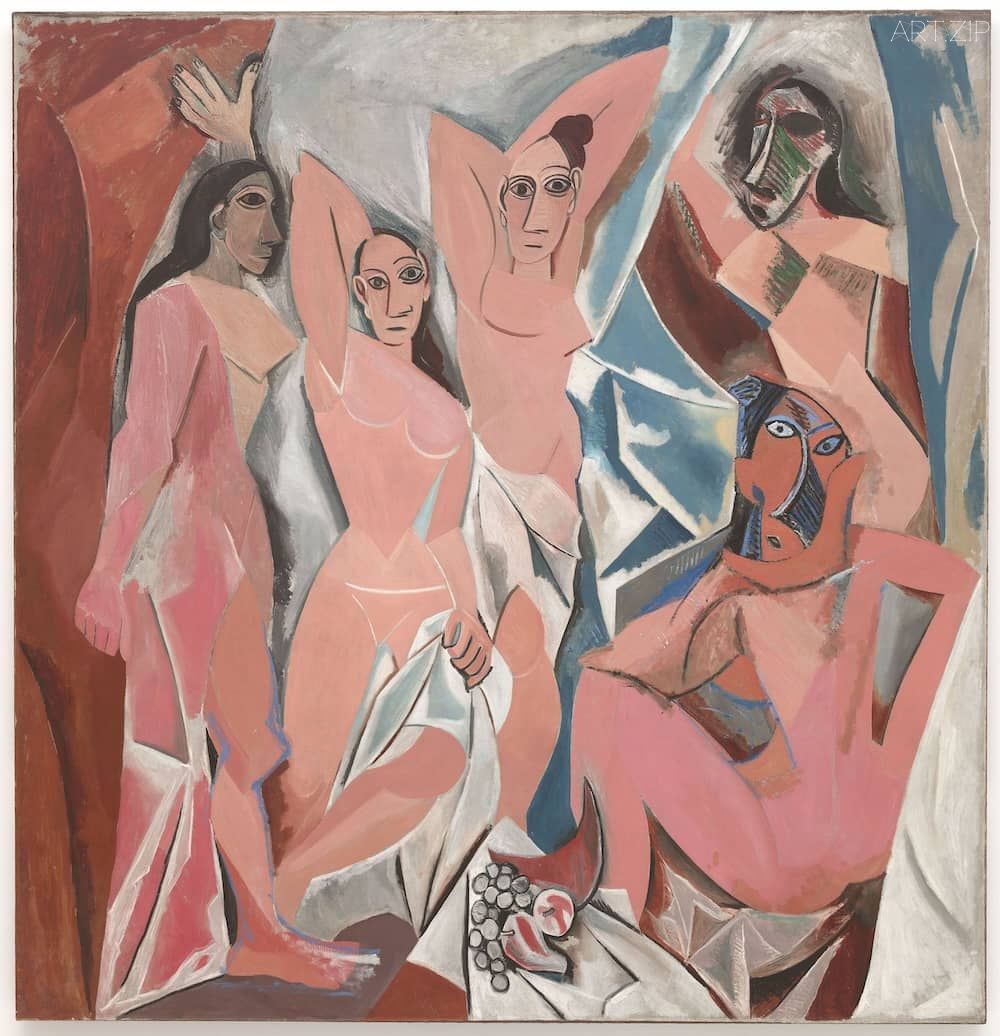

Modernity in the second half of the 19th century formed itself in opposition to tradition as both an aesthetic concept and as social experience. It was understood as a new way of experiencing temporality in the form of the forever new and as such is marked by a permanent state of flux or transition. This implied a lack of fixed values or vanishing point. Within aesthetic practice this implied a continual process of either invention or experimentation as part of the social autonomy of art. The advent of photography served to strengthen the shift away from mimesis in the plastic arts but less obvious was the increased range and lower price of paper and pigments. Works on paper allowed for investigation of partial forms or fragments to become incorporated into the process of realising modes of transformation which culminates in the realisation of Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles de Avignon” that entailed dozens of preparatory works on paper. This in part had been the subject of an earlier RA exhibition (2020) examining Picasso’s work on paper but one with extraordinary range and focus.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907 by Pablo Picasso

The exhibition at the RA of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works on paper as an overall exhibition is vague in its outline because the status of many of the drawing and painting practices differ so much within this generic umbrella. This leads to a choice of direction, either of looking for a special juncture or paradigmatic shift in the relationship of period in the employment of paper, or to look towards the broader impulses that surfaced within early modernism regarding paper, but without privileging this as a passage. In the first instance the search for stylistic traits and figures would appear to be the most viable starting point, these would include the fragment, delicacy, transience, intimacy, fragility, schema, study, becoming, interiority, the minor, and improvisation. Then there would be the search for numerous other issues start to occur due to the instabilities latent in the starting point.

The division of minor and major in terms of categorising works of art is also a problem because of the way it has historical privileged the way this has occurred. Within the late modern period, this privileging has undergone much by way of revision, that results now in works of all mediums being shown as a continuum. The recent Tate Modern exhibition of Rodin is a case in point of this restaging of the entire process of producing work being presented as a fluid encounter of a totality. Another example that might be considered is the relationship between the major paintings of Seurat and his small oil studies and drawings. Rather than considering his drawings as being preparations, are they not a quite separate aesthetic category in their own terms and in that case to be understood as major works regardless of scale or medium. Then we have the case of Redon who mostly work on a small scale and on paper, often in a serial manner but has this impacted on his art historical status? So rather than doing a survey of the entire exhibition, a concentration on just three works might offer another route into the shifts that were becoming manifest. This then opens out the potential for multiple readings to occur because the reading of modernism itself is understood as opening to a multiplicity of signs and impulses.

