Text by Katie Hill

… ‘as lowly as mere objects’

……“如單純之物一般卑微”

You might ask the question: ‘what is an artwork?’

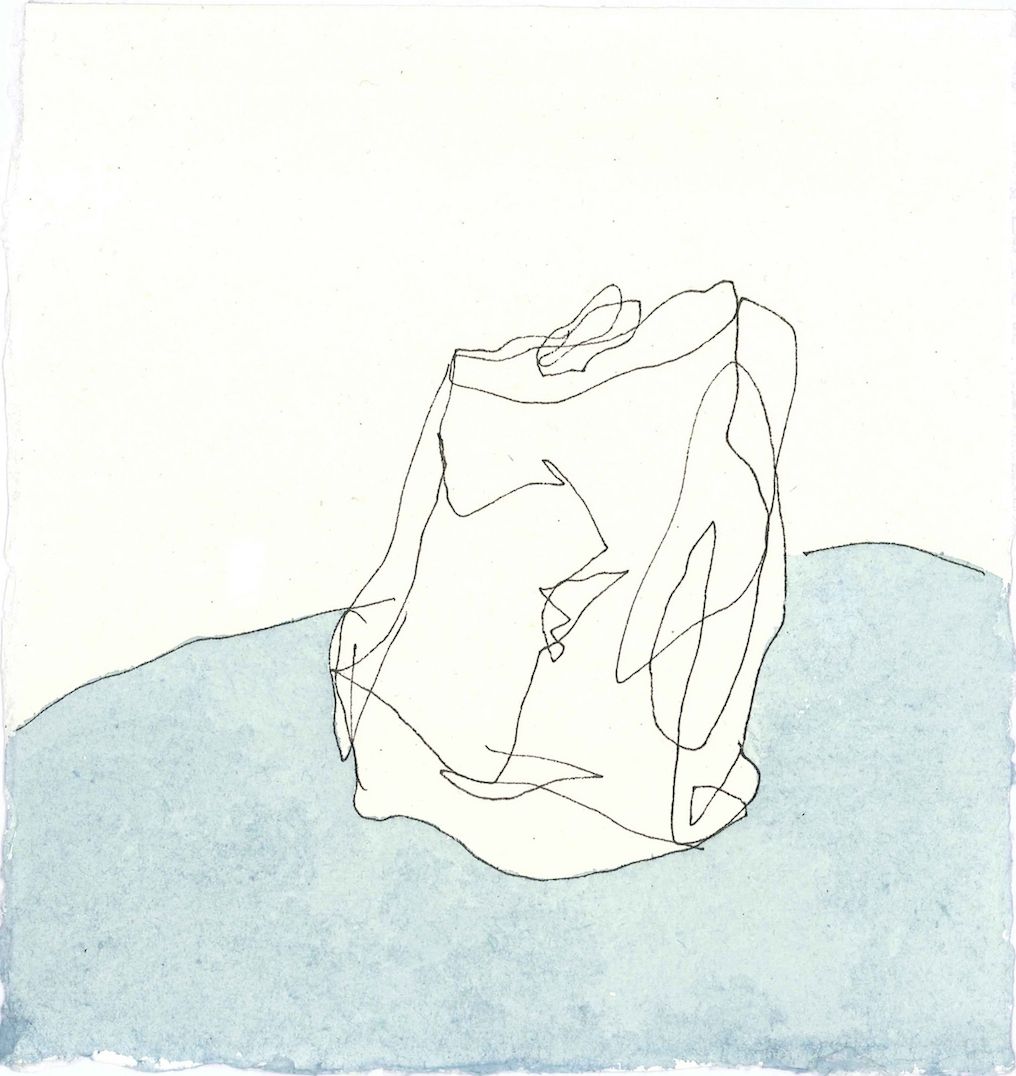

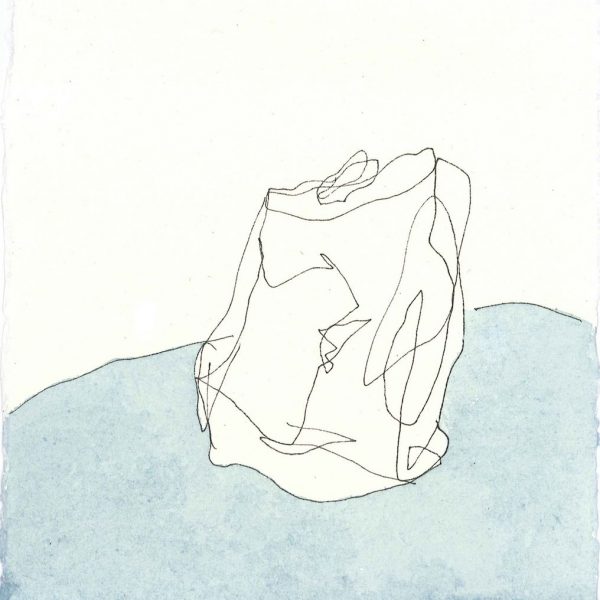

Start with an everyday object, something you barely notice – a free newspaper left on the tube, a bench, a packet of cigarettes, nails or pieces of debris: wood, wire and string. Small insignificant things that form the backdrop of life as we pass through it on a daily basis constitute the central component of Sun Yi’s work in the past couple of years, running through the materiality and form of his practice. Drawing is at the heart of his practice as well, as a fundamental aspect of cultural expression connecting low and high art, East Asian and Western cultural traditions. The works are under-played, almost whittled down like a rough piece of wood, worked on and yet left barely discernible as aesthetic objects/art works in their execution and presentation. They are subtly laid out below the surface, striking a bass note beneath the main tune.

