Royal Academy of Arts, The Sackler Wing of Galleries

5 August – 12 November 2017

This summer, the Royal Academy of Arts presents Matisse in the Studio, the first exhibition to consider how the personal collection of treasured objects of Henri Matisse (1869-1954) were both subject matter and inspiration for his work. To reveal the working processes by which these pieces were transformed in his oeuvre, around 35 objects are displayed alongside 65 of Matisse’s paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints and cut-outs.

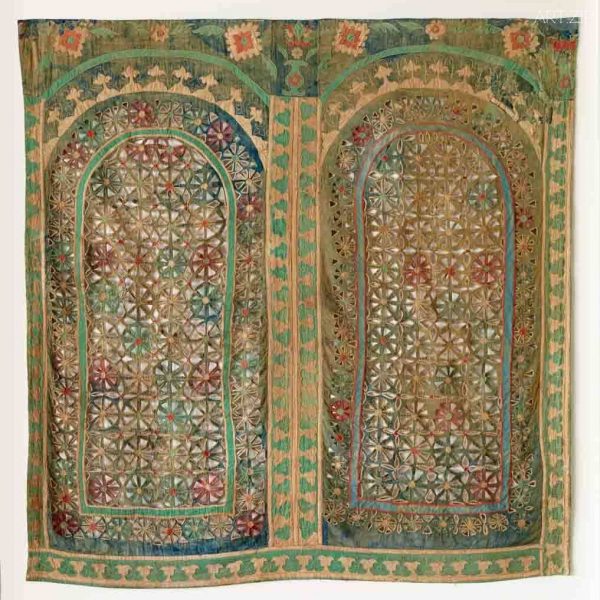

Matisse’s eclectic collection ranged from a Roman torso, African masks and Chinese porcelain to intricate North African textiles from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He selected these objects primarily for their aesthetic appeal and although not generally rare or the finest examples of the traditions to which they belonged, they were of profound significance to Matisse’s creative process. Most of the objects are on loan from the Musée Matisse, Nice, and several others are from private collections, which will be publicly exhibited outside France for the first time.

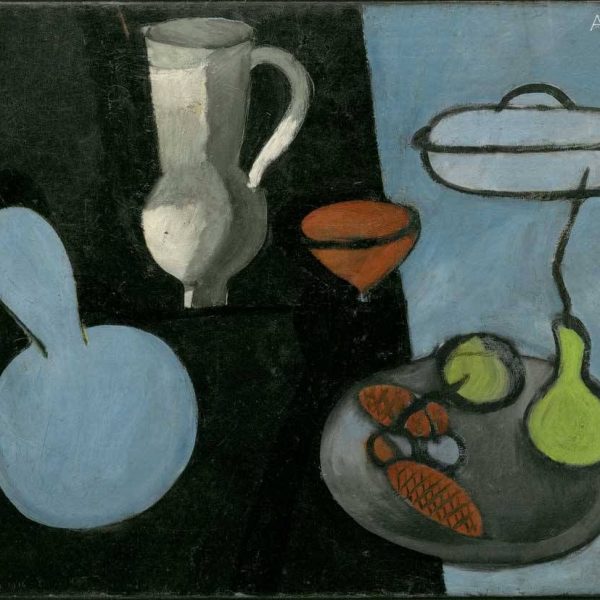

Henri Matisse, Still Life with Seashell on Black Marble, 1940 Oil on canvas, 54 x 81 cm The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow Photo © Archives H. Matisse © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2017

Matisse in the Studio is arranged around five thematic sections.

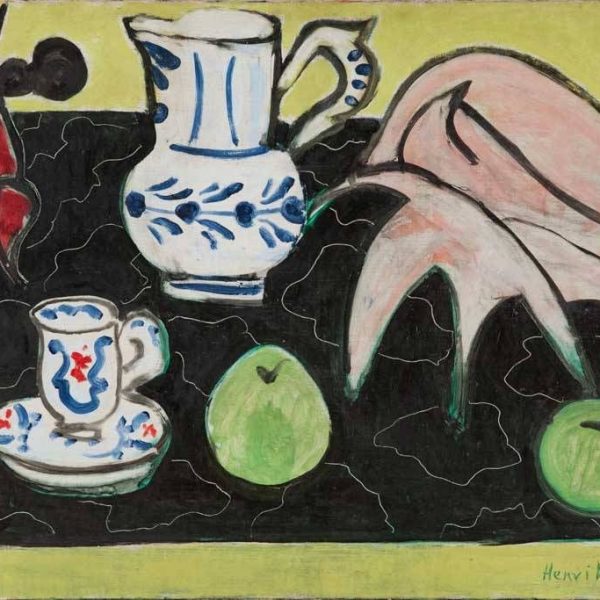

The Object as an Actor shows how Matisse reconceived elements of his collection in different works over various periods throughout his career. Matisse stated: “I have worked all my life before the same objects… The object is an actor. A good actor can have a part in ten different plays; an object can play a role in ten different pictures. The objects of his paintings and drawings were took on different ‘roles’, transforming as they interact with the space and objects around them. Matisse combined these objectors and represented them with a variety of media, colours, techniques and perspectives. A simple Pewter Jug, 1917 (Private collection), an Andalusian glass vase (Musée Matisse, Nice), and a chocolate pot given to Matisse as a wedding present (Private collection) reappear under varying guises in several works created over an extended period of time, including Safrano Roses at the Window, 1925 (Private collection) and Still Life with Shell, 1940 (Private collection).

