Strangers(1*): Daido Moriyama and Hiroshi Sugimoto

“Each instant covers the entire world.” Dogen: Shobogen

“每個瞬間都包含了整個宇宙的無限。” ——道元禪師《正眼法藏》

Hiroshi Sugimoto. Photo credit_ Sugimoto Studio.

It is not often that two major exhibitions of two artists of the same media, of the same nationality and approximate maturity occur in the same city at the same time with such contrasting outcomes. Indeed, what might be striking within this difference is the sense that comes with it that each of the artists appear to have not only occupied a different relationship to their respective technologies of photography but also much more tellingly been living in such a different feeling related to being in possession of occupying a space in the world. It is this presentation of respective life worlds that marks this difference with such a marked effect.

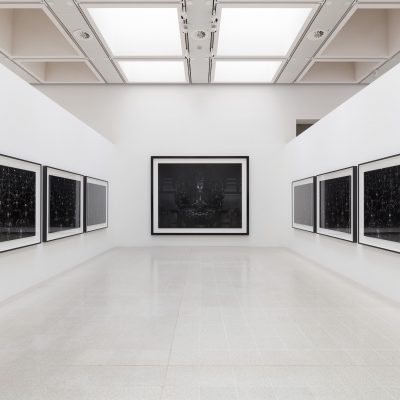

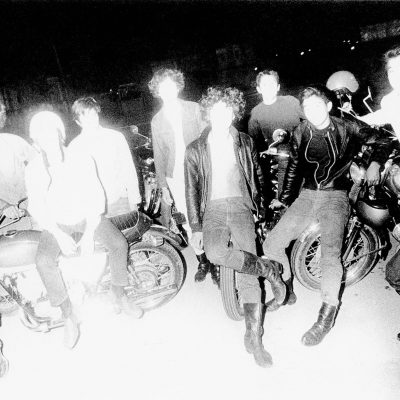

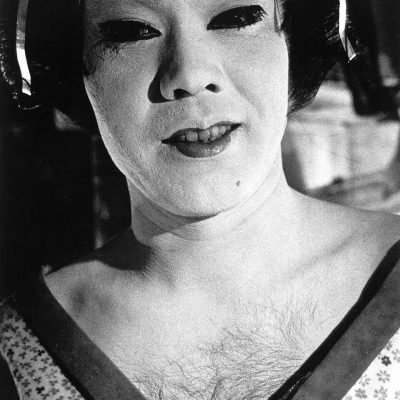

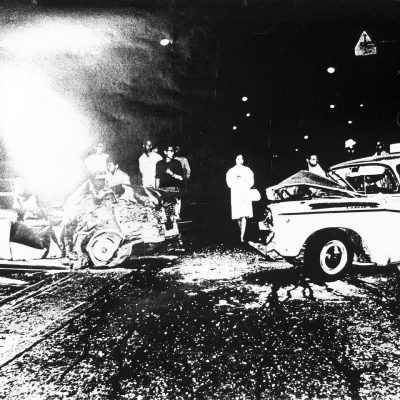

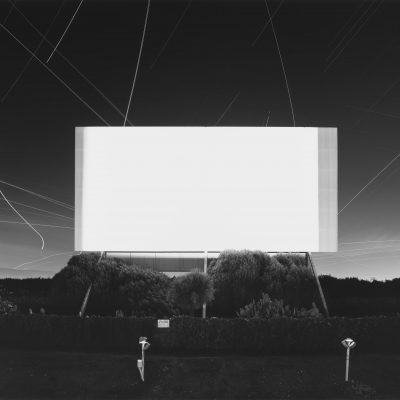

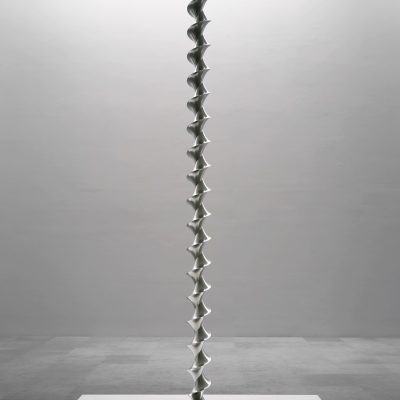

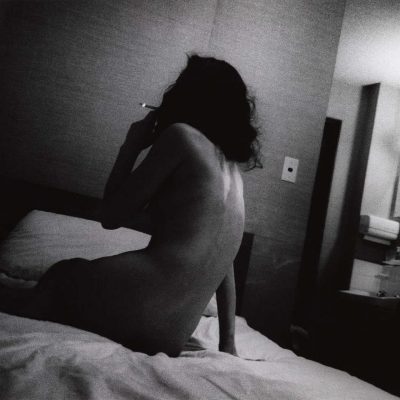

Whereas the presentation of Moriyama work in the cramped space of the Photographers Gallery is an experiment in how to extend the possibilities of making visible the restlessness of a practice that was constantly on the move, the only experiment in the Sugimoto exhibition at the Hayward Gallery is in how it might be possible to achieve perfection of presentation. Moriyama work is one the surface a continual exploration of the errancy of the medium or how far it might veer towards errancy to achieve a special affective encounter with the subject in question or view as opposed to the pristine technological perfection that defines the appearance of Sugimoto’s work. Moriyama is risk, Sugimoto is perfection, and even more tellingly, not only the contrast of risk and perfection, but something closer to that of dirt and cleansing within the gestural economies of these respective works. If Moriyama’s subject matter is the disorder and chaos of the street, then Sugimoto delivers us into a universe where seemingly no subjects are present. This difference might even be chilling in its implication because it is born out of an ontological articulation born out of occupying the space of late modernity. It might be expected from this difference that the work of Sugimoto in aligning itself with technological perfectibility would be aligned with a utopian aur but instead it might be read as chilling on the level of its affective encounter in that it represents a world without the human subject or at least a post-human vision in that the human is its leftover trances, its pre-history, its vestiges or its haunted after life. Moriyama is so close at times to