Dr. Baoping Li, ART.ZIP

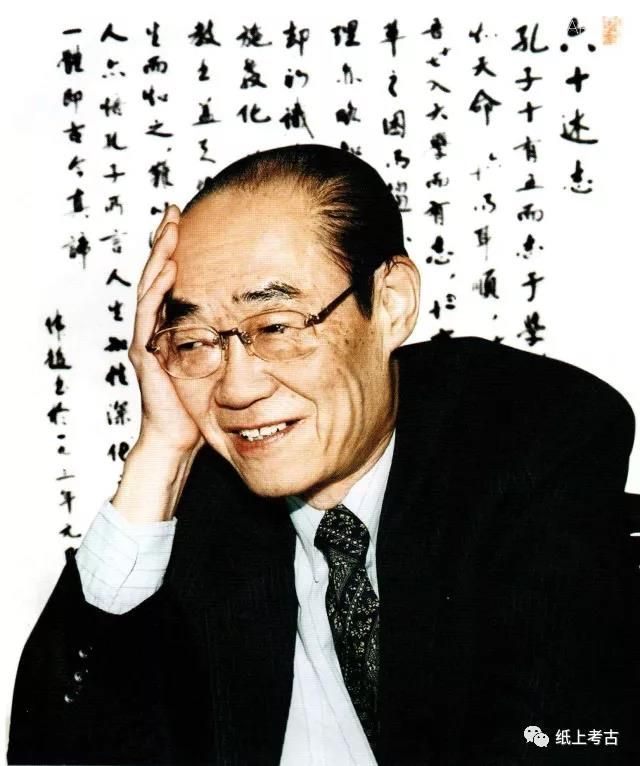

The Nanhai I is a Chinese merchant ship that sank in the South China Sea (Nanhai) while carrying a cargo of ceramics and other goods for export during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). The shipwreck was found in the waters of Guangdong in 1987, the year when an underwater archaeology section was formed by the China History Museum (now the China National Museum) with the support of its late director Yu Weichao (1933–2003) (fig. 1), a renowned scholar. Nanhai I was discovered when Maritime Exploration and Recovery Ltd. of the UK worked with China on the 1772 Rimsberg shipwreck of the Dutch East India Company.

fig.1 Yu Weichao, late director of China History Museum and founder of underwater archaeology in China

In 1989, a team of Chinese and Japanese experts performed the first survey of the Nanhai I site and roughly situated the shipwreck. Between 2001-2004, with funding from the Chinese government and various diving circles in Hong Kong (Chen Laifa, et al.), Chinese maritime archaeologists carried out seven underwater surveys, precisely locating the shipwreck and retrieving many objects. The wreck lay in about 25 metres (82 ft) of water and was covered in mud, which were perfect conditions for preservation. Both the ship and its contents are in exceptionally good condition compared with other shipwrecks. The ship is about 23.8 metres long, 9.6 metres wide.

Ongoing excavation of the Nanhai I shipwreck in Guangdong Maritime Silk Road Museum, Yangjiang

