Text 撰文 x by Jesc Bunyard

Translated 翻譯 x by Cai Sudong 蔡苏东

Edited 編輯 x by Michelle Yu 余小悅

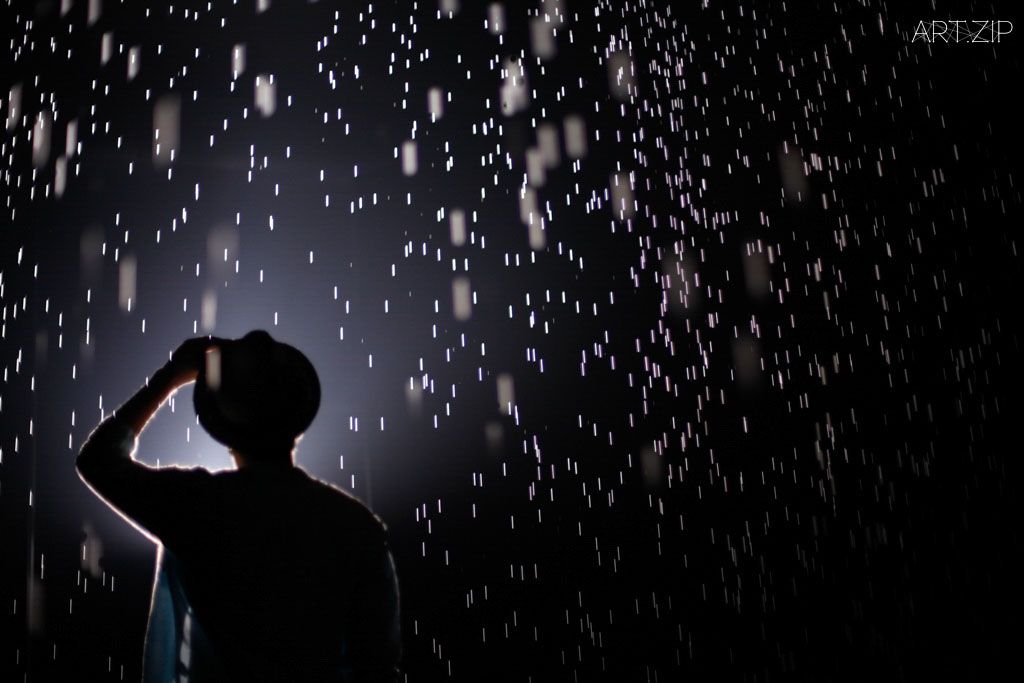

Collaborative studio rAndom International are most famous for their Rain Room installation. This work enchanted viewers first at the Barbican in London and subsequently at MoMA in New York, Yuz Museum in Shanghai and LACMA in Los Angeles. Led by duo Florian Ortkrass and Hannes Koch, the team blend science and art in their investigations of the relationship between man and machine. The viewer, or rather participant, has an emphasized role in the work. These extraordinary works are unleashed upon the world ready and yearning for human interaction.

As well as continuing to tour Rain Room, the studio are planning ever-bolder works partially informed by their recent residency at Harvard, enabled by Le Laboratoire. One of these is Study for Fifteen Points, which explores how little visual information is needed for the human brain to perceive a human form.

Visiting their main studio at The Old Warehouse in London, we discussed the success of Rain Room and how it’s approached by different audiences, and also the terms like ‘digital art’ in the contemporary landscape towards less restrictive interdisciplinary practices.

Florian Ortkrass and Hannes Koch

ART.ZIP: How did rAndom International start?

RI: We met at Brunel University in 1998, at one of their campuses west of here near Winsor, on a hill. It was a bit like a monastery. In the last year we, individually, had pieces in exhibitions. We thought: “why don’t we join forces?” That’s when we came up with the name, because we were doing all different things, plus we were very intrigued by the word random. There’s no direct translation into German, or there is a translation but it usually has a negative connotation. We went to do our Masters degree at the Royal College of Art, again working in several projects, both at the college and externally, together. We finished the RCA and we incorporated the studio in 2005.

It started out as this collective umbrella. We did our first actual Random project, where we worked together under that name, at the Valencia Biennale in 2003. We had already been working together on our respective individual projects, but there our complementary skills and interests really became something bigger and more focused.

