2. The Denial of Authenticity

In the art market, the opinions of artists’ authentication committees and estates can carry overwhelming authority, effectively making or breaking the value of an artwork. In countries like France, artists’ heirs have a legal right to confirm or deny authenticity of artworks, thereby cementing this authority (24). Yet what happens when this authority seems to have been exercised arbitrarily in defiance of scientific evidence and provenance?

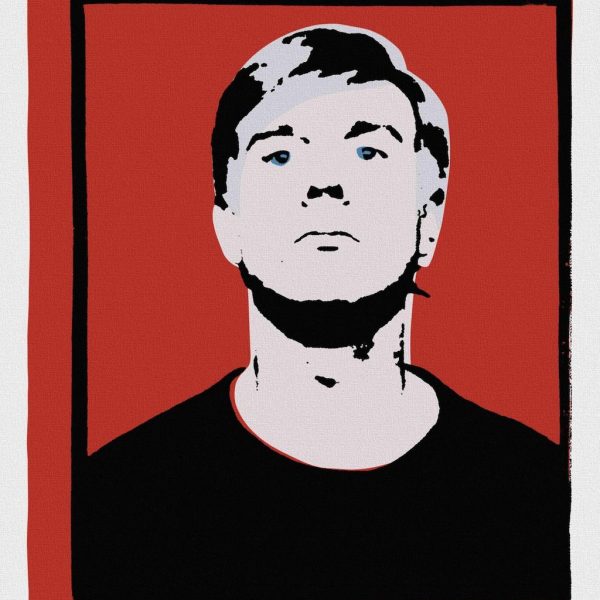

The controversies surrounding the authentication procedures of the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board and its apparent lack of transparency are a striking example of the types of dispute that can arise. The Warhol board has the invidious task of regulating the authenticity of the artist’s oeuvre, made difficult by the ease with which Warhol works can be fabricated (as seen in the Pontus Hulten controversy). In fact Warhol’s work is based upon the industrial-style reproduction and repetition of images, and even the questioning of the regime of artistic originality, including the delegation of artistic production to his assistants, for example, Gerard Malanga. In addition, Warhol’s own practice of authentication was inconsistent; he sometimes signed his works and in other cases issued certificates, while on occasion he did not certify or sign his works at all (25).

The Warhol board aims to provide certainty in this difficult market by investigating the authenticity and provenance of works submitted to it and by certifying those works that it deems to be original Warhols. Its determinations have become so important that it is very difficult for an owner to sell, at least an important and valuable work by Warhol, in the market without its certification.

In 2009 a disgruntled English collector, Joe Simon-Wheelan, issued anti-trust proceedings for unlawful restraint of trade in the New York courts against the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board and Foundation for abuse of their position as a monopoly (26). Wheelan had submitted to the board the silk-screen painting Red Self-Portrait (1985), which it refused to positively authenticate. The work had been signed by Warhol, and its provenance established a direct link with the artist; it had even been authenticated by the Warhol board in 1987. Controversially, the board does not provide reasons for its decisions, maintaining that such transparency only assists those who want to fake Warhol’s work. It did not do so in this case, and it destroyed Wheelan’s artwork by imprinting “DENIED ” in large letters on its back.

It is also difficult for owners of artworks to rely upon other legal courses of action. One route is to claim that the authentication board or art expert have slandered or disparaged the goods in question. In Hahn v Duveen (1929) (27) the claimant, Mrs Andreé Hahn sued the eminent Leonardo da Vinci scholar and dealer, Sir Joseph Duveen in the US courts after the latter had described the claimant’s painting to a news reporter as being a ‘copy’ of a Da Vinci – the original being in the Louvre. Duveen settled with the claimant for fear of establishing a dangerous precedent. Yet to succeed here a claimant must show that the defendant’s statement has been made maliciously or at least recklessly with regard to the truth. In addition, the claimant must establish that “special damage” has been caused to the economic value of the goods as a result of the statement.

In effect, an art owner would need to demonstrate that the authentication committee or expert held an opinion about the artwork that no reasonable person could hold. This is a very difficult task, particularly if a court gives latitude to the connoisseurship of the committee’s art experts. Proving loss or special damage—that is, the inability of the owner to sell the artwork on the market—is not straightforward either, as the US case of Kirby v. Wildenstein (1992) (28) demonstrates. Here the court rejected evidence from Christie’s that Daniel Wildenstein’s negative attribution of a painting led to a dramatic decrease in its value by requiring the claimant to specify actual people who were unwilling to purchase the painting at auction as a result.

Finally, many authentication committees ensure that they enter into “hold harmless” agreements with owners. In 2002 the New York State courts upheld such an agreement used by the authentication board of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation (29), preventing an owner dissatisfied with its negative attribution from claiming against the foundation on the basis that he had contractually agreed to waive such rights.