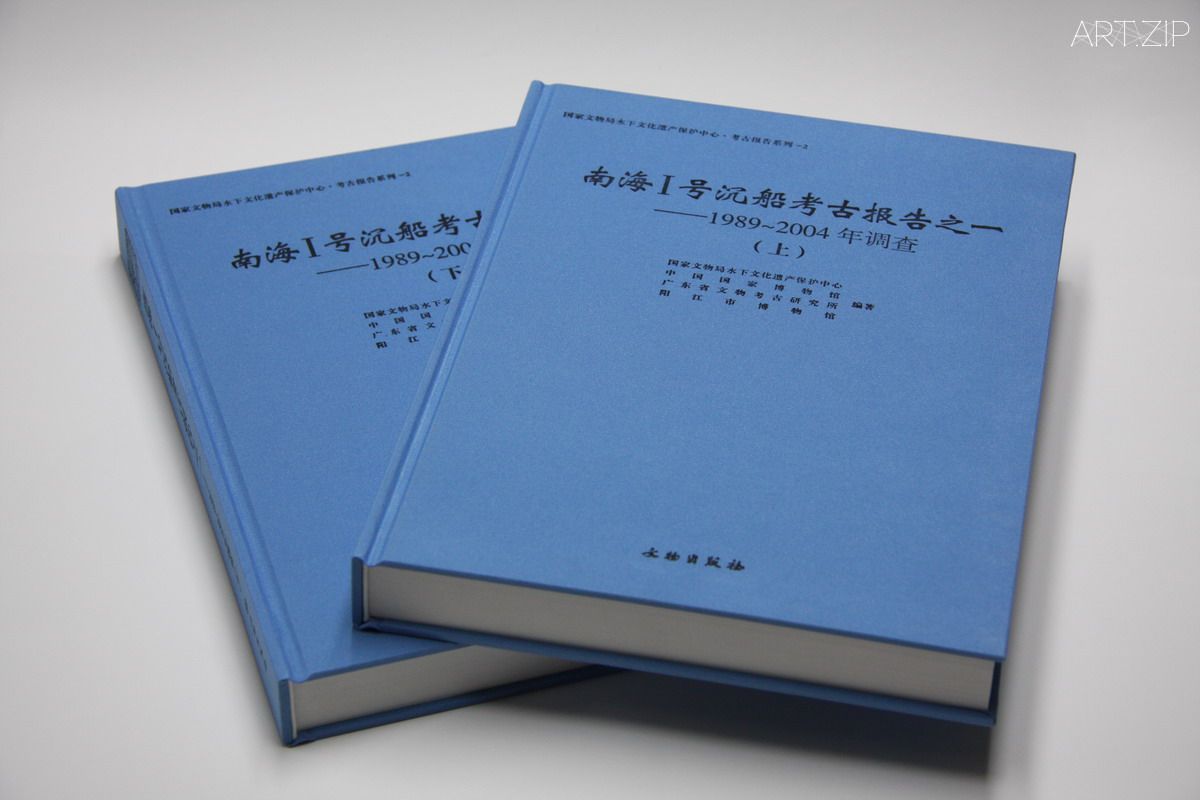

In 2007, the salvage team built a massive steel cage around the shipwreck. They then raised the shipwreck and the surrounding silt inside the cage and moved all to a new purpose-built museum in Yangjiang for well-controlled ongoing preservation and excavations (fig. 2). In Yangjiang in November 2017, an international symposium on the Nanhai I wreck was organised to commemorate the 30th anniversary of its finding, jointly by the Underwater Cultural Heritage Preservation Centre of State Administration of Cultural Heritage, Guangdong Province Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, and Guangdong Maritime Silk Road Museum in Yangjiang. In the meantime a two-volume book was published jointly by the various institutes involved (fig. 3), entitled Archaeological Report on Nanhai I Shipwreck Series 1: Surveys of 1989–2004. Following this, Archaeological Report on Nanhai I Shipwreck Series 1I: Surveys of 2014–2015 was published in 2018, also in two volumes.

fig.3 Archaeological Report on Nanhai I Shipwreck Series 1: Surveys of 1989–2004

About 21,000 pieces/sets of objects and 2,600 less complete specimens have been found to date from the ongoing work of this shipwreck, which include both trade goods and personal items, and sustenance for the crew and merchants (and/or passengers) aboard. As with many shipwrecks, most of these are ceramics, but there are also hundreds of gold and silver objects, such as Chinese gold leaves and silver ingots, which were used as currency, and exotic ornaments from other regions (fig. 4).

