Jonathan Miles is an artist, writer, curator, and educator based in London. He currently teaches at the Royal College of Art. His practice spans painting, fiction, and critical theory, often seeking dialogue between image and text to challenge fixed narratives and structures of meaning.

Jonathan Miles is the kind of person you remember quietly. He doesn’t rush to speak or seek attention, yet his presence carries a steady, resonant force—like a beam of light entering from deep within time. He is an artist, yes, but also a teacher, a writer, and perhaps most importantly, a listener. To many, he has been a quiet compass — not only in art, but in life.

His students speak of him with a kind of reverence that words can hardly capture. He doesn’t just teach in classrooms; he walks with them through museums and galleries, encouraging them to stand still in front of a painting, to look longer, to feel more. For him, art is not a matter of theory alone—it must be seen, touched, and lived.

Jonathan teaches not through instruction, but by presence. He stays with a question rather than rushing to answer it. He might pause in front of a painting and gently posed some questions. He believes that not all learning needs conclusion; sometimes, it’s the fermentation of a question that truly shapes us.

In his world, theory is not dry—it is tactile, like running your fingers across layered paint. His approach makes thinking feel alive, embodied. He never insists on becoming an “artist” as a title, but rather, living with imagination, allowing creativity to merge with life itself.

Jonathan’s understanding of art does not come from any one system, but from a way of being—close to experience, close to the soul. He speaks of the immeasurable, of abstraction as something filled—with scent, with memory, with silence—not empty, but thick with the stories that remain unspoken.

In this conversation, he reflects on childhood and escape, the value of fiction and memory, the slippery substance of time. He offers no fixed answers, but gently opens the door to art’s oldest questions: What is art? Why do we create? And where does that unseen trembling begin?

With him, theory becomes touchable, thinking carries warmth, and imagination remains what it has always been: a way of being alive.

喬納森·邁爾斯(Jonathan Miles)是一位生活與工作於倫敦的藝術家、作家、策展人與藝術教育者,現任教於英國皇家藝術學院(Royal College of Art)。他的創作跨越繪畫、虛構寫作與批評理論,作品常在圖像與文字之間尋找對話,挑戰既定敘事與意義結構。

Jonathan Miles 是那種你會靜靜記住的人。他不急於說話,也不試圖占據空間,但他的在場,總帶著一種低頻卻深刻的能量——像時間深處的一道光,緩慢地照進來。他是一位藝術家,也是一位教師;是一位書寫者,也是一位傾聽者。對許多人來說,他甚至是人生導師般的存在。

他的學生談起他時,語氣中常有難以言表的感激與敬重。他不只在課堂上講課,更經常帶著學生走進博物館與畫廊,親自去看、去感受那些沉默卻有回音的作品。對他而言,藝術不該只停留在語言裡,它必須被看見、被觸碰,被體驗。

他教學的方式從來不是灌輸,也不是解釋,而是一種陪伴式的同行。他願意與學生一起困惑,也願意一起沉默。他會在畫作前停留很久,不急著說話,只是偶爾發問。他相信,不是所有的學習都要有結論,有時候更重要的是讓問題在體內發酵,讓觀看本身變成一種內在運動。

在他的課堂裡,理論不是冷冰冰的語言,而是與繪畫、感受、記憶纏繞在一起的東西。他總能找到一種方式,讓學生感受到思想的柔軟——像手掌輕輕劃過顏料的表面,能感受到下層的紋理與思緒。他從不強調「成為藝術家」這件事,而是更關心一個人如何活在想像力裡,如何讓創作與生命真正相連。

他對藝術的理解,不來自某種體系,而是一種貼近生活、貼近靈魂的方式。他談論「無法衡量的事物」,談論抽象如何載著氣味與色彩,如何不再是空空如也,而是滿載未曾言說的故事與存在的縫隙。

在這次訪談中,他回望童年的凝視與逃逸,談論藝術中那「無法測量」的價值,分享他如何在虛構與記憶中開拓空間,以流動、開放的狀態回應生命的多重可能,也道出了他對當代藝術世界與藝術教育的深刻觀察。這不是關於答案的訪談,而是一場關於如何「成為另一種存在」(being otherwise)的探問。

這是一場緩慢而深邃的對話。Jonathan Miles並未提供確定的答案,卻讓我們更靠近藝術最初的提問藝術是什麼?我們為什麼創作?而那無形的震動,來自何處?