Rain Room (2015) 150 Square Metres Exhibited at Yuz Musuem, Shanghai courtesy of Yuz Foundation and VW China Photography by Delia Keller

ART.ZIP: You’re most well known for the incredible Rain Room installation. Do you consider this your signature work? Do you still work with it or is it considered done and move on to the next work?

RI: Far from putting it to one side, it’s still very interesting and current within the practice, but it’s just one of the works. We wouldn’t have, in our wildest dreams, expected that sort of persistent public reaction to it. It is also, still to this day, not really guided by that. If anything, then we’re picky about when and how we show it, we can afford that due to the public success of it. There are other interesting bits in it that’s in development, we’ve got four more to make and we’re actively involved in every single one and they all will have permanent homes. We’re actively involved in making and finding those homes. I don’t see it as a done and dusted thing.

Each time Rain Room goes to a different country, it’s different.

ART.ZIP: Your works use installation in order to study collective behaviour. Are the reactions that the Chinese audience had different to the ones experienced elsewhere?

RI: There was a strong difference yes. If you want to go into the specific Rain Room behaviour, the high-density population behaviour in China is very different from London or New York. In New York and London it was all about the individual experience, solitude. In China, people went in large groups, of 10 or 15 people, switching off half of the Rain Room by moving collectively. I wouldn’t say it defied the purpose, but I think next time we will set it up a little differently to take that into account. There was a very different collective behaviour, how people experience the work and themselves. It was 1 or 2 people at a time in LACMA and there were 15 or 20 people at a time, moving as a chunk in China.

It’s the different definitions of personal space.

That becomes manifest in Rain Room. I think the way people use it and experience it here reflects that. Here [London] you like to be in it alone and have it for yourself. That’s not a thing in China.

Initially we were thinking of one person in the Rain Room. If we had a different cultural background, we would have thought of it differently.

We would have probably made a completely different work. I wouldn’t argue that Rain Room doesn’t work in China. I think going forward, which is interesting when thinking of new work, that experience is definitely something that will remain.

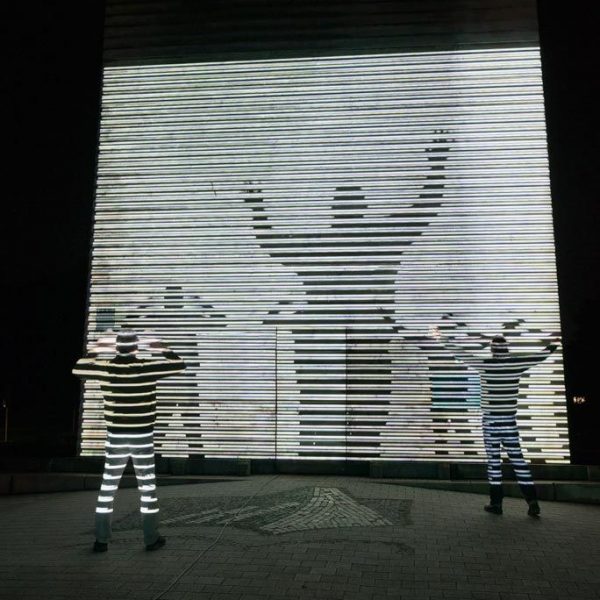

Study for Fifteen Points / I 2016 Motors, custom driver electronics, custom software, aluminium, LEDs, computer 712 x 552 x 606 mm

ART.ZIP: For your new project Study for Fifteen Points, will it exist on a larger scale? Your previous work engages more with the audience, does Study for Fifteen Points just move automatically?

RI: At the moment, yes. It’s very much what it says: A Study for Fifteen Points. There’s a much larger work, a human sized work in production, which is going to be presented publicly at Menlow Park at PACE. This study and also our research and talks programme at Harvard at Le Lab is really serious. We are studying to what extent we can open the sculptural up for engagement, to what extent behavioural reactions are interesting or boring, and to what extend we can implement the motion of the viewer and whether that’s interesting. We’re really actively studying that, looking at the technical possibilities and, foremost, the conceptual implications. We don’t always see the need for interaction. I think our interpretation of the man/machine, viewer/object, viewer/environment relationship is much broader. There’s something powerful about the recognition of human motion and there is something potentially powerful about recognising yourself, but there’s something potentially one-liner-ish about it as well. We’re gagging to make sense of it and it’s not happening. The big one is going to go along 12-metre rails, it’s not going to be a study anymore, and it will be exuberant.