- fig.4 Gold plated bracelet, belt, and gold ring

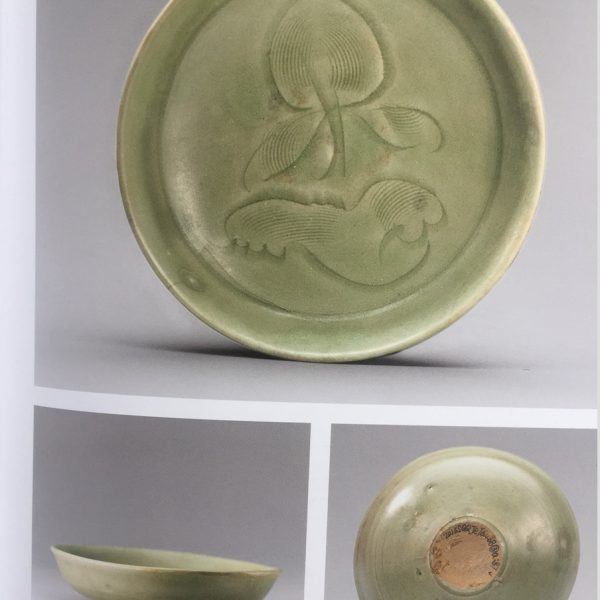

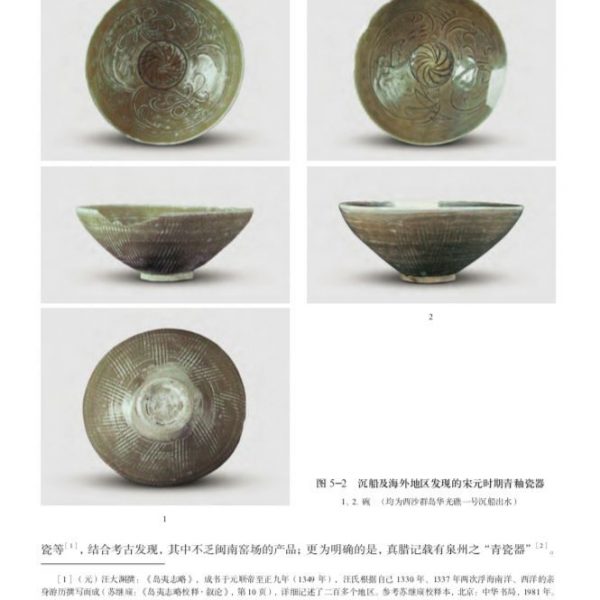

Also found were Chinese bronze, iron, lead, tin, bamboo, wood, lacquer and stone wares, including a stone seated figure of Guanyin (Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara or Goddess of Mercy), plus many animal and plant materials, such as grapes and pepper. Apart from these are some 17,000 coins spanning from the Han (206 BCE-220 CE) to the Southern Song dynasty which probably served as currency along the trade routes. Most of the coins are from the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127), and the latest found to date are from the Qiandao period (1165–1173), although for some time those from the Shaoxing period (1131–1162) were latest found on the shipwreck. Among the ceramics found are qingbai (bluish white) glazed porcelain from Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province, greenwares from Longquan in Zhejiang province, and ceramics of various glaze colours from kilns of Fujian province, such as Dehua and Cizhao (fig. 5).

- fig.5-1 Whiteware-from-Dehua-kilns-in-Fujian-1

- fig.5-2 Celadon from Longquan kilns in Zhejiang

It is believed that the ship may have set sail from Quanzhou in Fujian (or Guangzhou in Guangdong), and was bound for Southeast Asia or the Middle East, the precise destination has yet to be ascertained. As a unique merchant shipwreck salvaged with its entire content, the significance of this time capsule is hard to overstate. It also forms an interesting comparison with the British warship, the Mary Rose, that sank in 1545 during England’s war with France. She was salvaged in 1982 and is currently displayed as part of the Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth, England. We look forward to more discoveries from its ongoing work.