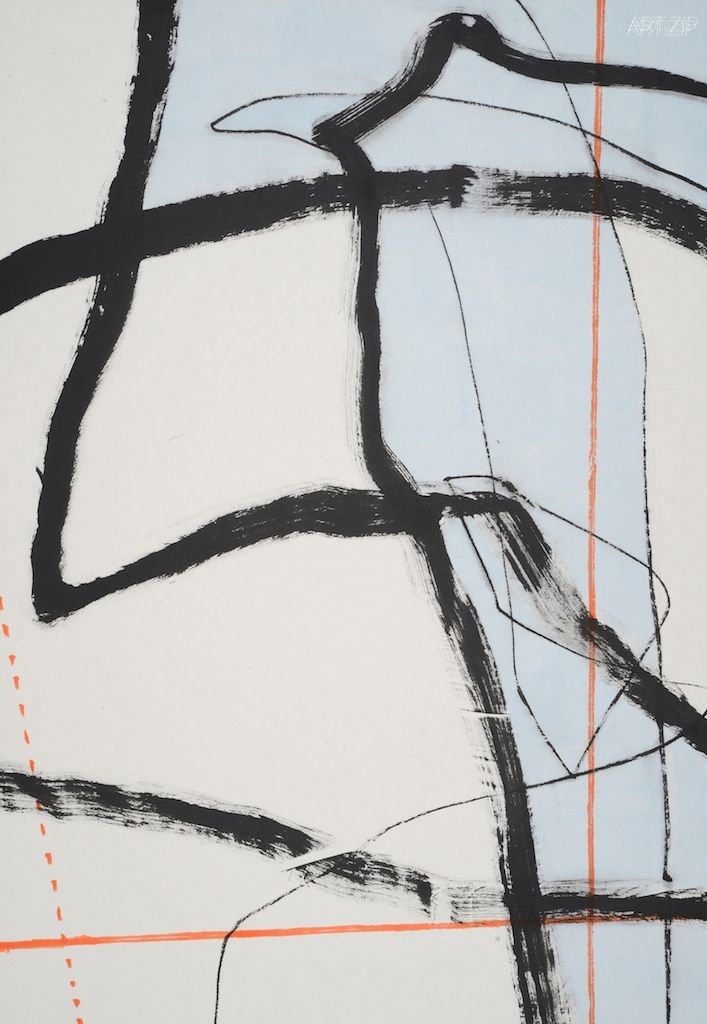

Sun Yi has practised calligraphy since the age of five and more lately trained in ink painting in China. As a child, he was requested to learn, initially in order to ‘sit still’. With this background, his discipline is embedded in different aspects of Chinese culture, such as the constant search for a kind of ‘imperfection’ that is philosophically in tune with Daoism or Chan Buddhism. Humility and acceptance are valued above any outward display of ego or spectacle, current values in our age of late global capitalism and neo-liberalism. In London, these values have fused with other philosophical thinking and in conversation, Sun frequently mentions philosophers such as Kant, Wittgenstein and Agamben, amongst others, showing a wide range of intellectual engagement in issues of taste, value and language.