the human subject that he might be partly blinded by its proximity, so we are given over to fades, blurring, striations, fragmentary vulnerabilities, out of focus residues within the process of depiction, in short, a world seemingly breathless and out of place. Against this Sugimoto is a world born of exact calculations and distances, the otherness of immeasurability existing as the elsewhere of these limits, aesthetic immobility and frozen solitude, suspensions, re-occurrences, schemas, meditations on being and time, and haunted after worlds.

Of course, it should be possible just to claim that such aesthetic contrasts are all part of the condition of late modernity and so should be passed over as incidental. They are but a passing through and over of this condition after all. Better then to occasion such an event of co-extensity as a sign of vitality, or even the culmination of a process of declaring a rich and potent constellation within Japanese photography alive to its own special mode of manifesting difference. This would amount to accepting casual determinations within unfolding histories but if this contrast is simply understood as the vagaries of an art world struggling for its own peculiar mode of arresting attention, then it might amount to missing a paradigmatic shift within the aesthetic landscape. Art can both show reality, but at the same time remind that art itself has a double character, for it is an object that signifies itself as being present or congruent in the world, but also serves as a speculation of other possible worlds. In its double character there needs to be a resistance to the existence of the world as simply that which is given over to representation of it as being all that is the case. This implies that the artwork does not have a stable identity or of possessing a desire to reveal truths, which in the words of Adorno “does not fit into this world.”(2*)

We might imagine with the Sugimoto exhibition that nothing can supersede it, such is its technical perfection, like an aesthetic utopia, harmonious and complete. There is within this an image, invisible perhaps, of the artist’s struggle to create his or hers own cosmic ordering, a world of clarity and bliss, that signals a departure from the noise of the world. In this it comes close to the world of pure mathematics with all its engagement with pristine logic. Not quite what Adorno evoked with his idea of art being the offer of a “utopian blink” but an offer, nonetheless. An archive then to remind of the broken dreams of the Enlightenment, of the distant poetic refrains of Classical Far Eastern poetry, or meditations related to philosophical aporia. Such things are embedded within the very apparatus of depiction as a savouring of the afterlife or residual traces of the work.

