Text by: Monica Chung

撰文:Monica Chung

Image Courtesy of: NUO Gallery

圖片提供:NUO畫廊

.

‘The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.’

“真正的發現之旅不在於新的風景,而在於新的眼睛。” [註1]

--Marcel Proust, French novelist (1871 – 1922)

——馬歇爾·普魯斯特(Marcel Proust),法國小說家(1871-1922)

.

Wang Yabin’s ethereal portrayals of vertiginous landscapes, and everything that travels through such resplendent beauty, is informed and inspired by the rich cultural heritage of a bygone China. His monochromatic paintings resemble colour reversed photographic negatives, distilled contemplative visions that could have been captured in our past, present or future. If Marcel Proust were alive today, perhaps he would be an acquaintance of Wang’s, and been inspired by his oneiric landscapes, which have borne witness to everything, yet remain untouched and transcend time.

For centuries, nature, the great muse, with its unforgiving and eternal beauty, has consistently challenged and lured artists, and Wang is very much a part of this hallowed tradition. His pastoral observation of nature, and mankind’s isolated position within its cosmology, serves as a spring from which his impressions of another place and time are called forth. In the finest examples of the European Romantic Tradition, such as Caspar David Friedrich’s ‘Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog’ with its figure, upon a rugged precipice, looking down to a burgeoning sea, we find an expression of the duality of man’s place in this world, his life both significant and insignificant. Wang Yabin’s depictions, albeit in less tumultuous natural environments, possess the same contemplative disposition, and embody the same spirit. His ‘Hailar’s Elm woods’ presents to us a cloaked figure, deep in wildwood, where familiar Chinese octagonal Ba Gua motifs are seen to float beside the long and wide vertical brush strokes, suggesting a cosmological harmony between man and his surroundings. Through such expressive forms, one begins to sense a kinship with Leon Spillaert whose brooding self portraits, look towards vast horizons and assess man’s relationship with nature.

Closer to home and where we find Wang Yabin working today, the Henan Province in the Eastern Central part of China, is steeped in more than 5,000 years of history. The birthplace of Chinese civilization, it remained at the centre of culture, politics and the economy up to 1000 years ago. Ancient ruins, relics and artifacts are still found throughout the region. To the West are a range of gentle sloping mountains, including the sacred Songshan (Song Mountain) which guards and protects ancient Buddhist temples and shrines; namely the Songyue Pagoda, the oldest example to be found in China. Zhengzhou, the province’s capital sits close to the foothills of these mountains. An hour’s travel out of the city, the roads begin to fade into the mist and disappear, and one has the sense of traveling through time…

王亞彬用輕盈的方式刻畫眩目的風景,以及在燦爛如斯的美麗中穿行而過的一切。畫的靈感來自很久以前的中國所留下的遺產。他的繪畫常以一種色彩為主,類似底片的反色效果,提煉出令人感懷的視覺,寄托屬於我們的過去,現在,或者未來。如果馬歇爾·普魯斯特在今天還活著,他也許會成為王亞彬的知交,並且被他夢般的風景所啟發。那些風景是一切的見證,超脫時間之外,孑然而立。

許多世紀以來,自然,這個偉大的女神,用幾近殘酷而永恒的美麗,引誘並挑釁著藝術家。王亞彬當然是這個神聖傳統的一員。他將整個自然視作自己的牧場,並在那裡看見了人類在宇宙中的孤獨,喚醒了自己對另一個時空的印象。在歐洲浪漫主義傳統的典範作品,比如弗雷德裏希(Caspar David Friedrich)的《霧海上的漫遊者(Wanderer above the sea of fog)》[註2]這幅畫裡,一個人站在崎嶇的山崖頂端,望著澎湃的雲海,折射出人在世界中的位置,以及不凡卻又渺小的生命。王亞彬描繪的自然環境雖然更加平和,卻有同樣的冥思氛圍和同樣的精神。他的《海拉爾的海拉爾》裡面有一個批鬥篷的人,身處森林深處。長而寬的筆觸似乎在那裡形成一種接近八卦圖形的韻律,暗示著人與周圍的一切的終極關係。這幅畫讓人想起萊昂·斯皮拉爾特(Leon Spillaert)那些沈靜的自畫像,裡面的形象望著遙遠的地平線,琢磨著人在自然中的位置。

