正常判斷法則。因此以文本為基礎,製造現實和虛構的混淆場面是我真正想做也是正在做的事。

當你在展覽空間中閱讀文本的時候,你可能會想象自己正在作這些即興表演,但都只是想象而已,你並不需要付諸行動,因為你已捲入一場現實與虛構的混亂局面當中。是否有觀眾跟著指示表演並不重要,因為它已經存在觀者腦海裡,即便什麼都不做,他們看待世界的方式也正在發生轉變。通常觀眾閱讀的時候我都不在,因為我越少地干預其中,他們就會有更大的空間去感受這場完全屬於他們自己的表演。這才是最有意思的地方。

ART.ZIP: 你覺得國際文化交流中的重點和難點是什麼?

AF: 要做到真正的傾聽和理解是非常困難的。有時很多人包括我自己在內並沒有真正在聽別人說什麼,因為我們會事先揣測別人接下去要說的話或者別人的意圖。當你覺察到你和對方的談話和理解只能停留在表面,沒有深層次交流的話一切都顯得沒有意義。這也是為什麼我很珍惜這次與中國藝術家交流的機會。我記得一位中國藝術家說她的英文水平不太好,儘管說得很慢,但她非常努力地向我們表達她的想法,我們也仔細地聆聽。這真的很重要,真正聆聽別人是那麼地珍貴。

Richard DeDomenici:The Redux Project

理查德·德多米尼奇:《翻拍計劃(The Redux Project)》

“DeDomenici is a prankster and provocateur. Everything he does is done to question and challenge how we think about things.”

“德多米尼奇是一個十足的搗蛋鬼、煽動分子,他所做的每一件事都是質疑和挑戰傳統的思維模式。”

―― Andy Field, co-founder of Forest Fringe

安迪·菲爾德,森林藝穗節聯合創始人

ART.ZIP: How did you start to be part of Forest Fringe? Why Forest Fringe?

RD: In 2006 I was doing my first proper Edinburgh show, and back then, apart from Dr Roberts’ Magic Bus, there wasn’t much venue choice except the big mainstream ones. They all charged lots of money and were quite restrictive in terms of the work: black box space, one hour duration, fines if your overrun, a few minutes to get in and get out, three weeks of shows with one day off. That year, just across the road from my venue, this new place appeared called Forest Fringe. I kept hearing about how they were doing more experimental work, which I was really into. They encouraged artists to do one-on-one and durational performances. This kind of stuff had never been seen at the fringe before, and completely turned the whole Edinburgh model upside down. I thought Forest Fringe would probably be around for one year and never come back, because how could they afford to? But actually they kept returning, because there was a real untapped demand to see something different. With no venue fees artists could take more risks, and operating on a donation system means audiences could take a chance on something new. Forest Fringe was radical, and luckily people were attracted to this, and it’s been growing ever since. Now there are lots of weird experimental venues in Edinburgh, such as Bob’s Bookshop, and I think Forest laid much of the groundwork for this.

A couple of years later I made a piece of work in a tent. I wanted to reject the venue system and instead invite people into my own portable venue. There was a little back garden at Forest Fringe which wasn’t used, so I asked if I could pitch my tent there and they agreed. I think that was my first proper collaboration with Forest Fringe. By this time the British Council were experimenting with staging some of their Edinburgh Showcase work there, and lots of international visitors had already found out about Forest Fringe’s unique way of doing things.

Soon people from all around the world started inviting Forest Fringe to curate micro-festivals, and in 2013 Andy asked me if I had any ideas for a festival in a cinema in Thailand.

ART.ZIP: Your Redux Project is getting more and more well-known, could you please introduce the project to our readers.

RD: The first Redux was made for Live At The Scala, a Forest Fringe micro-festival supported by the British Council held in the largest remaining single-screen cinema in Bangkok. I proposed a very low-budget remake of scenes from a Thai film, in the original locations. I didn’t want to settle for anything too stereotypical, so, after watching lots of movies, chose a popular romantic comedy called Bangkok Traffic Love Story. Some of it was filmed next to the cinema at Siam Station, so was very site-specific. In my remake I played the female lead, which I thought may have caused offence, but actually the reviewer from The Nation newspaper said they preferred my version to the original, which shocked me.