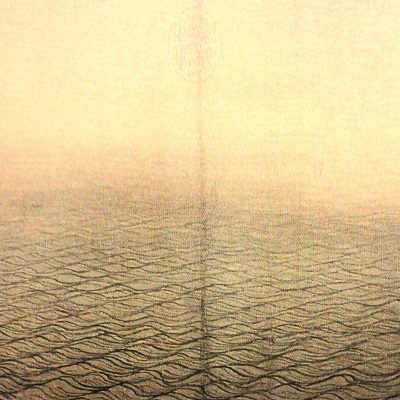

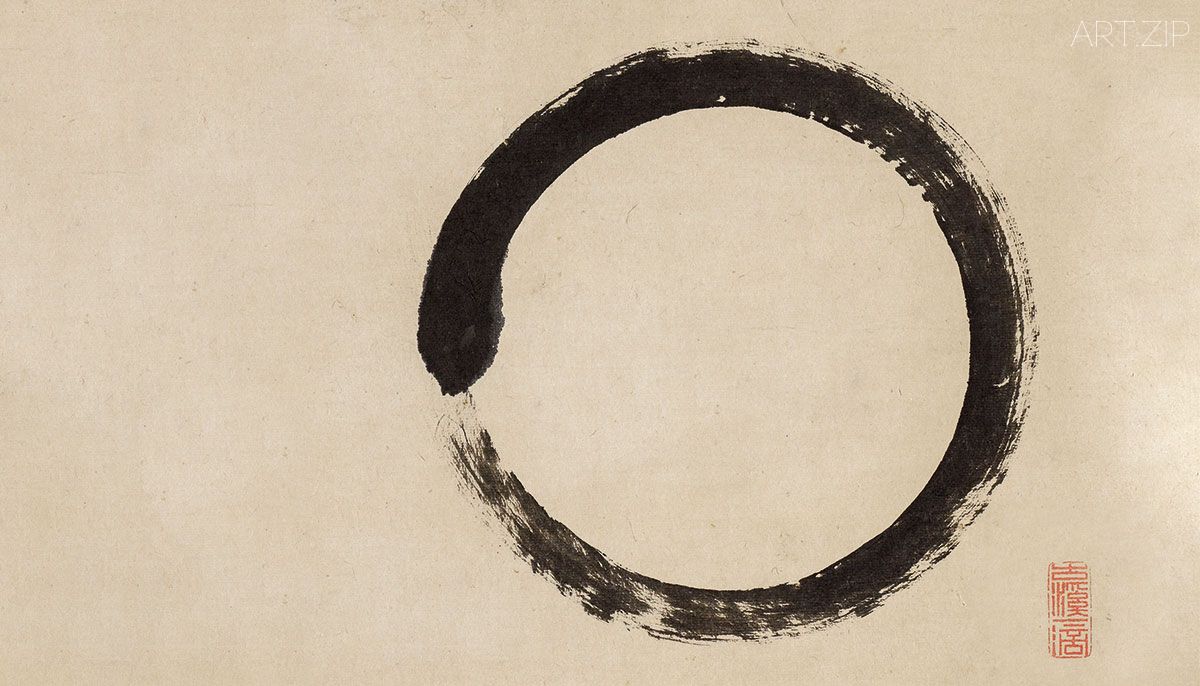

Enso by Taido Shufu, 19th century, Japan, courtesy of Minnesota Institue of Art

A Zen Enso ink drawing is invariably imperfect, yet it gestures a state that is nondual. In this way it raises itself to be its own reality in which mind and nature are continuous. It speaks through a feeling of poverty, just enough paper, just enough ink. It has little by way of appeal other than to minds willing to follow its course. Left alone to ponder such matters it is possible to bring to the fore questions related to the relationship between the artist’s power to schematise, then to construct an apparatus for the process of doing and then the institution of art in showing. The question that might be culled from this within the contemporary context pertains to the idea that the institution apparatus becomes the guiding force in directing the presentation in question. Partly the institutional imperative here is to occupy the present as a form of conquest and this implicates the diminishing of tradition and the taming of the speculative drive both of which are openings to the vulnerability of or within the present. The future of the work is in the withdrawal of its presence, not in its assertion. The vulnerability of the works in question is what the institutional apparatus wishes to overcome with its rhetoric about confidence (this is mainly what economics power is constructed out of). How often is the phrase, “this is a confident show”, as opposed to a term, such as “this an exhibition which displays its own vulnerability”? In this light it is ironic that Sugimoto stated in a discussion that a price of success has been provided with too much money to have to dispense with, demonstrating with this a faculty to reverse perspective on things deemed to be significant on the outside.

Memory and Time

“…the image is not a matter of beauty. Rather, it is a matter of a certain tension in the look. An image draws the look, draws it in. This tension of the image is time. In time, I come before what is coming; I come right up to a thing that comes up to itself. I come, in other words, right up to the coming of the thing. What we call an “artist’s work” is nothing other than the organisation of this experience.”

Jean-Luc Nancy, Multiple Arts (P215)

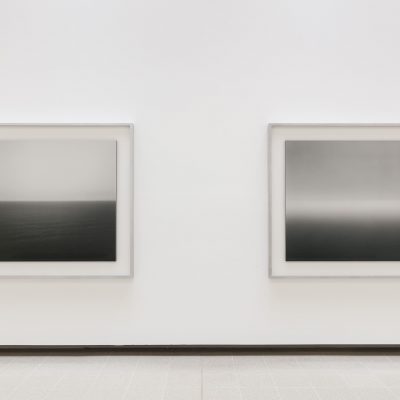

Under normal circumstance an account of artworks comes first, but in this instance, there is the idea that despite the polemic, there is still a singularity of art that supersedes contextual matters. Both artists deal in some way or other with the question of memory and the way this question finds circulation within the contrasting presentations. There are two works that appear to be at the forefront of this process of recollection and these are anyone of any number of seascapes by Sugimoto and the photograph of the dog by Moriyama. These two examples are furthermore amongst the great works of the entire contemporary period and will surely endure beyond this time frame by becoming ciphers for the continuation of the working of the aesthetic memory body. Both these two examples have been continually reworked on the level of their respective scale and in turn context. The question here is do they remain the same works despite this elasticity, or do they re-emerge as a constant feature of their process of becoming? Surely it is a constituent feature of the artwork to display this order of speculative content as they become submissions to the critical process which starts to be integrated into the process of becoming. This is why works either become part of the redundancy of time passing within the period which gave rise to them or expand beyond this initial push and pull of tarrying within time frames.