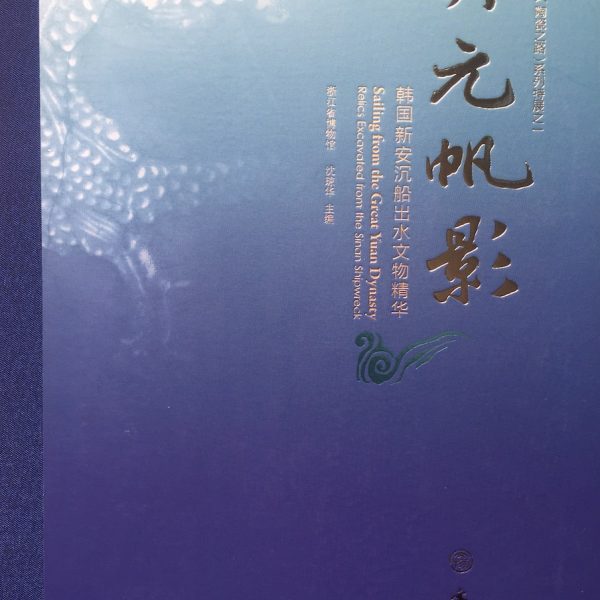

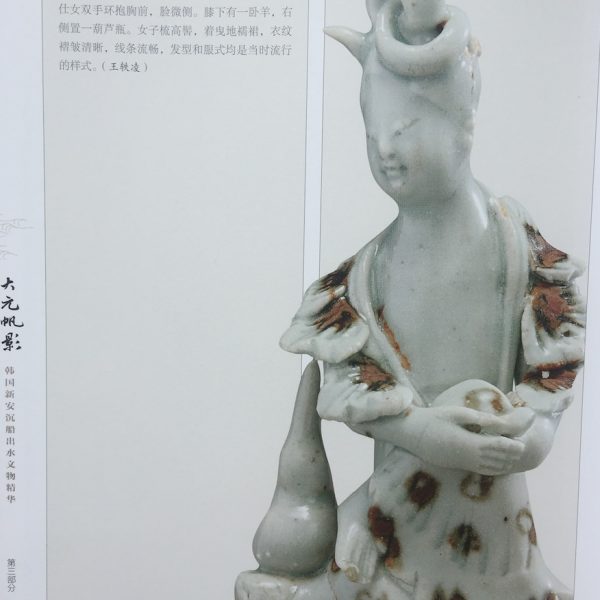

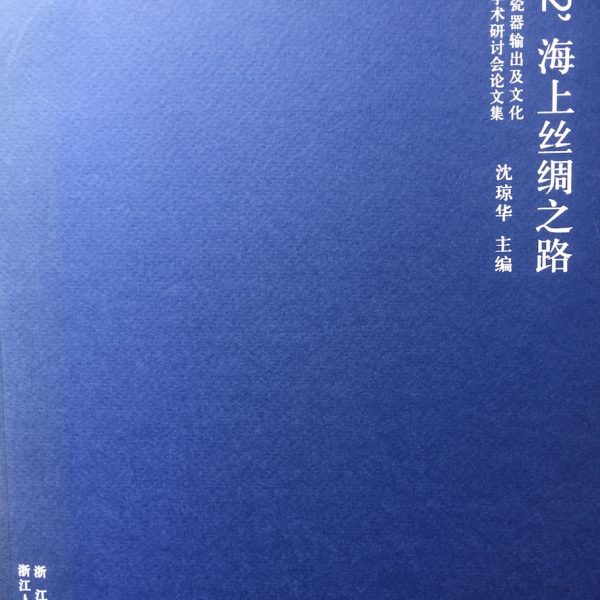

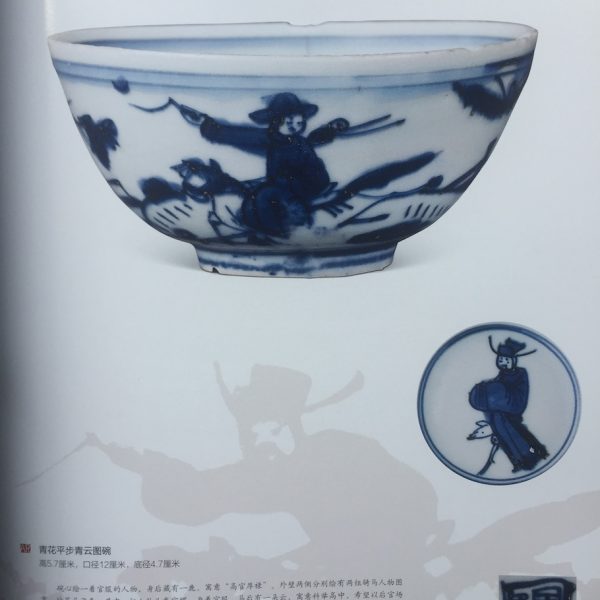

In view of the significance of shipwrecks and ceramcis for studying maritime trade of the human kind, it is also worthy to mention a few other important exhibitions and publications in recent years. In 2012 the Zhejiang Province Museum held an exhibition on the famous Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) Sin’an wreck of c. 1323 CE found in South Korea waters in 1976. Titled Sailing from the Great Yuan Dynasty: Relics Excavated from the Sin’an Shipwreck, the exhibition was accompanied with an international symposium on Chinese export