“Beauty and the devil are the same thing.’–Mapplethorpe

Time has now lapsed since his premature death (1989) so we might be inclined to ask if a survey show such as this might shed a new perspective on his work, or does it just serve to cement his already consolidated profile. Certainly, there has been no attempt to re-edition his work on a more spectacular scale, nor to present an altogether revised portrait of potential aesthetic reconfigurations. There have been numerous exhibitions and publications that have sought out singularities in his work: portraits, flower studies, erotic or fetish worlds, body building narratives, with each of these genres or clusters giving rise to an exact aesthetic sensibility drawing upon both Classicism and the Baroque alongside Modernist photography. By citing both Classicism and Baroque as sources of stylistic influence, an open play of difference is made manifest, for instance between staging and theatricality, intimacy and distance, formality and exaggeration, discretion and excess, beauty and abjection, fetishism and clarity, seriality and singularity, refinement and transgression, fascination and fixation, and exactness and the fragment. This play of difference also opens out a complex artist forming a body of work in conjunction to his life and milieu. Quite different worlds are in turn made available through his work, for instance, that of a chronicler of the personas of the New York art world, a recorder of the underworld of S/M clubs, depicter of flowers, still lives, a constructer of self-portraits, and studies of nudes and bodies. All of this points to a figure that is much more complex than that of an aesthetic formalist serving as an umbrella for his overall relationship to his work.

There is the exposure of work that has not been shown to a viewing public before. These consist of still lives and some portraits, but nothing that might disturb any of the prevailing critical views. The hanging of the work is not really resolved and the large cluster of portraits on a single wall militates against a more sober reception of these works which far more considered spatial intervals. Something about the formal qualities appear to demand a conservative presentation. This is not to claim that his work has a conservative underside but that its formal qualities have a sober reserve embedded within its structure. Even his erotic photographs work by virtue of a tension between the nature of the subject and the organisation of compositional elements. This implies a careful arrangement of forces that constitute the image, rather being an outcome of just a good eye or technical facility even those these attributes are clearly present.

Rose, 1989, ©Robert Mapplethrope

Although most of his work is black and white, there is a stunning collection of colour images in the form of studies of flowers. As images they embody a form of saturated radiance that present a condition of excess. This partly explains why they might be read as erotic going beyond their literal representational frame to touch another inscriptive circulation. Whereas Dutch flower paintings of the 17th C show blooms at their visual optimum, whereas the elegance of these works capture a state of becoming other within a very short interval. The object turns into a subject on the level of its imaginary. Within this state of fascination, the image trembles on its edge, with a sense of drama that is implicated within this, a quality that first surfaces within the Baroque period. When Kafka stated that: “We photograph things in order to drive them out of our minds,” he captured the ambivalence inherent in the relationship to the image. The incline of the image is first to appear but that this contains the seed of another incline, and that is one of dissolution.

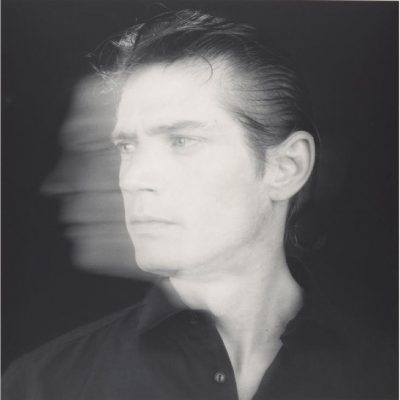

In his essay ‘The Line and the Light’ Jacques Lacan discusses the relationship of the eye to the subject and argues that contained with the geometric dimension of vision, the object of vision catches the subject in its trap. We might imagine that the picture we construct is made up of straight lines, but light is instead refracted. For the photographer what the lens sees and what the eye is witness to, is in perpetual conflict because of the implied lack of symmetry between the appearance of the object and how it projects itself. Lacan captures this difference in the statement: “You never look at me from the place from which I see you.” This tension is partly conceived by Mapplethorpe as being central to erotic depiction because of the way that it alters or reconfigures the position and the constitution of authorship. The line traversed in relationship to the erotic and the pornographic is less to do with appearance, rather it is related to a collapse of distance which is authorised in relationship to the apparatus of vision. With pornography the subject of perception and the object of attention collapse into an abject state that resides neither in object nor subject, whereas in the erotic occasions the limit of the subject threatening the dissolution of the object. The erotic then, either passes over into the death drive or sublimates into the beautiful and this articulates the difference between subjective striation or the free play of the faculties, but which ever, is an intensification on the level of subjective encounter. Thus, Mapplethorpe appeared to criss-cross over such boundaries, in part as a response to an inaugural tension within image presentation understood as the drama between intimacy and distance at play within his aesthetic predilection. He never quite resolved a desire to still the image nor his predilection to indicate restlessness that propelled that desire, and that this schism captures the relationship on an abstract level between the death drive and eros. He seemed to grasp a relationship to this conflict when we talked about losing himself when placed in front of the camera in a similar way of losing himself when having sex. It was in such a state that the unexpected might occur both in life and in art. What defined him as an artist was being able to look both ways within short intervals of time and create a mediation on this.