The Nude primarily focuses on Matisse’s collection of African sculpture and the ways in which these works led him to radical innovations in portraying the human figure. Matisse challenged centuries of artistic tradition with his radical depictions of the female nude. Matisse drew on a plenty of sources: photographs from an erotic publication billed as an ethnographic journal, Classical sculpture and, above all, the Central and West African works that he collected. Particularly, Matisse’s engagemnt with African sculpture marks a turning point in modern art. A number of Matisse’s sculptures are included, such as Two Women, modelled 1907-8, cast 1908 (Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C). Works representing the nude from other cultural traditions were also important to Matisse, including Bamana figural sculptures from Mali (Private collection) and a statue of the goddess Nang Thorani from Thailand (Musée Matisse, Nice), as well as contemporary photography.

The Face explores how he conveyed the character of his sitters without resorting to physical likeness. Many of Matisse’s portraits borrow motifs and ideas from traditions emphasising the simplification of human features, particularly from the African masks that he owned. African masks made a particularly strong impact on his portraiture, both stylistically and conceptually. As he strove to convey the personal impact of his subjects, the abstract simplification and forceful geometric designs of African art helped Matisse to go beyond straightforward resemblance towards portraits. Paintings by Matisse including The Italian Woman, 1916 (The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York) and Marguerite, 1906-7 (Musée Picasso, Paris) is hung alongside objects such as an African Pende mask (Private collection), a small bronze bust of the Buddha from Thailand, and a French medieval head of a saint (both from Musée Matisse, Nice).

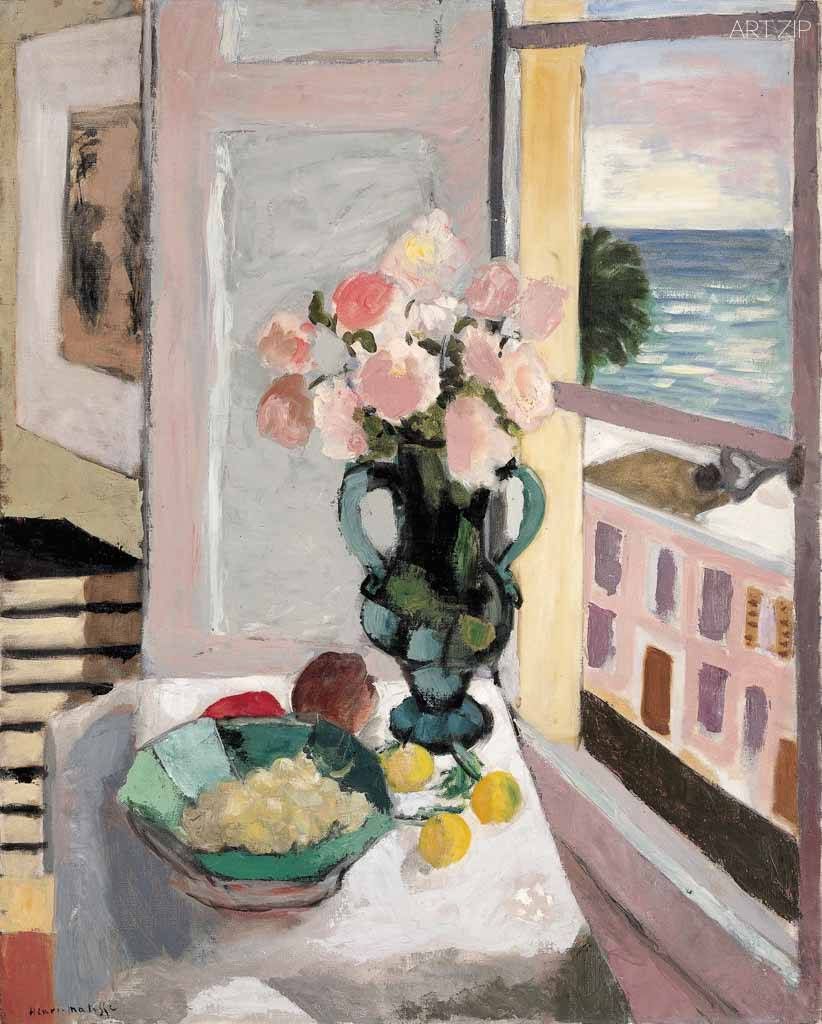

The Studio as Theatre is centre around the Nice interiors from the 1920s, in which Matisse increasingly relied on studio props from the Islamic world, such as North African furniture, wall hangings and Middle Eastern metalwork, accentuating the importance of pattern and design in his continuing search for an alternative to the western tradition of imitation. Using furniture textiles and objects from North Africa and the Middle East, he theatrically ‘dressed’ his Nice studios, creating elaborate ‘sets’ of rich visual effects to portray in his works: vivid colour contrasts, layered patterns and the illusion of expanding space. Matisse borrowed different cultural design and objects in his paintings. They were far more than props: their materials and forms invigorated his search for a more expressive alternative to Western figuration. Highlights by Matisse within this gallery include The Moorish Screen, 1921 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia).