You can even scramble the movement up and the brain works hard to make sense of it, and in most cases can still see, that it’s still a human. We haven’t even touched that at the moment, we have the Fifteen Points.

ART.ZIP: Digital art can be a dividing term, some people think it’s too broad or outdated, whilst others think there is no digital art, digital is merely a tool to use. Some would see it as constrictive, but it’s good to use such a decisive term to get passionate opinions. What’s your view?

RI: I think it cuts yourself short. By compartmentalising yourself, you limit yourself. I find it very unhelpful and irrelevant. Previously, if you wanted to show stuff that used digital or tech as art, you were in a limited number of spaces, like Ars Electronica. Now it’s not the same, with most people today, compartmentalising is really not a thing.

ART.ZIP: Most of the contemporary art we encounter is inter-disciplinary, with artists like yours, starting dialogues between different genres inside and outside of art. I know you’ve collaborated with dancers. What do you feel the benefits are from bringing in outside collaborators?

RI: Every time we do something it’s partially exciting because it’s new. The idea always comes first. Working with dance and Wayne McGregor for example, we didn’t really know anything about contemporary dance. It’s interesting how people use their body as a material and what is involved in that, including remembering an hour of choreography. I would have no idea how to start with that. That is really interesting, how people use the same engine to do very different things. In the work, there’s an appreciation that goes both ways.

There is appreciation and challenge. I think we make them do stuff that they would normally not do and likewise. So that creates a fairly rich ground. What touches me, is the contrast: the purity and humbleness of the body and then the restrained, but technically complex counterpart. That tension was great, especially with the way that Wayne choreographs, but also with normal people in front of the piece, as an extension to his suggestions. It is something that is really beautiful to watch. We wonder how it is that Wayne does what he does and how the dancers move like that do. I’m sure that some of that fuels this fascination for the body or movement, which ultimately come out in the Study for Fifteen Points or for what we’re showing for PACE. I’m sure that will fuel back and we will see what kinds of possibilities arise from exposing that work to choreography and what triggers that. It’s a ping-pong through different time frames or arches. Outside collaborators are really essential to the way we work.

It’s a bit like what we did in Harvard. We looked at how people work with different things, the in-depth knowledge or interest they have. It all comes back to the human body. If it’s within the field of robotics, then it’s how can robots work next to humans without the humans getting in the way and hurt. With every subject, you get a glimpse and get a different aspect of what it means to be human.

Rain Room《雨屋》是rAndom International蘭登國際最出名的裝置作品。這個作品首先在倫敦的巴比肯藝術中心Barbican展出,觀眾們為之傾倒,隨後又在紐約的現代藝術博物館(MoMA)、上海的余德耀美術館和洛杉磯藝術博物館(LACMA)展出。“蘭登國際”工作室由Florian Ortkrass和Hannes Koch兩人領銜的,他們的作品融合了科學和藝術,探討人與機器之間的關係。觀眾,或者說參與者,在他們的作品中有著舉足輕重的地位。他們這些非凡的作品,恰好誕生在這樣一種背景下,即我們的世界對於人類的互動,既具備了條件,又充滿了渴望。

除了巡回展出裝置作品《雨屋》,該團體(工作室)還在進行一個更大膽的計劃,這個計劃的創作來源於他們近期在哈佛大學的駐地項目,這個項目是由當代藝術設計中心Le Laboratoire牽頭的。當中便包括了新作品《十五點研究(Study for Fifteen Points)》,探索的是人類大腦在辨認人體型態時所需要的視覺信息最小值。

我們來到了“蘭登國際”在倫敦的工作室The Old Warehouse,和他們探討《雨屋》的成功,以及不同的觀眾是怎麽看待這件作品的。同時,我們也討論了在越來越沒有嚴格界定的當代跨學科實踐中,諸如“數字藝術”這些概念的問題。

ART.ZIP:“蘭登國際”是如何產生的?