在他的語言中,理論像顏料一般可觸,思辨帶著溫度,而想像力,始終是一種活著的力量。

AZ: We know each other because of the L’art education project, at that time, you are a teacher to us. Then we know you write fictions, art essays, you do paintings, sculptures, as well. We don’t really have a chance to discuss about your background. You have a lot of experiences and interesting stories. So what makes you YOU? Is there a way to conclude every stage of your journey? When to start? And what reasons to start?

JM: When I started to go to school, I tended to spend my time looking out the window viewing birds. This contrasted with the blackboard which seemed remote and as such boring. I liked climbing trees and getting lost, so by the time I reached the age of ten I still could read books. The only thing that I appeared to be engaged in was football and drawing. From that point I learnt just enough to get by at school, but I really had no interest other than going to art school and was accepted at the Slade straight from school which was like a great escape. I remember seeing the exhibition at the ICA: ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ which made me feel that painting was obsolete, so I started to create installations and performances. Then I gave that up and started to make political posters. So, it was a mixture of starting and stopping things that was propelled by not knowing very much really. Either you talk too much or talk too little because of the lack of measure. The question becomes, how to discover this sense of measure.

AZ: 我們因為 L’art 教育項目認識,那時候您是我們的講課老師。後來我們才知道,您其實不僅寫小說、寫評論,還畫畫、做雕塑……但我們一直沒有機會真正聊聊您的背景。您有非常豐富的經歷,也有很多動人的故事。您覺得,是什麼成就了今天的您?有沒有一種方式,可以概括您一路走來的每個階段?一切是從什麼時候開始的,又是因為什麼出發的呢?

JM: 小時候上學時,我總愛看著窗外的鳥出神。相比之下,黑板顯得既遙遠又無趣。我喜歡爬樹,也喜歡迷路,直到十歲左右,我才真正開始讀書。那時,我唯一真正投入的事情就是踢球和畫畫。後來我在學校只學了些勉強應付的知識,其實並不感興趣,唯一明確的目標就是:去念藝術學校。我從中學直接考上了斯萊德美術學院,對我來說,那就像是一場逃離現實的冒險。

我還記得在 ICA 看過一個展覽《當態度成為形式》,那次讓我突然覺得繪畫好像已經過時了。於是我開始嘗試做裝置和行為表演,但不久又放下了,轉而做起政治海報。我的創作之路一直是這樣,開始一些事,又放下另一些。很多時候,其實是因為我並沒有真的知道自己在做什麼。一個人會因為缺乏「分寸感」,而變得要麼話太多,要麼沈默得過頭。我覺得人生真正的課題,是學會怎麼找到那種內在的尺度和平衡。

AZ: In your opinion, what is the power of art? What have you been insisted and what you have given up or abandoned?

JM: Talking of measure, the point of art is not to find measure, but open out the immeasurable. This is why art is quite a rare and obscure exposure but mostly it is locked into measurability which renders it prone to repetition.

AZ: 那麽您覺得,藝術的力量是什麼?這一路上,有哪些東西是您一直堅持的?又有哪些是您曾經擁有,後來選擇放下的?

JM: 說到「分寸」,我覺得藝術本身並不是為了找到一個精確的尺度,而是為了打開一個無法被衡量的空間。正因為如此,藝術顯得稀有而微妙,甚至有點難以言說。可遺憾的是,大多數時候它被關進了一個可以度量、可以評估的體系里,久而久之,就變成了一種容易被重復的東西。

AZ: How would you introduce your art practice at the moment? Is there always a theme that you are exploring? Such as time? Have you finished the 1000 paintings? How does the PRISON idea come up?