Georges Seurat executed his main body of drawings between 1880-86 using Conte crayon which is a hard medium made up of charcoal and wax or clay binder. As a medium it does not lend itself to shading and as such it mimics the way that he employed oil paint. Paul Signac described his drawings as “…the most beautiful painter’s drawings in existence.” In his practice Seurat was drawn to rational and scientific ideas of colour theory and perception and yet his drawings have a mysterious quality particularly in relationship to the quality of light that issues from them. In ‘Seated Boy (study for Bathing Place, Asnieres), 1883 there is a subtle rendering of form through shifts in tonality. The drawings appear to emerge out of darkness giving rise to light and the choice of Michallet paper served to emphasize the layering effect that he achieved. Although this drawing was understood as being a study for a larger work, it is in most respects not a sketch but a work in its own right with values not found in the final painting and it is this quality that makes his drawing so enthralling because they introduce something new into modernity, technique merging with meditation on the stillness of the image all of which is touched by a lingering murkiness laying beyond the illumination of everyday, empirical light. This other sense of light is not the inbetween of light and night, but a different illumination derived from a placeless place, a mutation born from the touch of memories captured in ancient Greek carvings or in the acid eating away the black of Rembrandt’s etchings, as if memory might become detached from temporal flux but at the same time be also detached from spectrality. At once so plastic, but a rendering freed from gravity, they are in search of quite other co-ordinates, without either heat or moisture, therefore with nothing that sentiment might attach itself to. If his painting emanate the light of rationality, as if they might be counted and added up, even if exhausting in being so, the parts do add up to a something that is rendered as a seeing of something, even if spliced by anarchist resistance of this being the case. These drawing though differ from this because they have their destination outside of calculation and so in search of another name that escapes the designation of an impression. Another modernity or even the other of a modernity laying in wait. Perhaps like Kant’s description of the schema being a third genus or even simply the third, these drawings are of a modernity of the third kind, a modernity that never arrived because it always stays within a condition of becoming.

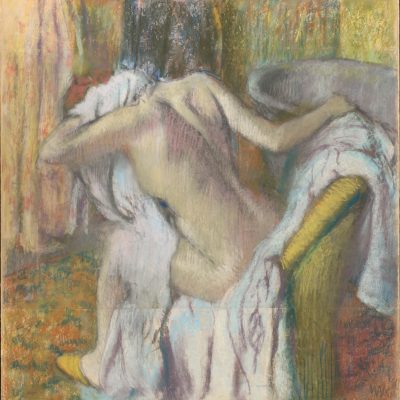

A woman sits at a window. The light inside the room is subdued as if half light that acts as an attracted of the full light of the day. It is a thinking image, or an image that the divide of light produces room for thought, but perhaps the other of thought, ‘il y a’. If so no face can be given to this space of neutrality, so noone can be qute identified. Degas was apart from himself in this, absorbed by what drawing can do do and what must be left undone within this. A close up that loses perspective and is thus without distance, therefore a refracted, diffuse image with nothing much to hang onto. (In contradistinction the potrayal of dancers always have clarity, even if they are a clarity of absorbed thoughtlessness). The image is an arrest that sinks back into it own condition, with all the days expended counted as though weighted by ennui. Outside was the scent of war but this is just a passing image within this, an interval of passage resisting the destractions of the outside.

Symbolism as embodied by this painting ‘The Golden Cell’ by Odilon Redon (1892). It is painted on a guilt ground in oil and coloured chalks. If Impressionism found its orienation in the sensation emanating from sunlight, then Symbolism was of the reverie induced by the night and the unconscious. The blue head in this painting appears to float free of any earthly attachment, radiating in within a guilded space of a void in the beyond. This beyond leads not only to the continent of interiority but also the imaginary of different continents that make up the East. These worlds are coloured differently and thus are able to draw other lines around possible journeys. Rather than being a painting of its time, it takes a step outside of it, not as an avant-garde impulse as much as being ‘out of tune’ with the category of reality. The image comes to a standstill shedding the restlessness of the present in order to begin another type of procession and with this redistribute the relationship of time and the image. This is what enables the image to ‘withdraw as phantom’ and to become another mode of succession.

Modernism was never a singuluar mode of development but was much closer to a coiled spring whose latency derived from contrary forces assembled from within its matrix that manifests as rhythmical patterns and impulses. In this way Modernism might be read as a series of stoppages, striations, and arrests as opposed to one of completed transitions, progressions, and continuities. This is to record a shift toward acknowedging that art has become only “a vestige of art – both an evanescent trace and an almost ungraspable fragment,” a sign of that “the history of art is a history that withdraws at its outset and always from the history or the histrocity that is represented as process or as “progress.”

When a history is being presented we can grant it its passage as completed idea but instead let this passage be reconfigured in different shapes outside of its schematic contour. This is mirrored in these three works were the privileging of drawing as an act contour is overturned in order that the lines of inside and outside might reconfigured. Modernity was just the possibility of such events occurring.

We are simply left, not with a ruination of modernity, but its fragility, like the reality of these works on paper.

Impressionists on Paper: Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec.

Royal Academy of Arts

Until 10 March 2024

Text by Jonathan Miles