RI:我們1998年在布魯內爾大學認識,那是靠近溫莎的一個校區,在一座小山上。那兒有點像修道院。在最後一個學年,我們各自都有作品參加展覽。我們想:“為什麽不一起合作呢?”就在那時候我們想到了“蘭登國際”這個名字,因為我們做的是不同的東西,再加上我們對“隨機”(random)這個詞非常感興趣。這個詞沒辦法直接翻譯成德文,就算可以勉強翻譯,它通常也有負面的含義。我們後來一起在皇家藝術學院(Royal College of Art)攻讀碩士學位,在幾個項目上再次合作,這包括了校內校外的項目。我們獲得了學位後在2005年正式註冊成立了工作室。

“蘭登國際”一開始就有共同體的意味。我們在2003年瓦倫西亞雙年展上的作品是第一個以“蘭登國際”為創作人名義的作品。在此之前,我們只是在各自的項目上合作,但從那時起,我們在技術和興趣上的互補才變得越來越多、越來越集中。

ART.ZIP:《雨屋》是你們最廣為人知的作品。你覺得它是你們的代表作嗎?你們還在持續跟進這個作品嗎?還是這個作品已經完成了,正在進入下一個作品的創作?

RI:要說我們已經把這個作品放在一邊了那還為時尚早,這個作品依舊是很有趣的,仍然是在不斷發展當中,它只是我們諸多作品中的一個。我們從來沒有想過公眾對這個作品有這麼持久的熱情。它的受歡迎度並沒有影響到我們。如果說真的有什麽影響的話,也只不過是因為它的成功,我們能夠有足夠的籌碼對展出的時間和方式提出要求。這個作品還有一些有趣的方面在發展中,它已經從原來的一個版本發展到四個版本,我們在每個裝置作品上都積極參與,希望它們將來都有一個能夠永久展示的空間。所以我們在積極製作的同時,也在努力為它們找一個“家”。所以我不認為《雨屋》這個作品已經徹底完成並被擱置一旁。

《雨屋》每到一個不同的國家,它都是不一樣的。

ART.ZIP:你們的作品是以裝置的形式來研究集體行為的。中國觀眾對此的反應和其他國家觀眾的反應有什麽不同嗎?

RI:是的,有非常不同的地方。如果我們看看具體的“雨屋”行為方式,中國觀眾的高密度參與和倫敦或者紐約觀眾是非常不同的。在紐約和倫敦,這是一種個體體驗,是單獨的,而在中國,人們常常是三五成群的,10至15人一組進入,他們一起活動,往往導致“雨屋”一半的空間都不“下雨”。我不會說它違背了我們原來的構想,但我們在未來創作的時候會把這個因素考慮在內。這種集體行為真的是讓我們感到意外的,觀眾對於作品和自身的體驗也是不同的。在洛杉磯藝術博物館,“雨屋”裡往往一次只有一兩個觀眾,但是在中國,一次就有15或者20名觀眾進入,成群結隊地移動。

這也反映了不同人群對於個人空間的定義有所不同。

這一點在“雨屋”裡異常突出。人們使用和體驗它的方式體現了這一點。在[倫敦]這裡,人們更喜歡單獨待在“雨屋”裡,享受個人與作品的互動。但在中國,人們似乎並沒有這種想法。

一開始,我們的設想就是“雨屋”裡每次只待一個人。如果我們不是有這樣的文化背景,我們一開始就不會這麽考慮了。

我們或許就會創作出完全不一樣的作品。我不會爭辯《雨屋》在中國是否背離作品原來的理念。但在未來我們構思新作品的時候,我們還是會保留這種強調個人體驗的理念。

ART.ZIP:你們的新作品《十五點研究》會以更大規模的形式展出嗎?你們之前的作品與觀眾的互動較為密切,這次的《十五點研究》僅僅是自動化運行的作品嗎?