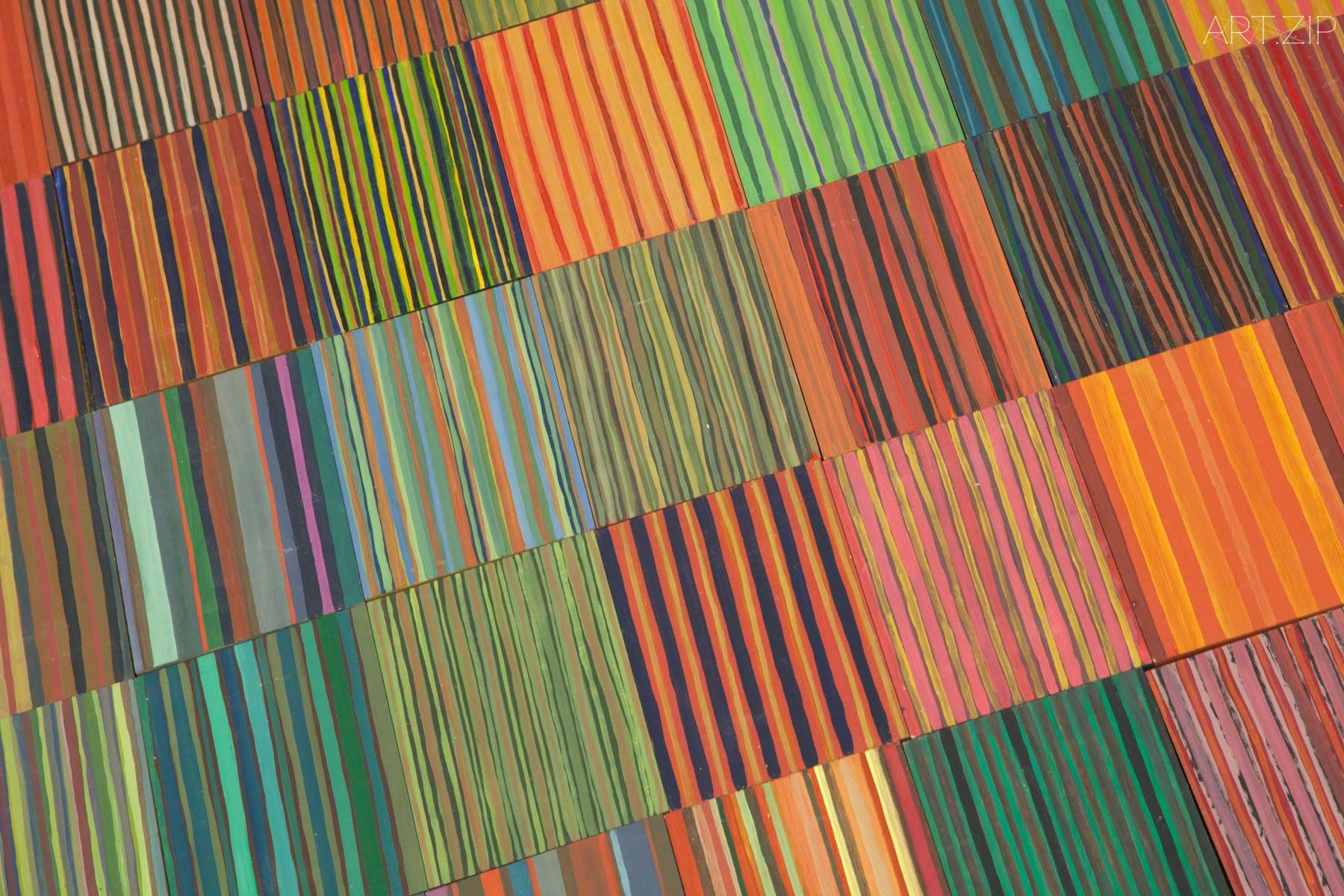

JM: My art practice is the attempt to discover the relationship to counting and the discovery of fictional spaces for this act of counting. I started to paint again with the idea of painting all the paintings I had never painted, which is an act of make believe or fiction. So, I found that I was creating grids and piles of painting rather than singular works. There was always some imaginary other doing all of this. Doors were opening and closing all the time. One moment I was in a prison like space, painting and counting the passing of days, the next finding the artist Lily O and presenting her newly discovered archive of constructions and fragmentary texts. I was thinking a lot about memory and the way that it like shifting sand. On the one side it appears to be the substance of what we are but then it is prone to be completely unreliable and so we repeat things to persuade ourselves that consistency is a possibility.

AZ: 那您現在是如何看待自己的藝術實踐的?有沒有一個持續探索的主題,比如「時間」?您之前提到的一千幅畫,現在完成了嗎?「監獄」這個概念是怎麼來的?

