Text 撰文 x by Joshua Gong 龔允之

Jenova Chen was a video game producer, born in Shanghai and now working in the US. The games he made were conceptually avant-garde, and in 2008 he was nominated by the MIT Technology Review as one of the top 35 innovators in the world under the age of 35. In spite of his technological education forcedly set by his Chinese parents, Chen has always wanted to be an artist. He realised such a dream by making artistic digital programmes that expressed his aesthetic and philosophic ideals. This article will try to analysis the relations between Chen’s art and the Post Digital Era, through three aspects: Art History, Psychoanalysis and Museology.

陳星漢是一位出身於上海,現居美國的遊戲製作人。他所製作的遊戲由於其前衛的互動理念被《華爾街日報》等媒體譽為“禪師”。2008年他被《麻省理工科技評論(MIT Technology Review)》列為35歲以下世界最有影響力的35位創新者之一。[1] 他自小酷愛藝術,可他父母卻希望他學習理科。[2] 被迫走上計算機編程道路的他卻成功地通過數碼程序實現了藝術的夢想,通過數碼手段闡釋了他對藝術和哲學的理解。本文旨在從藝術史、心理學和博物館學三個方面來分析陳漢星的程序與後數碼時代藝術的關係。

Digital Art and Post Modernism:

In discussing the Post Digital Era, Post Modernism is inevitably involved, no matter how vernacular it appears nowadays. Post Modernism has become widely used since the 1980s; and not only had it questioned the traditional linear historiographies, but also blurred the boundaries between different art media. From a conservative view, Jenova Chen, as a game producer, cannot be qualified as an artist. Ironically, his work, in the field of video games is thought to be art, a great experience rather than a serious game, due to its avant-garde concept. Traditional games whether focused on controllability (e. g. Super Mario series), or narrative-effects, like a film (e. g. Final Fantasy series). Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear Solid series was a rare high quality game that fully presents those two elements. Even though Kojima was regarded as talented as a great film director, his game was heavily influenced by film. Only until digital games could justify its unique experience that traditional arts (painting, sculpture, film, literature, choreography etc.) failed to provide, could it claim itself as the Ninth Art. Chen’s work presented the essence of digital art that has never been fully articulated before.

He made Cloud, Flow, Flower and Journey, and none of which emphasised on controllability or narrative. The naturalistic visual and easy listening music conveyed a therapeutic experience to the participants. Digital art presents its own idiosyncrasy: spontaneous and dynamic interaction with the audience. In the light of this innovation, traditional viewers of art transcended to interactive participants.

Moreover, Chen can also be regarded as a contemporary artist, because his work explored the critical issues in contemporary society. His observation, like many avant-garde masters, is acute and ahead of time. For example, Cloud elucidated his anxiety caused by air pollution. It was produced in 2005, and was based on his childhood memory: he was in a hospital in Shanghai due to asthma, dreaming about flying above the skyscrapers freely inhaling fresh air. The game was set in a scene consisting of blue sky, white clouds, and green islands. The participants would control a flying boy collecting and interacting with white clouds and purify the polluted environment. When he arrived in the US, Chen was sad to see the difference between the skies in the US and Shanghai. The game reflected the critical issues caused by Modernisation, Industrialisation and Urbanisation. Chen’s satire on the Chinese environment was prophetic, because the smog problem in China had not become apparent until 2010. Chen regarded himself as an artist and he stressed on such an identity by comparing with famous directors such as Steven Spielberg and Hayao Miyazaki. Chen said:“Deep down I feel I am still an artist, wishing to make things and share. Even though my major is computing, for me it is just a suitable approach to art.”

數碼藝術與後現代主義:

談及後數碼時代,不可避免地要提到“後現代主義”的濫觴。後現代藝術理論在80年代開始不僅在西方大行其道,而且與中國的新潮文藝也淵源頗深。美國文化學家詹明信於1985年在北京大學進行了為期四個月的講學。他的講學內容便是1987年出版的《後現代主義與文化理論》(中文版先於英文版幾年),是後現代主義名著。1985年勞申伯在中國的展覽引發了中國藝術界對後現代主義以及新媒體和技術的討論。[3] 在85新潮發展後期,中國的藝術家和理論家已經開始關注後現代理論,然而當時較為統一的目標卻是藝術的現代化,而並不是後現代化。崛起於85時代的中國當代藝術名家們都是從模擬時代走來,用纸本通信(Fig. 1)。到了21世紀,隨著微博、微信的崛起,以傳統的台式電腦終端為依託的數碼交流方式也發生了改變。有學者認為當數碼已經滲透到社會的方方面面,不再新鮮時,也就進入了後數碼時代。[4] 中國的當代藝術家們在創作時幾乎難以避免使用數碼手段,這使得數碼藝術這一概念反而變得充滿爭議:既然所有藝術家都在一定程度上利用了數碼技術,那麼是否存在“純粹的”數碼藝術家呢?陳星漢或許能夠被稱為是數碼藝術家。