ceramics. Both the exhibition catalogue and conference volume was edited by the curator of the Museum, Ms. Shen Qionghua (fig. 6).

- fig.6-1

- fig.6-2

- fig.6-3

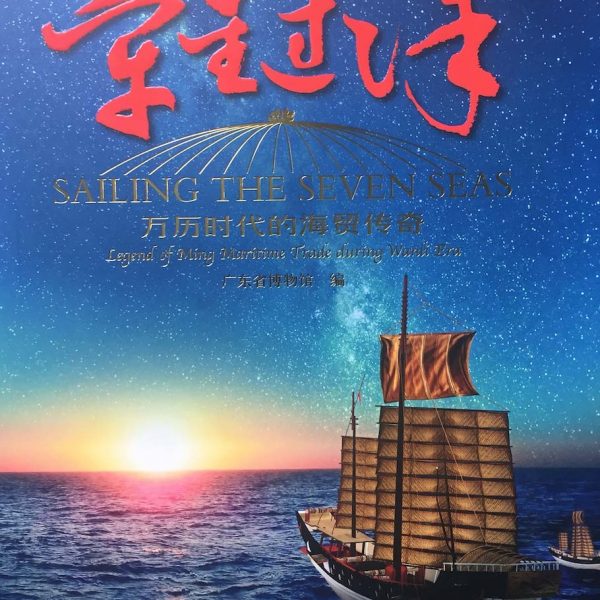

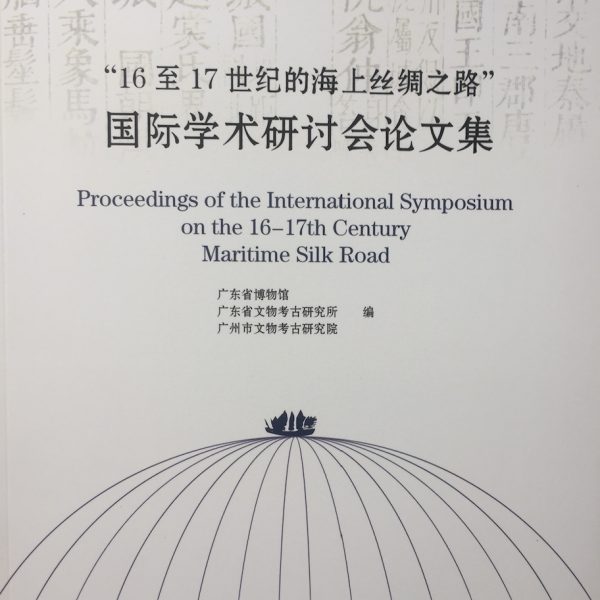

In 2015, the Guangdong Province Museum held an exhibition that centred around two shipwrecks of the Ming period (1368–1644), the Nan’ao I wreck found in Guangdong and the Wanli wreck found in Malaysia. Titled Sailing the Seven Seas: Legend of Ming Maritime Trade During Wanli Era, the exhibition was accompanied with a catalogue edited by Dr. Wei Jun, the director the Museum, as well as an international symposium on related subject which was published in 2016 (fig. 7).

