“The head is included in the body, but the face is not…. The head, even the human head, is not necessarily a face. The face is produced only when the head ceases to be a part of the body…”

— Deleuze & Guattari 1

「頭部隸屬於身體,但面孔並非如此……頭部,即使是人類的頭部,也未必成為一張面孔。唯有當頭部不再是身體的一部分時,面孔才得以生成……」

——德勒茲與瓜塔里 1

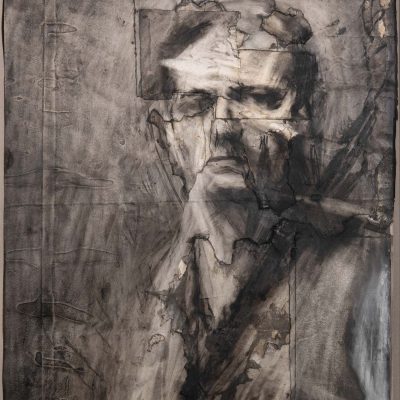

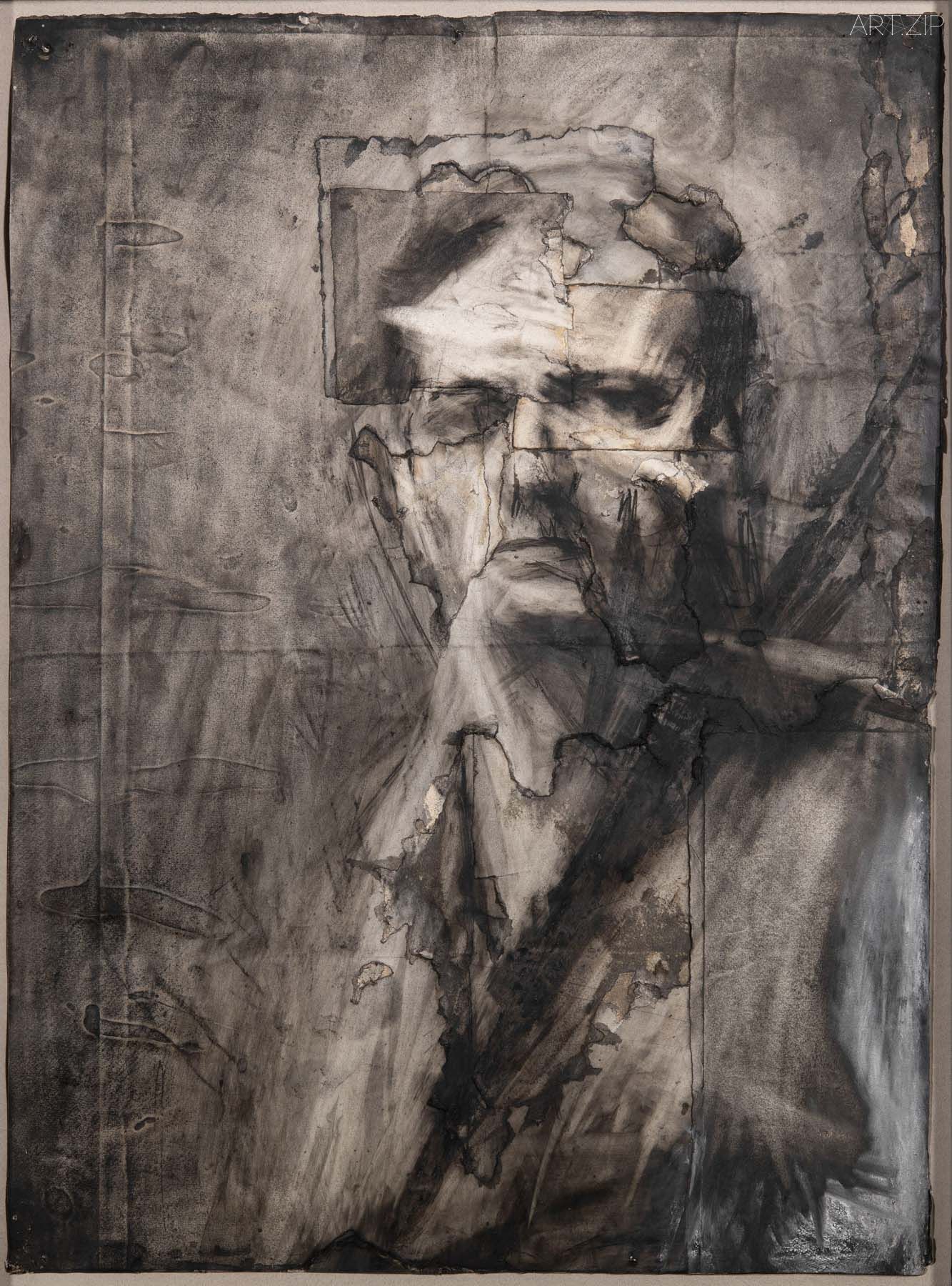

‘Self-Portrait’ (1958) by Frank Auerbach (Photo: Courtauld Gallery)