JM: 我一直在嘗試通過創作去理解「數數」這件事與想象之間的關係,也就是說:我們如何在虛構的空間里進行計算。後來我開始重新畫畫,起初的想法是把那些「我曾經沒畫出來的畫」一一畫完。聽起來像遊戲,其實更像是一種虛構的動作,也是一種假裝。

慢慢地,我發現自己畫的不是一幅幅獨立的作品,而是一堆堆、一組組的畫——成了網格、堆疊,而不是單一的東西。好像在這些動作背後,總有一個「想象中的他」在替我完成這些作品。那種感覺就像門一直在開開關關,一會兒我被困在像監獄一樣的房間里靠畫畫來數日子;下一刻,我又變成了藝術家 Lily O 的「發現者」,展出她那神秘的裝置作品和碎片化的文本。

那段時間我常常在想「記憶」這件事。它就像流沙,一方面它構成了我們是誰,另一方面它又那麼不可靠。我們會重復某些事情其實只是為了說服自己:世界是可以保持一致、可以被理解的。但說到底,我們只是渴望一種連續性。

AZ: Do you think your art practice is similar to Buddhist’s spiritual practice or cultivation? Has your family background influence your art practice in some way? What you haven’t tried but want to?

JM: I have always been attracted to the idea of a silent transmission, like a painting which is given to a monk as an acknowledgement of achieving enlightenment. In a way that places art at a threshold of gesture, rather than being an object that signifies something.

AZ: 您覺得您的藝術實踐跟佛教的修行有相似之處嗎?家庭背景有沒有對您的創作產生什麼影響?有沒有什麼是您還沒嘗試過,但一直想做的?

JM: 我一直對「無聲的傳遞」很感興趣。比如,一幅畫被交給一個修行者,象徵他已經頓悟——這個過程不靠語言,也沒有解釋,只是一種靜靜的傳達。我覺得藝術就在那樣的邊界上,不是為了說明什麼,而是一種姿態,一種動作的開啓。藝術,不一定非要變成一個「代表意義」的對象,它可以停留在「手勢」的起點,那一瞬間,就已經足夠了。

AZ: Are there fears in your life? What is it?

JM: I once asked my Yoga teacher what was the final purpose of yoga and he said it was to be able to meditate on the actual process of dying. I think that I might fear having nobody tell me such things. To have heard and to have seen, is everything. I remember when I was at the Slade, I would meet what I started to call ‘shiny people’ and I thought that life might be full of them, but as years past I realised that they were rare. The first thing that I look for within any student, is the degree to which they might be in possession of this quality.

AZ: 您會害怕什麼嗎?或者說,您的生命中有過什麼真正的恐懼?

JM: 我曾經問過我的瑜伽老師:「練習的終極目的到底是什麼?」他說,是為了能夠安靜地冥想死亡的過程。當時這句話讓我非常觸動。我想我真正的恐懼可能是再也沒有人能對我說出這樣的事。有人願意告訴你這些、讓你聽見、讓你看見——這就是一切。

我記得在斯萊德的時候曾經遇見一些我稱為「發光的人」。那時我天真地以為,人生會不斷遇到這樣的人。但隨著時間過去,我慢慢發現,他們其實極其稀少。現在當我面對一位學生,我最先尋找的,往往就是他或她身上是否藏著這種光。

AZ: It seems you are very interested in asian culture, can I say ancient Chinese art, what is so special of it? Does it have an influence in your life or art practice, or thinking?

Is there a particular culture that has the most profound influence in you?

JM: I had an early fascination with Classical Chinese painting particularly those of the Song Dynasty. I have no idea were or how this arose. When I would project some of these works, I would find myself taking off my shoes in order to discuss the relationship of landscape painting to the act of walking. Often this cause laughter, but I feel that it might have been a solemn gesture that indicated the feet as organs of perception, as opposed to the brain and the eye.

AZ: 您似乎對亞洲文化很感興趣,特別是中國古代藝術。這部分對您的創作或思維有什麼影響嗎?有沒有某一種文化,對您的人生產生了特別深遠的影響?