So I made a second Redux in Glasgow, at a very new, very grassroots festival called Buzzcut, started by two young artists to try and fill the gap after the massive National Review of Live Art festival ended. Buzzcut operated on a similar model to Forest – low-budget, but very generous in other ways, and I wanted to support that. The Scotsman gave my Redux of Cloud Atlas, filmed on the streets of Glasgow, four stars, which was noteworthy as they only gave the original film three stars. So again, my Redux had received better reviews than the original. It seemed like a trend, so I became obsessed with discovering why people prefer cheap fake versions of movies to the originals. Since then I’ve made 40 Reduxes, and if I get to 80 will release a book called ‘Around the world in 80 Reduxes’.

ART.ZIP: Could you tell us about any interesting or challenging things that happened in China?

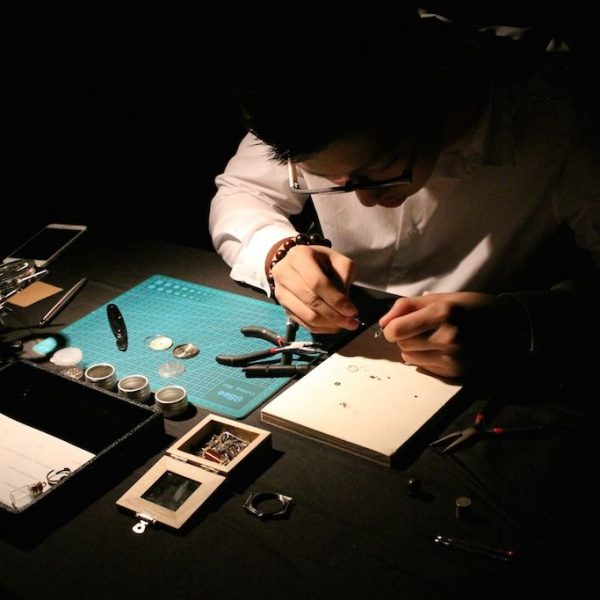

RD: I made four Reduxes in three Chinese cities in two weeks, plus a couple of practice Reduxes in Hong Kong, which is unprecedented, so I spent a lot of time planning beforehand. With limited time and budget, you have to start filming as soon as you arrive. Guangzhou was a great place to start and somewhere I had never been before. I Reduxed the film ‘Inseparable’, the first Chinese movie to star a Hollywood actor, which represented a great coming together of East and West. We worked with the Times Museum who were really amazing and got very involved. They helped find participants, and I was very fortunate to work with Mr. Asia winner Patrick Zhong, who is very famous in Guangzhou, and looks quite similar to actor Daniel Wu. More than 300 people came to the premiere the day after filming, and I suspect many of them were Patrick’s fans!

In Shanghai I Reduxed scenes from the recent Spike Jonze’s film ’Her’ which is set in a futuristic LA and filmed on the Lujiazui skywalks. In Beijing we remade the 1999 Zhang Yang’s film ‘Shower’, which features the Italian song ‘O sole mio’ and is set in the oldest public bathhouse in the city. It’s quite close to the airport and has been repeatedly threatened with demolition, so I was very relieved to find that it was still actually there. Surprisingly they didn’t mind me filming inside, the naked guys with tattoos just continued to walk around in the background. Until this point I’d mainly been working with international arts professionals, so it was nice to hang out with some proper working class people. I think because of this, ‘Shower’ was the most interesting Redux I made in China.

ART.ZIP: Do you have any further plans after your China tour?

RD: The next Redux Project will be produced with the BBC in November. I normally resist co-option into the mainstream. It’s inevitable that the counterculture will be absorbed into the society it critiques, stripped of its political context, and imitated purely for commercial reasons. If every invention eventually becomes convention then it is the job of the artist to keep on innovating.