The final section, The Language of Signs features Matisse’s late works and the inventive language of simplified signs in his cut-outs. The free and innovative works dispalyed here were mostly completed in the fourteen-year period that he referred to as his ‘second life’. The late works synthesise many of the tendencies explored in this exbition, culminating in the cut=outs, the defining achievement of Matisses’s last years. Objects from his collection, including a Chinese calligraphy panel and African kuba textiles, are exhibited alongside the artist’s cut-outs exemplified by Panel with Mask, 1947 (Designmuseum Danmark, Copenhagen), illustrating how, in his own words, “The briefest possible indication of the character of a thing. A sign.”

Matisse in the Studio is offer an intimate insight into Matisse’s studio life and artistic practice, exploring how the collage of patterns and rhythms, which he found in the world of objects, played a pivotal role in the development of his masterful vision of colour and form.

Henri Matisse, The Moorish Screen, 1921 Oil on canvas, 91 x 74 cm Philadelphia Museum of Art. Bequest of Lisa Norris Elkins, 1950 Photo © Philadelphia Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2017

《畫室中的馬蒂斯》于2017年8月5日至11月12日在皇家藝術學院進行展出。展覽以五個不同主題的展廳娓娓道來馬蒂斯的創作歷程。作為一個帶有傳奇色彩的藝術家,馬蒂斯也是當之無愧的收藏家,此次展覽中展出了部分馬蒂斯收藏的世界各地的藝術品,諸如西班牙安達盧西亞20世紀早期的花瓶、19世紀晚期至20世紀早期海地的平紋織梭與貼花棉布、以及阿爾及利亞的漆繪小桌等。這些泰國佛像、非洲地區的雕塑品與紡織品與中國清代的書法作品給予馬蒂斯豐富的創作靈感,馬蒂斯巧妙的將其融入到自己的作品中,以新的麵貌呈現。

馬蒂斯20歲時開始作畫,還在病床上養病的他或許還不知道,正是這段疾病的康復期得以成就他的職業。馬蒂斯的母親送給他一盒顏料以排解整日在病床上的空虛時光,於是他開始了大膽的繪畫創作。馬蒂斯的母親是當時的瓷器藝術家,對於顏色的運用也潛移默化的影響著馬蒂斯。後來在巴黎學習藝術時,馬蒂斯邂逅了印象派明亮鮮艷的感官刺激,於是他開始了大量的繪畫實踐。其中很多實踐體現在他對點畫法的運用於突破上。點畫法作為新印象主義的主要呈現方式,將印象派的色光原理進行了新的延展。在融合了新印象派更加支離破碎的筆觸與構圖后,他沉溺在這樣的風格中,更加追求顛覆性的色彩表達。這種創作手法也被稱為“野獸派”。

馬蒂斯格外重視通過畫作描繪內心感受,這正表達出野獸派的核心:擺脫理論束縛,擺脫細節追逐,自由自在的畫出內心感受到的事物的美。他的作品可以感受到他對於色彩平衡的追求與對於色塊持續至生命盡頭的堅執著。這種畫作中的魄力不僅使他成為行家嚴重的先鋒藝術家領袖,也讓他的作品具有掀起繪畫領域深刻變革的力量與恣意。對於雕塑作品情有獨鐘的馬蒂斯一直致力於講雕塑作品的形態感融合到畫作中,與此同時,異國文化的養料也充分的滋養著他。在馬蒂斯眼中,異國文化可以帶給他更多的創作靈感,於是他遊歷摩洛哥、旅居尼斯。

馬蒂斯的晚年很大一部分時間在輪椅上度過,這一時期誕生了大量剪紙作品。他通過隨性的剪裁與粘貼,將符號與創作融合進作品中。本次展覽業展出了很多馬蒂斯的剪紙藝術。這種介於雕塑與繪畫、抽象與具象之間的創作成為一門獨特的藝術語言,結合了馬蒂斯“極高的繪畫熱情”,“實現了憧憬與固有創作觀念的平衡”。同時他也詩意的棲居在這個世界,很多靈感也源於詩歌。他的晚年時光充滿詩意,每天晨起的第一件事就是讀詩,他將詩形容成醒來後呼吸的第一口新鮮空氣。詩是他心靈的長生藥,換個角度看,馬蒂斯也因而得以貫通不同派系的畫法與藝術形式,成為一代傳奇。

時間:2017, 8月5日至11月12日

地點:皇家藝術學院