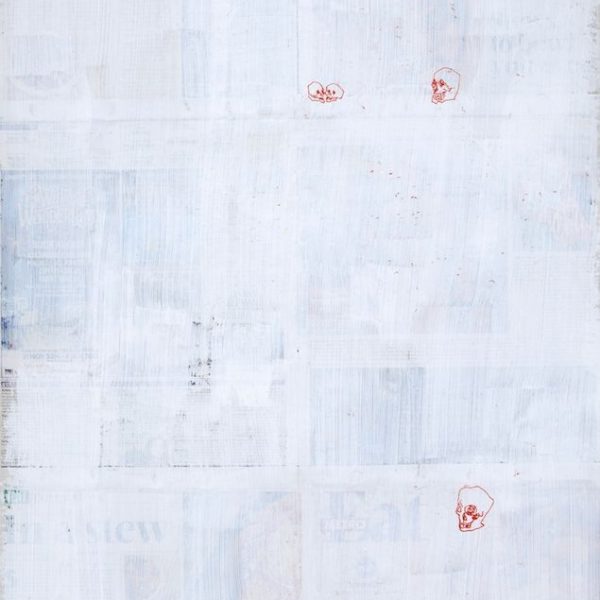

In London, his practice has evolved out of this background, accumulating understandings of liminality, tensions and paradoxes that are the push and pull of forces and structures in society and culture. Formally, his work pursues a dialogue across different artistic vocabularies from China and the West, making connections with drawing, painting and sculpture as integral aspects of cultural production across time and space. Sun Yi’s series of newspaper works manifest in a variety of ways as drawings, sketches, sculpture and objects posing questions about knowledge systems, and society’s propensity for story-telling through visual messages in the contemporary world of throw-away media.

你也許會問這樣一個問題:“什麽東西算得上是藝術品?”

日常物件,那些你幾乎不會注意的東西——隨手擲於地鐵上的免費報紙、板凳、一包煙、鐵釘或木屑、電線、繩子等等雞毛蒜皮。這些構成我們每天生活背景的不起眼物品就是孫毅過去幾年藝術創作的中心素材,貫穿了他整個藝術創作的選材和形式。同時,繪畫也是他藝術實踐的中心元素,作為一種文化表達的根本手段,聯系著低俗藝術和高雅藝術、東方和西方文化傳統。他的作品含蓄克制,幾乎就像是一段粗糙的木頭,雖然加工過,但從技法和外觀上幾乎看不出來是被賦予了審美觀念的藝術品。這些作品微妙地扮演著和光同塵的角色,彈奏著襯托中心旋律的低音部。

孫毅自五歲起練習書法,而後學習中國水墨畫。孩提時的他首先被要求學會“靜坐”。有著這樣的背景,他的紀律性便根植於中國文化的各個方面,比如,孜孜不倦地尋找“不完美”這種與道家和佛教禪宗哲學相吻合的特質;更注重謙遜和逆來順受,而不是追求自我的外在展示或誇張的表演,而後者恰好是當下後全球資本主義和新自由主義的價值觀。對於現身處倫敦的孫毅來說,這樣的價值觀已和其他哲學思想相融合。在談話中,孫毅經常提及康德、維特根斯坦、阿甘本等哲學家,這體現出他對品味、價值和語言等智識領域有著廣泛的涉獵。

在倫敦,孫毅的藝術實踐已經不再局限於傳統,他增進了關於閾限、張力和悖論的知識,這些概念正是推拉社會和文化進程,也是構築其結構的力量。形式上,他的作品是一場中西藝術話語的對話,其中涉及的素描、繪畫和雕塑是他穿越時空進行文化生產的重要一環。孫毅的報紙作品系列以諸如素描、速寫、雕塑和物品的形式呈現,針對的正是當下這個“隨手丟棄”媒介充斥的世界,對人們的知識系統和社會對於采用視覺信息進行敘事的偏好發問。