- fig.7-1

- fig.7-2

- fig.7-3

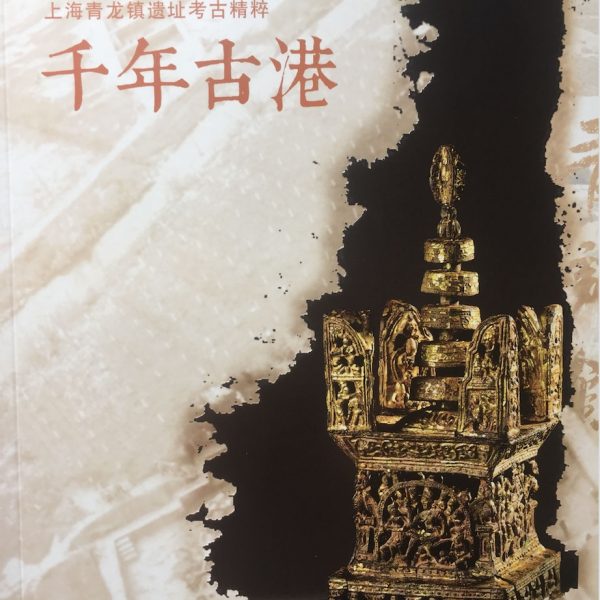

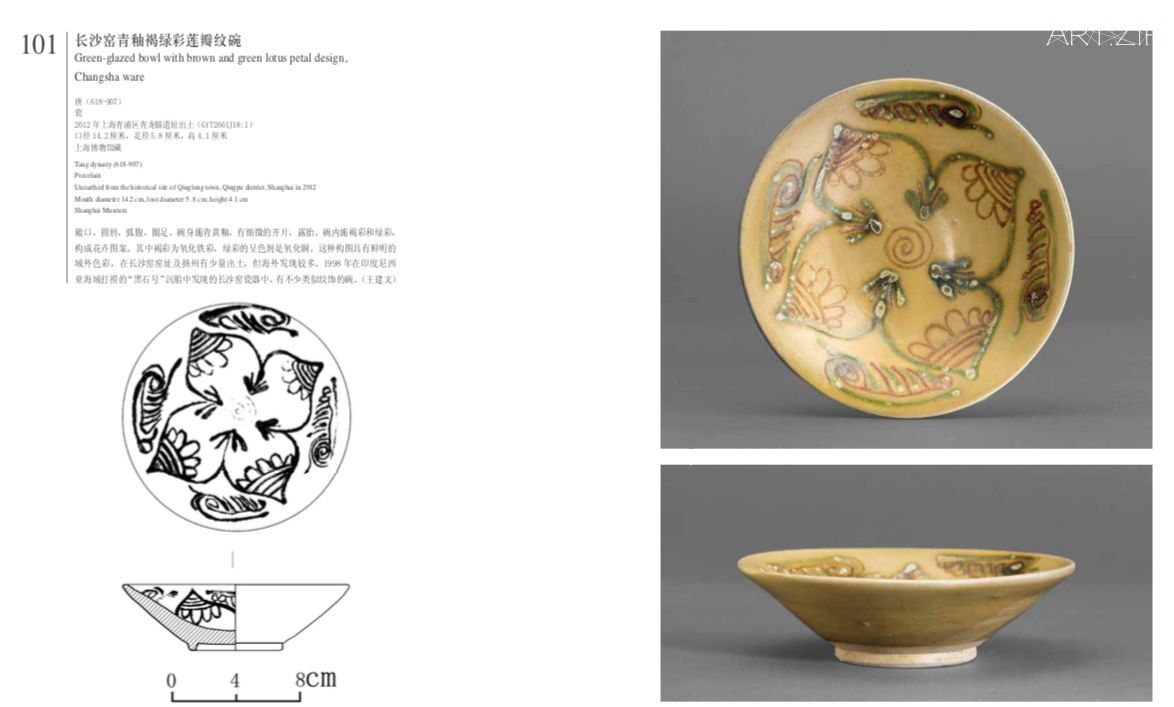

Also noteworthy is the archaeological excavation of an important port site in Qinglong town, Shanghai, which was ranked one of the Top Ten Chinese Archaeological Discoveries of 2016. In end of 2016 an exhibition on this site was held at the Shanghai Museum, curated by directors of the Museum, Yang Zhigang, Li Zhongmou and Chen Jie, with a catalogue published in 2017 (fig. 8).

- fig.8-1

- fig.8-2