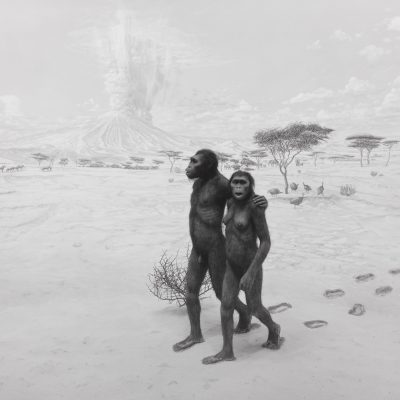

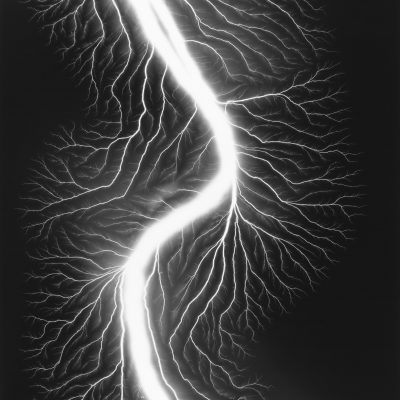

In Sugimoto’s Ocean series, we appear to stare into the space in ways that give rise to radical doubt. On one level the sea might object like, or as though frozen in time.(3*) An ocean is both a substance but is also a pattern, and in looking at an ocean, the sense of a constant pattern of re-occurrence gives rise to the feeling of its own self-sufficiency and its sense of being there. This sense of eternal re-occurrence gives rise to the sensation of being dwarfed by it and overwhelmed by its temporal and everlasting presence. As a spectacle, its gaze traps within our own fragile relationship to time. In this series Sugimoto works on our ready-at-hand relationship to both time and representation through a series of almost imperceptible shifts, the most notable being through the length of exposure creating both a sense of stilling, but also emptying. It is as if the image has eradicated the traces of time and thus life itself. We might wonder if this is either pre-time or even after-time such is the disjunction to our own immediate sense of presence. They remind us of a possibility that the world might exist as a medium without the human subject and in doing so they sever our relationship with representation. What we are left with is a sense of impermanence, which rearticulates our relationship between being and time. The series brings to the fore two quite distinct aesthetic conjunctions, that of the mathematical sublime(4*) and the Far Eastern relationship to spiritual and aesthetic emptiness(5*). Inscribed into the fabric of these works, is the play of both spatial paradigms. There are a series of album paintings in the National Museum in Beijing by the Southern Song artist Ma Yuan which are simply studies of water of a vast inland lake and these works prefigure Sugimoto by almost a thousand years. There is a Zen maxim that everything derives from emptiness and then withdraws back into it, and it is this which gives rise to the notion of the void being the basis of being. Sugimoto might be seen to open out the difference with the Western Modernist meditation upon nothingness, particularly in the writing of Martin Heidegger’s ‘Being and Time’. The series itself appears to offer each possibility without becoming a quasi-treatise on the difference between the emptiness and nothingness. Put in another way such traces are part of the fabric of the work even whilst retaining autonomy from these traces. This is why there is a doubled over fold of memory within and without the work on the reality of the difference between infinity and immeasurability. This difference might come to the fore either philosophically or aesthetically, but it is why within a Far Eastern context there was a tradition of the artist monk and coupled with this a notion of an aesthetic transmission beyond the scriptures. Anyway, this detour might throw light on how his art might be understood or related to investigating the medium of photography as “an ancient level of human memory”. It is as though Sugimoto is attempting to explore this zone of perception, both in the context of a before life, but also an after-life. Photography as a medium glides into these spaces in which a perception of radiance and shadow are captured, as opposed to solidity and presence. Photography here exists in the elsewhere of the world, in zones of fading, in densely layered shadow, in afterthoughts, in spheres of remembrance, and in that haunted place in which beings are both departing and stirring to enter yet again. This serves to remind us that we do not look long enough at things, that in our flight from the anxiety engendered by transience. We glance this way, and then that way to avoid that look that might enter things to pass through and over.