—

Extraction

On the surface of it, they are simple: sketches in black ink are formed by drawing through, small visual segments are extracted and traced, pulled out as little tableaux vivants, set against a plain white ground, with gesso brushed in broad strokes whereby all other contextual information is erased in a painterly gesture. The materiality of this background is significant: gesso is used to prepare the canvas but it is also a sculptural material and in this work it seems to be a deliberate play across media and function, a subtle yet traceable mark of artistic legacy lying below the surface as a platform for the images. As sketches they can be perceived as extracts, in that they are redrawn from the ‘real’, becoming reanimated as universal, non-specific figures, with overlapping functions of capturing the subject in the classical European sense and capturing the idea in the Chinese tradition of literati painting. In this case the drawing is perhaps connected to the idea of ‘Xieyi’ (寫意) in Chinese painting, literally ‘write meaning’ but with the sense of ‘inscribing the essence’, connecting the mind or the imaginary with the formation of a visual image as the expression or translation of an idea.

What is left takes us back to drawing itself and visuality, as though the process has been undone – deconstructed, simultaneously produced and de-produced as it were. They connect to the hand (off the printed image and back), and the head: are they in the artist’s mind and how do we ‘read’ them? As contemporary meditations, these works combine a sort of classicism with a take on contemporaneity and media information saturation. At this moment, print media is free precisely because its value has been reduced to nothing with the rise of digital. Perhaps print itself reverts to a classical status in the 21st century as an outmoded form of modernity.

The flip side of the paper is also interesting: showing both sides allows them to become sculptural objects that you need to walk around. Hung suspended, they cut across into our vision physically intervening in space. We are shown pages of everyday, often sensational or horrific stories with headlines and photographs: street protest, murder, suicide, domestic violence, but sometimes simply the banal face of bald consumerist capitalism, showing advertisements of smiling, product-bearing figures. Again the page is pulled out of context, yet there is a sense of currency, of fresh news that is due to become historical at some point in time (when does ‘history’ begin?). It is one part of a whole, usually embedded within a format that is designed for quick consumption by anyone while on the tube or bus, to be discarded or thrown away until another appears the next day, and so on and so on. Sun’s process of extraction might be random, but like the news, there is process of selection and patterns emerge, as images somehow take on epic narrative-forming roles in their production of our shared contemporaneity, answering to Anderson’s reflections on ‘imagined communities’ borne out of mass vernacular literacy.

The pictorial selection signal a bigger political framework through which we form global communities of shared response, such as the episode of a black man being shot down cruelly by a policeman in America as he runs away unarmed. His only crime to have a missing taillight on his car. His fate is shockingly revealed in the appalling capture on camera that seals the fact permanently in our eyes and imaginations. Sun Yi takes this into the work, but it is part of the daily ritual, it is the response and understanding of it is what magnifies its significance. Whilst this episode is echoed with many others (jihadist youth leaving the UK for Syria, children who have been murdered), through the series of images extracted on a daily basis over a period of two years a broader picture emerges and is also simultaneously erased in the drawing. What do we know? How much do we understand? How do we process our world?

In his use of the everyday over time, Sun also deals with the aspect of time as a central part of his practice. Units of time are measured – a day finishes, another begins. Executed over a period of two years, the work is framed through real time experience as an everyday habit, discipline even, of how we live our lives, via this reading of the news. News itself becomes a framework, the framework even. A ritual marking time and our connection to the world, as we switch on the radio, or TV, pick up the paper, to browse through and share the daily horror. Part of the modern world, these little rituals are ubiquitous, transcending cultural difference. In Eagleton’s words, ‘aesthetic intersubjectivity adumbrates a utopian community of subjects, united in the very deep structure of their being’. Calligraphy is echoed here in a daily, meditational, inward practice. As a practitioner, Sun is utilising these patterns of habit in his own process as an artist, engaging the casual acts of reading, viewing, sitting, which lies between the visible, the invisible, the taking in and the leaving behind, in a subtle interplay of our relational world and the very structures that bind us together. The cyclical nature of time in Chinese culture is key to this process and in Sun’s view of the world.

精揀

表面上看,這些作品很簡單。藝術家用黑墨描畫成速寫。小的視覺元素被精揀出來,然後進行描畫,組成一系列“小活人畫(Tableaux Vivant)”,背景則是平淡的白底,用石膏大筆塗抹,用繪畫的方式擦除背景信息。這種背景處理的用料是很重要的:石膏用於預制畫布但同時也是雕塑原料,在這組作品裏,石膏的選用似乎是故意地在媒介和功能中玩謔,這個元素是包含藝術蘊含的,它處於表層元素的底層,起到襯托圖像的平臺作用,從而給整個作品增加了微妙卻有跡可循的藝術味道。這些速寫也可以被看成是“精揀”之作,因為它們是從“真實”中萃取的,然後重新賦予它們生機,而成為普遍的、非特異的個體,而這其中恰好體現了兩個重合的藝術觀點——歐洲古典主義的寫物傳統,和傳統中式文人畫的寫意傳統。從這個角度來說,這些作品或許確實是有中畫的“寫意”味道的,“寫意”這個詞除了“傳達意義”,還有“抓住精華”之意,即把心靈或虛構之物與視覺圖像相結合,傳達或傳譯某個意義。

孫毅的畫近乎可以說是未完工的——解構的,創作和反創作同時進行,而畫面上剩下的東西把我們帶回到了繪畫和視覺性本身。它們讓我們聯系起“手”(不接觸圖畫和背面)和“頭”:這些東西是否存在於藝術家的心裏?而我們怎麽去“解讀”?作為一種當代觀照,這些作品結合了某種古典主義和當代性以及媒體信息飽和。現今,印刷媒體之所以免費,完全是因為數字媒體的得勢而使其變得毫無價值。或許,印刷本身在21世紀的今天確實回到了其“經典”的地位,只不過是作為過時的現代性“經典”。

作品的背面也一樣有趣:正面和背面同時展示使其成為雕塑物件,因而參觀者必須前後走動才能欣賞整件藝術品。懸掛而下的作品阻斷了空間,闖入了我們的視野。展示在我們面前的,是刊登在報紙上的日常報導,通常是帶著大標題和照片的轟動或聳人聽聞的故事: 上街遊行、謀殺、自殺、家庭暴力,但有時也只有赤裸裸的消費資本主義的乏味面孔,廣告上微笑的臉蛋、帶著各種數字的產品等等。這裏,這些頁面都被抽離出上下文,但還是有一種“時效”的感覺——新出爐的新聞總會在某個時間點成為歷史(“歷史”是怎麽開始的?)。這些只是整體的一部分,它們經常有著固定的模式,它們就是為那些乘地鐵或者公車的人的快速消費設計的,就是要隨手扔掉,因為明天很快就會有新的出現,如此往復。孫毅的精揀過程也許是隨機的,但就像是新聞,總還是會有選擇的過程,總還是會有模式的出現,因為不管怎麽說,圖像總是能夠帶來一種史詩般的敘事——在它自身的產生過程中形成與我們共時存在的角色,回答安德森對於大眾本土文化所擔負的“想象的社區”的思考。

圖片的選擇也示意了一種政治框架,我們正是憑借此形成一種全球社區,對某些事件有著共同的回應,比如說,在美國手無寸鐵的黑人在逃跑途中被警察殘酷擊斃,他唯一的“罪”便是車的尾燈掉了,而他被擊斃的駭人聽聞的命運便被攝像機固定下來,同時永久地封印於我們的視野和想象裏。孫毅也把這個事件帶進了他的作品裏,但這只是日常例行公事的一部分,對作品的回應和理解才是顯示作品重要性的元素。這個事件和其他事件雖然有著呼應的關系(伊斯蘭年輕聖戰士離開英國前往敘利亞,被謀殺的孩子等等),隨著兩年間每天都有圖像被抽取出來形成一個系列,一幅更大的圖景便出現了,同時很多圖景也被擦除了。我們到底知道什麽?我們能理解多少?我們該怎樣理解我們的世界?

盡管在藝術實踐中,孫毅青睞長期使用日常的東西,但是時間本身也是他創作的一種中心元素。時間的單位測量——舊的一天結束,新的一天開始。作品實施了兩年,已經被真實的時間經歷帶上了烙印,就如同是一種日常習慣、紀律,甚至是通過這種閱讀新聞的方式生活一般。新聞本身甚至成了一種框架。當我們打開收音機、電視機,取報紙,瀏覽和共享駭人聽聞的新聞時,它成了一種標記時間以及我們和世界聯系的儀式。這是現代生活的一部分,它是普遍存在的,獨立於文化差異。用艾靈頓的話說“美學主體間性勾勒出主體的烏托邦社區,在其存在的深層結構中聯合”。書法,在這裏以一種日常、冥想、內省的實踐呼應著。我們的世界是個關系世界,同時,把我們聯系在一起的卻確有一個結構,在這兩者的微妙相互影響中,作為一名書法從藝者,孫毅正是在他的藝術實踐中使用了這些習慣模式,他隨意地閱讀、觀看、閑坐,介乎可見和不可見,攝取和摒棄。中國文化的時間循環觀是孫毅的創作和世界觀的關鍵。

—

Questionable objects

In his sculptural and other object-based works, drawing is still present. Lines, composition, material are pulled around, extending the act of drawing into three-dimensional space. Nails and wire filaments are placed, again casual/not-casual, whether by chance or deliberate placement, we are not quite sure. The benches are disarmingly simple. Public furniture normally placed for convenience, to be sat on while you eat your lunch, wait for your friend, and so on, are upturned illogically and strewn minimally with ribbons, as though ‘wrapped’ but ineffectively, as a signal of difference, or in Derridean terms ‘différance’, in which a small alteration causes a shift of focus or meaning. How are we meant to understand them? Function is denied in favour of a philosophical and aesthetically positioning as sculptural form. Space is called in, transformed through this misplacement, calling the ‘natural’ placement as an unnoticeable landscape to attention. In other works, there is a playful back and forth of form and function: a library is completely stripped of its book spines, as all the books are turned sideways, or wrapped in plastic, rendering their contents unreadable. A chair is photographed suspended halfway up a wall attached to a bookshelf in a simple visual trick of perception. Large rectangular blocks of ice are laid to rest inside a hole in the ground, the solid freezing object due to melt and fuse back into the land as water.

值得懷疑的對象

在孫毅的雕塑和其他以藝術為基礎的作品中,繪畫依舊存在。線條、構圖、材料都被結合起來,使得繪畫的藝術擴展到三維的空間。作品中放置著鐵釘、電線和燈絲,隨意地刻意地,隨機擺放地或故意而為,我們無從得知。凳子看起來友善而簡單。一般便民使用的公共設施——吃午飯時、等朋友時你都可以坐在公共座椅上——卻被孫毅打破正常邏輯顛倒過來,稀稀拉拉地撒上帶子,仿佛椅子是被糟糕地“打包”起來,以此來暗示“差異”,或者說是德裏達的“延異”——細小的改變引起焦點或者意義的轉變。我們理應怎樣去理解這些作品?作為一個雕塑形式,其功能被否定了,取而代之的是哲學和美學的立場。空間的概念引入了,在他的誤置下產生了轉變,使得不起眼景觀的“自然”裝置獲得了關注。在他其他的作品裏,形式和功能的關系總是調皮地變動著:在一所圖書館裏,書脊全部不可見——書本都是橫著擺放,或用塑料包裝起來,這樣一來讀者完全讀不到書裏的內容。略施一點視覺小詭計,便把一把椅子拍攝成連著書架懸掛於半墻高的地方。大大的長方形冰塊放置於地上挖開的洞中,可這冷冰冰的東西總歸要化成水溶進地裏。

—

Exchange

The One Cent project is a group of objects or paintings presented in a group as a proposition for exchange. The objects and the coin (also an object) become interchangeable in a value system that levels the field of values to a nominally flat plane. Here the art market is subtly invoked in a wry lowering of the stakes, as the question of materiality and culture is called in, in which artworks are shown up as exchanged in a distorted value system of cumulative capital and market forces.

Ultimately Sun’s works are an exploration of value (as much as) aesthetic/cultural, social, economic, in the Bourdieuan sense of ‘habitus’, our very existence in a society is threaded together through value systems(“is” should be omitted?); a news story cheaply narrating a life lost sometimes in appalling circumstances, but the story itself and the image is also dispensable, disposable, to be cast away until the next comes along. Equally ‘high art’ is set aside in Sun’s work, for small seemingly insignificant sketches that give back value through a small retrieval. The sketches, as meditational crossing and unravelling of connections, the daily act of calligraphy touches the surface lightly, allowing them to hover into view – to linger, reflect and reconnect.

Sun’s is the opposite of spectacle or the often heightened language of contemporary art vocabulary in the mainstream art world. Perhaps in response to an earlier generation of forceful gestural work or giant-scale installations, he looks towards Twombly, On Kawara or Anastasi whose works made different kinds of connections through drawing or marking time, as modes of touch, sensibility, sensory experience or acts of memory.