JM: 我很早就對中國古典山水畫著迷,尤其是宋代的作品。說實話,我不太確定這是從哪裡來的,也許只是某種直覺。當我在課堂上投影這些畫作時,我常常會脫下鞋子,然後談論「行走」和「山水畫」之間的關係。雖然這常常引來笑聲,但對我來說,那其實是一種莊嚴的動作。我始終覺得,腳也可以是感知的器官,不一定非得是大腦和眼睛才算。走路、感受、觀看——這些東西其實是連在一起的。

AZ: As above, there are many roles you are playing, what is the relationship between these?

JM: I feel that I just do things that come to me, so if an artist asks me to write for them, then it is an opportunity for something to occur. I have little sense that this is part of constructing a creative identity. If things keep on coming, then it is the possibility of being able to realise different stages of becoming otherwise, then what you might have been. I remember meeting a Vietnamese healer who said he wanted to teach me, but my life went in another direction, but I wonder what would have arisen if I had elected to exercise this possibility. Nothing is fixed, so the point is to remain fluid. I have many outlets, so I am never bored, but at the same time I have no single form of ambition or focus. It is more a matter of living close to imagination and its expansion as opposed to cultivating different types of activity. Imagination is anarchist whereas of life might incline towards more conservative ways of being.

AZ: 您身上有很多身份:藝術家、作家、老師、策展人……您怎麼看這些角色之間的關係?

JM: 我從來不是為了「建立身份」而去做這些事。通常是某個契機來了,比如有位藝術家請我為他寫點東西,我就會覺得那是一個可以發生某種可能性的機會。我並不會刻意把這些事情拼接成某種完整的「創作身份」。

對我來說,人生像一條不斷分岔的小路。只要事情還在找上門來,我就還有機會成為另一個版本的自己。我曾經遇到一位越南的療癒者,他說他想教我一些東西。但當時我的人生走向了另一條路。直到現在我偶爾還會想:如果當初跟他走,會發生什麼呢?

我相信,一切都不是固定的,關鍵是保持流動的狀態。我有很多出口和方式去表達,所以從不會感到無聊。但與此同時,我也沒有明確的目標或野心。我的生活更像是貼近想象力而展開的,不是為了做這做那,而是想看想象力能把我帶去哪裡。

我常覺得,想象力本質上是無政府的,而生活總是傾向於走向保守。但我寧願活在那種不確定、不設限的邊緣地帶。

AZ: To many students, you are like a mentor figure, in what way do you think you have influenced them? What would be the advice you would give to those who are practicing or want to try?

JM: There are many ways of being-with, and not having much to say, or do, is one of them. Sometimes it is what you don’t say that can have the strongest impact.

AZ: 很多學生都把您看作是一種「人生導師」的存在,您覺得自己是如何影響他們的?對那些正在創作、或者想要開始的人,您會有什麼建議?

JM: 我覺得,「陪伴」有很多種方式。有時候,其實你不需要說太多、也不需要做太多。很多時候,真正留下印記的,往往是你沒有說出口的那部分。

AZ: How has the UK art education changed in recent decades, from your experience?

JM: The most noticeable change that has happened to education has been the infiltration of a business ethos into the overall apparatus under the pretext of efficiency and value. What is clear is that students are expected to pay more in proportion to receiving less. It is so blatant in this regard that it barely merits intellectual debate, but it does place academia in some peculiar knots of compliance within the institutional matrix. If you could for a moment try to imagine the growth of the creative industries in the late Modern period without the impact of art education, then it provides an idea of the potential returns which have accrued in relationship to this sector, but then of course it is difficult to find empirical measure for this. The abstraction at the root of art education is the attempt to break with the habitual to create new forms. The pursuit of beauty is nothing but the desire for the difference between the given value form and the aesthetic form, which is in turn the seed of difference within life itself Without the generation of difference then there is an incline towards economic entropy. The beauty code is also an ethical code but what is needed is a new way of thinking about the value form and its relationship to measure rather than being subordinate to it. At the centre of such a project is an ethics of resistance to what is.

AZ: 您在英國藝術教育領域耕耘多年,您怎麼看過去幾十年來它發生的變化?