王亞彬的家鄉和他創作的地方都在河南省,位於經歷了五千年歷史浸泡的中原東部。那裡是中華文明的發源地,直到一千年前,那裡還是中國的文化、政治和經濟中心;至今仍在出土古代遺跡、墓葬和藝術品。王亞彬家鄉的西面是延綿的山脈,包括守護著古代重要佛教寺廟的聖地嵩山。那裡有中國最早的佛塔嵩嶽寺塔[註3]。省會鄭州就在山腳以東,從那裡駕車一個小時之後,路途就漸漸隱沒在迷霧中,仿佛是前往另一個時空的旅途。

…The art of the Han Dynasty produced sculptures and objects that were employed predominately as burial artifacts and placed within tombs. Representations of the human figure and animal depictions were carved on tombstones, whilst paintings were mostly for ornamental purposes. It was at the beginning of the Tang Dynasty that multi-ethnic influences, from the ever growing influx of foreigners travelling The Silk Route, permeated Chinese society. These influences established important new art forms such as Buddhist sculpture and the ink renditions of landscapes. The Five Dynasties period to the Northern Song is today heralded as ‘The Great Age of Chinese Landscape’ from which a truly distinctive style emerged. Scholars mastered the technique of creating three dimensional space between the foreground and background of the picture plane, creating a sensuous distance between the two sections, and leading to the famous and beloved images of mountain peaks rising out of misty clouds.

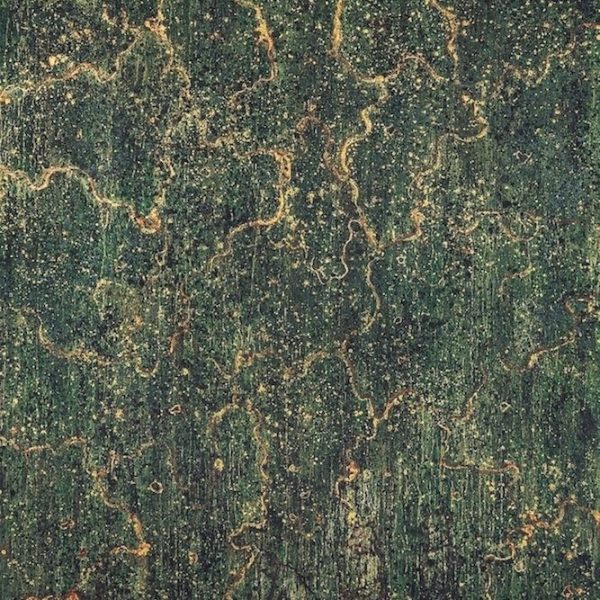

Today, Wang Yabin’s sensitive handling of the medium has furnished him with the skills to accomplish the same reverence to that which is represented in these historical ink wash paintings and Han sculpture. In the same fashion that the traditional Chinese palette employed colours such as moon white to mimic natural phenomena, Wang’s subtle monochromatic shades recall the aged patina of ancient pottery, emoting a sense of nostalgia and melancholy. His paintings suggest ‘Memento Mori’, and reinforce a deep and spiritual connection to the long and complex cultural ancestry of the land.