He works back into the underbelly, retrieving and considering what runs through society, manifesting itself in barely visible form, yet revealing disturbing ideologies and questionable modes of consumption. In a stratified economic value system, lowest common denominators are brought in such as pieces of wood, nails, string (dyed with ink), penny coins, scratching the base of our environment, showing a deep understanding of the ‘ordinary’ as essential and sustainable aspects of life.

Sun calls drawing ‘an inexplicit and attractive object’ and perhaps this neat phrase describes his mode of practice. There is a kind of existentialist formalism to his works, as they seem to stand as understated ‘facts’, poised between an abstract geometry and a more specific everyday reality. The lines he draws, both literally and metaphorically, intervene in space in dialogue with languages of art and our spatial existence (difficult to understand). To finish, we might consider one of Sun’s simple, disingenuous works: an asymmetrical white frame – a found object – upended, placed in the middle of a narrow, empty side street in London, interrupting the space between the tall, Victorian buildings producing vertical and horizontal lines of connection. In the words of Ackbar Abbas, it presents: ‘not the new but the old as unfamiliar: this is one of the paradoxes of any-space-whatever’. This work is deceptively simple; it draws together many of Sun’s interests: performativity, material, geometry and formalism, positioned in a random ready-made place, redolent of time, culture and history.

交換

所謂的《1分錢計劃》是一組物件或者繪畫作品,旨在鼓勵交換。物件和硬幣(也是作為物件)可以進行互換,在這樣的價值體系裏,價值被校準到同一水平。由於物質性和文化問題的引入,藝術市場以不正常的低價向買家卑躬屈膝——藝術品在累積的資金和市場力量所致的扭曲價值系統中以交易的形式出現。

歸根結底,孫毅的作品是對價值的探索,也是對布迪厄意義上的美學、文化、社會、經濟“習性”以及由價值系統交織的社會中我們存在的探索;一個描述生命隕落的新聞事件經常廉價地裝扮得聳人聽聞,然而報導本身、連帶著圖像都是可有可無、一次性的,新的一到舊的就可以置之腦後了。同樣地,“高雅藝術”在孫毅的作品中還是留有地位的,因為那些看起來無足重輕的小速寫實際上通過小小的交易重獲了價值。這些速寫,作為日常書法冥想的交織和意義聯系的澄明, 輕輕地跳躍於作品表面,盤旋著進入我們的眼界——流連著、反思著、重構著。

孫毅是當今主流藝術世界宏大高調話語體系的反面。也許是為了回應力度氣度非凡的前代身體作品(Gestural Work)和巨型裝置藝術,他看齊的對象是托姆布雷(Twombly)、河原溫(Kawara)或阿納斯塔西(Anastasi),這些藝術家的作品通過繪畫或標記時間造成了各種聯系,作為觸覺模式、感性、感官經驗或記憶行為。

他的創作有感而發,接收並考慮著社會上發生的事情,他的作品幾乎不可見,但卻揭示著令人不安的意識形態和可質疑的消費模式。在層壘分明的經濟價值體系裏,他引入了最小公分母,如木片、鐵釘、繩索(墨水上過色的)、硬幣,這觸及到了我們生活的基礎,展示了對這些作為生活中重要的可持續一面的“尋常之物”的深刻理解。

孫毅把繪畫稱為“模糊卻又吸引人的對象”,或許這個簡潔的詞匯也精確地描述了他藝術創作的模式。他的作品似乎以輕描淡寫的“事實”存在,既有抽象的幾何元素,更有具體的日常現實元素,因而有著某種存在主義的形式主義。他畫的線條,憑借藝術的語言和我們的空間存在,或實際或隱喻地介入了對話空間。作為結尾,我們不妨考察一下孫毅簡單而隱晦的作品之一:一個不對稱的白色框架——一個偶得的物件——顛倒放置於倫敦大路邊狹窄的小巷中,打破了高高聳立的維多利亞建築構成的橫平豎直線條的聯系。如阿卡巴·亞巴斯所言“不熟悉之物非新物,而是舊物:這是所有空間的悖論之一”。這件作品簡單得近乎狡猾,它體現了孫毅的許多藝術旨趣所在:表演性、物質性、幾何性和形式主義,隨機置於現成的場地,發人關於時間、文化和歷史的深省。