Curated by Scott Cameron Weaver and Mathieu Paris

8 October 2015 – 9 January 2016

Mason’s Yard

Alighiero e Boetti

Mona Hatoum

Sergej Jensen

Mike Kelley

William Morris

Sterling Ruby

Rudolf Stingel

Danh Vo

Franz West

Amish quilts

Gee’s Bend quilts

White Cube is pleased to present ‘Losing the Compass’, a group exhibition curated by Scott Cameron Weaver and Mathieu Paris at Mason’s Yard. This exhibition focuses on the rich symbolism of textiles and their political, social and aesthetic significance through both art and craft practice. Beginning with the metaphorically charged conceptual work of Alighiero e Boetti, ‘Losing the Compass’ traces the poetic and subversive use of the textile medium through works by Mona Hatoum, Mike Kelley, Sergej Jensen, Sterling Ruby, Rudolf Stingel, Danh Vo and Franz West, wallpaper by 19th century English designer, craftsman and socialist William Morris and a series of quilts made collectively by the Amish and Gee’s Bend communities in USA during the late 19th and early 20th Century.

Contesting traditional notions of authorship, Alighiero e Boetti’s work points to hidden boundaries, whether aesthetic, geographic, economic or political, between the so-called ‘East’ and ‘West’. Working collaboratively with diverse groups from across the globe, and particularly with communities of Afghan women embroiderers, Boetti’s sculptures conflate notions of art and craft and individual expression with that of anonymous production. A selection of canvas embroideries mounted on board from the late 1970s and embroideries from both the 1980s and 1990s spell out phrases such as ‘Il Silenzio è D’oro’, ‘A braccia conserte’ or ‘Perdere la Bussola’, from which the exhibition takes its name, across a grid of colourful squares, combining the political, democratic and rigorous elements of Arte Povera with a dichotomy of order and disorder central to Boetti’s oeuvre.

Collaboration and political themes continue in the work of both Danh Vo and Mona Hatoum. Danh Vo’s conceptual work exposes history as it is manifested through material objects, bringing different layers of time together and interweaving personal and political narratives. For this exhibition, he has produced an installation that focuses on the often bloody history of Christian colonialism. Working with weavers in Mexico, Vo’s series of blood red rugs are dyed with cochineal, once highly prized by the Conquistadores and as economically valuable as gold, tracing how colour relates to economy, fashion and ideology. Mona Hatoum’s work 4 Rugs (made in Egypt) (1998/2015), was produced in Cairo with a local carpet school for the Cairo Biennale in 1998. Hatoum asked the school to create carpets featuring the image of an articulated skeleton, which had been dropped onto the floor to fall naturally into different figurative positions. With their brown tone and rectangular form, the rugs suggest soil graves and relate to both the massacre of 62 tourists near Luxor, Egypt in 1997 as well as to skeletons still visible in the rectangular rooms of Ancient Egyptian labourer’s houses which are sited nearby to the Luxor temple.

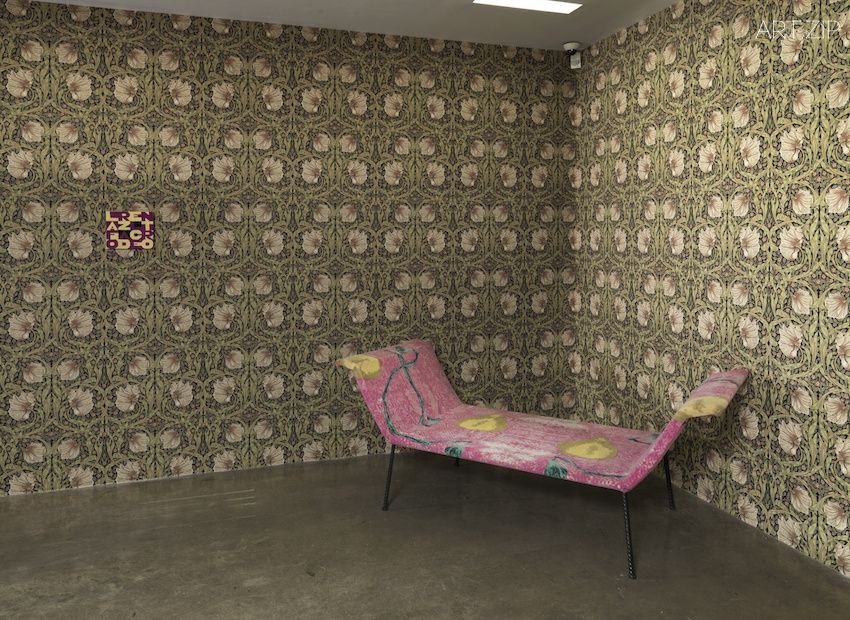

In his series of ‘Carpet’ works, Carpet #3 and Carpet #5 (both 2003), Mike Kelley uses carpet as a ground for abstract paintings that deftly allude to the domestic and quotidian world. References to the domestic continue in Rudolf Stingel’s conceptual paintings, in oil and enamel on canvas, which exactingly recreate sections of elaborate damask wallpaper motifs, mixing references to both decorative art and painting in one succinct gesture. With their all-over patterns, carved out in relief, Stingel’s de-centred compositions question the act of looking and the edge of the painting as visual limit. In Franz West’s work Nannerl(2006), steel, coco mat and carpet combine in a hybrid sculpture that incorporates textiles to suggest both a use and aesthetic value. An upholstered bench, the work sits poised between its recognition and use value as furniture and its role as sculpture, activating the traditionally passive relationship between viewer and artwork.

Sergej Jensen’s delicate and poetic work incorporates material as a symbolic interface, in minimal compositions that are sewn rather than painted. Jensen collects fabrics and textiles compulsively, such as antique scraps or bolts of expensive fabric, and commissions his mother to hand-knit pieces to his own specifications combining references to design and fashion with a history of modernist abstraction. A notion of recycling continues in Sterling Ruby’s visceral work, which mixes a punk aesthetic with gestural abstraction, incorporating and re-purposing sections of fabric or denim combined with scratched, defaced, exploded graffiti-type elements. Bleach poured onto the canvas ground creates unpredictable compositions that visibly register an action during their making.

A selection of quilts by both the Gee’s Bend community and the Amish communities display how textiles, born out of necessity, provided a creative outlet for generations of women. The intricate, vibrantly colourful geometric compositions of quilts made by African American women in Gee’s Bend, a remote, isolated area of Alabama exhibit spontaneous compositions, incorporating worn bits of clothing and textiles, while a selection of quilts produced by the Amish community in Pennsylvania display a restrained palette and strict symmetrical compositions. Both reflect how quilt-making provided an acceptable form of creative outlet.

Edited by Qiwen Ke