The Redux Project is a bit different though, because it’s infinitely repeatable and almost designed to be absorbed directly into the culture it critiques, like an antibody in the immune system of capitalism. The project is a comment on the movie industry’s – especially Hollywood’s – tendency towards sequels, prequels and reboots, but I suppose is also a celebration of it. Ironically I hope that by making derivative versions of things that are already fake, that we will somehow arrive at a greater truth. It’s so easy to make our own culture now because we all have movie cameras in our pockets. People have started sending me their own Reduxes. The old hierarchies no longer need to exist.

It’s interesting that the project hasn’t been shut down by Hollywood yet, as all the Reduxes are on YouTube and infringe their intellectual property. Maybe the studios are realising that they can’t prevent people remixing culture, or perhaps they just haven’t noticed me yet.

In China, I was very interested in the notion of “山寨” or ‘Shanzhai’, a specific Chinese term that not only relates to modern times with counterfeit products and the internet but also to something more traditional and old fashioned, with connotations of Robin Hood. We don’t have a word for that in the UK, so I resonated a lot with that concept.

Like Forest Fringe, The Redux Project is just getting bigger and more ambitious. It is never boring – always presenting new challenges in new places with new people. I’ll just keep going until I’m either sent to prison for copyright infringement or invited to direct a Hollywood feature film.

I had lots of new ideas in China, and met loads of great people, so hope this could be the beginning of a beautiful relationship!

ART.ZIP: 請問你是如何開始參與森林藝穗節的呢?原因又是什麼?

RD: 2006年的時候我正在愛丁堡演出,當時只能選擇一些傳統場地,不僅開銷很大,演出的局限也很多。那天我正巧路過看見森林藝穗節,我一直有聽說這個群體在做一些實驗性的藝術項目,我特別感興趣。他們鼓勵藝術家做一對一或者持續時間較長的演出,這些形式幾乎不可能在愛丁堡其他活動中看到,這完全顛覆了那一套陳舊的體制。我本以為他們只會出現一兩年的時間就不見蹤影了,因為經費是個大問題。但事實上他們一年年地壯大,因為不論是藝術家還是觀眾,他們越來越想看到一些新東西。藝術家不需要支付場地費,開放性的樂捐制度也吸引了更多的觀眾。森林藝穗節和主流藝術節走的是截然不同的路,幸運的是觀眾接納這套,如今它的聲勢越來越浩大了。現在愛丁堡出現了很多實驗性的演出場地,比如鮑勃書店(Bob’s Bookshop),我想這應該是森林藝術節奠定了堅實的基礎吧。

幾年後我在帳篷裡做了一次演出,我用這個便攜式的“場地”徹底和傳統的場館說再見。森林藝穗節的所在地Forest Café有一個後花園還沒有人用,幸運地他們同意我將帳篷搭建在那裡進行表演。我想這可以算是我和森林藝穗節的首次正式合作吧!當時英國文化協會(the British Council)正在舉辦愛丁堡前沿劇展(Edinburgh Showcase),許多為之而來的外賓都覺得森林藝穗節非常與眾不同。在那之後,我們陸續接到了全球各大機構的小型藝術節策劃委託項目,2013年安迪還邀請我加入一個泰國的電影節項目。

ART.ZIP: 你的《翻拍計劃》越來越成功了,可以和我們讀者介紹一下嗎?

RD: 第一次的《翻拍計劃》誕生於泰國的一個小型藝術節——斯卡拉現場(Live at the Scala),這是由森林藝穗節策劃,英國文化協會贊助的。場地設在曼谷最大的巨屏影院,我當時構想了一個非常低成本的泰國電影翻拍方案。我不太想作品看起來太循規蹈矩,因此我從曼谷電影中挑選了一部非常主流的愛情片《曼谷輕軌戀曲(Bangkok traffic love story)》。它的取景地正好在影院邊上,這可以算是一件場域特定藝術作品了。我還反串了劇中的女主角,我原本認為也許觀眾會很討厭我這張臉呢,結果當地的國家報刊評價我的版本比原作更高,這確實挺令我驚訝的。