漢代[註4]墓葬藝術裡有大量的雕塑和小物件。墓室的畫像磚上雕刻著人物和動物圖案,而裡面的繪畫幾乎都是裝飾性的。在初唐時期[註5],外國旅行者沿著絲綢之路源源不斷地趕來,將不同民族的文化滲入中國社會。這些影響帶來了重要的藝術變革,尤其反映在佛教雕塑和水墨風景畫上。五代和北宋[註6]的繪畫誕生了真正的開創性風格,並在今天被稱為“中國風景畫的黃金時代”。那時的文人已經善於在平面上制造富有縱深感的前景和背景,並進行了更具感官性質的距離劃分,創造出著名的山峰高聳於雲霧之上的意境,深刻地影響了後世。

今天,王亞彬對油畫媒介敏感而細膩的掌控,讓他有能力賦予風景同樣的尊嚴,就像古典水墨和漢代雕塑所做的那樣。傳統的中國色彩體系更加接近自然,這從“秋香”等色彩名稱上就能窺見一二。王亞彬用同樣的精神建立起自己的色彩體系。他為單一色彩注入豐富的層次,讓人想起古代陶器那種具有時間感的色澤,喚起懷舊和憂郁的情感。他的作品讓人想起一句拉丁箴言:“人皆為將死(Memento mori)”;同時,又與屬於他的土地的、輾轉流長的文化建立起深刻的精神聯繫。

.

‘All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players…

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts…’

“世界不過舞臺而已,

男女不過演員而已……

各懷出入之道;

一人分飾數角……”

--‘As You Like It’ William Shakespeare, English poet and playwright (1564-1616)

《皆大歡喜(As You Like It)》,威廉·莎士比亞(William Shakespeare),英國詩人和劇作家(1564-1616)

.

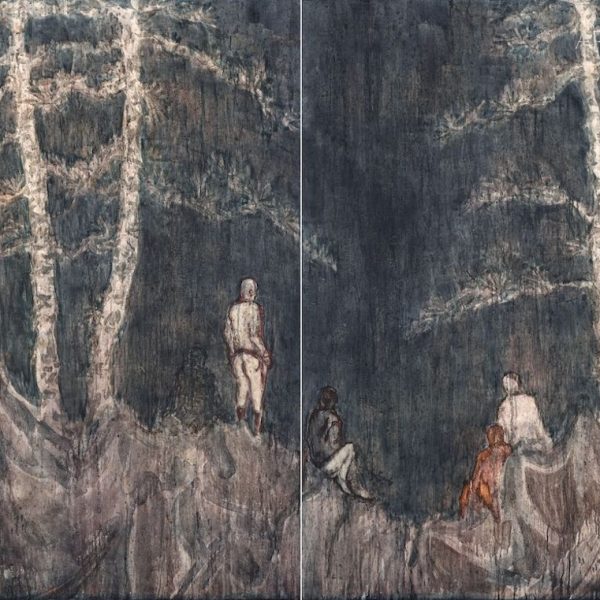

Shakespeare’s widely known and recited words, point to the ‘seven ages’ that man transitions in life, from his birth to his death. Although Wang’s immortal protagonists escape such a fate, they still play their different parts amidst the scenic backdrops of stars, pine trees and mountain peaks. Surrounding his cast of players, the artist draws straight lines that trace a loose rectangular shape, suggesting a proscenium view of the world, and the staging begins to reveal itself. Gaston Bachelard’s concept of topoanalysis – the theory that the house serves as the backdrop to the conscious being, and that memories become part of the present existence – could be said of Wang’s surreal arrangements; ‘…in the theatre of the past that is constituted by memory, the stage setting maintains the characters in their dominant roles. At times we think we know ourselves in time, when all we know is a sequence of fixations in the spaces of the being’s stability…that is what space is for’. Wang’s paintings are scenes from a hypnagogic storyboard, playing to a narrative that is populated by elements that are familiar to all.