後現代主義的出現不僅打破了傳統與現代之間的線性歷史邏輯,更模糊了藝術媒介的界限。用傳統的觀點來判斷,陳星漢是一位電子遊戲製作人,不應該屬於藝術家。然而在遊戲界陳星漢的作品卻被認為是藝術,是一段美好的體驗,而不是遊戲,因為他的作品相當非主流。[5] 傳統的電子遊戲要麼強調操作,如《超級馬里奧(Super Mario)》系列(Fig. 2),要麼強調電影敘事效果,如《最終幻想(Final Fantacy)》系列 (Fig. 3);而把這兩種體驗發揮得淋漓盡致的就要數連斯皮爾伯格都贊不絕口的、由小島秀夫製作的《潛龍諜影(Metal Gear Solid)》(Fig.4) 系列了。儘管小島秀夫被認為極具編導才華,但是他的遊戲也還無法擺脫電影的影響。電子遊戲如果要為“第九藝術”正名,那麼它就必須呈現出與傳統八大藝術都不一樣的特色。而陳星漢的作品則把電子遊戲的藝術性提升到了一定高度,雖然在商業上並沒有像前面幾個系列遊戲那麼成功。

陳星漢製作的《雲》、《流》、《花》和《旅》既淡化了操作(Fig. 5-8),也沒有具體的敘事劇情,完全靠唯美的畫風面和清新的音樂給參與者帶來一種治癒般的體驗,而這種體驗儘管和傳統的八大藝術都不一樣,卻並無違和感。陳星漢所製作的遊戲歸根到底是多媒體數碼程序,具有多媒體藝術的新特徵:動態的即時性和互交性,這是傳統繪畫和雕塑所不具備的。

不僅如此,陳星漢也可以被認為是當代藝術家,因為他所製作的四部非常另類的遊戲與當代社會所呈現出來的種種問題都息息相關,甚至可以說他的洞察力更為超前。比如2005年開發的《雲》是他獨白式的作品,試圖描述他兒時因為哮喘住院,獨自在房間時的白日夢。[6] 這件作品設計了一個夢幻場景,由藍天、白雲、海島組成,參與者會在空中與雲朵互動,排除烏雲、增加白雲、淨化空氣,並且全程配有輕鬆的音樂。陳漢星的設計理念是“擴大電子遊戲呼喚情感的範圍”。[7] 他通過上海的污雲與美國更為自然健康的白雲對照,反映了現代化、工業化和城市化所帶來的尖銳問題。陳星漢所反映的問題和呈現的方式非常具有前瞻性,因為霧霾問題在中國則是到了2010年以後才日趨嚴重引發關注。[8] 他本人也十分在意強調其藝術家的身份,並向斯皮爾伯格和宮崎駿這樣的導演看齊:“我覺得自己骨子裡仍舊是一個藝術家,想要創造東西和別人分享。現在學了計算機,也只是換了個更得心應手的工具罷了。”[9]

Flow Art:

Chen’s games tended to be consistent, it was because he always applies the psychologic ideas of Flow to his work. Flow theories was coined by the Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in 1975. He postulated that when one immersed in a Flow zone, one will completely have focused on motivation; and once one’s goal was fulfilled by the motivation, the ultimate satisfaction and happiness would be achieved. Chen studied Flow theories and drafted design concepts. According to the charts, Chen attempted to find a path to happiness by keeping the balance between Challenge and Ability for overcoming Anxiety and Boredom. Through this path, participants would find happiness. It was due to such an idea, Chen’s work always appears therapeutic. Advancing from Cloud, Flow and Flower tended to be more abstract and conceptual. They formed a Taiji-flow between action and inaction, because concrete historical events (air pollution) had been downplayed. The most recent Journey can be regarded as a mature work of Flow philosophy.