The cases discussed above reflect the difficulties that owners of artworks experience in using the law to challenge the machinery of the art world. Even if a court finds an artwork to be authentic on the basis of evidence it evaluates from art experts during a trial, it is uncertain how far the art world will take a court’s decision into account.

The US case of Greenberg Galleries et al. v. Patricia Baumann and L & R Entwistle (1985)(30) indicates the limits of the law in regulating the art world. In this case a group of art dealers sought to reject an Alexander Calder mobile, Rio Nero (1959), and claim damages from the dealer who had sold it on the basis that the work was not genuine. The claimants accepted the provenance of the artwork to be flawless but provided expert evidence from Klaus Perls (Calder’s exclusive US dealer for twenty-five years) based on his “knowledge and feelings” of Calder’s work that the work in question was not in fact genuine.

During the trial, the defendant relied upon counterevidence provided by another Calder expert, Linda Silverman (though not as eminent as Perls). They also established that the signature on the base of the mobile was almost certainly made by Calder. The court found in the seller’s favour but concluded that the Calder mobile had been re-assmbled so badly it did not correspond with the archival photograph documenting it. Despite the court’s verdict, the mobile has not been included in the Calder catalogue raisonné, and the dealers who bought it have apparently been unable to resell it since (31).

3. The Withdrawal of Authorship

The threat that an artist may withdraw authorship from an artwork is a relatively recent phenomenon. In one sense it is tied to the development of artists’ moral rights of authorship as reflected in different national laws. In France artists are expressly provided with the right to “repent” authorship from the artwork, though this is rarely used in practice (32). In another sense it is tied to the desire of artists to control the artwork after it has been sold, as well as to the artists’ political struggle with museums and the commercial art market. In the notes accompanying their programmatic “Artist’s Contract” (1971), Seth Siegelaub and Bob Projansky advise artists to withdraw authenticity from their work if it is not sold and resold by future collectors in accordance with the progressive rules of the contract (33).

There are two situations in particular where the withdrawal of authorship arises: first, a certificate of authenticity issued by the artist to accompany the artwork is lost by a collector or is stolen; second, the artist enters into a dispute with a collector, for example, concerning the artwork’s fabrication or payment.

With the rise of conceptual and minimal art (and the absence of the artist’s trace on the artwork), the certificate of authenticity has become a vital legal type of instrument both for artists to assert authorship and for collectors to verify ownership of artworks. It is no accident that artists like Carl Andre, Daniel Buren, Hans Haacke and Lawrence Weiner have constructed highly organized administrative systems around the issuing and replacement of their certificates (along with the numbering and cataloging of their works). Indeed Andre has gone one step further by creating a registry of his artworks that records changes in ownership as well as cataloging them (34).

It seems logical that certificates should be used widely in conceptual and minimal art, where a dematerialized work often consists of a set of written instructions or drawings on paper—for example, the wall drawings of Sol LeWitt—authorizing the owner to fulfill the work, or of prefabricated ready-made parts (for example, Dan Flavin’s light installations) whose construction is delegated to others. In these circumstances, what else can guarantee that an artwork is an original and not a fake or an unauthorized copy?

If the certificate helps to underwrite the authorship and value of a contemporary artwork, it also in a sense represents a sublimation of the authorship function into a form of property (the correlative assertion “This is an artwork” identified by Duchamp in his readymades), the act of designation of the artwork, which can circulate independently of the work or at least of its nature as an object. Rather than leading to the removal of the author or artist from involvement in the work, however, the certificate implicates the artist over time.

If the owner of the conceptual artwork does not possess a certificate of authenticity, then it is practically impossible for that owner to sell it, particularly at auction. Paradoxically this may apply even when an owner can establish in all other respects that the artwork is “original,” in terms of its creation and provenance. The owner of the artwork (the work’s instructions, material elements, or objects) then depends on the artist, gallery, or estate to issue a replacement. Most artists and their galleries are willing to oblige, particularly if they know the collector personally. (Despite its global reach, the art world consists of a restricted group of dealers and collectors.) Yet in certain situations they may refuse. Joseph Kosuth refuses to reissue certificates if they are lost or stolen, and Gordon Matta-Clark famously warned on his certificates that they would not be replaced (35). What can the owner of the artwork do in such circumstances?

Once again the legal system is pitted against the machinery of the art world. It is doubtful whether a collector could legally force an artist to issue a replacement certificate unless it has been expressly agreed in writing. One possible remedy for an owner lies in breach of contract, although the collector may not be in a contractual relationship with the artist (the owner could be a third party). Even if the owner were in a contractual relationship with the artist, it is not clear on what basis it could be implied that a replacement certificate must be provided since artists are generally not generally required to replace artworks in case of loss or theft.