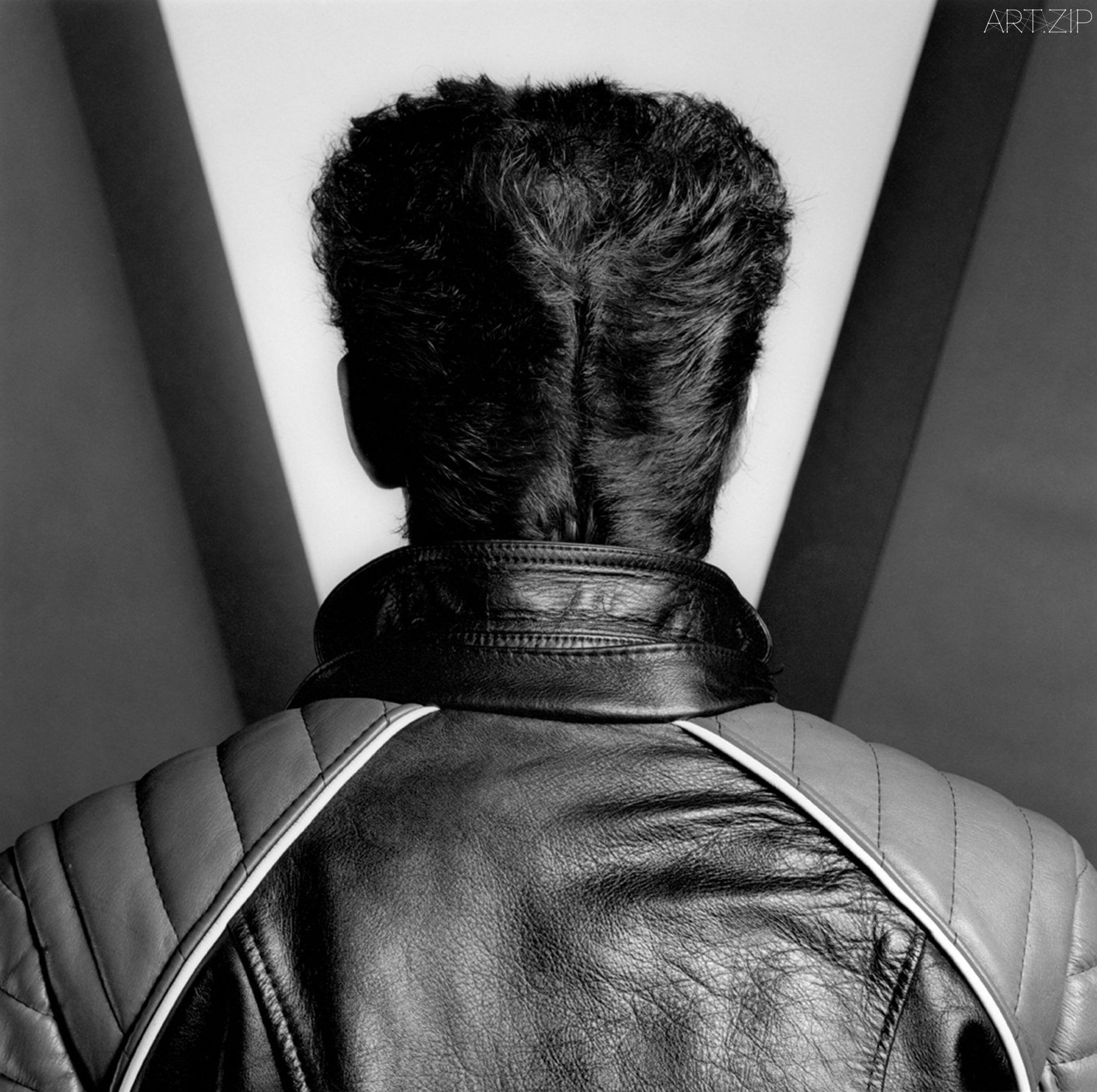

In a ‘Self Portrait’ (1981) he turns his face away from the camera and instead photographs the back of his head. It has a formality to it, as if casually part of a sequence, but it is also an image that arrests and thus stands out as a special way of being alone. As an image it takes a leap into the unknown. The image of the ‘Rose’ (1989) might be understood as an epitaph but also as an affirmation of aesthetic harmony. Both images have a face, even if in a state of disavowal in presenting a frontal or direct showing of it. There is always a blind spot within the image, something that cannot be shown, no matter how inventive the relationship to presence. Mapplethorpe’s work is haunted by this lingering perception in which the feeling of theatre is ever present.

Robert Mapplethorpe: Subject Object Image

Alison Jacques Gallery

Until 20 January 2024

text by Jonathan Miles