RI:是的,目前是這樣。就是如字面所描述的:十五點研究。我們將會有更大型的版本在製作當中,它將與真人一般大小在Menlow Park曼羅公園的PACE佩斯畫廊公開展出。我們在哈佛大學Le Lab進行了非常嚴肅的學術研究和研討會。我們探討雕塑的可能性,雕塑在何種程度上可以與觀眾進行互動,在何種程度上的移動行為對於觀眾來說是有趣的或是無聊的,在何種程度上我們引導觀眾的參與能讓他們覺得有趣。我們探討的不只是技術上的可能性,更重要的是觀念上如何對觀者產生影響。我們並不覺得參與式的互動是必需的。我們對於人與機器之間、觀者與物體之間、觀者與環境之間的關係的看法是應該更廣闊。認識人類活動的原理也許能夠更好地認識自己,也許其中蘊含著非常重要的意義我們還不知道,但也有可能是插科打諢式的笑料。我們總是渴望了解自己,但卻總是無功而返。《十五點研究》會有一個更大型的版本,裝置會沿著12米的軌道“行走”,到時候它就不是單單的人體學習了,它會像真人一樣充滿生命力。

在未來,你甚至可以操控它的活動軌跡,然後讓它充滿各種意義,但最根本的,你還是可以看出它是模擬人體型態的。我們還沒開始把這個理念延展得更深,我們目前只有最初始的版本《十五點研究》。

ART.ZIP:“數字藝術”可以說是分歧很嚴重的稱謂,有些人認為這個詞太空泛、太過時,有些人認為根本沒有“數字藝術”這種東西,數字只是工具。還有些人認為這個詞的含義是狹隘的,但是使用這種關鍵字可以激發更多有趣的思考。你對此怎麽看?

RI:我覺得這是作繭自縛——你把自己歸入一個小領域,局限起來了。我認為這種名稱是很無益、且無關緊要的。在以前,如果你想把涉及數字或科技的東西作為藝術品展示出來,你能利用的空間本來就屈指可數,比如Ars Electronica (奧地利的文化教育科學研究院,專門從事新媒體藝術研究,建於1979年)。現在就不一樣了,對於現今大多數人來說,這種歸類毫無意義。

ART.ZIP:我們所見到的大多數現代藝術都是跨學科的,就像你們一樣,在藝術領域內外建立各類跨學科的對話。你們也曾經和舞蹈演員合作過,這種跨界合作帶來了什麽好處?

RI:每次我們開啟新的項目,最令我們興奮不已的,有部分原因是由於某種新穎性。想法永遠是最重要的。和舞蹈家合作,比如Wayne McGregor,一開始時我們並不了解現代舞。舞者怎樣使用他們的身體作為媒介/原材料,以及這其中涉及到的方方面面,比如熟記一小時的編舞等等,這都讓我們充滿興趣。換作是我,我完全不知道該怎麽開始。這便是有趣的地方,人們怎麽從相同的理念出發,最後完成不一樣的創作。在這次合作中,我們都對對方有了更好的了解並學會了互相欣賞。

另外,欣賞和挑戰是一並存在的。我想,我們肯定會讓他們做一些他們平時不會做的事情——他們也一樣。這樣我們就能共同探討更為廣闊的領域。讓我覺得觸動最大的是一些強烈的反差對比:人體活動的純粹性和謙卑性,機器運行的限制性和複雜性,都是一種“技術上”的抗衡。這種張力是巨大的,特別是Wayne韋恩的編舞,以及在作品前觀看的普通人——這些在觀看的人也成為了作品的一部分,凸顯了這種動態對比。這種動靜的結合真是迷人的一幕。我們不知道韋恩Wayne是如何做到的,也不知道其他舞者怎麽能如此舞動。我想這個合作激發了我們對於人體及其活動的迷思,融入了我們的《十五點研究》以及我們將在PACE畫廊展出的作品當中。我想未來也可能會通過編舞的方式來發展《十五點研究》,來看看到底有怎樣的可能性。這樣的跨界合作超越了時間和學科的限制,所以對我們來說這樣的合作項目意義非凡。

這有點像我們在哈佛的項目。我們研究人們是怎樣進行各式工作的,以及他們有著怎樣的知識或興趣。這些歸根結底還是關於人的研究。如果這算是機器人學的領域,那我們研究的應該是機器人怎樣和人類共處,如何自由使用又不會受到傷害。在每個課題裡,我們都能管中窺豹,從另一個角度認識何為人性。

Blur Mirror (2016) By Random International Glass, custom electronics, motors, aluminium frame, cameras, computer, custom software 2360mm H x 1140mm W x 115mm D Photography by Damian Griffiths, courtesy Pace London

Find out more: