INTERVIEWED AND TEXT BY 採訪及撰文 X NILS JEAN,SOPHIE GUO 郭笑菲

TRANSLATED BY 翻譯 x JOSHUA GONG 龔之允 HARRY LIU 劉競晨

IMAGES COURTESY OF X WHITECHAPEL GALLERY 白教堂畫廊

Electronic Superhighway (2016-1966) at the Whitechapel Gallery is a recap of the history of Internet art from 1966 to the present day. The show brings together multimedia works including painting, video, sculpture, and photography by over 70 artists to illustrate how network and computer technologies expand the definition of art. As a survey show, Electronic Superhighway encompasses the different art forms as technologically contingent to the diverse debates that net artists positioned in relation to socio-political environments both online and offline.

The interview with the curator Omar Kholeif reveals his curatorial strategies in presenting the exhibition in the way of ‘traveling back in time’, the rationale behind his visual negotiation between the virtual and the physical inside the gallery space, as well as his insight upon issues around democratisation of Internet art as he put together the varied kinds with different discourses.

在白教堂畫廊展出的《電子超級高速公路2016-1966》是對1966年以來的互聯網藝術史的一次簡要回顧。這次展覽聚集了由70余位藝術家創作的多種媒體形式的作品,包括繪畫、視頻、雕塑和攝影,展示了網絡和電腦科技是如何擴展藝術定義的。作為一次調研式的展覽,《電子超級高速公路》涵蓋了各種藝術形式,就如同科技的百家爭鳴一樣,網絡藝術家們把自己同時置身於在線和離線的社會政治環境之中。

這次與策展人奧馬爾·克萊夫的訪談透露了他“逆時旅行”式的展覽策略,他在處理展覽空間內虛擬和物理視覺之間關係的理念,以及他對關於互聯網藝術民主化問題的看法。

ART.ZIP: What is the genesis of this project?

OK: Up until a couple of months ago, I proposed the exhibition as something very specifically to do with the history of the Whitechapel as a museum of firsts. Opened in 1901, it often gives artists, from Robert Rauschenberg, to Frida Kahlo, and Jackson Pollock their first solo show as well as lots of artists who have engaged with new media, from Bruce Nauman, to Bill Viola, and to Chris Marker.

So I started thinking what the urgent discussions or debates of that specific moment were. I’ve been invested in the history of the Internet specifically and thinking about the context by which contemporary art has emerged in relation to that. I was very excited to think about the possibility of creating a framework that would historically examine and locate those practices.

So I proposed the exhibition with those in mind and as it developed over a number of years, the form started to take shape. It started of being a show that was very specifically about the digital but it really became a show much more about mapping the history of the Internet and thinking about networked technologies as opposed to purely about the digital, over the digital, and the composite part of that narrative and history.

I also wanted to think about the genesis of these movements— very specifically about experiments in art and technology in 1966, which was this event that happened one year before the ARPANET when Internet became a concept, to computer-generated drawings, to the replacing of the hand with the machine, to early interactive art. As we moved into the present thinking about the new aesthetic that had emerged in those digital spaces, we see that finally the digital spaces transfer into real world.

There are a lot of paintings and sculptures that look at those tensions. I worked with a curatorial advisory committee of four people: Ed Halter, Erika Bolsom, Sarah Perks, Heather Corcoran, each brought different expertise and I started with a very long list of over 200 artists and started to discuss who the key figures were, what the key works were and how they would spatially speak to the story.

As the show started to come together, I decided very specifically to run it backwards, to start in the present and the rational behind that had to do with thinking about how the history of the Internet is one that skews conventions. It is of so many innovations and diagonal criss-crossings that I thought, rather than a traditional historical route, was to start with the visual kind of cacophony of the present and then move back in time.

ART.ZIP: 這次展覽的來龍去脈是怎樣的?

OK: 直到展覽開幕的數月前,我才提議把這次展覽專門提出來講講白教堂畫廊作為先驗博物館的歷史。白教堂創立於1901年,它一直為許多先鋒藝術家舉辦首次個展,例如羅伯特·勞申伯( Robert Rauschenberg)、弗里達·卡洛(Frida Kahlo),傑克遜·波洛克(Jackson Pollock),還有許多利用新媒體創作的藝術家,如布魯斯·紐曼(BruceNauman)、比爾·維歐拉(Bill Viola)、克里斯·馬克爾(Chris Marker)等。

於是我開始思考那些特殊時期最迫切的討論或爭論時是什麼。我一直專注互聯網歷史的研究,並一直思考當代藝術興起與它之間的關係。我想嘗試建構一個框架,以歷史角度來檢視和挖掘這些藝術實踐的來源。

因此,我帶著這樣的理念開始策劃這次展覽,從構思到成型經歷了數年之久。展覽的雛形是專門針對數碼的,但最後它變成了一個繪製互聯網歷史的展覽,互聯網技術從與純粹的數碼對立,到超越數碼本身,還變成了敘述和歷史的組成部分。

我還想探索一些運動的起源——特別是1966年藝術與科技結合的實驗,這些發生在阿帕網(ARPANET)的前一年,之後才出現了互聯網的概念,電腦程序生成圖像,機器替代手工、早期交互藝術等等。當我們站在當今的立場來思考那些發展自數碼空間的新美學時,我們會發現數碼空間早已融入現實生活之中。

大量的繪畫和雕塑對這種緊張感作出了回應。我和策展顧問委員會的四人:埃德·哈爾特(Ed Halter)、艾麗卡·玻爾松(Erika Bolsom)、莎拉·普爾克斯(Sarah Perks)還有海瑟·闊克倫(Heather Corcoran)一起合作,他們都給個項目帶來了不同的專業知識。一開始我有一份超過200名藝術家的清單,然後我們開始討論哪些是關鍵的人物和作品,以及它們在空間裡如何呈現這條故事線。

當展覽快成型的時候,我決定用倒敘的方式來呈現,從現在當下的藝術開始講起。因為正是互聯網的發展歷史影響了故事的發展方向。我沒有選擇傳統的歷史敘述路線,而是採用大量的創新和交錯的方式,一開始進行‘嘈雜’的視覺呈現,再慢慢回溯歷史。

ART.ZIP: Is it not also maybe a wish to start with the technologies that might be the most familiar to the viewers, as a way of engaging them in a different way?

OK: In some ways it is about that idea of the immediacy of the media. Thinking specifically about the idea of the relevance of those technologies, from Instagram to Photoshop, to even Karaoke as the very kind of things that will automatically click to the viewer and give them an access point, or an entry point, was certainly something I was thinking about.

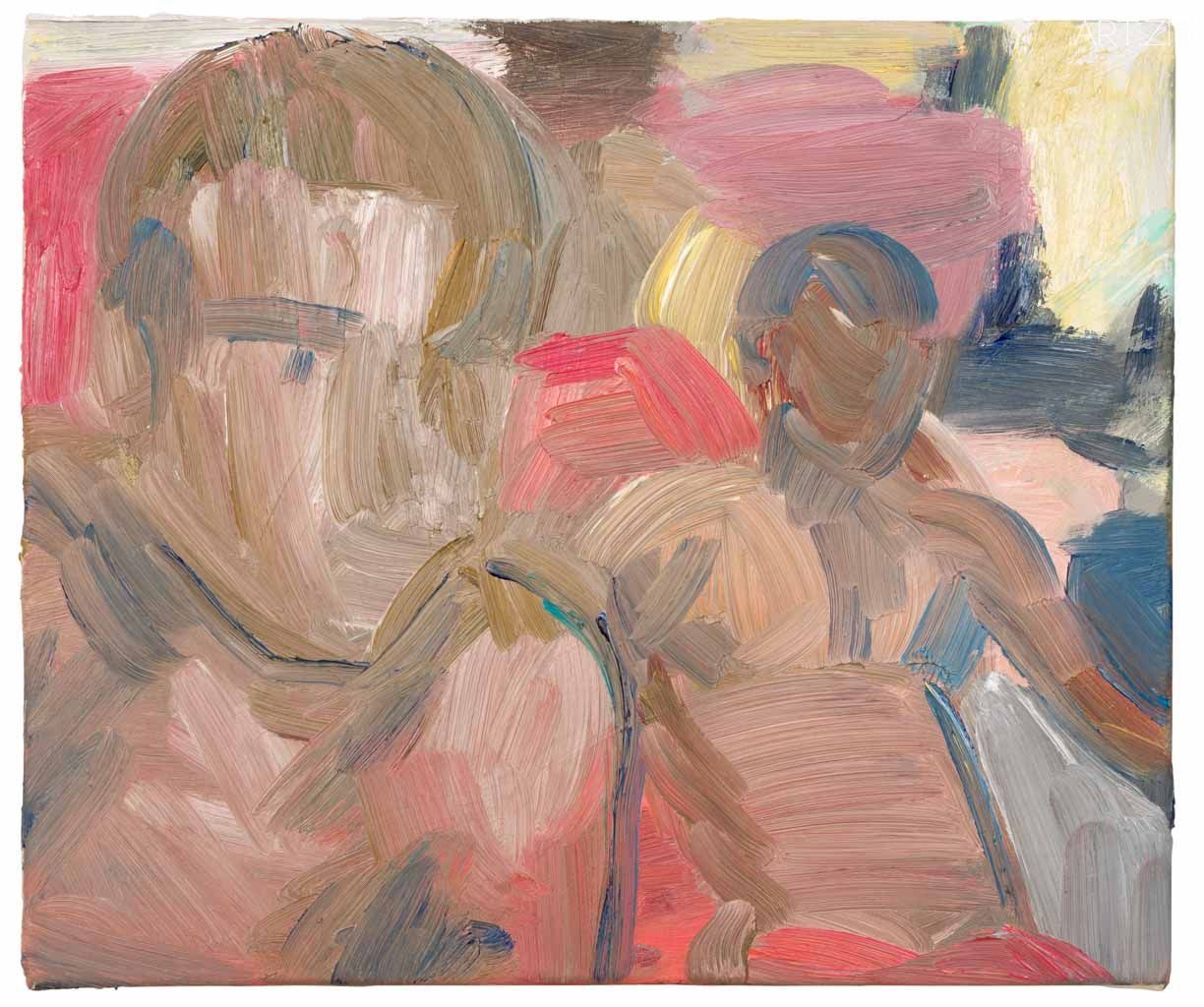

I’ve also been trying to be more critical of that space, and so I brought in a lot of paintings and sculptures that really seek to critique or examine those very contemporary technologies. For example, Celia Hampton’s chat random paintings is arguably a social media artwork because they are painted live as she was trying to hold these conversations. But her medium is painting and she is a very traditional painter. So at the same time I am looking at these familiar media or spaces, from what I believe to be a fairly unconventional perspective.

ART.ZIP: 那會不會也希望通過觀者最熟悉的科技開始,用別樣的方式來鼓勵參與?

OK: 在某種程度上這個展覽是著重於表現媒體的即時性。特別是這些科技與主題的關聯性,從Instagram到Photoshop,甚至是卡拉OK,這些事物都會喚起觀眾的共鳴,給他們一個理解作品背後觀念的切入點,這也正是我希望的效果。

同時,我也非常注重整個展覽空間的佈局,通過繪畫和雕塑作品的展示,我希望能夠對當下的科技展開一種嚴肅的討論和檢視。比如,西利亞·漢普頓(Celia Hampton)的隨機閒聊繪畫按理說是一件社交媒體作品,因為她需要和別人一直對話並同時進行即時繪畫。不過她作品的媒介仍然是繪畫,而且她也是一位比較傳統的畫家。所以我同時在用我認為的一種非常規的角度去觀看一些看似熟悉的媒介和空間。

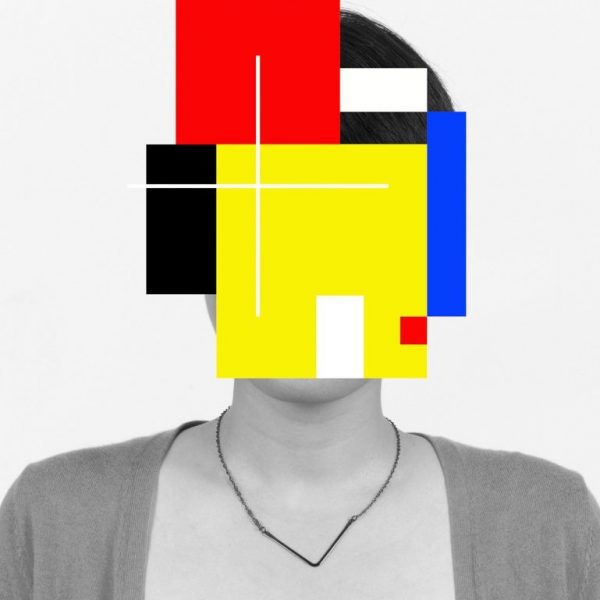

Celia Hempton,Aldo and Jesi, Albania, 16th August 2014,2014

ART.ZIP: There are many Internet artists in the show based their work upon the Internet, but you physicalise them to digital print, to attached photographs on the wall. Can you speak a bit more about this engagement between the physical and the virtual?

OK: I think that it is a key concern historically for artists who work with media, and especially who emerged after the advent of the World Wide Web. For example, there has always been a historical tension between representing browser-based work in the gallery and how spatially it has to work differently.

There was a very critical concern that was always in the back of my mind, particularly because of my own experience working in institutions, commissioning and working with artists online. The thing that I tried to do was to really think about artists who were engaging in that specificity, for example, Petra Cortright’s paintings that are made by using a series of brush acquired from deviant arches of the ‘Photoshop canvases’. They are literally hundreds of layers of virtual paint, once you print the work, there is a very specific back and forth with the printer— she is really thinking about the very different texture effects in the digital image.

Likewise, with Jon Rafman who began this series of modernist 3D printed head. They start as digital series but the way they engage the technology—also thinking about the form and aesthetics as physical object—was very different. Also likewise Aleksandra Domanović’s hands pieces, which were based on an utopian potential of the prothesis, man and the machine, physically, these hands are referring back to those very specific Serbian scientist whose name is Rajko Tomović. They are based on his prosthesis, but each of them is layered with specificities. For instance, you see Alan’s apple as an evocation of Alan Turing.

When they are in a film, when they become protruding objects, those images become hermeneutic spatial effects for the viewer. They engage the sense in a very different way— and likewise in Amalia Ulman’s Instagram performance represented in photographs. I think it does something very different than simply following the performance, which is when you watch it online, whether you’re appreciating those examination of the female body. When you put them as object in a gallery, they become these almost fetish things, which speak very critically to the fact that she is drawing a very particular portrait of how these performative technologies create those very specific pressures on the body. So because the body is such an important part of the virtual space, the idea of materialising it in situ creates a very different kind of atmosphere and a very different type of relationship with the viewer. But also, I was even thinking about our visitors who don’t necessarily engage with those practices online, how these can be an entry point for them to start looking at those things online. So I think that those things are symbiotic as opposed to exclusive of each other.

ART.ZIP: 這次展覽中還展出了很多以互聯網為創作媒介的網絡藝術家,你將他們的作品通過物質化的手段轉換成打印的圖片并置於展墻之上,你可以談談關於這種虛擬與物質概念之間的處理嗎?

OK: 我想從歷史的角度來說這是許多多媒體藝術家關心的關鍵問題,特別是那些互聯網興起後而出現的藝術家。比如,一直存在著一個歷史問題,就是如何處理基於瀏覽器展示的作品在畫廊空間中呈現效果的差異問題。

在我的腦海裡一直存在著這樣一個重要的議題,尤其是因為我本身就在機構裡通過網絡向藝術家徵集作品和溝通的體會。我嘗試著做的事情實際上是關於那些面對這些問題而作出反應的藝術家,比如佩拉特·科特萊特(Petra Cortright)的畫作就使用了基於“Photoshop界面”上的非常規筆刷。當你打印這件作品時,實際上有數百個虛擬的圖層,打印機需要特定地來回打印——她確實想了很多關於數碼圖像的不同質感的效果。

同樣的,瓊·拉夫曼(Jon Rafman)也是這麼考慮製作3D打印現代頭像系列作品的。他們都從數碼系列創造入手,不過他們應用科技的方式非常不同尋常——始終考慮實體的形式和美感。亞利珊卓·多瑪諾維奇(Aleksandra Domanović)的作品也是一樣,是基於烏托邦式的机械假肢創作的,其理論可追溯至一位塞爾維亞科學家拉伊科·托末維奇(Rajko Tomović)。 這些手都是基於他的機械假肢創作的,但是各個作品又各有特指。比如,當你看到阿蘭的蘋果時就會想起阿蘭·圖靈(Alan Turing)。

當圖像出現在電影中,當它們成為顯而易見的物品,這些圖像有助於觀眾們對作品的整體理解。這種虛擬內容與感官的互動是非常不同的體驗,就如亞美莉雅·埃爾曼(Amalia Ulman)在Instagram的行為表演以攝影的方式呈現。觀看她的這件作品不僅僅是“關注”其賬號和更新那麼單純,你對女性肉體的態度都成為了她作品範疇的一個部分。當你把這樣的作品放置於展廳之中,它們就像成了戀物癖患者的收藏品,藝術家用這樣的手段惟妙惟肖地刻畫和批判了當下社交媒體和科技給我們身體帶來的壓力。正因為身體是那個虛擬空間的重要組成部分,把它在特定場域內物質化的想法構造出了一種不同的氛圍,以及一種不同的與觀眾之間的關係。不過,同樣的,我甚至也考慮過那些並不參與此類網絡活動的觀眾,怎樣把這些作品作為他們開始去關注網絡事物的切入點。所以我認為這些事物是具有象徵意義的,它們並不是相互孤立存在的。

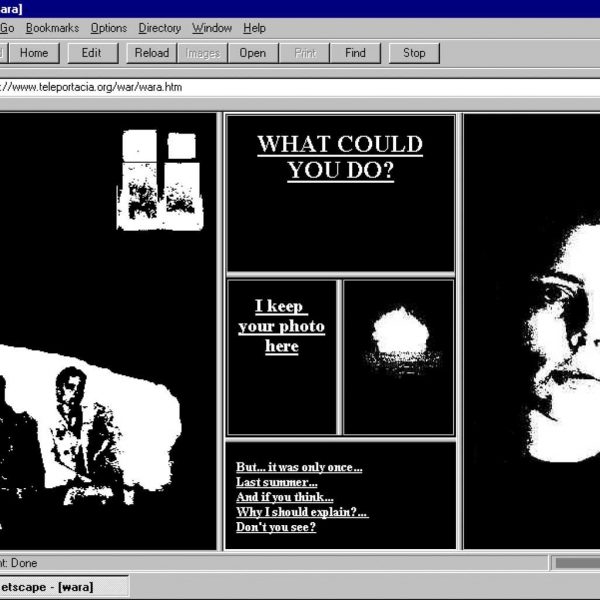

Amalia Ulman, Excellences & Perfections (Instagram Update, 18th June 2014), 2015

ART.ZIP: To see those works in the same context, new questions arise. For instance, around the browser-based, you were taking about discourses around online curating and democratisation of art; but all the sudden you see them with the basis of social media and somehow those questions of democratisation of the art online are requestioned in a way. Do you see social media then as a way of extending the democratisation of online based art?

OK: I certainly feel that social media to a degree allows the conversation around art to emerge. I am into mind about the potential of these spaces about civic democratic spaces because of the option of that cooperation or governments. Indeed I am very interested in artists’ critique about that, for instance, Trevor Paglen in the show of Autonomy Cube, the hybrotic cables that were done by the National Security Agency.

But what I love about these spaces is that, for example, all the browser-based pieces shown on the second floor which were co-curated with Rhizome: those are all the pieces that would continue to exist online. We very specifically thought about how we will present them in the gallery. For example, Jan Robert Leegte’s piece is a browser-based artwork which is very aesthetic and formal, is presented in the gallery in three different web browsers, to illustrate how the technology shifts and evolves, and makes the actual formal makeup of these works become different. And then, in a way, the exhibition has a potential to show an archaeology of the media and material of ‘what can happen online’, which, for me, is a very interesting thing which is also about exploring this utopic narrative of democracy. Because sometimes it isn’t very democratic when technology shifts so quickly and becomes so obsolete that to maintaining the work that you produce becomes a huge burden. Another interest of mine is this idea of obsolescence and conservation. How these more historic figures have really struggled because of the financial pressures of maintaining these works into the 21st century.

So what I hope the show does is to create the conversation about these practices as I see this is a debate show to bring it, really a constellation of hyperlinks together, this kind of crisscross and dovetails. Sometimes it contradict each other but is also part of the beauty of the Internet that the context by which to engage is a varied kind of fluid and would allow this kind of morphous discourses to emerge as well.

ART.ZIP: 在同樣的場景中看這些作品,新的問題也會產生。比如,正如你所談到的基於瀏覽器的關於在線策展和藝術民主化的問題,當你從社交媒體的角度去看待這些問題時,不知不覺之中在線藝術民主化的問題又從另一個角度被再次質疑。你是否認為社交媒體可以作為網絡藝術民主化的一種延伸?

OK: 我很明确地感受到了社交媒体在一定程度给予了艺术讨论的空间。我對存在于網絡的虛擬空間非常感興趣,這種公民性的民主空間內產生的合作和組織形式讓我著迷。而且,我對藝術家對此所作出的批判和思考也很感興趣,比如在特雷弗·佩格蘭(Trevor Paglen)《自主立法(Autonomy Cube)》的作品中的集線器就是由國家安全局製作的。

讓我著迷于虛擬空間的原因還有很多,比如在二層展廳中我和根莖藝術機構(Rhizome)合作策劃的那些網絡瀏覽器作品,它們將在展覽結束后繼續存在於虛擬網絡之中。我們對所有作品在展廳中呈現的方式都進行了深思熟慮。比如,簡·羅伯特·里格特(Jan Robert Leegte)的作品是一件基於網絡瀏覽器的藝術作品 ,非常唯美,也很有形式感,我們在展廳中使用了三個不同的瀏覽器來呈現,據此展示了科技是如何轉變和發展的,於是作品的最終形態也因此而有所不同。於是,展覽提供了一個可能性來展示媒體和物質領域的發展歷程,以及探討“在網絡上到底可以發生什麼?”這樣的問題,對我來說,這些都是特別有意思的事情,這讓我們能夠去思考和探索這種烏托邦式的民主敘事形式。因為網絡空間不總是民主的,由於科技發展的日新月異以及軟硬件的淘汰越來越快,在網絡空間保存這些藝術作品往往成為了一種負擔。這也是另一個我對網絡虛擬空間比較感興趣的地方:關於對淘汰和保存概念的探討,如何讓這些具有歷史意義的作品能夠在財務壓力之下持續地被保存至今。

因此,我希望這次展覽可以引發對於這些實踐問題的討論,正如我把它設置成一場討論式的展覽那樣,希望它能夠切實地成為超鏈接互相交匯的星雲圖。有時它們互相矛盾,但是這恰好是互聯網的絕妙之處,在這一語境中充滿了各種各樣的交融,也產生了各種形態的討論。

Installation shoot. Jan Robert Leegte, Scrollbar composition web

ART.ZIP: What was the most difficult thing when you put together these very different traditions?

OK: For me one of the problems is that some exhibitions can be very didactic. And also I want to shift this idea that exhibition has to engage multiple media and multiple functions—being didactic overlooks boundary and overly explanatory. There was a very sophisticated spatial negotiation with my colleagues here to think about how the works were formally and spatially dialogue with each other to create a sense of connection. So as you walk around this space you are confronted by various different bodies—from James Bridle to Olaf Breuning to Katja Novitskova and Aleksandra Domanović, then you move deeper into the texture of the first one and you start to see painting that has been deconstructed, and basically modernist tradition is explored and examined. And as you go deeper you start to see the history of image making deconstructed— completed through Constant Dullaart, Evan Roth, Oliver Laric, and so really it was about those layers of experience and layers of connection as opposed to thinking and bearing hermetically of trying to think about the over-didactic. But I think that maybe it is an exhibition more specifically tied to the technology itself and I try to give it a specific look only into technology. Also I am interested in the concepts of forms and the aesthetics that emerge from these things and how artists push and stretch things against their original intention or purpose to create ideas. So in a sense I think doing an exhibition can achieve that from the configuration of it.

ART.ZIP: 當你把這些不同的傳統匯聚在一起時,最大的困難是什麼?

OK: 我覺得不少展覽都太過注重說教,我希望改變這種現狀,展覽不一定非要採用多媒體的形式,也不需要太多的功能性,說教式的展覽往往給出了太多的解釋,設置了過多的邊界。我和同事們進行了非常複雜的空間劃分,我們思考了如何讓每件作品能夠在形式上和空間上產生交流,由此構建一種互相關聯的感官體驗。於是,在展覽空間中漫步時你將面對不同的體驗——從詹姆士·布萊德爾(James Bridle)到奧拉夫·布魯寧(Olaf Breuning)再到卡提亞·諾威茨科娃( Katja Novitskova)和亞利珊卓·多瑪諾維奇(Aleksandra Domanović),然後你就會更深入探尋第一件作品的肌理,於是你會開始發現繪畫被解構了,然後現代主義的傳統也被拿出來探索和檢驗。

隨著你的進一步觀看,你會發現圖像製作的歷史也被解構了——通過康斯坦特·杜拉爾(Constant Dullaart)、伊凡·羅斯(Evan Roth)、奧列弗·拉瑞克(Oliver Laric)來完成這一過程,因此這其實是關於不同層次的體驗和關聯,這與說教式的構想和過於說教式地關於超辯證的構思是相左的。不過我想也許是因為這是一場與科技本身緊密相關的展覽,而我試著對科技的關注給予一種特殊的呈現。同時我也很關注從這些事物中產生的形式和美學概念,以及藝術家是如何超越他們原來的設想達成創新的。因此從某種意義上來說,我想一場展覽是可以通過自我配置來實現的。