Daido Moriyama, Stray Dog, Misawa, 1971. © Daido Moriyama

In a photograph from 1971 ‘A Stray Dog,’ Daido Moriyama had discovered a symbol both for himself but also of Japanese society. With this discovery there is also a passage into why, out of all the thousands of photographs, one should function as a symbol or emblem within a practice focussed upon constellations of images. Bertolt Brecht talked of his work as possessing a rat’s eye view of history and it is as if Moriyama had discovered a dog’s eye viewpoint. A stray dog is an outsider to the social flux, looking back at it as if to reflect a sense of estrangement that binds it, so the dog’s viewpoint highlights this reality. This photograph served as a starting point for his book ‘Memories of a Dog’ in which he writes in compelling ways about time and memory(6*) . Many of his photographs recorded life in Shinjuku which he viewed as a place of “searing pain that goes straight to the heart.” In the process of photography there is the sense that images might come and go, become foreground, links to other images or are simply subject to fading or rendered forgotten. Moriyama adds to his meditations on time and memory when he writes: “In short, the apparent reality that I, that the photographer shoots, thinking, “Now,” is actually the intersection between the world’s boundless past that disappears into the distance, and the future that comes walking out of the distance bringing premonition and nostalgia. In other words, memory is not simply the repeated reproduction of the past. With the watershed of the continually forged “present” as the borderline, memory imagines the past, is reconstructed by passing through the variety of media, and is further projected onto the future that is to come in an eternal cycle. That’s what I think at present, as I snap pictures via my own memories. I think the documentary character of photography is not simply the freezing of the time of an event, but rather has the quality of being unceasingly involved with the totality of time stretching endlessly before and after. The fact that many people can individually share ownership of a single photograph is because their individual memories are involved in its interpretation.”(7*)

The work of memory (8*) has no exact location within the brain and is subject to continual reconfiguration and disfiguring, which explains why in part memory always includes oblivion. The artist’s work is enduring this conjunction in the search for significance. The way that light falls upon a thing, a single gesture, a trace of something can all serve as the basis of a chain of the work of photography becoming other to itself by touching what is exterior to it as an event. It is this that opens out a future yet to come. Both the two images serve to remind us of pre-human time and non-human time and as they look back, they sense strangers within the fold of time called the future. It is a relationship to the future that renders us as small within the present. The task of the artwork is not in the leap towards this future but to occasion a lingering preparation for its occurrence within the stilling or arrest of space.

We await(9*) , but smaller and stranger.

陌生人(1*):森山大道與杉本博司

兩位使用同一媒介、同一國籍且藝術成就相當的藝術家在同一城市同時舉辦兩場重要展覽並產生如此截然不同的結果,這種情況並不常見。令人印象深刻的是,這種差異不僅體現在兩位藝術家對攝影技術的不同運用上,更深層地反映了他們在感知和體驗世界空間時所呈現出獨特的個性。正是兩位對各自生活世界的獨特展現,讓他們之間的差異變得生動而鮮明。

在倫敦攝影師畫廊的狹窄空間中,森山大道的展覽是一次探索性實驗,旨在展現一個不斷變化、充滿不安定感的創作過程;相較之下,杉本博司在倫敦海沃德畫廊的展出,則是對如何將作品展示提升至完美境界的深入探討。森山的作品在表面上是對媒介偏離傳統的持續探索,他探討了這種偏離在多大程度上能夠與特定主題或觀點產生獨特的情感交流。這種做法與杉本作品追求的純粹技術完美形成了鮮明的對比。森山的作品反映出冒險的精神,而杉本的作品則是完美的化身。更引人深思的是,這不僅是冒險與完美的簡單對立,它們在各自作品的表達手法中,更像是污垢與純淨之間的微妙關係。如果森山聚焦的是街道的混亂和無序,那麼杉本則將我們引入一個看似沒有主體存在的宇宙。這種差異帶來的深層含義可能會讓人不寒而慄與不安,因為它誕生於藝術家對晚期現代性社會中的本體論的闡釋。從這種差異來看,我們原本可能期待杉本的作品因其對技術完美的追求而散發出某種烏托邦般的光芒。然而,實際上從情感角度來解讀,這些作品可能更引發一種深刻的不安感,因為它們呈現了一個似乎人類主體已消失的世界,或者至少是一種後人類的景象,當中只剩下他們的遺跡、前史的烙印,或是死後幽魂般的存在。森山有時對人類主題的描繪如此貼近,以至於他似乎被這種近距離所遮蔽。在他的作品中,我們看到的是顏色的褪去、形象的模糊不清、線條的重疊、碎片化的脆弱,以及失焦的殘影,共同營造出一個彷彿無法呼吸、格格不入的世界。與此相反,杉本的世界建立在精確的計算和測量之上,這個世界超越了測量的極限,體現為美學的靜止、冰封的孤獨感、懸而未決的停頓、主題或元素的反覆出現、嚴謹的結構與形式,以及對存在和時間的深思,鬼魂縈繞的往生世界。

當然,我們可以將這些審美上的差異視作晚期現代性的一部分,認為它們不過是偶然事件。它們不過是在這種社會條件下的一種過渡性現象而已。但更好的理解可能是,將這種現象看作是活力的象徵,或者是日本攝影界內部呈現出其獨特差異方式的一個高潮。這意味著我們接受歷史進程中的偶然性,但如果我們僅將這種差異看作是藝術界為了吸引注意而進行的掙扎,那麼我們可能就忽略了美學領域正在發生的重大轉變。藝術不僅能展現現實,同時也提醒我們它本身具有雙重特性:一方面,藝術是存在於世界中、表達自身的對象;另一方面,它也是對其他可能世界的思考和猜想。這種雙重本質促使我們必須反思,抵制僅僅將世界視為表面現象的簡化思維。這意味著藝術作品並非擁有固定不變的身份,也不總是試圖揭示真理,正如阿多諾所描述的那樣,「它們可能並不完全適用於這個世界的規則」。(2*)