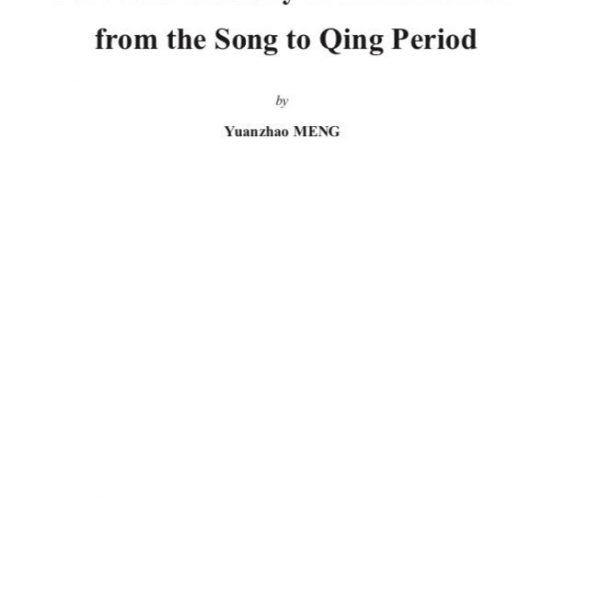

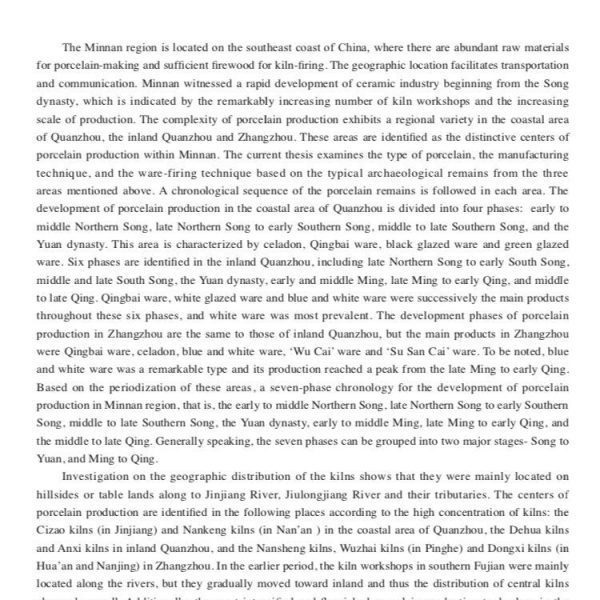

An important monograph on Chinese export ceramics from south Fujian province is also very noteworthy (fig. 9). The book as by Meng Yuanzhao from the Underwater Cultural Heritage Preservation Centre of State Administration of Cultural Heritage, based on his PhD thesis at the School of Archaeology and Museology, Peking University, under supervision of late ceramic archaeologist Prof. Quan Kuishan (1948-2012).

- fig.9-1

- fig.9-2

- fig.9-3