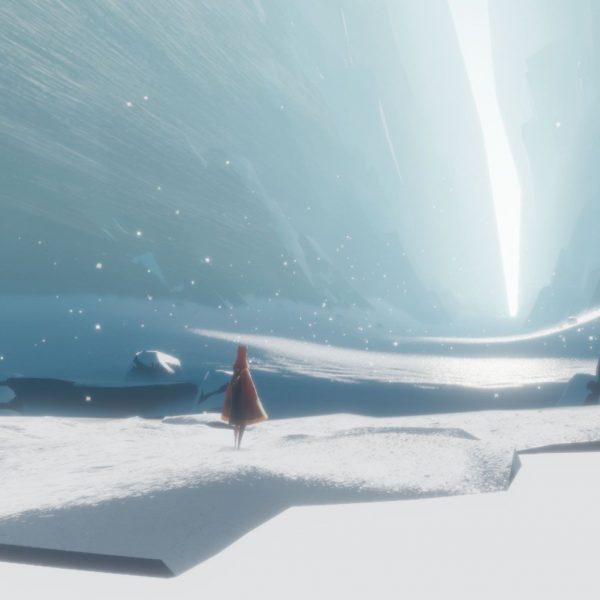

In Journey, participants would assume the role of a journeyman in abstract figure, wandering in a vast desert. In the journey, participants are required to befriend other participants. In order to continue the quest, participants ought to help each other. However, they were not allowed to communicate through texts and talks; the one viable way is to chant with music. The chant would change the surroundings of participants, and the experience is about interacting with human intelligence rather than the artificial one. Journey was a breakthrough for Chen, because the programme no longer takes participants to solely explore a virtual world, but serves as a platform for tele-communication between human beings.

Participant would experience solitude and insignificance in the vast virtual world; and only by human communication can a real emotional tie being forged. Journey transcend from being therapeutic, and was designed to help its participant to realise the crises caused by digital era: humans become indoor and lonely. And such a notion was the cultural production of the Post Digital Era, when human societies immersed into the digital world, concerns about being digital became less critical than being human. Journey expressed such a concern and reminded the people in the digital world of what is the most important experience in life journey. Through such a goal, a Zen concept could be realised: wisdom reaching the opposite shore.

從“治癒型”到“知與行”:

陳星漢製作遊戲時有一個貫穿始終的哲學理念,即“心流”理論。這一理論最早由匈牙利心理學家米哈伊·奇克森特米哈伊(Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi)於1975年提出,[10] 他認為進入“心流”狀態的人會產生一種浸沒式的投入感,讓人主動產生實現願望的動力,並且在完成願望後產生非常高的滿足感和愉悅感。陳星漢根據這套理論繪制出了作品觀念圖(Fig. 9),通過數碼程序在“挑戰”與“能力”之間尋求一種平衡,以抵抗“焦慮”與“無聊”帶來的虛無主義,進而幫助互動者找到幸福感。[11] 根據這一製作觀念,陳星漢的作品也呈現出治癒的特點。《流》與《花》相對於《雲》來說,設定更加抽象化和概念化,體現了一種“無為”與“有為”之間的太極流,具體的歷史概念(空氣污染)被進一步淡化。發行於2012年的《旅》可謂是心流藝術的大成。

《旅》讓互動者操作一名穿長袍的抽象角色,在廣袤的沙漠中向遠方山峰的頂端前行。在途中,參與者可以隨機結識另一名相同旅程的互動者;雖然兩人可以在旅途中相互幫助,卻無法通過語音或文字交流,並且無法看到對方的名字。參與者間的唯一交流途徑是沒有詞句的吟唱,這種吟唱會對遊戲世界產生影響,使參與者可以通過關卡繼續互動體驗。《旅》對於陳星漢的突破之處在於:參與者的體驗不再是人機互動,而是人與人之間的互動;程序本身只是人類遠程交際的媒介。

參與者將體驗在世界中的渺小和孤獨,繼而與陌生人結為同伴,以此使玩家真正產生興趣和其他玩家社交,建立情感紐帶。於是作品超越了“治癒”,使參與者領悟到數碼時代所帶來的交際危機:當代社會日益突出的宅文化所帶來的孤獨。這種孤獨正是後數碼時代的產物,即人類浸入數碼社區無法自拔。《旅》通過人與人之間的互動再次警醒虛擬世界的人們什麼才是人生旅途中最重要的體驗,從而達到“知與行”的禪宗式覺悟:般若波羅蜜(智慧渡過彼岸)。

Controversial digital art:

More and more art organisations start paying attention to the art possibility that may have been brought by digital programmes, however, there are many obstacles in establishing institutions, researching, collecting and presenting digital art. First and foremost, video game producers had different opinions about their identity as artists. For example, Kojima explicitly rejected the idea of treating video games as art, because he did not believe games can be collected and exhibited like paintings and sculptures. Kojima failed to realise that digital technology has already revolutionised museology: there not only exist specialist institutions; such as the Los Angeles Center for Digital Art, but also traditional art museums, such as the V&A, started establishing digital art departments. The history of digital art has been systematically stipulated, dating back as early as the 1950s. In fact, traditional art history and the idea of museum as a ritual were challenged by post modernist theories. Museums without walls, avant-garde art and curating emerged rapidly and differed from those established aesthetic systems. With the advancement of digitalising, there appeared more virtual museums, meanwhile there are more institutions collecting and exhibiting digital art. Accordingly, new methods and approaches have emerged. The music in Journey was composed by Austin Wintory. The composer deliberately created a kind of interactive sound effect, determined by the response of the participants, so that the music would tend to be unfolding in real time. Its spontaneity is similar to John Cage’s 4′33″, offering the third person the chance to reinterpret the notes. Due to such a brilliance, the sound track was nominated for the 2013 Grammy Awards for Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media, the first video game soundtrack to be nominated for that category. Since the sound track was recognised as a piece of art, the whole package, Journey, should also be regarded as such. And Jenova Chen, its maker should be worthy of the title “digital artist”. His work of Flow Philosophy not only revolutionised the way in which video games are presented, but also served as a revelation: the crisis in the Post Digital Era. Video games have become such an important part of contemporary society, only a few were praised by gamers as art, and fewer were regarded by historians as artistically significant. Jenova Chen, like those conceptualist artists, has created new forms and experiences. Even though he made a living as a programmer, nevertheless as an innovative maker (of a digital world), he is worthy of the attention in the field of art history.

數碼藝術的爭議:

許多藝術機構都關注到了數碼程序所帶來的藝術可能性,但是在構建類似美術館的收藏機構時卻遇到了不少問題。首先,遊戲製作人本身對藝術家這一身份還存在疑慮。比如,小島秀夫就明確否定電子遊戲是藝術的說法,因為他不認為遊戲像繪畫或雕塑那樣可以被博物館收藏和展示。[12] 可是近年來數碼藝術引發了博物館學的革新:不僅出現了“洛杉磯數碼藝術中心”這樣的專業展藏機構,就連維多利亞和阿爾伯特(Victoria & Albert Museum)這樣的傳統博物館也專門開設了數碼藝術部門。數碼藝術史也被系統地勾勒出來,最早被追溯至1950年代。[13] 事實上,博物館的神聖性早在上世紀末就和傳統藝術史一樣受到質疑。[14] 無牆美術館與前衛藝術和先鋒策展一樣在後現代主義的引導下不斷向傳統體系提出挑戰。隨著數碼化的深入,虛擬的博物館也陸續出現,數碼收藏也在探索中前行。由奧斯丁·溫特(Austin Wintory)里為《旅》譜寫的互動配樂和約翰·凱吉(John Cage)的不朽名篇《4’33”》有異曲同工之妙,表現了“互動即時演奏”的感覺,更受到了第55屆格萊美獎(Grammy Awards)的提名。既然作為《旅》一部分的配樂可以被認為是藝術,那麼作為整部作品製作人的陳星漢也應該被當之無愧地稱為藝術家。他的心流哲學作品不僅顛覆了傳統電子遊戲的表現形式,更用多媒體藝術的方式體現了後數碼時代所產生的危機,可謂達到了“游於藝”的境界。

[1] TR35, 2008, MIT Technology Review, <http://www2.technologyreview.com/tr35/?year=2008&_ga=1.115530630.1637195230.1457819549>, [12 Mar 2016].

[2]大狗:《陳星漢的“中國式”童年》,網易遊戲《見證》第23期2012年5月29日,<http://play.163.com/special/jianzheng_23/>, [12 Mar 2016].

[3] Mary Yakush, 1991, ROCI, Washington DC: National Gallery of Art Press, p. 161.

[4] Mel Alexenberg, 2011, The Future of Art in A Postdigital Age, The University of Chicago Press.

[5] “Top Ten Games You’ve Never Heard Of”, 2006, Game Informer, May, Vol. 165, No. 1.

[6] 《陳星漢的“中國式”童年》

[7] Ibid.

[8] 2013年12月中國中東部出現嚴重霧霾事件。中國國內的主流媒體如《新京報》、《人民日報》都有報道,並且引起了美國環保局的關注。2012年中國政府開始把PM2.5納入空氣質量監測標準。

[9] 《陳星漢的“中國式”童年》

[10] Mihaly Csiksgentmihalyi, 1975, Beyond boredom and anxiety, Jossey-Bass Publishers.

[11] Jenova Chen, 2006, Flow in Games, <http://jenovachen.com/flowingames/Flow_in_games_final.pdf>, [12 Mar 2015].

[12] Ellie Gibson, 2006, “Games aren’t art, says Kojima”, Eurogamer.net, 24 Jan, <http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/news240106kojimaart>, [12 Mar 2015].

[13] “A History of Computer Art”, Victoria and Albert Museum, <http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/a/computer-art-history>, [12 Mar 2015].

[14] Carol Duncan, 1995, “The Museum as Ritual”, Civilising Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums, Routledge.