在杉本的展覽中,我們仿佛置身於一種技術完美至極的美學烏托邦,和諧而完整。在這種完美之中,似乎隱約透露出藝術家在創造一個清晰而幸福的宇宙秩序而努力,彷彿是他從這個喧囂世界中抽離的標誌。它接近於純粹數學的世界,充滿了原始邏輯的純淨。雖然這並不完全是阿多諾所說的藝術提供的「烏托邦一瞥」,但它無疑是一種獨特的呈現。它如同一份歷史檔案,喚起我們對啓蒙時代破碎夢想的反思、遠東古典詩歌的遙遠回音,以及與哲學困境的沈思,這些都深藏在其藝術表現的核心之中,宛如對作品後世或殘留痕跡的回味。

禪宗的「圓相」水墨畫總是帶著一種原始的不完美,但恰恰在其中展現了超越二元對立的深刻境界。這種方式顯現出了自身的實相,其中心靈與自然緊密相連,形成了連續統一的存在。它以一種樸素的感覺訴說,使用的只是剛好足夠的紙和墨。這種水墨畫的魅力不在於外在的華麗,而在於吸引那些願意深入理解其內涵的人。當我們獨自深思這些問題時,可能首先會考慮到以下幾個方面的關係:藝術家簡化概念的能力、如何構建一個用於創作的儀器,以及藝術作品最終在哪個藝術機構展出。那麼在當代語境下,這引出了一個問題:藝術機構是否成為了指導和決定藝術展示方式的主導力量。在這種情況下,藝術機構的部分核心任務似乎是一種征服的形式佔據當下,這既暗示了傳統逐漸被淡化,也反映了對創新驅動力的抑制。這兩種現象都揭示了當代環境中的脆弱性,或者也反映了一種對這種脆弱性的接納和探索。藝術作品的未來趨勢不在於直接宣揚自己的存在,而在於從直白表達中撤回,轉而採用更為微妙、內省的呈現方式。藝術機構往往傾向於用自信和堅定的言辭來回應或遮掩藝術作品中的脆弱性或不確定性,而經濟因素很大程度上影響著藝術機構的策略和表現方式。我們會經常聽到人們說「這是一場自信的展覽」還是「這是一場展示其脆弱性的展覽」?從這種背景下來看,杉本曾在討論中諷刺地指出,成功的代價是不得不處理大量的資金,這說明了他有能力挑戰那些外界認為重要的事。

記憶與時間

「圖像並不單純是關於美的。更關鍵的是,它是一種特定的視覺張力。圖像吸引著我們,牽引著我們的目光,引領我們深入其中。這種張力,就是時間的體現。隨著時間的流轉,我們接近那些正逐漸顯現的事物,彷彿直面它們的來臨。換句話說,我們正在迎接事物的到來。所謂的『藝術家的作品』,無非是這種體驗的組織和呈現。」

—— 讓-呂克·南希,《多重藝術》第215頁

一般情況下,對藝術作品的描述往往是首要的,但在這個例子中,儘管有不少爭議,藝術的獨特性仍然超越了具體情境。森山大道和杉本博司兩位藝術家都以不同的方式探討了記憶這一主題,並將其融入他們風格迥異的作品中。特別突出的兩個作品分別是杉本的海景系列和森山的狗的照片,它們不僅在當代藝術中佔據重要地位,而且似乎會超越時代的局限,成為審美記憶持續發展的關鍵。這兩個作品在展示規模和語境中不斷演變。這裡的關鍵問題是,儘管存在這種多變性,這些作品是否依然保留了它們原有的本質,還是作為他們創作過程中的一個恆定元素而以全新的方式呈現出來?顯然,藝術作品所展示的這種深思熟慮的內容是其核心本質的一部分,因為它們不僅融入了創作的過程,也成為了批判和反思的重要環節。這就是為什麼有些作品會隨著時間流逝而變得陳舊,而另一些則能超越時間的限制,持續演進和拓展。

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Bay of Sagami, Atami, 1997. © Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist.

在杉本博司的海洋系列中,我們似乎凝視著某種空間,引發了深刻的懷疑。在某種程度上,海洋好像是被時間凝固了一般(3*) 。海洋既是實體物質又是圖案,當我們觀看海洋時,不斷重複的圖案感讓人感受到海洋的自足和存在感。這種永恆重現的感覺讓我們感覺自己渺小,被它那永恆的的存在所淹沒。作為一種奇觀,海洋的這種凝視將我們與時間的脆弱關係困在其中。在這個系列中,杉本通過幾乎察覺不到的細微變化來探討我們與時間和表現的關係,其中,最顯著的變化是通過曝光時間的長度創造出一種靜止又空洞的效果。仿佛圖像消除了時間的痕跡,從而亦消除了生命本身。我們可能會想,這是在時間之前還是時間之後,因為這與我們自己的即時存在感有所脫節。它提醒我們,世界可能以一種沒有人類主體的媒介存在,並因此切斷了我們與表現的關係。我們所剩下的是一種無常感,這重新定義了我們與存在和時間的關係。這個系列突顯了兩種截然不同的美學結合,即數學上的崇高(4*) 和遠東對精神和美學虛無(5*) 的關係。這些作品融合了兩種空間範式的遊戲。在北京國家博物館有一系列南宋畫家馬遠的圖卷作品,這些畫卷僅僅是對廣闊內陸湖泊水面的研究,而這些作品幾乎比杉本早了一千年。禪宗有一句格言,一切皆源於虛無,然後又回歸虛無,正是這一概念引發了虛無作為存在基礎的思考。杉本的作品可能被视为对西方现代主义对于虚无的冥想的一种展开和深化,尤其是与马丁·海德格尔在《存在与时间》中所表达的思想相比较。這個系列本身似乎提供了每種可能性,而不成為關於空虛與虛無之間差異的准論文。換句話說,這些痕跡即使保持獨立性,也是作品結構的一部分。這就是為什麼在作品內外有一種記憶的雙重折疊,在無限與不可測量的現實差異上。這種差異可能在哲學上或美學上顯現,但這就是為什麼在遠東背景下存在僧侶藝術家的傳統,與此相伴的是一種超越經文的美學傳播觀念。無論如何,這種迂迴可能會對理解他的藝術或將其與探索攝影作為「人類記憶的古老層面」聯繫起來的方式提供一些啓示。就好像杉本試圖探索這個感知區域,無論是在生命之前還是在生命之後的背景下。攝影作為一種媒介,巧妙地滲透進那些空間,捕捉到光與影的交織感受,而非物質的實體和明顯的存在。在這裡,攝影存在於世界的其他地方,在逐漸消逝的區域,在密集的陰影層中,在事後的思考中,在記憶的領域中,以及在那個生命既在離去又在準備再次進入的鬼魅空間。這提醒我們,我們沒有足夠長時間地觀察事物,我們逃避了由短暫性引發的焦慮。我們這樣看,那樣看,以避免那種可能穿透並超越事物的凝視。

在1971年的一張照片《流浪狗》中,森山大道發現了一個既代表他自己也代表日本社會的象徵。這一發現使我們得以解釋,為什麼在無數照片中,會有那麼一張獨特的照片,能夠成為一個重要的象徵,或在一系列相互聯繫的圖像中佔據標誌性的地位。貝托爾特·布萊希特曾談論他的作品擁有一種「鼠視角」的歷史觀,而森山大道似乎發現了一種「狗視角」的視點。流浪狗是社會變遷中的局外人,它回頭望去,彷彿反映出一種將其束縛的疏離感,因此狗的視角突出了這一現實。這張照片成為他的書《犬的記憶》的起點,在書中,他以引人入勝的方式寫了關於時間和記憶的內容(6*) 。他的許多照片記錄了新宿的生活,他將新宿視為一個「直擊心扉的劇痛之地」。在攝影的過程中,似乎圖像可能出現又消失,成為前景,與其他圖像相連,或者簡單地被遺忘或淡出。森山大道在他對時間和記憶的沉思中增添了他的見解,他寫道:「簡而言之,我,即攝影師在想著『現在』時拍攝的表面現實,實際上是消逝於遠方的無限過去和帶著預感與懷舊走出遠方未來的交匯點。換句話說,記憶不僅僅是對過去的重復再現。記憶在不斷形成的『現在』的分界線上,對過去進行想象,在通過多種媒介的過濾重構後,再投射到即將到來的未來,形成一個永恆的循環。這是我目前在通過自己的記憶拍照時所持的看法。我認為攝影的紀實特質不僅僅是對事件時間的凍結,而是與無休止前後延展的時間整體不斷地聯繫在一起。許多人能夠共同擁有一張照片,是因為他們個人的記憶參與了對這張照片的解讀。」(7*)

記憶的工作(8*) 在大腦中沒有確切固定的位置,並且不斷地被重塑和扭曲,這也部分解釋了為什麼記憶總是伴隨著遺忘。藝術家在探尋意義的過程中正忍受著這種聯結。光線落在物體上的方式、一個輕微的動作、一絲痕跡,都可以成為攝影作品鏈的基礎,這些作品通過觸及外在事件來實現自我轉化。這正是開啟尚未到來的未來的關鍵。這兩幅圖像讓我們回想起人類出現之前的時代和與人類無關的時間。當它們回顧過去時,感受著被稱為未來的時間皺摺中的陌生。正是這種與未來的關聯,讓我們在現實中顯得如此渺小。藝術作品的任務不在於跳躍到這個未來,而在於創造一種場域或氛圍,讓人在當前的靜止或暫停中深思,為理解和接受即將到來的未來做好準備。