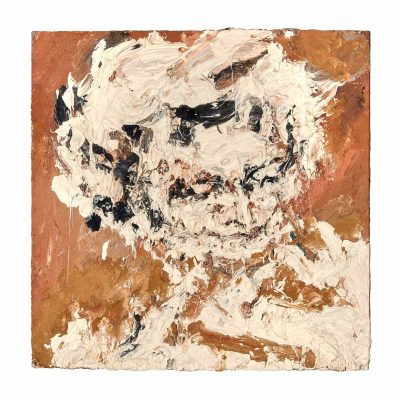

Frank Auerbach asserts that these are not portraits of faces but depictions of heads. Portraits of faces are over coded presentations that open out into the social field with its ritualised repetitions whereas these heads are attracters of attention, even when not necessarily attractive in any given sense. As objects of attention, they belong to no school or manner, they neither move towards an ideal completed form, nor the abstracted dissolution of formlessness, but reside within the oscillation of such contraries. They are the product of accumulated additions and subtractions, but their process of becoming remains obscure, so they resist simulation as they remain within a space of their own distinction. As such they are neither beautiful or sublime, nor abject even, but they might instead be tinged with qualities drawn from each such categories. Rather than aesthetic attribution they have a far more significant set of ethical traits. Each head provides its own evidence of being what it can offer by entering the light of visibility but equally it is also a withdrawal into its own displacement into a placeless place that is invariably called absence or non-being. It is just enough of an offering to be designated a name and location without which it might sink back into a sea of generality and non-identity.

In terms of the history of art when do heads become faces and in turn portraits? In archaic culture we are witness to the depiction of heads. Heads open themselves to forces outside of human particularity, to what might be termed the non-human in the form of gods and spirits. The Romans are a junction point for a clear demarcation of this transition, but local to late modernity this oscillation is still in evidence. When Picasso painted ‘Les Demoiselle’ he painted it with reference to other heads, Egyptian, Iberian, and African heads. These heads served as outposts or intercessors, something impossible to convey through the portraits of faces. Turning though to the milieu of Auerbach, Lucian Freud paints portraits, even though they often map out faces with intensity, David Hockney paints and draws portraits, Francis Bacon paints heads, even despite often assuming mannerisms to do so, but Auerbach distinctively paints heads. There is a brute physicality to these drawings, which evokes the feeling of a process of excavation of raw matter to produce resemblance. Many of these semblances are like continents assembles from blackened dust that accumulate into formations and perforations. Rather than being the continuation of vision, they accumulate the process of interruptions and spacings. The struggle is not just one of producing resemblance but overcoming the fall into the region of the shadow realm where deformation and chaos reigns. In this process there is not just a build-up of layers, reversals, corrections, and eliminations but also a reanimation of the temporal progression of the work itself. Temporality of these works is time lead astray outside the principle of reality. Things are subjected to being taken apart, only to be reassembled outside of the order in which they were given.

弗蘭克·奧爾巴赫(Frank Auerbach)主張,這些作品並非面孔的肖像,而是頭部的描繪。面孔的肖像是一種過度編碼的呈現,將自身敞開於充滿儀式化重複的社會場域中;而這些頭部則作為注意力的吸引者存在,儘管它們並不一定具備任何傳統意義上的吸引力。作為注意力的對象,它們不隸屬於任何學派或風格,不追求理想的完整形式,也不走向抽象的無形解構,而是在這些對立之間的擺盪中找到自己的位置。這些頭部是由不斷累積的添加與減除所生成的結果,但它們的「生成過程」卻始終保有一種難以捉摸的神秘性。因此,它們抗拒模仿,因為它們始終停留在自身獨特的空間中。正因如此,它們既非美麗,也非崇高,甚至不屬於卑賤的範疇,而是從這些類別中提取了某些特質,染上一層模糊的色彩。與其說它們屬於美學的領域,不如說它們展現了一組更為重要的倫理特徵。每個頭部都以自身的存在證據進入可見性的光中,展現出它所能提供的一切;但同時,它也撤回自身,進入一個位移的狀態,置身於一個「無處之地」——一個往往被稱為「缺席」或「非存在」的領域。這種呈現僅僅足以讓它們被命名並賦予位置,否則,它們可能會沉沒於普遍性與無身份的海洋之中。

在藝術史的脈絡中,頭部何時轉變為面孔,進而成為肖像?在古代文化中,我們見證了頭部的描繪。頭部向超越人類個體性的力量敞開,面向諸如神靈與精靈等非人存在。羅馬人是這一轉變過程中的一個明顯分水嶺,但即便到了近現代晚期,這種擺盪仍然留有痕跡。當畢加索創作《亞維農少女》時,他參考了其他文化中的頭部形象——埃及的、伊比利亞的以及非洲的。這些頭部如同前哨或中介者,傳達出面孔肖像所無法表達的某種東西。然而,回到奧爾巴赫的語境中,盧西安·弗洛伊德(Lucian Freud)創作肖像畫,儘管這些畫作常常以極大的強度描繪面孔;大衛·霍克尼(David Hockney)既繪製也描畫肖像;弗朗西斯·培根(Francis Bacon)畫的是頭部,雖然他的作品中時常帶有某種程式化的姿態。但奧爾巴赫則以獨特的方式專注於頭部的描繪。

這些頭部素描展現出一種原始的物質性,彷彿是在挖掘粗礦的原材料以生成相似性的過程。許多這樣的相似性宛如由積聚而成的黑色塵土拼湊出的大陸,這些大陸形成具體的形態,並伴隨著穿孔與斷裂。這些作品不是視覺的延續,而是中斷與間隙的不斷積累。這種創作的掙扎不僅在於生成相似性,更在於避免墜入陰影領域,那裡變形與混沌占據主導地位。在這個過程中,不僅有層層疊加、逆轉、修正與刪除,還包含了對作品自身時間性的重新激活。這些作品的時間性是一種偏離現實原則的時間——事物被拆解,又被重新組合,但這種組合已超越了它們最初被賦予的秩序。

These heads appear to run parallel to the fascination with the war-torn urban landscape of post Second World War London. The city it seems has its own distinct face and in turn a mask. London was called the ‘smoke’ in the 1950’s and early 60’s due to the smog which formed a ubiquitous blanket over the everyday life of the city. So, the combination of this desolation of a decaying structure and the pollution formed a grimy backdrop to these drawings, themselves produced out of charcoal. The light is thus subdued, a half-light in which absence is contested within a space that trembles by virtue of the struggle to endure. It as though the long passage of sitting for sometimes months, reflects the will to endure. Nothing is given in advance of this, just a process of being-with. This being-with is both intimate and remote at the same as if everything might be touched and in turn known mixed with remoteness and not knowing. Both forces are in circulation. Giacometti shares this same characteristic. Both artists appear as condemned to make work without a sign of finality as there is no proscribed destination or horizon. The difference between this condition of condemned thus contrasts with that of melancholia. It is in a region that places itself beyond psychological characterisation even though it might appear as a signifier of it. The fact that in both cases the idea of slowness is readily evoked, but this is a form of slowness that contains rapidly applied marks as constituent presence to capture what is fleeting within duration. The marks in these drawings, are at the intersection of the interior and exterior and replace the chasm of the two with a fold. They exist in order to eat away of the manifestation of time so as not to reside within either slowness or immediacy but on the edge or rupture of temporality the Greeks termed kairos.

這些頭部似乎與二戰後倫敦滿目瘡痍的城市景觀形成了一種呼應。這座城市彷彿擁有一張獨特的面孔,而這張面孔同時也是一副面具。20世紀50年代至60年代初期,倫敦被稱為「煙霧之城」(The Smoke),因為霧霾如一層無所不在的毯子,覆蓋了城市的日常生活。廢墟般的殘破結構與污染交織,為這些炭筆素描提供了骯髒而陰鬱的背景。光線因此被壓制,成為一種「半光」——一種在缺席與存在之間掙扎的空間,仿佛這種持續的抗爭使空間微微顫動。這些長時間的繪畫過程,有時甚至持續數月之久,似乎反映了一種對持續性的堅韌意志。在這樣的過程中,沒有任何事物是預先給予的,只有一種純粹的「共在」。這種「共在」既親密又遙遠,彷彿一切都能被觸碰、被認識,但又伴隨著距離與未知感。兩種力量在此循環不息。賈科梅蒂(Giacometti)的作品同樣體現了這一特質。這兩位藝術家仿佛被「無止境地創作」所譴責,因為他們的創作沒有終點,也沒有固定的地平線。他們這種「被譴責」的狀態,與憂鬱形成鮮明對比。它超越了心理學的描述範疇,即使乍看之下可能似乎具有心理符號的特徵。在他們的創作中,「緩慢」的概念經常被喚起,但這種緩慢並非僅僅是遲滯,而是蘊含著快速筆觸的緩慢。這些快速的筆觸成為作品內在存在的構成部分,試圖捕捉持續時間中那稍縱即逝的瞬間。在這些素描中,筆觸處於內在與外在的交匯點,取代了兩者之間的裂隙,形成一種「褶皺」。這些筆觸的存在,旨在侵蝕時間的表現,使其不再完全屬於緩慢或即刻之中,而是停留在時間性邊緣的裂隙——古希臘人所稱的「契機」(kairos)。

The word ‘subjectile’ is an ambiguous term employed by Antonin Artaud to indicate the interface between a support or surface and subjective manifestation in relationship to this. With this term, Artaud explored the way the paper or the support betrayed him by becoming a projectile that teared away from what it was subjected too. This points to a form of ontological insecurity that the act of drawing can occasion and when witnessing all the scars, tears, rips, and repairs to the surface of many of these drawings, we can become witness to the pent-up energetics invested in them. They can be understood as maps of this process of discharge. The word ‘subjectum’ is the original Latin word for the subject, which translates as ‘that which is pressed under.’ Drawing not only serves to indicate this condition of discovering being pressed under, but is an opposition or release to it. On the level of figuration, it issues an impossible conjunction, like a wound that is constantly being opened. This sense impossibility simply repeats, but in so doing is coupled with forgetting. In this erasure is part of what is made manifest.

Even though these drawings were produced early in his creative life they have the look of a late style. They also attract a relationship to the late style of other artists, and this is especially true in relationship with late Rembrandt. Beside the obvious relationship to a quality of intensity, there is a glow of ‘interior radiance’ that issues from the employment of black or shadow with both. Temporality simply stops signifying when absorbed into blackness. Late is the threat of dissolution. In a text by Helene Cixous ‘Bathsheba or the Interior Bible’ she asks: “Where does Rembrandt take us? To a foreign land, our own. A foreign land, our other country. He takes us to the Heart.’2 This could have been written about these depictions of heads. The head and the heart together. They are works that not only join the head and the heart, but also the void with a strange dignity. Within this strange dignity mixed with the void, a possibility of grandeur is occasioned, but one that is marked also by vulnerability also. As such they are marks recording an ethical encounter which opens out a pure relationship of being with. Those who sit with this must be touched by this sense. This space of encounter is our ‘foreign land’.

「Subjectile」 是一個含義模糊的術語,由安東寧·阿爾托(Antonin Artaud)提出,用來描述支撐物或表面與主觀表現之間的界面關係。阿爾托藉由這個術語,探討紙張或支撐物如何背叛了他,成為一個「拋射物」(projectile),撕裂並脫離它所承載的對象。這種撕裂指向一種存在論上的不安——一種素描行為可能引發的不確定性與張力。而當我們凝視那些滿佈傷痕、撕裂、裂口與修補痕跡的素描表面時,彷彿可以感受到其中壓抑已久的能量正試圖釋放。這些作品可以被理解為這種能量釋放過程的地圖。「Subjectum」,作為「主體」的拉丁詞源,意指「被壓在下面的東西」。素描不僅揭示了這種「被壓在下面」的存在狀態,還化身為一種對抗與釋放的形式。在具象層面上,素描呈現了一種不可能的結合,宛如一道不斷被撕裂的傷口。這種不可能性無限重複,而重複本身又與遺忘交織。在這樣的抹除過程中,部分事物才得以顯現。

儘管這些素描完成於他創作生涯的早期,但它們卻散發出晚期風格的氣質。這些作品與其他藝術家的晚期風格,尤其是晚期倫勃朗(Rembrandt)之間,形成了明顯的共鳴。除了強烈的情感張力外,它們還展現出黑色與陰影運用所帶來的「內在光輝」。當黑暗吞沒一切時,時間的意義也隨之停滯。晚期風格總是暗示著解體的威脅。

在海倫·西蘇(Hélène Cixous)的文本《拔示巴或內在的聖經》(Bathsheba or the Interior Bible)中,她問道:「倫勃朗把我們帶到哪裡?帶到一片陌生的土地——我們自己的土地。一片異鄉,我們的另一個國度。他把我們帶到心靈深處。2 」這句話彷彿就是為這些頭部描繪而寫的——頭部與心靈在其中緊密相連。這些作品不僅將頭部與心靈聯結,還將虛無與某種奇特的尊嚴交織。在這種尊嚴與虛無的融合中,偉大的可能性被孕育而生,但它同時帶有脆弱的印記。因此,這些作品可以被視為記錄了一場倫理遭遇的痕跡,展現出一種純粹的「共在」關係。

那些與這些作品「同坐」的人,必然會被這種感受深深觸動。這場遭遇的空間,正是我們的「異鄉」。

1.Deleuze & Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, P.188

2. Helene Cixous, Stigma, P.6

Frank Auerbach: The Charcoal Heads

The Courtald Gallery

9 Feb to 27 May 2024

Text by Jonathan Miles