莎士比亞這段廣為流傳的文字,指向人的生命從出生到死亡的“七個階段”。雖然王亞彬畫中那些永生的主角逃離了這一命運,卻仍然在星空、松樹、山峰組成的布景前扮演著不同的角色。他常常用直線畫出一個矩形,包圍著自己的演員,暗示這世界就是一個舞臺,並讓布景逐一顯現。在加斯頓·巴赫拉(Gaston Bachelard)的認識論裡,閉合的空間是背景,包容一切有意識的存在;而記憶則是當下的一部分。這正好可以形容王亞彬的超現實布景。“……在記憶形成的、過去的舞臺上,布景會保持角色最重要的特質。有時候,我們會認為,自己是通過時間來了解自己的,但實際上,我們想了解自己,需要’存在’的各種穩定狀態都固定在空間中,串聯起來,並成為我們所知的全部……這就是空間的意義。”[註7]王亞彬畫中的場景類似催眠所使用的故事模版,它們是由人們都很熟悉的元素所構成的。

As with early portrait photography, perhaps the fictional places that Wang depicts, connect his abstract feelings between what is real and unreal. In the painting ‘Road of Pine Shadow’ we see an aerial view of ramblers walking through a forest, on a path made of something that cannot be grasped; the shadow in the title suggests to us a sense of ‘otherness’. A geometric outline hovers above the walkers, crowns the landscape, and converts the outdoor image into an interior one – this Origami transformation draws us into Wang’s representation, where exterior and interior are both visible and artificial. The painting ‘Pavilion’ brings us to an isolated male figure, who stands within a hut surrounded by forest, and we watch him as he returns our gaze. This is a temporal space for contemplation, perhaps the one that Michel Foucault describes when he speaks of the mental and physical spaces of ‘otherness’ that exist, and how we might be in two places at once, as during a phone call conversation, or when reflected in a mirror. ‘The mirror is, after all, a utopia, since it is a placeless place. In the mirror, I see myself there where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space that opens up behind the surface; but it is also a heterotopia….it makes this place that I occupy at the moment when I look at myself in the glass at once absolutely real, connected with all the space that surrounds it, and absolutely unreal, since in order to be perceived it has to pass through this virtual point which is over there.’ If this is true, then Wang’s solitary figure suggests a portal for our own reflection.

Wang Yabin’s subliminal gateways are inspired by his own existence, in both the physical and historical realm of his native land. Are we being invited to gaze into a parallel world of representation, or are we inside the room itself looking back at our reflected selves? The artist’s ‘Little Goddess’ renders such manifold existences. The painting portrays, through an oval shaped aperture, a figure holding a small statue. Is the statue a representation of the man himself, his alter ego, or the essance of his very being? Such layered construct recalls Velasquez’s ‘Las Meninas’. Here we see the King and Queen of Spain’s image reflected in a mirror on the back wall, and although they are not formally posing for the painting, they are included in the pictorial space; this suggests a connection between illusion and reality. Wang’s tender depiction of a resting couple ‘Lover Stone’ creates just such a displacement, and consequent opening for the viewer. Against a blood red haze, amidst tall pine trees, the lovers seem to be part of the rock beneath them. The title subscribes itself to the traditional language of local folklore. How many other couples have been subsumed in such a place of beauty? Our role as spectator is not only to observe their intimacy but also to bear witness to a transformation; the lovers have become part of nature itself.

就像早期的肖像攝影,王亞彬所描繪的虛構地點,連接著他亦真亦假的抽象感覺。在《松影道》這幅畫裡,我們能俯瞰林中的漫遊者,他們的道路是由難以辨明的東西組成的。標題中的“影”字暗示著某種“他者”;幾何形的輪廓浮現在漫遊者周圍,環抱著風景,將室外的景色折回室內。這種類似折紙的轉變顯現了王亞彬的再現方式:內部與外部均是可見的,並且是人為的。《涼亭》那幅畫裡有一個孤獨的男子形象,站在樹木環繞的木亭裡,當觀眾望向他時,他也報以回望。這是一處暫時的冥思空間,也許就是福柯(Michel Foucault)所談論的,“他者”所存在的心理空間。福柯認為一個人可以同時身處兩地,比如在打電話的時候,或者照鏡子的時候。“鏡子,說到底,是一個烏托邦,因為那裡是一個無處之處。我看見自己在鏡子裡,但我不在那裡。那裡是一個不真實的虛擬空間,展開於表面之後。它也是一個異位的烏托邦(異托邦)…當我在鏡子裡看見自己所處的空間時,這個空間就變得絕對真實了,因為我看見它與周圍的空間相連接;但它又變得絕對不真實,因為想要感知這一點,我必須通過那面鏡子裡的虛擬之處來確認。”[註8]如果此言不虛,那麽王亞彬畫中那個孤獨的形象,就為我們自己的映像打開了一扇門。