JM: 我覺得最明顯的變化是「商業邏輯」滲透到了教育體制中——表面上是為了「效率」和「價值」,但實際上它讓整個教育系統變得僵化。現在的學生學費付出更多,得到的卻更少。

這個問題已經明顯到幾乎不需要辯論。但它確實讓學術界陷入了某種自我妥協的狀態。在制度之中,我們變得很難自由地談論真正重要的東西。試著想象一下,如果沒有藝術教育,現代的創意產業還會是今天這個樣子嗎?這個問題本身就足以說明它的價值。藝術教育的本質,其實是在打破習慣,嘗試創造新的形式。

我們常說「追求美」,其實追求的是一種「不同」——一種打破既定價值結構的可能。這個「不同」也是生命的種子。如果世界只剩下單一的邏輯,那我們只會越來越耗散。

「美」的背後,其實也是一種倫理。而我們需要的是一種新的價值觀,去重新理解「衡量」與「價值」之間的關係——而不是永遠服從於它。要做到這一點,就必須有一種對「現狀」的抵抗精神,這也是藝術教育最深的根基。

AZ: Since your first touch with art or the art world, what has been changed profoundly compared to nowadays?

JM: When we evoke the art world there is something monstrous contained within any image we might care to construct of it. Rather than being subordinate to the discourses of aesthetics or art history, it is a form of power structure that determines its own outcome and sense of purpose, which implies not so much the autonomy of art, but rather the autonomy of the apparatus of art. The art world is a reiterative machinery for its own replication and this is what it learns from art itself. It is both persuasive and abject at the same time and necessarily double because of this. Contemporary art world is both highly transparent and opaque and as a consequence of this, assumes a double identity. Therefore, it is drawn from or out of figures which are not of its own making but is the demonstration of the power to find circulation with entities which might be supposed to be alien to its purposes. Its art is thus elsewhere to art and is, instead a form of art of business. What art promises business is a form of value that is elastic and there is a desire to replicate this principle in a broader sense. It is like having a way of linking magic to the value form. This magic cannot be seen because it is lodged within the futural aspect of art. This is why art attracts money to it. The project of modernist art was to strip the symbolic function of art with its connection to great expense vested in it, and to understand instead, just how the mostly lowly objects might become the most valuable. This is why early modernist art was fascinated by alchemy.

AZ: 那從您最初接觸藝術,到如今的藝術世界,您覺得發生了哪些最深刻的變化?

JM: 每次我們說起「藝術世界」,這個詞本身就像一個怪物,裡面包含了很多複雜又矛盾的東西。現在的「藝術世界」早就不再只是關於藝術本身,它更像是一個權力結構——它設定自己的規則、自我複製、自我運轉。

這不是藝術的自主性,而是藝術機制的自主性。它學習藝術的方式來重復自己,既有誘惑力,也有某種令人不適的部分。

今天的藝術世界是高度透明的,同時也極度不透明。它在這種「雙重身份」中運行。它往往不是用自己的方式去定義什麼是藝術,而是依附於某些原本並不屬於它的東西,從而證明它能與之對接——這其實就是「藝術作為商業」的變形。

為什麼商業世界喜歡藝術?因為藝術擁有一種「可變動的價值」,一種像魔法一樣的流動性。他們想把這種魔法複製到更廣泛的系統中。這種魔法肉眼看不見,它藏在藝術的「未來性」里,也正因為這樣,錢才會被吸引過來。

早期的現代主義藝術想做的是拆解象徵性的價值——那些背負巨大代價的藝術品能不能變得普通?能不能是「低微之物」才最珍貴?這就是為什麼他們會對「煉金術」那麼著迷。

AZ: Many people would feel confusing when encountering contemporary art works, what is your experience or attitude about it?

JM: Art is either in common with all other things or is the exception of the rule to all other things and this in turn are the two main entry points to it as an activity. We need to understand such a difference between exception and in common. Exception creates rupture within the fabric of life whereas being in common adds to the sense of the already of this fabric.

AZ: 很多人面對當代藝術時都會感到困惑、無所適從。您怎麼看這種體驗?

JM: 我覺得藝術有兩種狀態:一種是和所有事物都有聯繫,一種則是完全例外、超出所有常規。這兩種狀態,其實是我們進入藝術世界的兩種方式。「例外」會打破我們對生活的預設,撕開常規;而「共通」,則讓我們感覺世界是連貫的、熟悉的。我們需要意識到這之間的區別才能真正理解藝術的存在。

Interview by Michelle Yu

採訪及撰文 x 余小悅