我們在等待(9*) ,但更渺小,更陌生。

1*. “The Stranger comes from elsewhere and is always somewhere other than where we are, not belonging to our horizon and not inscribing himself upon any representable horizon whatsoever, so that his “place” would be invisible – on condition that we hear in this expression, following a terminology we have sometimes used: what turns away from everything visible and everything invisible.” Maurice Blanchot, The Infinite Conversation, P52 毛里斯·布朗肖,《無限的對話》,第52頁:「陌生人來自別處,總在我們所不在之處,他既不屬於我們的視域,也不在任何可呈現的地平線上留下痕跡,因此他的『所在』是不可見的——這裡我們要按照我們有時使用的術語來理解這一個概念:他遠離了一切可見與不可見之物。」

2*. Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory P.93 特奧多爾·阿多諾,《美學理論》,第93頁

3*. Sugimoto stated that: “Photography is a system of saving memories. It’s a time machine, in a way, to preserve the memory, to preserve time.” Also, he links photography to a “fossilization of time” which is in turn connects to time lapse techniques.杉本博司談攝影:「攝影是一種保存記憶的系統。它在某種意義上是一種時間機器,用以保存記憶,保存時間。」 他還將攝影與「時間的化石化」聯繫起來,這反過來又與時間流逝技術相連接。

4*. In his Third Critique, ‘The Critique of Judgement’ (1790) Kant makes a distinction within the category of the sublime between the mathematic and the dynamical ich is the difference between extent and force. The Third Critique was born out of a perception of a gap between the realm of necessity (nature) and the realm of freedom (morality). Kant deduced that aesthetical judgement preceded cognition and thus established a notion of being beyond or before representation.康德在其《判斷力批判》(1970)的第三批判中區分了數學崇高和動力崇高,這是範圍和力量之間的區別。《第三批判》源於對必然性領域(自然)與自由領域(道德)之間差距的感知。康德推斷美學判斷先於認知,從而建立了超越或在表徵之前的存在觀念。

5*.There is a famous Sutra that simply states: “Things are not as they appear, nor are they otherwise.” `this is often coupled with a citation of the Buddha: “Emptiness does not do anything whatever to anything, nor does it not do anything.” In an Ancient Greek context these would be viewed as aporias.有一部著名的佛經簡言:「事物既非如其表象,亦非其他所是。」這經常與佛陀的話相呼應:「空無本無作用於任何事物,亦非不作用。」放在古希臘的語境下,這些觀點被視為無解的難題。

6*. “A human being is nothing more than a life spent attentively passing through an assemblage of countless scenes. You can say life is transitory and live it at that, but when I wonder where on earth a certain scene from a certain time and a certain period disappeared to, for me that is not sentimentality but rather a feeling closer to irritation. All people lose their scenes one after another. Another way of expressing this is to call it an exasperation with time. Time is not something that comes pressing down on each of us. Recalling scenes that are being lost is, simultaneously, presaging scenes of the death that is to come.” Memories of a Dog, (P156)《犬的記憶》(第156頁):「一個人的一生,不過是留心穿越無數場景的連綿時光。你或許會說生活無常並接受這一點,但當我想尋找某個特定時刻、某個特定時期的某個場景消逝到何方時,我感受到的不是懷舊,而是近似於懊惱的情緒。每個人都逐一失去他們的場景。換種說法,這就是對時間的憤懣。時間並非壓迫在我們每個人身上的東西。回想那些正在消逝的場景,實際上,也是在預示著即將到來的死亡之景。」

7*. Ibid, P.169 同上,第169頁

8*. Memory is like an organism and everything has a memory: rocks, plants, stars, oceans.記憶就像一個有機體,一切都擁有記憶:岩石、植物、星星、海洋。

9*.“Waiting begins when there is nothing more to wait for, not even the end of waiting. Waiting is unaware of and destroys that which awaits. Waiting awaits nothing.” Maurice Blanchot, Awaiting Oblivion, University of Nebraska Press, 1997 「等待始於沒有更多可等待的東西,甚至沒有等待的終結。等待不知道,也摧毀了等待的東西。等待不等任何事。」 –莫里斯·布蘭肖,《等待遺忘》,內布拉斯加大學出版社,1997年。

Hiroshi Sugimoto @ Haywards Gallery, Until 7 January 2024

Daido Moriyama @ The Photographers’ Gallery, Until 11 February 2024

Text by 撰文 x Jonathan Miles

Translated and Edited by 翻譯及編輯 x Michelle Yu 余小悅