畫中這扇潛意識的大門源自王亞彬自己的存在——他存在於故鄉真實的,以及歷史的緯度中。那麽,我們究竟是被邀請,去騁目於一個被再現的平行世界;還是原本就在那裡,回望著我們自己的映像?《小女神》這幅畫就呈現出這種存在的多樣性。透過一個卵形的小孔,畫家描繪了一個手捧小雕像的形象。這座雕像究竟是畫中人自己,還是他的另一個自我,抑或他核心的“存在”本身?這種多層次的結構讓人想起維拉斯奎茨(Diego Velasquez)的《宮娥(Las Meninas)》[註9]。在那幅畫裡,西班牙國王和王後的影像在背景墻上的一面鏡子裡顯現出來;雖然他們不是那幅畫的正式模特,卻出現在畫裡,暗示真實與虛幻相連。在《映心石》這幅畫裡,王亞彬用柔和的方式描繪了一對休息的情侶,展現了這種真假之間的位移感,並讓它隨之面向觀者。在血紅色的薄霧和高聳的松樹林裡,那對情侶似乎成為了身下岩石的一部分。畫的標題追隨了地方民俗;有多少對情侶曾經置身這個美麗的地方呢?作為觀眾,我們不僅在觀看他們的親密,還在見證一種轉換:情侶成為了自然的一部分。

Wang’s objectivity as an artist transmits a deep and graceful candour. His paintings pose questions to our perceptions of what is truthful, and do not provide us with simple answers. A worthy title for the painter would be that of a time traveller. He takes in all the things that surround him, and his paintings are manifestations of such journeys. These speak to us through the palette and brush strokes previous masters have entrusted to him. His immortal protagonists and memorialized landscapes capture all that is eternal, casting a pulsating nostalgic aura that penetrates us, whilst nourishing an alternative perception of our own reality through our imagination.

王亞彬用屬於一名藝術家的客觀性,傳遞著深沈和優雅的直率。他的繪畫對我們的感知提出了疑問:什麽才是真實的,卻又不提供簡單的答案。“時間旅行者”這個頭銜也許適合這位畫家。他吸收自己周圍的一切,並用繪畫展現這種旅途。他用過往的大師托付給他的色彩和筆觸,向我們訴說著。畫中那些不死的角色和被紀念的風景,捕捉著一切永恒,散發著懷舊的光環,浸入我們內心;同時又借助我們的想象,培育出對現實的另一種感知。

.

Footnote:

Date of painting: 1818Songyue Pagoda 523AD

Han Dynasty 206BC-220AD

Tang Dynasty 618 – 907AD

Five Dynasty – Northern Song Dynasty 907-979AD

Gaston Bachelard, ‘The Poetics of Space’ Beacon Press, p.8

Michel Foucault, ‘Of Other Spaces, Utopia and Heterotopia’ Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité October, 1984; p. 4 (“Des Espace Autres,” March 1967 Translated from the French by Jay Miskowiec)

Diego Velásquez, ‘Las Meninas’ 1656 註1: 本文所引用的所有原文由本文譯者翻譯,與相關中文出版物的翻譯會有出入。——譯者註

註2: 作品完成於1818年

註3: 嵩嶽寺塔,建於公元523年

註4: 漢代,公元前206年-公元220年

註5: 唐代,公元618年-907年

註6: 五代至北宋,公元907年-979年

註7: 加斯頓·巴赫拉,“The poetics of space”,Beacon Press,p.8

註8: 米歇爾·福柯, ‘Of Other Spaces, Utopia and Heterotopia’ Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité October, 1984; p.4。英文由傑·米斯考維科(Jay Miskowiec)翻譯

註9: 作品完成於1656年