第二次是在格拉斯哥,兩位學生發起了一個草根藝術節名為Buzzcut。雖然他們經費少的可憐,但很多方面理念和森林藝穗節十分相像,所以我決定支持他們。《雲圖(Cloud Atlas)》是我的第二部翻拍,《蘇格蘭人報(Scotsman)》給了我四顆星,這比原版還多一星!也許這是一種潮流吧,我越來越想知道人們更愛翻拍版本的原因。到目前為止我已經完成了40部作品,當我完成80部時我計劃出一本書,名為《環遊世界的80部翻拍(Around the world in 80 Reduxes)》!

ART.ZIP: 在這次中國之行中你有遇到什麼特別有趣的經歷或者挑戰嗎?

RD: 我在兩週內分別在北京、上海和廣州完成了四部翻拍,再加上在香港的幾部試拍,這次的工作量是史無前例的,所以我之前作了很多的準備工作。也因為時間和預算有限,我必須確保萬無一失。廣州是個很好的開始。我翻拍了一部國際大片《形影不離(Inseparable)》,這是第一部由好萊塢明星主演的中國電影,為東西方的融合開了先例。廣東時代美術館(Times Museum)還請來了有名的亞洲先生參與我的翻拍計劃,真的很感謝他們的付出!

我在上海翻拍的是斯派克·瓊斯(Spike Jonze)執導的電影《她(Her)》,而在北京翻拍的是16年前張揚執導的電影《洗澡(Shower)》,取景地是在一處最老式的公共澡堂。這次翻拍的取景地也正是在那,雖然一直有拆遷的傳言,但幸運的是它還在那兒。最讓我驚訝的應該是當地人竟不介意我在他們泡湯的時候拍攝,一個個紋身的彪形大漢大搖大擺地來回踱步。在這之前我都是和藝術專業人士一起工作,但是《洗澡》讓我有機會接觸到當地的普通民眾,可以說這是此行中最有意思的部分了。

ART.ZIP: 未來有什麼計劃嗎?

RD: 我和BBC合作的一部翻拍會在今年十一月面世。通常我不太喜歡我的作品太過主流。但我發現所有反主流文化最終都會被主流社會同化,被剝奪了政治話語,還有各種商業抄襲。如果每個發明最終都會變成主流,那麼藝術家能做的唯有不斷地想新點子。

但《翻拍計劃》又另當別論了,因為它可以無限量複製,直接融入主流文化中,就像資本主義下免疫系統中的抗體一樣。這個計劃是對電影產業的批判,特別是好萊塢,越來越趨於量產化,各種續集、前傳、重拍等等沒完沒了。但其實又算是對電影產業的記錄吧。諷刺地說,我倒希望靠這些“盜版”,人們或多或少能更接近真相。現在我們可以輕而易舉地創造自己的文化了,因為人人都有便攜式攝影機了,我已經陸續收到大眾傳來的翻拍影片,電影產業壟斷的制度已經不復存在了。

但我十分驚訝《翻拍計劃》竟沒有被好萊塢下逐客令,因為我把翻拍作品上傳到YouTube,裡面也有原始影片的對比,這肯定侵犯了知識版權,但卻沒人勒令我停止。這些電影工作室應該慢慢開始意識到他們無法阻止混合文化這件事了吧,也可能他們壓根沒有意識到我的存在。

我對中國的“山寨”或“仿貨”的概念尤其感興趣。它不僅與當下的互聯網還有贗品有關,也和傳統的東西有聯繫。英國沒有這樣的概念,我反而在中國找到了共鳴。

和森林藝穗節一樣,如今《翻拍計劃》的規模越來越大了。時不時有新的挑戰蹦出來,新人、新地點、新電影,我會一直一直做下去,直到某一天我因為侵權而被捕或者受邀去執導好萊塢電影吧!此次的中國之行收穫良多,我還認識了許多了不起的人,希望這是一個好的開始!

- Forest Fringe Fundraising @ The Yard, London 24/05/14 (c) Giulia Delprato – 07510423642